The Need for a Northern Alberta Development Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quaternary Geology of Northern Alberta: Implications for Kimberlite Exploration

QUATERNARY GEOLOGY OF NORTHERN ALBERTA: IMPLICATIONS FOR KIMBERLITE EXPLORATION M.M. Fenton, J.G. Pawlowicz, R.C. Paulen, G.J. Prior and R.A. Olson Alberta Geological Survey, Alberta Energy and Utilities Board, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada INTRODUCTION the physiography, rarely crops out. Most of the surficial deposits that occur were deposited during the During the last decade, a considerable amount of Pleistocene glaciations. For the most part, the surficial research has taken place in northern Alberta. Particular materials and present-day landforms are a result of the attention has been paid to the unique geological setting last glacial event during the Late Wisconsin (25-12 ka of northern Alberta’s Quaternary history and the BP). challenges of drift prospecting for diamonds here, relative to known methodologies that are well The physiography of northern Alberta (Figure 1) established within the Canadian Shield. Currently, 47 consists of a number of highlands: the Swan Hills, ultramafic diatremes have been discovered in three Pelican Mountains, Saddle Hills, Clear Hills, Naylor separate areas within the Western Canada Sedimentary Hills, Milligan Hills, Buffalo Head Hills, Birch Basin of northern Alberta: 2 non-kimberlitic pipes at Mountains, Caribou Mountains, Cameron Hills, Bootis Mountain Lake, 37 kimberlite pipes in the Buffalo Hills and Elsa Hills. Separating these highlands are Head Hills area and 8 kimberlite pipes in the Birch major drainage ways such as the Peace, Wabasca and Mountains area. The kimberlite fields of northern Athabasca rivers (Pettapiece, 1986). Alberta differ from other Canadian kimberlite fields (e.g. Lac de Gras) in various ways from the perspective BEDROCK GEOLOGY of drift prospecting in glaciated terrain. -

Northern Alberta Mayors' & Reeves' Caucus Denham Inn – Leduc, Alberta Friday, October 16, 2015 10 A.M. – 4:00 P.M

Northern Alberta Mayors’ & Reeves’ Caucus – October 16, 2015 Northern Alberta Mayors’ & Reeves’ Caucus Denham Inn – Leduc, Alberta Friday, October 16, 2015 10 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Present: Deputy Mayor Louise Bauder Town of Gibbons Mayor Melissa Blake Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo Reeve Ron Bobocel Smoky Lake County Councillor Brenda Burridge Town of Fox Creek Mayor Roxanne Carr Strathcona County Mayor Maryann Chichak Town of Whitecourt Mayor William Choy Town of Stony Plain Mayor Craig Copeland City of Cold Lake Mayor Linda Cox Town of High Prairie Mayor Nolan Crouse City of St. Albert Mayor Bill Elliott City of Wetaskiwin Mayor Tom Flynn Sturgeon County Councillor Frank Garritsen City of Fort Saskatchewan Reeve Bart Guyon Brazeau County Mayor Myron Hayduk Town of Vegreville Deputy Mayor Perry Hendriks Town of Beaumont Mayor Lisa Holmes Town of Morinville Mayor Don Iveson City of Edmonton Councillor Jerry Kaup Sturgeon County Mayor Greg Krischke City of Leduc Reeve Bill Lee County of Barrhead Mayor Ralph Leriger Town of Westlock Mayor Stephen Lindop Town of Devon Mayor Vern Lymburner Town of Valleyview Mayor Bruce MacDuff Town of Vermilion Deputy Mayor Elaine Manzer Town of Peace River Reeve Bud Massey Westlock County Mayor Norman Mayer City of Camrose Deputy Mayor Ed McLean City of Spruce Grove Mayor Omer Moghrabi Lac La Biche County Deputy Reeve Ed Parke County of Vermilion River Mayor Greg Pasychny Town of Edson Mayor Kate Patrick Town of Mayerthorpe Page 1 of 15 Northern Alberta Mayors’ & Reeves’ Caucus – October 16, 2015 Mayor -

