Exporting the Nordic Children's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Histories in Health Research ~

Personal Histories in Health Research ~ Edited by Adam Oliver ISBN: 1 905030 11 8 Personal Histories in Health collection © The Nuffield Trust 2005 ‘Ploughing a furrow in ethics’ © Raanan Gillon and The Nuffield Trust 2005 Published by The Nuffield Trust 59 New Cavendish Street London WC1 7LP telephone 020 7631 8450 fax 020 7613 8451 email: [email protected] website: www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk charity number 209201 designed and printed by Q3 Digital Litho telephone 01509 213 456 website: www.Q3group.co.uk Contents 1 Healthy Lives: reflecting on the reflections Adam Oliver 3 2 Health inequalities: from science to policy David Blane 15 3 In sickness and in health: working in medical sociology Mike Bury 29 4 Random assignments: my route into health policy: a post-hoc rationalisation Anna Coote 47 5 Last Season’s fruit John Grimley Evans 65 6 Ploughing a furrow in ethics Raanan Gillon 85 7 The Jungle: an explorer’s experiences of health services research Walter W Holland 101 8 Confessions of a graduate nurse Alison Kitson 121 9 Confessions of an accidental policy analyst, or why I am not a health service researcher Rudolf Klein 139 10 Seeking somewhere to stop Jennie Popay 155 11 Political ideals and personal encounters Albert Weale 173 12 Discovering the QALY, or how Rachel Rosser changed my life Alan Williams 191 13 Health policy, management and gardening Robert Maxwell 207 About the authors About the authors vii David Blane is Professor of Medical Sociology at Imperial College London. He trained in medicine and sociology, and enjoys teaching medical sociology as an applied subject to large classes of trainee doctors, and as an academic discipline to smaller numbers of interested medical students. -

Personal Histories of the Second Wave of Feminism

Personal Histories of the Second Wave of Feminism summarised from interviews by Viv Honeybourne and Ilona Singer Volumes One and Two 1 Feminist Archive Oral History Project Foreword by the Oral History Project Workers Ilona Singer and Viv Honeybourne The Oral History Project has been a fantastic opportunity to explore feminist activism from the 1970's onwards from the unique perspectives of women who were involved. We each conducted ten in depth qualitative interviews which were recorded (the minidisks will be kept at the archive as vital pieces of history themselves) and written up as an oral history. We used the open-ended questions (listed as an appendix), so as to let the women speak for themselves and not to pre-suppose any particular type of answer. We tried to involve our interviewees as much as possible in every stage of the research process. Many interviewees chose to review and amend the final write-ups and we were happy to let them do this so that they could have control over how they wished to be represented. The use of a snowball sampling method and the fact that our interviewees were willing volunteers means that these histories (herstories) are not meant to be representative in a strictly scientific sense. Some women were more publicly active in the period than others, but all our of interviewees had important stories to tell and vital reflections on the period. The oral histories have been included in alphabetical order. They are of differing lengths because some women spoke for longer than others and we felt that to strive excessively to limit their words would be imposing an artificial limit on their account of their own lives . -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

