Accounting for the Water Use by Wildlife in Botswana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8 Day Accomodated Safari -Journey Through Botswana

"JOURNEY THROUGH BOTSWANA” is an 8-Day fully accommodated "moBile" Safari that takes in all that ChoBe National Park, Khwai Private Reserve, Moremi Game Reserve and the Okavango Delta offers-from the outset exploring ChoBe River to the remarkaBle Game viewing... the 7 nights spent utilizing different lodges & luxury camps Based in this unique wilderness that Botswana showcases',will leave indeliBle memories of spectacular wildlife and evenings spent around a campfire under Billions of stars. This 8 Day accomodated safari overnights at permanent camps-offering something for guests who do not particularly want to "camp", But who like the idea of a moBile safari that offers an outstanding level of private guiding throughout. This safari can start in Maun and end in Kasane as well.... "JOURNEY THROUGH BOTSWANA" 8 DAY FULLY ACCOMODATED SAFARI from $4995pp RACK TOUR CODE :WDJB DEPARTURE POINT IS KASANE AIRPORT OR KAZUNGULA BORDER ON THE SOUTHBOUND TRIP AND MAUN AIRPORT ON THE NORTHBOUND TRIP. GUESTS NEED TO BE AT THE MEETING POINTS BY 12H30 on day 1, unlEss comIng off IntErnatIonal flIghts whIch gEnErally land at about 13h00. Day 01 CHOBE RIVER ChobE rIvEr In thE northEast sErvEs as thE prImary watEr sourcE for thE IanImals and draws many watEr- lovIng bIrd spEcIEs...hIppos, crocodIlE Impala, sablE, lEchwE, gIraffE, zEbra, baboons, bushbuck, monkEys and puku antElopE. ThIs ExclusIvE boat cruIsE takEs placE In thE Early aftEroon. ChobE NatIonal Park Is thE sEcond largEst NatIonal Park In Botswana.WIth swEEpIng vIEws ovEr thE ChobE RIvEr, JackalbErry ChobE's stunnIng publIc arEas arE thE pErfEct sEttIng to rElax and unwInd .TakE to thE watErs of thE ChobE RIvEr on a 3-hour sunsEt cruIsE In pontoon boats. -

Self Drive Safari Planning Guide

SELF-DRIVE SAFARI PLANNING GUIDE bushlore.com So you are planning a self drive-safari in Africa? It is the perfect holiday option for travellers that enjoy freedom and flexibility! A self-drive safari in Southern Africa is one of the most popular travel options for visitors planning to explore Africa. But you need to plan every aspect carefully. This guide is here to help you make the right decisions. Let’s start planning! 1. HOW MANY IN YOUR GROUP? The number of people traveling together influences quite a few aspects of your trip. You should choose the 4x4 vehicle based on your group size, as well as the accommodation and campsites where you plan to stay along the way. TWO FOUR FAMILY MORE+ + bushlore.com PLAN YOUR SAFARI TO SUIT YOUR GROUP SIZE 4x4 Rental vehicles are set up according to the number of people travelling. But it also depends on your specific requirements. A family will have a different setup to a couple. It also influences the places you plan to visit. A large group will require more space for the vehicles, and a group of four using two vehicles can possibly make use of one site in some camps. If there are special requests, you need to take that into consideration. You might want to make use of a ground tent as some of your travel partners do not want to sleep in a rooftop tent. If two intrepid friends travel together, they might want to each have their own tent. This is where expert advice comes into play. -

