STORIES, POEMS, REVIEWS, ARTICLES Westerly a Quarterly Review•

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Journal of Biography and History: No

Contents Preface iii Malcolm Allbrook ARTICLES Chinese women in colonial New South Wales: From absence to presence 3 Kate Bagnall Heroines and their ‘moments of folly’: Reflections on writing the biography of a woman composer 21 Suzanne Robinson Building, celebrating, participating: A Macdougall mini-dynasty in Australia, with some thoughts on multigenerational biography 39 Pat Buckridge ‘Splendid opportunities’: Women traders in postwar Hong Kong and Australia, 1946–1949 63 Jackie Dickenson John Augustus Hux (1826–1864): A colonial goldfields reporter 79 Peter Crabb ‘I am proud of them all & we all have suffered’: World War I, the Australian War Memorial and a family in war and peace 103 Alexandra McKinnon By their words and their deeds, you shall know them: Writing live biographical subjects—A memoir 117 Nichola Garvey REVIEW ARTICLES Margy Burn, ‘Overwhelmed by the archive? Considering the biographies of Germaine Greer’ 139 Josh Black, ‘(Re)making history: Kevin Rudd’s approach to political autobiography and memoir’ 149 BOOK REVIEWS Kim Sterelny review of Billy Griffiths, Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia 163 Anne Pender review of Paul Genoni and Tanya Dalziell, Half the Perfect World: Writers, Dreamers and Drifters on Hydra, 1955–1964 167 Susan Priestley review of Eleanor Robin, Swanston: Merchant Statesman 173 Alexandra McKinnon review of Heather Sheard and Ruth Lee, Women to the Front: The Extraordinary Australian Women Doctors of the Great War 179 Christine Wallace review of Tom D. C. Roberts, Before Rupert: Keith Murdoch and the Birth of a Dynasty and Paul Strangio, Paul ‘t Hart and James Walter, The Pivot of Power: Australian Prime Ministers and Political Leadership, 1949–2016 185 Sophie Scott-Brown review of Georgina Arnott, The Unknown Judith Wright 191 Wilbert W. -

BBC ONE AUTUMN 2006 Designed by Jamie Currey Bbc One Autumn 2006.Qxd 17/7/06 13:05 Page 3

bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:03 Page 1 BBC ONE AUTUMN 2006 Designed by Jamie Currey bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:05 Page 3 BBC ONE CONTENTS AUTUMN P.01 DRAMA P. 19 FACTUAL 2006 P.31 COMEDY P.45 ENTERTAINMENT bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:06 Page 5 DRAMA AUTUMN 2006 1 2 bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:06 Page 7 JANE EYRE Ruth Wilson, as Jane Eyre, and Toby Stephens, as Edward Rochester, lead a stellar cast in a compelling new adaptation of Charlotte Brontë’s much-loved novel Jane Eyre. Orphaned at a young age, Jane is placed in the care of her wealthy aunt Mrs Reed, who neglects her in favour of her own three spoiled children. Jane is branded a liar, and Mrs Reed sends her to the grim and joyless Lowood School where she stays until she is 19. Determined to make the best of her life, Jane takes a position as a governess at Thornfield Hall, the home of the alluring and unpredictable Edward Rochester. It is here that Jane’s journey into the world, and as a woman, begins. Writer Sandy Welch (North And South, Magnificent Seven), producer Diederick Santer (Shakespeare Retold – Much Ado About Nothing) and director Susanna White (Bleak House) join forces to bring this ever-popular tale of passion, colour, madness and gothic horror to BBC One. Producer Diederick Santer says: “Sandy’s brand-new adaptation brings to life Jane’s inner world with beauty, humour and, at times, great sadness. We hope that her original take on the story will be enjoyed as much by long- term fans of the book as by those who have never read it.” The serial also stars Francesca Annis as Lady Ingram, Christina Cole as Blanche Ingram, Lorraine Ashbourne as Mrs Fairfax, Pam Ferris as Grace Poole and Tara Fitzgerald as Mrs Reed. -