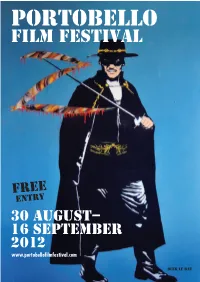

2012 Program

PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL FREE ENTRY 30 AUGUST– 16 SEPTEMBER 2012 www.portobellofilmfestival.com BLEK LE RAT Entry to all events if FREE and open to all over 18. ALTERNATIVE LONDON FILM FESTIVAL PORTOBELLO ALTERNATIVE PORTOBELLO POP UP CINEMA FILM FESTIVAL LONDON FILM INTERNATIONAL 3 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5TY 30 Aug – 16 Sept 2012 FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL POP UP CINEMA WESTBOURNE Thu 30 Aug Welcome to the 17th Portobello Film Act Of Memory – 30 Aug 3 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5TY STUDIOS GRAND OPENING Art at Festival. This year is non-stop new 30 August page 1 Portobello 242 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5JJ CEREMONY London and UK films at the Pop Up Grand Opening Ceremony POP UP CINEMA Film Festival with The Spirit Of Portobello, docoBANKSY, 31 August page 9 2012 and a feast of international movies at and a new film from Ricky Grover International Shorts Introduction Westbourne Studios courtyard and Pop Up 1 September 9 6:30pm Cinema throughout the Festival, plus 7–19th at 31 August 2 The Muse Gallery – see page 18 for details. Westbourne Studios. Just For You London German Night What We Call Cookies up and coming directors inc Greg Hall & Wayne G Saunders (Natalie Hobbs) 2 mins It’s all very well watching films on the 2 September 10 Exploring various British stereotypes held by internet but nothing beats the live 1 September 2 International Feature Films Americans played out by motifs that are iconicly Are You Local? 3 September 11 American. Comedy. independent frontline film experience. West London film makers Turkish & Canadian Showcase Big Society (Nick Scott) 7 mins 2 September 3 An officer in the British army questions what it means We look forward to welcoming film 4 September 11 to fight for your country when he sees his hometown London Calling: From The Westway To British & USA State Of The Movie Art rife with antisocial behaviour. -

The British Underground Press, 1965-1974: the London Provincial Relationship, and Representations of the Urban and the Rural

THE BRITISH UNDERGROUND PRESS, 1965-1974: THE LONDON PROVINCIAL RELATIONSHIP, AND REPRESENTATIONS OF THE URBAN AND THE RURAL. Rich�d Deakin r Presented as part of the requirement forthe award of the MA Degree in Cultural, Literary, andHistorical Studies within the Postgraduate Modular Scheme at Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education June 1999 11 DECLARATIONS This.Dissertation is the product of my own work and is. not the result of anything done in collaboration. I agreethat this. Dissertationmay be available forreference and photocopying,. at the discretion of the College. Richard Deakin 111 ABSTRACT Whateverperspective one takes, contradictions in the relationship between the capital and the provinces have always been evident to some extent, and the British undergroundpress of the late 1960s and early 1970s is no exception. The introductoryfirst chapter will definethe meaning of the term 'underground' in this context, and outline some of thesources used and the methodologies employed. Chapter Two will show how the British underground press developed froman alternative coterie of writers, poets, and artists - often sympathisers of the Campaign forNuclear Disarmament movement. It will also show how having developed from roots that were arguably provincial the undergroundadopted London as its base. The third chapter will take a more detailed look at the background of some London and provincial underground publications andwill attempt to see what extent the London undergroundpress portrayed the provinces, and vice-versa. In Chapter Four actual aspects of lifein urbanand rural settings, such as communes, squats, and pop festivals,will be examined in relation to the adoption of these lifestylesby the wider counterculture and how they were adapted to particular environments as part of an envisioned alternativesociety. -

The Jan Garbarek Group - Grab It! You Positively Having Fun with His Lads

Subscribe to Gonzo Weekly http://eepurl.com/r-VTD Subscribe to Gonzo Daily http://eepurl.com/OvPez Gonzo Facebook Group https://www.facebook.com/groups/287744711294595/ Gonzo Weekly on Twitter https://twitter.com/gonzoweekly Gonzo Multimedia (UK) http://www.gonzomultimedia.co.uk/ Gonzo Multimedia (USA) http://www.gonzomultimedia.com/ 3 Dear Friends, Welcome to another issue of this peculiar little magazine which never ceases to surprise me with But enough of the equine metaphors. I have never the twists and turns of where it goes. I would like to understood people’s fascination with domesticated say that I plan it that way, but I suspect that those of equids, and have always been far more drawn to you who read it wouldn’t believe me. My job as cold blooded things in rivers, streams and tanks. editor is far more akin to a rider doing his utmost best to quell the ambulatory excesses of a bucking The other day a mate of mine sent me one of those bronco, and doing his best not to be thrown off and things that I believe are called memes. It was a have all his bones smashed to sugar lumps, than to picture of a tranquil forest with the legend “If a Tree a well ordered rider doing some sort of dressage falls in a Forest and there is no-one to hear it, will trip with his well ordered steed. the Parliamentary Labour Party still claim that it is 4 THIS IS NOT AN EDITORIAL ABOUT POLITICS‼‼ THIS IS AN EDITORIAL ABOUT HUMAN NATURE‼‼ Jeremy Corbyn’s fault?” Now before we go any further. -