Sanctuary Chief's Camp

CHIEF’S CAMP SANCTUARY CHIEF’S CAMP BOTSWANA The ultimate luxury safari experience SANCTUARY CHIEF’S CAMP Welcome to the former royal hunting reserve of Chief Moremi, in the heart of the Okavango Delta. Wildlife and wilderness are as abundant as action and adrenaline and refinement and relaxation at this remarkable remodelled luxury camp. Personal service, an extraordinary setting, exceptional viewing and enthusiastic expert guides are the hallmarks of a Sanctuary Retreats experience – here at Sanctuary Chief’s Camp we promise a unique attention to detail and strong environmental and philanthropic credentials to ensure the ultimate luxury safari experience. Intimate and exclusive, Sanctuary Retreats properties are always set in outstanding natural landscapes. Here in this game reserve, thanks to soul-stirring perspectives from the private pavilions, the lounge deck and your dinner tables, you won’t ever miss the thrill of a viewing. As well as ensuring a distinct sense of Botswanan place, every encounter and activity feels authentic, thanks to the camp having been reimagined in keeping with local traditions and cultures – which is how we believe responsible tourism should be. Sanctuary Chief’s Camp’s sophisticated accommodation with natural hues and materials that complement the charismatic scenery and the first-class dining and wines, regularly earns rankings among the world’s top safari destinations from arbiters such as Condé Nast Traveler and Travel & Leisure. AT A GLANCE • Simple contemporary design, • Award-winning dining stylish interiors • Commitment to sustainability and • Unrivalled views, on safari and philanthropic projects from camp • Rich in references to the Camp’s history • Personalised, intuitive service and royal heritage • Expert guides, insider knowledge Bathroom with a view LUXURIOUS PAVILIONS Spacious and breezy, at 460 ft2 (140m2) the 10 stylish bush pavilions are some of the region’s largest places to spend the night. -

Ramsar Information Sheet

Ramsar Information Sheet Text copy-typed from the original document. 1. Date this sheet was completed: 20.11.1996 2. Country: Botswana 3. Name of wetland: The Okavango Delta System 4. Geographical co-ordinates: The Okavango Delta System lies between Longitudes 21 degrees 45 minutes East and 23 degrees 53 minutes East; and Latitudes 18 degrees 15 minutes South and 20 degrees 45 minutes South. It includes the Okavango River, commonly referred to as the Pan handle; the entire Okavango Delta; Lake Ngami; and parts of the Kwando and Linyanti River systems that fall west of the western boundary of the Chobe National Park. The entire area is as depicted on the attached map. 5. Altitude: Generally between 930 metres and 1000 metres above sea level. 6. Area: Approximately 68 640 km² (6 864 000 hectares) 7. Overview Three main features characterise the region, the Okavango, the Kwando and Linyanti river system connected to the Okavango Delta through the Selinda spillway and the intervening and surrounding dryland areas. These features are located within the Okavango rift, a geological structure subject to tectonis control and infilled with Kahalari Group sediments, principally sand, up to 300 metres thick. The Delta is the most important of the above named features. It is an inland delta in a semi arid region in which inflow fluctuations result in large fluctuations in flooded area (10,000 - 16,000 km²), which is comprised of permanent swamp, seasonal swamp and intermittently flooded areas. Similar flooding takes place in the Kwando/Linyanti river system. This leads to high seasonal concentrations of birdlife and wildlife, giving the area a very high tourism potential. -

Luxury Botswana Safari Tours and Botswana Safaris

BOTSWANA Luxury Botswana Safari Tours Botswana Safaris Over the past 15 years, Botswana has emerged as one of the most exclusive and authentic safari destinations in southern Africa. Bolstered by a stable government committed to conservation of its precious wildlife areas, Botswana boasts a wide array of well regulated and preserved ecosystems making it the ideal country to plan your Luxury African safari tours. Two thirds of the land consists of arid Kalahari desert unsuitable for agriculture making for a unique African wildlife safari experience. Out of this desert landscape arises an incredible example of nature’s unpredictability: the Okavango Delta. Okavango Delta is a must for Luxury Botswana Safari Tours, fans out across Botswana’s north- western corner and creates a paradise of islands and lagoons teeming with birds and wildlife making it the ideal destination for a Botswana safari tour. In the northeast, the famous Chobe National Park supports great concentrations of Elephant and Buffalo making the ideal place for boating and land-based safaris. In the southeast the Tuli Block, supports some of Botswana’s only commercial farming along with magnificent game reserves and offers unique horseback riding safaris as well as cycling safaris. Linyanti Game Reserve lies to the northeast of the Okavango Delta famed for its huge herds of elephant. The bulk of the concession is comprised of different Mopane woodland associations, with a strip of riparian forest and floodplain. Looking for a unique and completely different Botswana safari experience? Visit Makgadikgadi Salt Pans to enjoy nature drives on the pans, quad biking adventures, visits to the regions gigantic Baobab trees, and up close encounters with real colonies of wild meerkats. -