Northern Alberta Institute of Technology

Northern Alberta Institute of Technology Alternative Energy Program Solar Photovoltaic Reference Array Report – March 31, 2016 Goals Provide solar energy system educators, installers and adopters with real world regional performance data. Improve system design and economic modeling accuracy. Methodology Track individual module performance on as many of the most common installation angles as is possible. Roof pitches of 3/12, 4/12, 6/12 and 12/12 as well as ground installations based on site latitude and wall mounting at 90O were chosen. Study the impact of snow on overall performance for a term of, not less than, five years. Make findings available to any and all interested parties. Design Pairs of Conergy P-230PA solar modules with Enphase M215 microinverters are mounted at 14O, 18O, 27O, 45O, 53O (Edmonton) 55O (Grande Prairie) and 90O. One side or column acts as an unmaintained control while the other column has the snow removed for comparison. Aside from cloud cover the solar array is continuously shade free. Azimuth or facing direction is optimized for Canada, due south. Energy generated is delivered directly to the electrical grid. Project Contacts Dr. Jim Sandercock – NAIT Alternative Energy Program – [email protected] Tim Matthews – NAIT Alternative Energy Program – [email protected] 2 | P a g e Installation One The first site selected was atop NAIT’s South Learning Centre located at 11762 – 106 Street, Edmonton, Alberta. Site latitude, 53O. Ballast mounted. Commissioned April 1, 2012. Edmonton Project Participants Concept – Solar Energy Society of Alberta, Howell Mayhew Engineering. Sponsors – City of Edmonton, NAIT, Alberta Innovates Tech Futures, Howell Mayhew Engineering, Great Canadian Solar. -

Economic Development Strategic Plan

Town of Mayerthorpe Economic Development Strategic Plan March 7, 2017 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................ II 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 PROJECT PROCESS AND REPORT STRUCTURE 1 1.2 FINANCIAL AND BUDGET IMPLICATIONS 2 2 COMPETITIVE POSITION .................................................................................................................................. 3 2.1 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT REVIEW 3 2.2 KEY ECONOMIC INDICATORS 4 2.3 BENCHMARKING TO SIMILAR COMMUNITIES 8 2.4 COMMUNITY SURVEY AND INTERVIEWS 10 2.5 SOAR ASSESSMENT 13 2.6 COMPETITIVE UNIQUENESS 16 3 MOVING FORWARD ......................................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 BUILDING ADMINISTRATIVE AND REGIONAL CAPACITY 17 3.2 ATTRACTING AND SUSTAINING SMALL BUSINESS 18 3.3 RAISING THE COMMUNITY’S PROFILE 19 3.4 GROWING THE NON-RESIDENTIAL ASSESSMENT BASE 20 4 ACTION PLAN ................................................................................................................................................... 21 4.1 VISION STATEMENT 21 4.2 GOALS, OBJECTIVES, ACTIONS DEFINED 21 APPENDIX A: ECONOMIC BASE ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................ -

Chanhee Kwon Dip

Chanhee Kwon Dip. Arch. | Technologist Education Architectural Technology Diploma, Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT), 2011 ROLE Chan provides contract documentation support BIO Already a year out of school, Chan has become an integral part of the ACI team. Chan’s abilities are on par with where his knowledge and comprehension of the industry should be, and they are increasing exponentially as time goes on. Chan provides multicultural insight into his experiences with ACI, that prove invaluable in his dedication and enthusiasm towards any given task or project . His ability to cross reference from/to other languages and views is great value to this team. Chan has already been exposed to a variety of project types, the most recurring of those being in the healthcare sector. Chan will grow and learn with ACI as he becomes more familiar with project tasks and gains confidence in his skills. EXPERIENCE Health and Wellness Alberta Health Services Northeast Community Health centre Ambulance bay addition Edmonton, AB Alberta Health Services Mayerthorpe Healthcare Centre Landscape & Sidewalk Mayerthorpe, AB Alberta Health Services Wabasca housing Re-cladding Wabasca, AB Alberta Health Services Athabasca Trauma Room Athabasca, AB Alberta Health Services Cross Cancer Institute Roof Replacement Edmonton, AB Additional Projects International Union of Operating Engineers Operating Engineers Building Fort McMurray, AB “Change is inevitable, and the speed of change dramatically increases as the time goes by. Therefore we accept and adopt. We are in constant evolution where we have to learn and adopt new technologies, new products, new designs, different cultures, and environment. We study, adopt, and analyze these complex problems to propose one final design that suits the need of people and is a delight to look at. -