68: the Global Publishing Scandal of the Little Red Schoolbook

Exporting the Nordic children’s ’68: the global publishing scandal of The Little Red Schoolbook Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Open Access Heywood, S. and Strandgaard Jensen, H. (2018) Exporting the Nordic children’s ’68: the global publishing scandal of The Little Red Schoolbook. Barnboken Journal of Children's Literature Research, 41. ISSN 2000-4389 doi: https://doi.org/10.14811/clr.v41i0.332 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/79410/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Identification Number/DOI: https://doi.org/10.14811/clr.v41i0.332 <https://doi.org/10.14811/clr.v41i0.332> Publisher: Barnboken All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Sophie Heywood and Helle Strandgaard Jensen Exporting the Nordic Children’s ’68 The global publishing scandal of The Little Red Schoolbook Abstract: The Little Red Schoolbook (1969) was one of the most well- travelled media products for children from ’68 aimed at children, and it was certainly the most notorious. Over the course of a few years (1970–2) it was translated and published in Belgium, Finland, France, Great Britain, the Federal Republic of Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. -

Paulger DISSERTATION

Anglo-American Quality Press Narratives and Discourses of Sexual Revolution, 1958-1979 By Ross K. Paulger Registration No: 110221391 Supervisor: Dr Adrian Bingham Word Count: 66090 A dissertation submitted in part-fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History University of Sheffield March 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 1 Revolution as Concept ......................................................................... 2 Sexual Revolution(s) ........................................................................... 5 The Choice of Newspapers ................................................................ 16 Methodological Approaches .............................................................. 21 Types of Sources to be Analysed ...................................................... 28 Chapter Structure ............................................................................... 32 Chapter 1: FEMINISM AND WOMEN’S LIBERATION ......................... 35 Literature Review Concepts of Feminism(s) ........................................................ 35 History of Feminism(s) ........................................................... 39 Historiography of Feminism and Media ................................. 45 The Second Wave and Sexual Revolution .............................. 51 Primary Source Analysis .................................................................... 62 Analysis of British Primary Sources -

Too Much Feeling: S.E. Hinton's the Outsiders (1967), Conflicting

Children’s Literature in Education https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-020-09410-z ORIGINAL PAPER Too Much Feeling: S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders (1967), Conficting Emotions, Identity, and Socialization Lydia Wistisen1 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract This article argues that emotions are utilized for norm breaking, identity formation, and socialization in S.E. Hinton’s YA novel The Outsiders (1967). Drawing on the history of emotions studies, it investigates how emotional expressions are utilized to negotiate and contest given emotional norms on the one hand, and Young Adult literary conventions on the other. The point of departure is intersectional and focuses on the relationship between emotion, power, and socialization. In particular, the arti- cle considers how intersections of age, gender, and class relate to depictions of feel- ing and establishing of new emotional norms. The article shows that the feelings that the main character Pony expresses are part of a reiterative process of negotiation of power; they work as instruments for changing emotional norms connected to his age, class, and gender. Keywords S.E. Hinton · The Outsiders · Young Adult literature · Emotions · Masculinity · Post-war youth culture In S.E. Hinton’s pioneering YA novel, The Outsiders (1967), emotions are utilized for norm breaking, identity formation, and socialization. The novel revolves around a deadly confict between two youth gangs, the greasers and the Socs. The greas- ers are part of a youth subculture that was popularized in the 1950s and 1960s by predominantly working-class teenagers in the United States – the word “greaser” was applied to members because of their characteristic Elvis-Presley-inspired Lydia Wistisen is a researcher and lecturer at the Department for Culture and Aesthetics at Stockholm University. -

'...By Turns Absurd and Entrancing, If You're Prepared to Stay on the Bus, It Makes for an Exhilarating Ride