Deeper Botswana DAY-BY-DAY ITINERARY ©Beverly Joubert/Duba Plains Camp/Great Plains Conservation Plains Camp/Great Plains ©Beverly Joubert/Duba Safari in Style

888.658.7102 [email protected] www.deeperafrica.com Deeper Botswana DAY-BY-DAY ITINERARY ©Beverly Joubert/Duba Plains Camp/Great Plains Conservation Plains Camp/Great Plains ©Beverly Joubert/Duba Safari in style With its winding channels, azure lagoons, papyrus reeds and patchwork of savannas, the world’s largest inland delta is a paradise for wildlife. The majestic Okavango Delta is home to a high density of species and water-adapted animal behaviors unique to Botswana. Explore areas well-known for impressive guiding and once in a lifetime wildlife viewing. Witness lions hunt buffalo. Embark on water-based safaris. View wild dogs. Stay in the heart of Chief’s Island in the Delta—considered one of the best places to view wildlife on the planet—and relax in the best accommodations that Botswana has to offer. Welcome to Deeper Africa ©Chief’s Retreats Camp/Sanctuary Wildlife encounters, at once spontaneous and beyond imagination, result from our in-depth Dknowledge of useasonal wildlifem migrations and patterns.elang Our guides possess a lifetime of African lore and all the skills of a master tracker. It’s being in the perfect place at the perfect time. As a worldwide team with vast experience, we provide you with exceptional personal service. We attend to every detail. We help you learn about Africa’s important conservation issues. Arrive in Africa fully prepared and ready to explore. We believe that local African communities must benefit and prosper from the conservation and enjoyment of Africa’s wildlife. They ensure the future. Your dollars protect wildlife and wild lands, as well as support and nurture local small businesses that in turn support our safari business. -

So You Have Always Wanted To… Walk in the Footsteps of Elephants and Bushmen

So you have always wanted to… Walk in the footsteps of Elephants and Bushmen Selinda Explorers Camp, Selinda Reserve Day 3-5 Day 1-3 Duba Explorers Camp, Okavango Delta MOREMI GAME RESERVE BOTSWANA Maun Day 5-7 Jack’s Camp, Makgadikgadi Pans National Park SUGGESTED ITINERARY OVERVIEW ACCOMModation Destination NIGHTS BASIS ROOM TYPE Duba Explorers Camp Okavango Delta, Botswana 2 FB Tent Selinda Explorers Camp Selinda Reserve, Botswana 2 FB Tent Makgadikgadi Pans National Park, Jack’s Camp 2 FB Room Botswana DAYS 1 - 3 Duba Explorers, The Okavango Delta THE OKAVANGO DELTA Lying in the middle of the largest expanse of sand on earth the Okavango Delta is one of Africa’s most amazing, sensitive and complex environments. Unique as the largest of the world’s few inland deltas, the placid waters and lush indigenous forests offer a safe haven for innumerable bird and wildlife species. The renowned Duba Explorers Camp sits in the heart of classic Okavango Delta habitat. A matrix of palm-dotted islands, flood plains and woodland, the 77,000 hectare private concession typifies the region’s unique landscape. Many consider Duba Plains to be the Okavango’s Maasai Mara because of the sheer volume of wildlife. Duba Plains prides itself on its extraordinary wildlife experiences with reliable sightings of lion, buffalo, red lechwe, blue wildebeest, greater kudu and tsessebe. Elephant and hippo trudge through the swamps and leopard, and some nocturnal species, can be sighted as well. Birds abound, and the area is a birdwatcher’s paradise. Okavango ‘specials’ include the rare wattled crane, Pel’s Fishing owl, white-backed night heron and marsh owl. -

Family Safari: Moremi Game "Botswana, the Pinnacle of Safari Reserve, Okavango Delta, Destinations