AREAWIDE INSURANCE Country Music Classics Grissom Estate

The Monitor • Naples, Texas 75568-0039 • Thursday, April 15, 2021 • Page 5 #52 WANT AD DEADLINE MONDAY @ 11:11 A.M. CHARGES: 50¢ PER WORD LEGALS: 70¢ PER WORD $6.00 MINIMUM ADS PAID IN ADVANCE 903-897-2281 CONTRIBUTIONS & DO- NATIONS for the upkeep and DOGWOOD care of the Mt. Moriah Cem- TREE SALE etery at Omaha, will be ac- cepted and appreciated. Grissom $15 / $20 Make your donations at the City National Bank, in down- SHAW'S town Naples. Estate Auction NURSERY VOTE HELP WANTED 381 CR 1335 903-388-5278 We need volunteers to Mt. Pleasant, TX 75455 Highway 259 help with the Hands Ex- FOR AND ELECT South Of tended program. We need Saturday, April 17th @ 9:30am Highways 67 & 259 volunteers to help pick up Preview: Friday, April 16 - 12pm-6pm WILLIAM (TURTLE) POPE Intersection food in Mt. Pleasant 3 Please Note: Some items will be offered TO THE OMAHA times a week and in Tyler 50-3tc once a month. We need ONLINE as well for absentee bidding April 8th OMAHA volunteers to help unload, - April 16th - The Highest Bid will be deter- CITY COUNCIL weigh and put up food 3 mined during the Live Auction on Saturday, JOB OPPORTUNITY - Ser- times a week at the April 17th ON MAY 1, 2021 vice Tech for Pewitt CISD Naples center and we transportation department. need volunteers to help This property has been in the family for over ••••°°°°•••• Applicatons can be filled out with distributions during 100 years. It is a Super Nice place with all SERVED FOUR TERMS onine through the Pewitt the week and on the third types of items from Old (antiques) to New (www.pewittcisd.net) Saturday of the month. -

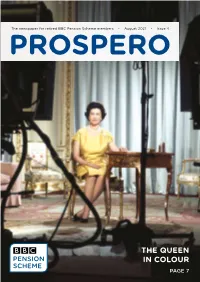

August 2021 • Issue 4 PROSPERO

The newspaper for retired BBC Pension Scheme members • August 2021 • Issue 4 PROSPERO THE QUEEN PENSION IN COLOUR SCHEME PAGE 7 | BACK AT THE BBC RICHARD SHARP, THE NEW BBC CHAIRMAN Richard Sharp was appointed Chairman of the BBC in February, replacing Sir David Clementi when he stepped down. s Chairman of the Board for the next four Richard has had a 40-year career in finance working years, Richard is responsible for upholding with a number of financial institutions. Most notably Aand protecting the independence of the BBC. he worked at JP Morgan and was for 23 years a He is responsible for ensuring that the BBC fulfils partner at Goldman Sachs. Subsequently Richard its mission to inform, educate and entertain and served for two terms on the Bank of England’s promotes its public purposes. The Chairman ensures Financial Policy Committee, charged with protecting that the Board’s decision-making is in the public the UK’s financial stability. Richard has served on the interest, informed by the best interests of the boards of public and private companies in the UK, audience and with appropriate regard to the impact Germany, Denmark and the United States. Wire DCMS/PA of decisions on the wider media market in the UK. Throughout his career Richard has supported and The fees for non-executive directors of the BBC Board The Board, under the Chairman, also must ensure held governance roles in a number of non-profit are set by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media that the BBC maintains the highest standards of organisations including, amongst others, the Royal and Sport. -

Download PDF ^ Articles on the Green Green Grass Episodes

SIRUYTXZZSNO # Book « Articles On The Green Green Grass Episodes, including: List Of The Green... A rticles On Th e Green Green Grass Episodes, including: List Of Th e Green Green Grass Episodes, One Flew Over Th e Cuckoo Clock, From Here To Paternity, A Rocky Start, Th e Country W ife (th e Green Filesize: 2.62 MB Reviews Unquestionably, this is the greatest operate by any article writer. I could comprehended everything out of this written e ebook. Your way of life span will be transform as soon as you total reading this book. (Andy Erdman) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 3Z2W2OLABY54 // PDF # Articles On The Green Green Grass Episodes, including: List Of The Green... ARTICLES ON THE GREEN GREEN GRASS EPISODES, INCLUDING: LIST OF THE GREEN GREEN GRASS EPISODES, ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO CLOCK, FROM HERE TO PATERNITY, A ROCKY START, THE COUNTRY WIFE (THE GREEN To get Articles On The Green Green Grass Episodes, including: List Of The Green Green Grass Episodes, One Flew Over The Cuckoo Clock, From Here To Paternity, A Rocky Start, The Country Wife (the Green eBook, make sure you refer to the link beneath and download the document or have access to additional information that are have conjunction with ARTICLES ON THE GREEN GREEN GRASS EPISODES, INCLUDING: LIST OF THE GREEN GREEN GRASS EPISODES, ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO CLOCK, FROM HERE TO PATERNITY, A ROCKY START, THE COUNTRY WIFE (THE GREEN ebook. Hephaestus Books, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. PRINT ON DEMAND Book; New; Publication Year 2016; Not Signed; Fast Shipping from the UK. -

