Brickmaking on and Near the Bell Farm”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

Saskatchewan 2015

seescenic SaSkatchewan 2015 get ready for fun Music festivals - heap on Spa serenity - the art of Scenic drives and forest the talent | P. 4 relaxation | P. 12 jewels | P. 34 TOuRism areas SaSkatoon what’s inside 08 | Local treasures, openly shared mooSe JaW 16 | Surprisingly unexpected central 20 | Remarkable places to discover NORTH 28 | Always more to explore REGINA 36 | There’s a lot to love SOUTh 40 | A destination for every imagination EVENTs 48 | 2015 Saskatchewan calendar 4 28 34 36 Publisher: Shaun Jessome Advertising director: Kelly Berg MArketing MAnAger: Jack Phipps music Festivals scenic drives and Art director: Michelle Houlden Heap on the talent for forest jewels Layout designer: Shelley Wichmann Production suPervisor: Robert Magnell 2015 | 4 Narrow Hills | 34 freelAnce And editoriAl content: spa serenity Golfing Cheryl Krett, Jesse Green, Amy Stewart-Nunn, The art of relaxation. | 12 Alison Barton, Candis Kirkpatrick, Robin and Juniors, seniors, novices, Arlene Karpan duffers or even scratch golfers can find plenty of venues in Photography: Christalee Froese, Robin and Saskatchewan. | 46 Arlen Karpan, Candis Kirkpatrick, David Venne Photography, Cheryl Krett, JazzFest Regina, Tourism Saskatoon Tourism Saskatchewan Greg Huszar Photography Douglas E. Walker Eric Lindberg Paul Austring J. F. Bergeron/Enviro Fotos Rob Weitzel Graphic Productions Kevin Hogarth Larry Goodfellow Cheryl Chase Hans Gerard-Pfaff Manitou Springs Resort & Mineral Spa Advertising: 1-888-820-8555 Western Producer Co-op Sales: Neale Buettner Ext 4 Laurie Michalycia Ext 1 Catherine Wrennick Ext 3 Fax: 306-653-8750 See Scenic Saskatchewan is a supplement to ON THE COVER: Wakeboarding at Great Blue The Western Producer, PO Box 2500 Station Heron Provincial Park | Tourism saskaTchewan/GreG Main, 2310 Millar Ave. -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home. -

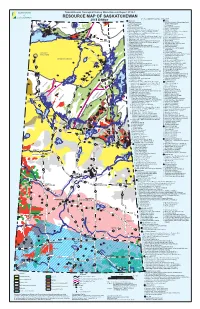

Mineral Resource Map of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan Geological Survey Miscellaneous Report 2018-1 RESOURCE MAP OF SASKATCHEWAN KEY TO NUMBERED MINERAL DEPOSITS† 2018 Edition # URANIUM # GOLD NOLAN # # 1. Laird Island prospect 1. Box mine (closed), Athona deposit and Tazin Lake 1 Scott 4 2. Nesbitt Lake prospect Frontier Adit prospect # 2 Lake 3. 2. ELA prospect TALTSON 1 # Arty Lake deposit 2# 4. Pitch-ore mine (closed) 3. Pine Channel prospects # #3 3 TRAIN ZEMLAK 1 7 6 # DODGE ENNADAI 5. Beta Gamma mine (closed) 4. Nirdac Creek prospect 5# # #2 4# # # 8 4# 6. Eldorado HAB mine (closed) and Baska prospect 5. Ithingo Lake deposit # # # 9 BEAVERLODGE 7. 6. Twin Zone and Wedge Lake deposits URANIUM 11 # # # 6 Eldorado Eagle mine (closed) and ABC deposit CITY 13 #19# 8. National Explorations and Eldorado Dubyna mines 7. Golden Heart deposit # 15# 12 ### # 5 22 18 16 # TANTATO # (closed) and Strike deposit 8. EP and Komis mines (closed) 14 1 20 #23 # 10 1 4# 24 # 9. Eldorado Verna, Ace-Fay, Nesbitt Labine (Eagle-Ace) 9. Corner Lake deposit 2 # 5 26 # 10. Tower East and Memorial deposits 17 # ###3 # 25 and Beaverlodge mines and Bolger open pit (closed) Lake Athabasca 21 3 2 10. Martin Lake mine (closed) 11. Birch Crossing deposits Fond du Lac # Black STONY Lake 11. Rix-Athabasca, Smitty, Leonard, Cinch and Cayzor 12. Jojay deposit RAPIDS MUDJATIK Athabasca mines (closed); St. Michael prospect 13. Star Lake mine (closed) # 27 53 12. Lorado mine (closed) 14. Jolu and Decade mines (closed) 13. Black Bay/Murmac Bay mine (closed) 15. Jasper mine (closed) Fond du Lac River 14. -