T H E A F R I C A H U B B Y S M A L L W O R L D M A R K E T I N G B O T S W A N A T r u s t e d i n s i d e r k n o w l e d g e f r o m h a n d p i c k e d e x p e r t s S A M P L E I T I N E R A R Y # 1 I N P A R T N E R S H I P W I T H K E R & D O W N E Y B O T S W A N A Family Safari: Moremi Game "Botswana, the pinnacle of safari Reserve, Okavango Delta, destinations. The pristine wilderness Central Kalahari Reserve areas offer the ultimate in exclusive safari experiences. Rich in diversity, each 7 nights unique ecosystem offers a variety of birds, plants and wildlife." - Fran Hird, Ker & Downey Botswana W W W . S M A L L W O R L D M A R K E T I N G . C O . U K / T H E A F R I C A H U B I T I N E R A R Y W H O ? Families with children aged 7 or older O V E R V I E W (no maximum age!) H I G H L I G H T S 2 nights | Okuti 3 nights | Young Explorers Learn how to track game at Young Explorers Camp 2 nights | Dinaka Experience the practices and traditions of the San Bushmen in the Central Kalahari Families will spend 7 nights exploring and Diverse range of water and land based activities learning the game rich and diverse regions throughout the itinerary of the Okavango Delta and Central Kalahari regions of Botswana. -

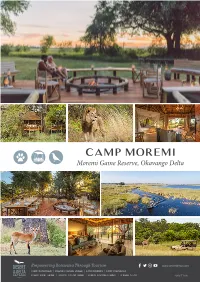

CAMP MOREMI Moremi Game Reserve, Okavango Delta

CAMP MOREMI Moremi Game Reserve, Okavango Delta Empowering Botswana Through Tourism CAMP OKAVANGO I XUGANA ISLAND LODGE I CAMP MOREMI I CAMP XAKANAXA CHOBE GAME LODGE I SAVUTE SAFARI LODGE I CHOBE SAVANNA LODGE I LEROO LA TAU AUGUST 2020 M10 B8 ZAMBIA T1 ANGOLA B8 Chobe Savanna Lodge Kasane C49 Livingstone Victoria ZAMBEZI NAMIBIA Chobe Game Lodge NATIONAL Falls Zambezi Region PARK Chobe River KASANE FOREST A33 RESERVE Kwando River CHOBE CHOBE FOREST RESERVE NATIONAL KWANDO PARK BOTSWANA Linyanti River ZIMBABWE Savute Safari Lodge LINYANTI SELINDA Savuti Channel OKAVANGO SAVUTI Savuti Marsh DELTA KHWAI Xugana Island Lodge Camp Xakanaxa Camp Okavango Camp Xakanaxa Khwai River Camp Moremi CHIEF’S ISLAND MOREMI GAME A35 RESERVE OKAVANGO DELTA Camp Moremi NXAI PAN NATIONAL BOTSWANA PARK Maun Boteti River A3 A3 Xakanaxa Lagoon LOCATION MAP Leroo La Tau MOREMI GAME RESERVE Lake Ngami MAKGADIKGADI PANS NATIONAL PARK Makgadikgadi Pan For the classic African safari experience, look no further than Camp Moremi in Botswana’s world-renowned Moremi Game Reserve. Camp Moremi is situated on the edge of the Xakanaxa Lagoon in an area well known for its spectacular game-viewing opportunities. Xakanaxa Lagoon Pool Deck Loo with a View Fire Pit Deck Boma Deck 3 2 1 Dining Area Family 6 5 4 Room 7 Bar Lounge Library Public 10 Bathroom 11 8 Curio 9 Shop Reception & Office 12 CAMP LAYOUT Arrival Empowering Botswana Through Tourism THE CAMP FACILITIES 11 Luxury Tents & 1 Family Tent (2 en-suite bedrooms) ROOMS accommodating a maximum of 24 guests. PILOT/GUIDE 1 x Pilot/Guide Tent (not same standard as guest rooms). -

Elephant Social Dynamics, Spatial Ecology and Human Elephant Conflict in the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans and Kalahari Ecosystems