(WNC) Thursday, May 11, 2017 Cold Lake, AB

Draft Minutes for Approval at September 14, 2017 Meeting MINUTES Water North Coalition (WNC) Thursday, May 11, 2017 Cold Lake, AB Attendees Jennifer Besinger, County of Grande Prairie Bob Buckle, City of Cold Lake Tom Burton, AAMDC Simon Cardinal, MD of Opportunity Kevin Dube, Big Lakes County Marie Dyck, Northern Sunrise County Sandra Eastman, M.D. of Peace Jennifer Espanol, Alberta Municipal Services Corporation Michelle Gairdner, City of Grande Prairie Earl Gullion, MD of Opportunity Colin Hanusz, Beaver River Watershed Alliance Marsha Hayward, Beaver River Watershed Alliance Lindsay Johnson, Advanced Technology Applications Josh Knelsen, Mackenzie County Dana Langer, Town of Peace River Duane Lay, City of Cold Lake Roger Loberg, Town of Beaverlodge Vern Lymburner, Town of Valleyview Sean McCallum, town of Wembley Devin Meneen, TSGA Bob Marshall, County of Grande Prairie Mary Nelson, Town of Grande Cache Dan Rites, Alberta Water & Wastewater Operators Ken Shaw, Gift Lake Metis Settlement MJ Siebold, Lac La Biche County Ray Skrepnek, M.D. of Fairview Keith Straub, Town of High Level Chris Thiessen, City of Grande Prairie Reuel Thomas, Portage College Ken Titford, Saddle Hills County Brad Trimble, Town of Bonnyville Andre Trudeau, M.D. of Smoky River No. 130 Fred Wiebe, Mackenzie County Ian Willier, Big Lakes County Administration Brittany Bingham, Northern Alberta Development Council Anne Okaley, Northern Alberta Development Council Kim Pinnock, Northern Alberta Development Council Nicole Renaud, Northern Alberta Development Council Susan Shave, Northern Alberta Development Council 1 Draft Minutes for Approval at September 14, 2017 Meeting Speakers Joey Hurley, Alberta Environment and Parks Sidney Manning, Alberta Municipal Affairs Jessica Popadynetz, Alberta Health Services Rosey Radmanovich, Technical Services Advisory Group Welcome and Introductions Bob Marshall, Chair, introduced Kevin Nagoya, Chief Administrative Officer, City of Cold Lake. -

Grande Prairie/Peace River Region)

JOB POSTING Small Business Strategist – Northern Alberta (Grande Prairie/Peace River Region) Business Link is Alberta’s small business hub. We direct and connect Alberta’s small businesses to relevant support, ensuring they have information needed to start, grow and be successful. Our team members are passionate about Alberta small business and exemplify entrepreneurial spirit and capabilities. We are guided by our values of respect, integrity, collaboration, and innovation. Do you have a side hustle, are you an entrepreneur? Have you worked with entrepreneurs and small businesses in the past? Then we want you. Business Link is looking to fill the position of Small Business Strategist – Grande Prairie/Peace River Region reporting to the Team Lead, Small Business Strategists. The ideal candidate will play an essential role in small business success. We seek a trusted advisor, who can provide meaningful and value-based service offerings to our clients with an open and receptive approach. The ideal candidate thrives on building deeper relationships with clients, ecosystem partners and industry stakeholders and takes pride in contributing to entrepreneurial success. This role will be based in the Grande Prairie/Peace River Region of Northern Alberta and will support small businesses in the region, delivering business education and providing one on one business advisory to small businesses. Qualifications • Degree in Business or a related field, or diploma in Business with 2 years of professional experience. • Previous entrepreneurial, business incubator and/or accelerator experience. • Strong business acumen and an understanding of small business and entrepreneurship. • Valid Alberta driver’s license. • Candidate must reside in the Grande Prairie/Peace River Regions of Northern Alberta. -

ALASKA and NORTHWESTERN CANADA Weather and Climate Highlights and Impacts, Dec 2020 - Feb 2021; Climate Outlook April - June 2021