PROOF June11 2013.Pdf

Contents 2 Letter of Transmittal 3 Message from the Chair and Executive Director 4 Our Board 5 Our Programs 6 2012-13 Community Initiatives Fund Grant Recipients 6 Community Grant Program 29 Community Vitality Program 40 Physical Activity Grant Program 40 Problem Gambling Prevention Program 41 Urban Aboriginal Grant Program 41 Exhibition Associations 41 Youth Engagement 42 Financial Statements of Community Initiatives Fund COMMUNITY INITIATIVES FUND t ANNUAL REPORT 2012-13 1 Message from the Letter of Transmittal Chair and Executive Director The Honourable Kevin Doherty Dear Partners and Community Leaders, Minister of Parks, Culture and Sport, and With considerable pride, we report once again that the Community Initiatives Fund (CIF) has continued to successfully invest in Saskatchewan communities, with 932 grants approved Minister Responsible for the Community Initiatives Fund resulting in a total investment of $10,611,646 for the 2012-13 year. This year also marks a significant milestone for CIF, as we have now invested a cumulative total of over $100 Million in Saskatchewan’s communities since our first year of granting in 1996-97. Our ability to provide grants for the benefit of Saskatchewan residents is reliant upon the annual net revenues generated Dear Hon. Doherty: by the Regina and Moose Jaw casinos, with CIF’s portion in 2012-13 equaling $9,751,000. In accordance with The Tabling of Documents Act, and on behalf of the Board of Trustees of To better support Saskatchewan communities, CIF completed the second phase of its program the Community Initiatives Fund, it is my pleasure to present to you the Annual Report of the Darlene Bessey review this year. -

Saskatchewan Travel Guide

2020 SASKATCHEWAN TRAVEL GUIDE tourismsaskatchewan.com Welcome to Saskat Where time Wakaw Provincial Park chewan and space come together. tourismsaskatchewan.com 2 CONTENTS Need More Information?........................2 Saskatchewan Tourism Areas ................3 Saskatchewan at a Glance......................4 Southern Saskatchewan.........................5 Central Saskatchewan ..........................13 Northern Saskatchewan.......................19 Regina......................................................27 Saskatoon ...............................................31 Traveller Index........................................35 Waskesiu NEED MORE INFORMATION? Let our friendly Travel Counsellors help you plan your Saskatchewan FREE 2020 SASKATCHEWAN vacation. With one toll-free call or click of the mouse, you can receive TRAVEL RESOURCES travel information and trip planning assistance. Saskatchewan Fishing & Hunting Map Service is offered in Canada’s two official languages This colourful map offers – English and French. information about Saskatchewan’s great Le service est disponible dans les deux langues officielles du Canada – fishing and hunting opportunities. l'anglais et le français. CALL TOLL-FREE: 1-877-237-2273 Saskatchewan Official Road Map This fully detailed navigator is a handy tool for touring the province. IMPORTANT NUMBERS CALL 911 in an emergency Travellers experiencing a serious health-related situation, illness or injury should call 911 immediately. Available provincewide, 911 will assist with identifying and dispatching appropriate WEBSITE emergency services. TourismSaskatchewan.com is where you will find a wealth CALL 811 for HealthLine inquiries of great travel planning information, ideas for vacations, road trips, activities and more. You can chat live with a Travel Travellers who may be experiencing a health-related situation, Counsellor. unexpected illness, chronic illness or injury can access professional health advice by dialing 811, the number for Email us at [email protected]. -

Csla Congress 2013 Winds of Change

CSLA CONGRESS 2013 WINDS OF CHANGE Plus! Pre-Conference Workshop Thursday, July 11 Pulling Back the Curtain: Making Sense out of Heritage Landscape Conservation July 10 - 14 Hotel Saskatchewan Regina, SK To be the voice of Dear Colleagues, landscape architects in Please join us in Regina from July 11th-14th for Congress 2013, Canada’s premier Canada and abroad. networking and educational event for the growing landscape architecture profession. The Congress will be an occasion for you, as a member of the landscape architecture community, to network, share in the celebration of the profession’s achievements, and learn from the numerous educational sessions CSLA Congress is the premier and tours. place for Canadian landscape architects to connect, engage, and share. We are pleased to offer a blend of traditional Congress activities, as well as three exciting new events – the CSLA’s first pre-conference workshop, an informal evening session and social following the Welcome Reception, and a Find out what other industry full-day tour of a national historic site. professionals are saying involving: • stormwater management The Congress Planning Committee has developed this expanded Congress to • community engagement showcase ideas, experiences, knowledge, influences and solutions with Prairie • healing gardens flair under the theme of “Winds of Change”. The program and activities reflect • soil innovations the exciting change occurring in the landscape of Saskatchewan, its people, and • transportation design our profession. • and much more! We -