Elephant Social Dynamics, Spatial Ecology and Human Elephant Conflict in the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans and Kalahari Ecosystems August 2009 Submitted to: Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Botswana Funded by: The San Diego Zoo and Elephants Without Borders Michael Chase Elephants Without Borders Po Box 682 Kasane Botswana Tel/Fax: ++267 6250202 Email: [email protected] PROJECT NARRATIVE Background Conservation management plans for wildlife species require accurate and reliable longitudinal information about population size, distribution, demography, reproductive rate and habitat use. However, obtaining detailed data is often hampered due to financial and time constraints imposed on local governments and scientists. Our fundamental aim in this segment of our elephant ecology study in the Kavango Zambezi TFCA is to augment the elephant conservation efforts of the Botswana Government by conducting research on the ecology of elephants in the Makgadikgadi and Kalahari ecosystems to identify factors regulating the spatiotemporal distribution and habitat use of elephants. Our ultimate goal is to share this information with appropriate authorities, communities and the scientific community, in order to mitigate Human Elephant Conflict (HEC) while simultaneously promoting the conservation of African elephants and their natural habitats in Botswana. Our study is unique and timely in that it monitors elephant range patterns in and out of national parks, across international boundaries and in habitats ranging from nearly desert to wetland/riverine environments. No other study has sought to conserve a “flagship” species by incorporating such a large and varied ecosystem. By adopting the most rigorous scientific methods and state-of- the- art techniques to derive estimates of elephant population size and distribution, as well as movement patterns across the region, we will greatly improve our understanding of the dynamic forces regulating elephant life histories, and their interactions with people thereby make significant contributions towards elephant conservation in Botswana. -

Traditional Exploration : Botswana

P a g e | 1 Traditional Exploration : Botswana P a g e | 2 P a g e | 3 Traditional Exploration: Botswana Maun - Okavango Delta - Khwai Community Area - Savuti - Chobe National Park - Chobe River Front 12 Days / 11 Nights Date of Issue: 19 January 2020 Click here to view your Digital Itinerary P a g e | 4 Introduction Accommodation Type Destination Basis Duration Thamalakane River Lodge Maun B&B 1 Night Okavango Still Mobile Boating Safaris FI 4 Nights → Chao camp Okavango Delta FI 2 Nights → Noraga Lagoon camp Okavango Delta FI 2 Nights Khwai River View Khwai Community Area FI 2 Nights Pride of Africa - Luxury Mobile Camp - Central FI 3 Nights Chobe Chobe Princesses FI 1 Night Key B&B: Bed and Breakfast FI: Fully Inclusive - Bed, All Meals, Fees and Activities P a g e | 5 Day 1: Thamalakane River Lodge, Maun Botswana Situated in the southern reaches of Africa, Botswana is renowned for its pristine wilderness areas characterised by deep lagoons, wetlands, lush palms, rugged hills and desert plains scattered with scrubland. The country’s primary tourist drawcard is undoubtedly the vast red expanse of the Kalahari Desert and its remarkably beautiful Okavango Delta, the largest inland delta in the world. These natural wonders provide a tranquil haven for an abundance of African wildlife to thrive. Other highlights include the impressive Makgadikgadi Salt Pans, where visitors are privy to massive zebra migrations during the flood season; the Savuti plains, which host large prides of lions; and the Tsodilo Hills, where 4500 rock paintings form a unique record of human settlement over many millennia. -

Desert, Delta and Falls (Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe) - 52 Days

Desert, Delta and Falls (Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe) - 52 Days Major Destinations Gaborone - Khama Rhino Sanctuary - Khutse Game Reserve - Central Kalahari Game Reserve - Makgadikgadi Pans National Park - Ntwetwe Pan - Sowa Pan - Nxai Pan National Park - Maun - Okavango Delta - Moremi Game Reserve - Savute - Linyanti - Chobe National Park - Livingstone - Victoria Falls - Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park - Zambezi National Park Tour Highlights and Activities In terms of the incredible diversity of wildlife and uniquely contrasting landscapes, this is one of my favourite trips and includes four of the most precious natural jewels in all of Africa, the Kalahari Desert, the Okavango Delta, Chobe National Park and the mighty Victoria Falls. It is difficult to imagine that the arid, pristine wilderness of the Kalahari and the lush, fertile waterways of the Okavango Delta can exist within less than 100km of each other, but we will experience both extremes during this trip, as well as huge concentrations of wildlife at Chobe National Park, one of the largest protected areas on the continent. The magical Cessna flight over the Okavango and the thrilling open microlight flight above Victoria Falls, are two of the more spectacular highlights of this unforgettable journey, but our adventure will produce a host of memories as we savour peaceful Makoro safaris through the myriad channels of the Okavango and a sunset cruise on the remarkably beautiful Zambezi. Other enthralling activities will include canoe trips among hippos and crocodiles, rewarding horseback safaris and the opportunity to swim just a few metres from the very edge of the immensely powerful 108m cascade of Victoria Falls.