ALASKA and NORTHWESTERN CANADA Weather and Climate Highlights and Impacts, Dec 2020 - Feb 2021; Climate Outlook April - June 2021 1 Dec 2020-Feb 2021 Temperature Averages (°F/°C) & Anomalies- Below. / .Above / Normal. Thick Fog and Issues with COVID Vaccine Rollout In Yukon, the COVID-19 vaccine rollout is well underway. The first doses were administered on January 4 to residents and employees of long-term care homes. Two mobile vaccination clinical teams – Team Balto and Team Togo – began vaccinating Yukoners in rural communities on January 18. Now on their second round of community visits, both teams have shown dedication and have adapted to changing weather conditions along the way. Thick fog caused a significant flight delay for Team Balto’s trip to Old Crow in January. The team arrived six hours later than expected, but they were able to set up the clinic in record time and run a successful clinic with just a three-hour delay. In Dawson City, Team Togo faced the unique challenge of managing heavy traffic and potentially long wait times in -36 degree weather with ease, and received positive feedback from the community. The mobile clinics have been met with enthusiasm in every Yukon community. Special mention goes to the community of Haines Junction, who lined the highway with hundreds of ice candles to celebrate Team Togo’s arrival. As of March 3, 2021, a total of 19,437 doses have been administered in the territory, including 12,344 first doses and 7,093 second doses. Vaccines are now available to the general public in Whitehorse. -

New Developments in Emergency Preparedness in Alberta

New Developments in Emergency Preparedness in Alberta Following the 2011 Slave Lake wildfires, the Alberta government introduced several changes to Alberta’s emergency preparedness system in Alberta under government’s plan to improve Public Safety Governance. Many were already in development or being planned. The recommendations in the KPMG report Lesser Slave Lake Regional Urban Interface Wildfire Lessons Learned Report align with these initiatives, some of which include: The steps taken during the response to the Slave Lake wildfires were thoroughly assessed and reviewed (including the evacuation, reception centre coordination, and re-entry). The best practices have been utilized during more recent emergency events in the province, such as the Mackenzie County wildfires in northern Alberta in 2012. The Emergency Management Act was amended in 2011 to support local authorities establishing regional approaches to emergency management. With this amendment there are now four approaches for communities to take with regionalizing: o mutual aid agreements reinforced by regional Emergency Operations Centers, plans and exercises; o creating a Regional Services Commission through legislation; o creating a Regional Emergency Management committee through a ministerial order; or o a summer village may delegate its powers to another local authority that agrees to accept the responsibility. Alberta's Emergency Alert system was upgraded in 2011 to make use of the latest technology to send out critical, life-saving information to Albertans over the internet, radio, television, and social media. The new system is unique in North America. It empowers local communities to issue alerts and quickly get emergency information directly to the public. Roles and responsibilities have been clarified among local and provincial public safety partners. -

Alberta's Caribou

Alberta’s Caribou: A Guide to Range Planning Vol. 1: Northeast Alberta Alberta’s Caribou: A Guide to Range Planning Vol. 1: Northeast Alberta Authored by: Tara Russell Danielle Pendlebury Alison Ronson With thanks to Jaymie Campbell, Dr. Dave Hervieux, Dr. Elston Dzus and Dr. Liv Vors. Copyright 2016: Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, Northern Alberta CPAWS Northern Alberta PO Box 52031 Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2T5 Generously Funded By: www.cpawsnab.org cpaws.northernalberta @CPAWSNAB cpaws_nab The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now. – Chinese Proverb Caribou - P Mather Table of Contents Introduction 1 Boreal Woodland Caribou in Alberta 1 Life history and Habitat Requirements 1 Issues and threats 2 Current Legal Status 2 The Federal Recovery Strategy and Range Planning 2 Boreal Woodland Caribou Management 4 History of Management Planning 4 Decline in Boreal Woodland Caribou in Alberta 6 Industrial Activity in Caribou Ranges in Alberta 10 Undisturbed Critical Habitat in Boreal Woodland Caribou Ranges in Alberta 18 Conservation Value of Boreal Woodland Caribou Ranges in Alberta 22 Home Range for Boreal Woodland Caribou Herds in Alberta 26 Restoration Priority Areas for Boreal Woodland Caribou Ranges in Alberta 26 Summary: Recommendations Based on Range Modeling 35 Protected Areas in Alberta 35 Restoration 36 Best Management Practices 37 Involvement in Range Planning 38 Aboriginal Communities 38 Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations 39 Industry Initiatives 39 Forestry 39 Oil and Gas 40 Government Commitments 41 Conclusion 41 Glossary of Terms 42 References 43 Appendix 1: Industry Present in Northeast Caribou Ranges 46 Mossy Boreal - M Berkman Introduction Boreal woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) are an iconic Canadian species: they have provided sustenance to Aboriginal communities for thousands of years, their silhouette graces our 25 cent coin, and they are a symbol of a healthy forest. -