Saskatchewan Arts Board Annual Report 2006-07

Artists. Partnerships. Access. AR 2006-2007 Darren McKenzie Darren McKenzie, a Cree Métis from Saskatchewan, has studied art at Medicine Hat College, the Ontario College of Art and the University of Regina. He also studied intensively for four years with master wood carver Ken Mowatt at the Kitanmaax School of Northwest Coast Indian Art in Hazelton, B.C. The imagery found in Darren’s work is reminiscent of the pre-history of the Northwest Coast peoples, often including the mythology of signifi cant creatures and symbols such as the bear, raven, and sun, as well as the human form. In 2005, Darren realized a dream when he participated in the Changing Hands 2 exhibit, a celebration of North American Indigenous art that opened in New York’s Museum of Art and Design. In May 2009, Darren will have a solo exhibit at the Art Gallery of Regina, where he intends to bring to life through painting, drawing and sculpting, a vision depicting the culmination of his diverse learnings. “There is a power which lives in all of us and we simply have to reach out with our spirits to feel it; all things are bound by it, even stone, water and trees, living, growing, feeling. And when we do, the Creator is pleased, for we are one with Him and shall always be.” – Darren McKenzie Previous page: Darren McKenzie Righteous Apparition, 2005 (#2 from Urban Sentinel series) Cedarwood, hair Photo credit: Don Hall The Honourable Dr. Gordon L. Barnhart Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan Your Honour: The Saskatchewan Arts Board is pleased to submit its annual report for the fi scal year April 1, 2006 to March 31, 2007. -

Preserved AB-SK-MB.Pdf

2014 ALBERTA 3-33 ALBERTA NO. BUILDER SERIAL DATE TYPE NOTES ACADIA VALLEY (32 km SE of Oyen) - Prairie Elevator Museum, Railway Avenue 79827 CN-PSC 1976 CABOOSE ex-CN 79827, c1999; nee CN 472000-series Box Car, (1976) AIRDRIE (30 km north of Calgary) - Nose Creek Valley Museum, Main Street 437030 CP 1942 CABOOSE (wood) nee CP 437030, (1992) ALBERTA BEACH (50 km NW of Edmonton) - private owner NO# CP-Angus 1948 CABOOSE ex-Caboose Lounge/Motel, Onoway, Alberta; (79105) exx-CN 79105:2; nee NAR 13022, (1984) ANDREW (100 km NE of Edmonton) - Ukrainian Village 437378 CP 1949 CABOOSE ex-CP 437378, 1992; exx-CP 439529, 8/1977; nee CP 437378, (5/1967) ARDROSSAN (20 km SE of Edmonton) - Part of a restaurant named “Katie’s Crossing” 600 CC&F 1923 FLAT CAR ex-Private Owner (Tofield, AB) 600, 2001; exx-Alberta Railway Museum 500599, 1998; exxx-Alberta Railway Museum 600; exxxx-CN Box Car 500599 5064 Pullman 8/1914 COACH ex-Private Owner 5064, 2001; exx-Alberta Railway Museum 5064, 1993; exxx-Colonist Car Society 64034; exxxx-CN Work Car 64034; exxxxx-CN Coach 4953:1, 10/1961; exxxxxx-CN Parlor 546 - Joseph, 12/1942; nee GT Parlor 2560, (3/1924) (Under the paint is evidence of the name Colonsay) 18103 Pullman 1917 WORK CAR ex-On-Track Railway Service 18103, 2001; exx-Alberta Railway Museum 18103, 1998; exxx-NAR Shower-Recreation 18103, 1981; exxxx-NAR Sleeper Fairview, 11/1962; nee Pullman ‘12-1' Sleeper Steubenville, (3/1942) 78199 CN-PSC r11/1975 CABOOSE ex-BCOL 78199, 8/1999; exx-CN 78199:2, 1983; exxx-CN 79805, 1983; nee CN 472000-series Box Car, -