‘......by turns absurd and entrancing, if you’re prepared to stay on the bus, it makes for an exhilarating ride......’ The current popularity of the ukulele is such that it’s overtaking the recorder as an instrument taught in primary schools - though the question remains: what’s going to catch on next? Nose-flutes? Zithers? Musical saws? Maybe it’s because the learning process of stringed instruments is much more logical than those that require blowing. One day when I was about sixteen, my father - an auctioneer - brought home an oboe that hadn’t reached its reserve price. During the hours I spent attempting vainly to get to grips with it, no matter how many holes I covered, it usually emitted the same note - if any note at all - and the unpredictable harmonics jarred my teeth. Since then, all woodwind players have been worthy of my unconditional admiration. The first one I ever knew personally was John Harries, who I met in 1972 when I answered his advertisement on a college notice board for anyone interested in forming a group. Those interested had to convene at a given time in the common room of his girlfriend’s hall of residence. He held the door ajar for a motley bunch that included me with my worn-out six- string, Alan Barwise yet without his drum kit, an all-fingers-going acoustic guitarist, a girl with a Paul Simon songbook - and a bass player sans amplifier. I shall draw a veil over the subsequent proceedings - except to say that John was the only person to come out of it with any credit, principally by an instantly accepted respect for his instinctive command of the woodwind family by means that I suspect even he didn't fully understand. -

1 Children of the Revolution? the Hippy Counter-Culture, the Idea of Childhood and the Case of Schoolkids Oz David Buckingham T

Children of the revolution? The hippy counter-culture, the idea of childhood and the case of Schoolkids Oz David Buckingham This essay is part of a larger project, Growing Up Modern: Childhood, Youth and Popular Culture Since 1945. More information about the project, and illustrated versions of all the essays can be found at: https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/. On June 23rd 1971, a momentous trial began at London’s Old Bailey, the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales. In the dock were three young men, Richard Neville, Jim Anderson and Felix Dennis, the editors of Oz, an ‘underground’ magazine. They faced charges relating to issue 28 of the magazine, published in May of the previous year as Schoolkids Oz. They were accused of producing an obscene publication and sending it through the mail, for which the maximum penalties were three years and one year respectively; and, more broadly, of ‘conspiring… to produce a magazine containing divers lewd, indecent and sexually perverted articles, cartoons, drawings and illustrations with intent thereby to debauch and corrupt the morals of young children and young persons within the Realm and to arouse and implant in their minds lustful and perverted desires…’ – an archaic and rarely used charge for which the maximum penalty was life imprisonment, at the discretion of the judge. The Oz Trial was the longest-ever obscenity trial in British legal history, lasting nearly six weeks. Both at the time and subsequently, it assumed almost mythological proportions. Yet while the trial focused in great detail on the parts of Schoolkids Oz that were deemed obscene, relatively little attention was paid – either at the time or afterwards – to the publication as a whole. -

FILM FESTIVAL 1–18 Sept 2011 People’S Free State of Portobello Free Entry

FREE PORTOBELLO ENTRY FILM FESTIVAL 1–18 Sept 2011 www.portobellofilmfestival.com People’s Free State of Portobello Free entry. Front-line films. Street art. Good times. PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL POP UP CINEMA WESTBOURNE 1–18 Sept 2011 3 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5TY STUDIOS 1 September page 1 242 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5JJ Welcome to the 16th free Portobello Grand Opening Festival. This year we are focussing on featuring Ebony Road 5 September page10 Film Makers Convention Delegate 2 September 2 new London films and European Introduction and live interactive debate with Golborne Variations & local films Cinema at the Portobello Pop Up. The People Speak 3 September 2 Video Café & BYO 10 We are expanding the Video Cafe to 4 Animation Station nights in the Westbourne Studios 6 September 12 4 September 3 Video Café & BYO Europe In Meltdown Cinema which also plays host to the 7 September 14 London Film Makers Convention. A new 6 September 3 Video Café & BYO London Film Feast 1 development is the inclusion of website 8 September 16 featuring Jack Falls addresses for most films, so if you Video Café & BYO Weekend Family Film Shows 4 13 September 17 can’t make the festival you can choose 4 FREE features for kids London Film Makers Convention to watch it online. 7 September 5 with Film London Microwave directors London Film Feast 2 14 September 17 featuring Ultimate Survivor London Film Makers Convention 8 September 5 with Latimer Films & Alan Fountain London Film Feast 3 15 September 17 featuring Bikipela Bagrap London Film Makers Convention 9 September 6 with