Blasphemy and Sacrilege in a Multicultural Society

Negotiating the Sacred Blasphemy and Sacrilege in a Multicultural Society Negotiating the Sacred Blasphemy and Sacrilege in a Multicultural Society ELIZABETH BURns COLEMAN AND KEVIN WHITE (EDITORS) Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Negotiating the sacred : blasphemy and sacrilege in a multicultural society. ISBN 1 920942 47 5. 1. Religion and sociology. 2. Offenses against religion. 3. Blasphemy. 4. Sacrilege. I. Coleman, Elizabeth Burns, 1961- . II. White, Kevin. 306.6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Indexed by John Owen. Cover design by Teresa Prowse. Art work by Elizabeth Burns Coleman. This edition © 2006 ANU E Press Table of Contents Contributors vii Acknowledgements xi Chapter 1. Elizabeth Burns Coleman and Kevin White, Negotiating the sacred in multicultural societies 1 Section I. Religion, Sacrilege and Blasphemy in Australia Chapter 2. Suzanne Rutland, Negotiating religious dialogue: A response to the recent increase of anti-Semitism in Australia 17 Chapter 3. Helen Pringle, Are we capable of offending God? Taking blasphemy seriously 31 Chapter 4. Veronica Brady, A flaw in the nation-building process: Negotiating the sacred in our multicultural society 43 Chapter 5. Kuranda Seyit, The paradox of Islam and the challenges of modernity 51 Section II. Sacrilege and the Sacred Chapter 6. Elizabeth Burns Coleman and Kevin White, Stretching the sacred 65 Chapter 7. -

Whiteness and Masculinity in the Works of Three Australian Writers - Thomas Keneally, Colin Thiele, and Patrick White

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2010 Black and White on Black: Whiteness and Masculinity in the Works of Three Australian Writers - Thomas Keneally, Colin Thiele, and Patrick White. Matthew sI rael Byrge East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons Recommended Citation Byrge, Matthew Israel, "Black and White on Black: Whiteness and Masculinity in the Works of Three Australian Writers - Thomas Keneally, Colin Thiele, and Patrick White." (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1717. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1717 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Black and White on Black: Whiteness and Masculinity in the Works of Three Australian Writers—Thomas Keneally, Colin Thiele, and Patrick White ________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of English East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Masters of Arts in English ________________________ by Matthew Israel Byrge May 2010 ________________________ Dr. Donald Ray Johnson, Director Dr. Phyllis Ann Thompson Dr. Karen Ruth Kornweibel Dr. Katherine Weiss Keywords: Aborigine(s), Australia, whiteness, masculinity, race studies, post-colonialism ABSTRACT Black and White on Black: Whiteness and Masculinity in the Works of Three Australian Writers— Thomas Keneally, Colin Thiele, and Patrick White by Matthew Israel Byrge White depictions of Aborigines in literature have generally been culturally biased. -

“THE GREEN, GREEN GRASS of HOME” Based on Genesis 2:1-9 Clan of Every Race, Has at One Notice the Wording Here

“THE GREEN, GREEN GRASS OF HOME” Based on Genesis 2:1-9 clan of every race, has at one Notice the wording here. God Tom Jones wrote the words, time contemplated their planted a garden in the east, in ‘It's good to touch the green, beginnings, and written down, as Eden. So was the garden, Eden, green grass of home.” Now I think best they understood, the creation or was there a special part of the he was referring to heaven, but I of life. The classic version of garden in the eastern section? suppose we could use the same Genesis 1 probably comes to your Something to ruminate about over lines to consider the state of mind first. lunch. But here is the interesting affairs in regards to our earth. In the beginning God created part for me: Truth is, you don’t hear too much the heavens and the earth…And these days about the ‘green, God said, “Let there be light,” and The Lord God made all kinds green grass of home’, but more there was light.” (v1,3). of trees grow out of the ground— about the green of envy and the By the end of the creation, all trees that were pleasing to the green of greed when it comes to living creatures had been made, eye and good for food. In the using and mis-using our earth. and humankind to enjoy it. middle of the garden were the Then of course, there is the tree of life and the tree of the heated battle of opinions right In Genesis 2, a very similar knowledge of good and evil. -

An Historical Analysis of the Contribution of Two Women's

They did what they were asked to do: An historical analysis of the contribution of two women’s religious institutes within the educational and social development of the city of Ballarat, with particular reference to the period 1950-1980. Submitted by Heather O’Connor, T.P.T.C, B. Arts, M.Ed Studies. A thesis submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of PhD. School of Arts and Social Sciences (NSW) Faculty of Arts and Sciences Australian Catholic University November, 2010 Statement of sources This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics/Safety Committees. i ABSTRACT This thesis covers the period 1950-1980, chosen for the significance of two major events which affected the apostolic lives of the women religious under study: the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), and the progressive introduction of state aid to Catholic schools, culminating in the policies of the Whitlam government (1972-1975) which entrenched bi- partisan political commitment to funding non-government schools. It also represents the period during which governments of all persuasions became more involved in the operations of non-government agencies, which directly impacted on services provided by the churches and the women religious under study, not least by imposing strict conditions of accountability for funding. -