President's Message B Oard & Staff Q Uarterly R Eport

VOLUME 6, ISSUE 1 President’s Message SUMMER 2015 is hard to believe a whole year has passed It since my first quarterly report as President last year and how things can change in a year. It was just a year ago where everyone was talking about how much rain we were getting and this year it has been the exact opposite. Life in Saskatchewan is never dull to say the least. As the summer busy season sadly begins to wind down it is time for all of us to look back at all the events and activities that took place in our community and to begin to start looking ahead to Culture Days in late September and onto next year as well. If you have been too busy with all of your activities and you haven’t heard yet the Canada 150 Fund was announced a while back by the Federal Government as a way to celebrate Canada’s 150 birthday, make sure to check out their website for grant opportunities. Celebrations like these only happen once in a lifetime so this is a great opportunity to be part of this historic event. Make sure you let the MAS office know about any of your future events that you plan we can promote your events on our website and in E-Phemera. Also, if you would like a board member to attend any of your upcoming community events, once again just let the office know and we will try our best to accommodate your request. This is another way that we are trying to find different ways to better support our members. -

National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada in Saskatchewan

NationalNational Historic Parks Sites and of Canada in Saskatchewan PLAN A VISIT Prairies, boreal forest, mounted police and early agriculture ... nature and history ... yours to explore! 1 Proudly Bringing You Canada at its Best Land and culture are woven into the tapestry of Canada’s history and the Canadian spirit. The richness of our great country is celebrated in a network of protected places that allow us to understand the land, people and events that shaped Canada. Some things just can’t be replaced and, therefore, your support is vital in protecting the ecological and commemorative integrity of these natural areas and symbols of our past, so they will persist, intact and vibrant, into the future. Discover for yourself the many wonders, adventures and learning experiences that await you in Canada’s national parks, national historic sites, historic canals and national marine conservation areas. Help us keep them healthy and whole — for their sake, for our sake. Iceland Greenland U.S.A. Yukon Northwest Nunavut Territories British Newfoundland Columbia CCaannaaddaa and Labrador Alberta Manitoba Seattle Ontario Saskatchewan Quebec P.E.I. U.S.A. Nova Scotia New Brunswick Chicago New York Our Mission Parks Canada’s mission is to ensure that Canada’s national parks, national historic sites and related heritage areas are protected and presented for this and future generations. These nationally significant examples of Canada’s natural and cultural heritage reflect Canadian values, identity, and pride. 2 CONTENTS Welcome . .4 Batoche National Historic Site . .8 Fort Walsh National Historic Site . .10 Fort Battleford National Historic Site . .12 Motherwell Homestead National Historic Site . -

JUNE Welcome to the June Edition of the E-Voice! Check out All the Events Happening Around the Province This Month

Upcoming Events Greetings from the SAS JUNE Welcome to the June edition of the E-Voice! Check out all the events happening around the province this month. Office Closed Archaeology Centre 3 (1‐1730 Quebec Avenue) JUNE SAS Archaeological Bus Tour 7-9 Stanley Mission and La Ronge JUNE Office Closed Archaeology Centre June is National Indigenous History Month. Celebrate and honour the heritage, contributions and cultures of Indigenous 10-14 (1‐1730 Quebec Avenue) peoples! JUNE Traditional Plant Walk Workshop 16 Saskatoon or Regina area JUNE National Indigenous Peoples Day 21 Everywhere! JUNE Flintknapping Workshop 21 12:00 ‐ 4:00 pm Doc't Town Heritage Photo credit: (https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1466616436543/1534874922512) Village, Kinetic Exhibition Park, Swift Current Stay tuned to our website and social media pages for information on archaeological happenings in the province and JUNE Office Closed across the world. Each week we feature a Saskatchewan archaeological site on our #TBT "Throwback Thursdays" and Archaeology Centre archaeology and food posts on our #FoodieFridays! See our "TrappersandTradersTuesdays" to learn more about the fur 24 (1‐1730 Quebec Avenue) trade card game! JULY Canada Day ‐ Office Closed Just a note that our Drop-In Tuesdays will be taking a break over the Spring and Summer months due to increased out- 1 Archaeology Centre of-office programs and events. Want to stop by to chat and check out what's new? Drop-In Tuesdays will resume on (1‐1730 Quebec Avenue) September 24th! About the SAS **We are always willing to serve you during our regular office hours but as activities increase, please call ahead The Saskatchewan Archaeological if you would like to stop by so we can make sure we are in the office!** Society (SAS) is an independent, charitable, non-profit organization that was founded in 1963.