Overview of a Project Aiming to Assess Environmental Impacts of Oil and Gas Activities in the Fox Creek Area (AB)

Overview of a project aiming to assess environmental impacts of oil and gas activities in the Fox Creek area (AB) C. Rivard1, D. Lavoie1, E. Konstantinovskaya2, B. Smerdon3, O. Haeri Ardakani1, C. Paniconi 4, J. Lovitt5, G. Bordeleau 4, A. Bahramiyarahmadi 2, L.I. Guarin-Martinez 1,4, R. Chalaturnyk6, D. Alessi2, S. Safari2, K. von Gunten2, B. Xu.7, A. Mort1, H. Kao1, R. Lavoie 8, P. Leblanc-Rochette 1,8, S. Heckbert3, D. Jiang1, B. Giroux 4, A.C. Dip 4, I. Aubin9, D. Degenhardt9, J. Harvey 9, S. Leblanc5, H.P. White5, S. Grasby 1 1 Geological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada (NRCan); 2 University of Alberta, Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences 3 Alberta Energy Regulator 4 Institut national de la recherche scientifique – Eau Terre Environnement (INRS-ETE) 5 CCMEO, Natural Resources Canada 6 University of Alberta, Faculty of Engineering 7 Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) 8 Université Laval, École supérieure d'aménagement du territoire et de développement régional 9 Canadian Forest Service, Natural Resources Canada Summary A multidisciplinary and multi-institutional project was initiated in the Fox Creek area, in west- central Alberta, in 2019 to study environmental impacts of hydrocarbon exploration and production activities. The initial objective was to specifically study potential impacts on shallow groundwater. However, different Sectors within NRCan later identified the Fox Creek area as a region of interest for developing regional cumulative effects evaluation methods in support of new impact assessment legislation. Therefore, the project scope is now much larger and includes studies on vegetation, forest, woodland caribous, wetlands, landscape and atmospheric emissions, and involves many collaborators from the federal and provincial governments, and academia. -

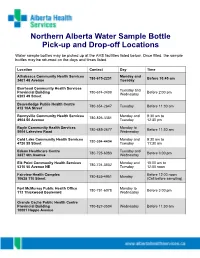

Northern Alberta Water Sample Bottle Pick-Up and Drop-Off Locations.Pub

Northern Alberta Water Sample Bottle Pick-up and Drop-off Locations Water sample bottles may be picked up at the AHS facilities listed below. Once filled, the sample bottles may be returned on the days and times listed. Location Contact Day Time Athabasca Community Health Services Monday and 780-675-2231 Before 10:45 am 3401 48 Avenue Tuesday Barrhead Community Health Services Tuesday and Provincial Building 780-674-3408 Before 2:00 pm Wednesday 6203 49 Street Beaverlodge Public Health Centre 780-354-2647 Tuesday Before 11:30 am 412 10A Street Bonnyville Community Health Services Monday and 9:30 am to 780-826-3381 4904 50 Avenue Tuesday 12:30 pm Boyle Community Health Services Monday to 780-689-2677 Before 11:30 am 5004 Lakeview Road Wednesday Cold Lake Community Health Services Monday and 9:30 am to 780-594-4404 4720 55 Street Tuesday 11:30 am Edson Healthcare Centre Tuesday and 780-725-6083 Before 3:00 pm 3837 6th Avenue Wednesday Elk Point Community Health Services Monday and 10:00 am to 780-724-3532 5310 50 Avenue NE Tuesday 12:00 noon Fairview Health Complex Before 12:00 noon 780-835-4951 Monday 10628 110 Street (Call before sampling) Fort McMurray Public Health Office Monday to 780-791-6078 Before 3:00 pm 113 Thickwood Boulevard Wednesday Grande Cache Public Health Centre Provincial Building 780-827-3504 Wednesday Before 11:30 am 10001 Hoppe Avenue Location Contact Day Time Grande Prairie Environmental Public Monday to Health, Provincial Building 780-513-7517 Before 1:30 pm Wednesday 10320 99 Street High Level Monday to 10:00 am to Northwest Health Centre 780-841-3252 Wednesday 4:00 pm 11202 100 Avenue High Prairie Health Complex Monday to 9:00 a.m.