Loreto Federation Australia Compressed-Compressed

Federation of the Loreto Ex-Students Associations Summary of Federations 1 - 25, 1955 - 2005 A Summary of the first 25 Federations collated by Regina (Jennifer) Cameron IBVM Photographs collated by Josephine Jeffery IBVM Printed 2008. CONTENTS Foreward page 3 Loreto Federation in Australia page 4 A Brief History of Loreto Federation Australia page 6 1st Federation, 1955 Melbourne page 7 2nd Federation, 1957 Adelaide page 11 3rd Federation, 1959 Sydney page 17 4th Federation, 1961 Brisbane page 20 5th Federation, 1963 Ballarat page 22 6th Federation, 1965 Perth page 25 7th Federation, 1967 Melbourne page 30 8th Federation, 1969 Adelaide page 32 9th Federation, 1971 Sydney page 36 10th Federation, 1973 Brisbane page 39 11th Federation, 1975 Ballarat page 40 12th Federation, 1977 Perth page 46 13th Federation, 1979 Melbourne page 48 14th Federation, 1981 Adelaide page 52 15th Federation, 1983 Sydney page 55 16th Federation, 1985 Brisbane page 58 17th Federation, 1987 Ballarat page 60 18th Federation, 1989 Adelaide page 63 19th Federation, 1991 Melbourne page 66 20th Federation, 1992 Sydney page 70 21st Federation, 1994 Brisbane page 76 22nd Federation, 1997 Perth page 79 23rd Federation, 2000 Ballarat page 84 24th Federation, 2003 Adelaide page 90 25th Federation, 2005 Melbourne page 96 Venues, Themes, Presidents page 109 Summary page 146 Personal Viewpoints page 150 Federation Constitution page 151 1 MOTHER GONZAGA’S IDEA FOR A LORETO FEDERATION During the twenty years after Mother Gonzaga Barry founded the first Loreto school in Australia at Mary’s Mount in Ballarat, further foundations were made in Portland, Melbourne, Sydney and Perth. -

The Casual Vacancy by J.K. Rowling

Also by J.K. Rowling Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (in Latin) Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (in Welsh, Ancient Greek and Irish) Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them Quidditch Through the Ages The Tales of Beedle the Bard Copyright First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Little, Brown and Hachette Digital Copyright © J.K. Rowling 2012 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ‘Umbrella’: Written by Terius Nash, Christopher ‘Tricky’ Stewart, Shawn Carter and Thaddis Harrell © 2007 by 2082 Music Publishing (ASCAP)/Songs of Peer, Ltd. (ASCAP)/March Ninth Music Publishing (ASCAP)/Carter Boys Music (ASCAP)/EMI Music Publishing Ltd (PRS)/Sony/ATV Music Publishing (PRS). -

VERITY December 2015 from the PRINCIPAL

VERITYDECEMBER 2015 STMARYS.UNIMELB.EDU.AU 1 INSIDE THIS ISSUE 03 A Word from the Principal 04 From the Editor 05 Open Day 06 Christmas In July 08 Dean’s Dinner Speech 12 News from the Academic Centre 13 O2 week 14 The College Ball 16 News from the St Mary’s College Student Club 16 Student Club Dinner 17 2015 Quidditch 17 Faculty Dinner 18 Valete 22 Valete Dinner Speech given by Sr Elizabeth Hepburn ibvm Moral Imagination and Discernment 24 Culture Report 26 College Musical 28 St Mary’s Market PFA 30 Sports Report 34 Alumni News 37 Alumni Reunions 2 VERITY December 2015 FROM THE PRINCIPAL The end of the 2015 academic year arrived quickly and the college’s corridors are eerily quiet and empty…. definitely not their natural state! DR DARCY MCCORMACK As I write this, the students are at home – Zhang and Ms Laura Brennan, President weekend of 12/13 March 2016 and I hope or further afield - and I am left wondering and Vice-president respectively of the that many of you will visit the college that where 2015 went! It seems so recently that student General Committee, who guided weekend to catch-up with old friends and I arrived in January 2015 to a construction me through the activities in the yearly cycle; see our greatly improved facilities; site and made a temporary office in a the knowledge that I have the support of • The college will welcome two outstanding student room - in that room interviewing the students has sustained me. In Semester academics as Scholars-in-residence: 42 applicants for admission before 2, we all benefited significantly from the Professor Anne Steinemann is Professor moving into the principal’s office on the presence of Ms Rachel Lechmere in the of Engineering and Chair of Sustainable day immediately preceding ‘Arrival Day’.