Medically Valid Religious Beliefs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Essay: Religion and Politics 2008-2009: Sometimes You Get What You Pray For

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2010 Review Essay: Religion and Politics 2008-2009: Sometimes You Get What You Pray For Leslie C. Griffin University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Law and Politics Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Griffin, Leslie C., "Review Essay: Religion and Politics 2008-2009: Sometimes You Get What You Pray For" (2010). Scholarly Works. 803. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/803 This Article is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW ESSAY RELIGION AND POLITICS 2008-2009 THUMPIN' IT: THE USE AND ABUSE OF THE BIBLE IN TODAY'S PRESIDENTIAL POLITICS. By Jacques Berlinerblau. Westminster John Knox Press 2008. Pp. x + 190. $11.84. ISBN: 0-664-23173-X. THE SECULAR CONSCIENCE: WHY BELIEF BELONGS IN PUBLIC LIFE. By Austin Dacey. Prometheus Book 2008. Pp. 269. $17.80. ISBN: 1-591- 02604-0. SOULED OUT: RECLAIMING FAITH AND POLITICS AFTER THE RELIGIOUS RIGHT. By E.J Dionne, Jr.. Princeton University Press 2008. Pp. 251. $14.95. ISBN: 0-691-13458-8. THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF RELIGIOUS LIBERTY By Anthony Gill. Cambridge University Press 2007. Pp. 263. Paper. $18.81. ISBN: 0-521- 61273-X. BLEACHED FAITH. THE TRAGIC COST WHEN RELIGION IS FORCED INTO THE PUBLIC SQUARE. By Steven Goldberg. -

Hurrah for Freedom of Inquiry

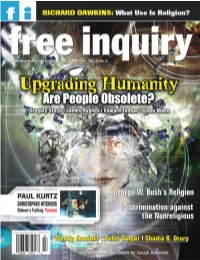

FI Feb-Mar 2006 Pages 1/3/06 11:34 AM Page 4 EDITORIAL FI Editorial Staff PAUL KURTZ Editor in Chief Paul Kurtz Editor Thomas W. Flynn Associate Editors Nathan Bupp, Austin Dacey, David Koepsell Managing Editor Deputy Editor Andrea Szalanski Norm R. Allen Jr. Columnists Vern Bullough, Arthur Caplan, Richard Dawkins, Shadia B. Drury, Sam Harris, Nat Hentoff, Christopher Hitchens, Wendy Kaminer, Tibor R. Machan, Peter Singer Ethics Editor Elliot D. Cohen Literary Editor Jennifer Michael Hecht Senior Editors Vern L. Bullough, Bill Cooke, Hurrah for Richard Dawkins, Martin Gardner, James A. Haught, Jim Herrick, Gerald A. Larue, Taslima Nasrin Freedom of Inquiry: Contributing Editors Jo Ann Boydston, Albert Ellis, Roy P. Fairfield, Charles Faulkner, Antony Flew, Levi Fragell, Adolf Grünbaum, Marvin Kohl, Thelma Lavine, Lee Nisbet, J.J.C. Smart, Vital Issues for Svetozar Stojanovi´c, Thomas Szasz Editorial Associate DJ Grothe Secular Humanists Editorial Assistant David Park Musella Art Director Lisa A. Hutter here is an ongoing debate among secular humanists as to Production what our priorities should be, and in particular, what Christopher Fix, Paul E. Loynes Sr. should be the primary focus of FREE INQUIRY. Two subjects Cartoonist Webmaster Don Addis Kevin Christopher have been among the most hotly debated. First is the burn- Contributing Illustrators T ing desire of many secular humanists that we engage in political Brad Marshall, Todd Julie activism. Many secularists, naturalists, and humanists believe that Cover Illustration Todd Julie the United States faces so many critical problems that we need to focus far more intensely on the political battles of today, especially Council for Secular Humanism the culture wars with the Religious Right. -

Blasphemy As Violence: Trying to Understand the Kind of Injury That Can Be Inflicted by Acts and Artefacts That Are Construed As Blasphemy

Journal of Religion in Europe Journal of Religion in Europe 6 (2013) 35–63 brill.com/jre Blasphemy As Violence: Trying to Understand the Kind of Injury That Can Be Inflicted by Acts and Artefacts That Are Construed As Blasphemy Christoph Baumgartner Faculty of Humanities, Utrecht University [email protected] Abstract This article suggests an understanding of blasphemy as violence that enables us to identify various kinds of injury that can be inflicted by blasphemous acts and artefacts. Understanding blasphemy as violence can take three forms: physical violence, indirect intersubjective violence, and psychological violence. The condi- tions that allow for an understanding of blasphemy as physical violence depend on very specific religious assumptions. This is different in the case of indirect intersubjective violence that can take effect in social circumstances where certain forms of blasphemy reinforce existing negative stereotypes of believers. The analy- sis of blasphemy as psychological violence reveals that interpretations according to which believers who take offense to blasphemy are ‘backward’ and ‘unenlight- ened’ do not suffice to explain the conditions of the insult that is felt by some believers. The article shows that these conditions can be explained by means of Harry Frankfurt’s philosophical theory of caring. Keywords anti-religious racism; blasphemy; caring; offense; violence 1. Introduction In recent years, acts and artefacts that were perceived as blasphemous by numerous believers received much attention in public debate as well as in scholarly literature. This concerns the various aspects and interests which motivated public statements and demonstrations for or against such acts © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2013 DOI 10.1163/18748929-00601007 36 C. -

FI-AS-08.Pdf

COVER CENTERS FOR INQUIRY •• www.centerforinquiry.net/about/centerswww.centerforinquiry.net/about/centers CFI/BUENOS AIRES (ARGENTINA) Ormond Beach, Fla. 32175 DOMESTIC Ex. Dir.: Alejandro Borgo Tel.: (386) 671-1921 Buenos Aires, Argentina email: [email protected] CFI/TRANSNATIONAL Founder and Chair: Paul Kurtz CFI/CAIRO (EGYPT) CFI Community/ Ex. Dir.: Barry Karr Chairs: Prof. Mona Abousenna Fort Lauderdale PO Box 703, Prof. Mourad Wahba President: Jeanette Madea Amherst, N.Y. 14226 44 Gol Gamal St., Agouza, Giza, Egypt Tel.: (954) 345-1181 Tel: (716) 636-4869 CFI/GERMANY (ROSSDORF) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Ex. Dir.: Amardeo Sarma CFI Community/Harlem CFI/AUSTIN Kirchgasse 4, 64380 Rossdorf, Germany President: Sibanye Ex. Dir.: Jenni Acosta Rossdorf, Germany Email: [email protected] PO Box 202164, CFI/INDIA (HYDERABAD) CFI Community/Long Island Austin, Tex. 78720-2164 Ex. Dir.: Prof. Innaiah Narisetti President: Gerry Dantone Tel: (512) 919-4115 Hyderabad, India PO Box 119 Email: [email protected] CFI/ITALY Greenlawn, N.Y. 11740 CFI/CHICAGO Ex. Dir.: Hugo Estrella Tel.: (516) 640-5491 Email: [email protected] Ex. Dir.: Adam Walker CFI/KENYA (NAIROBI) PO Box 7951, Ex. Dir.: George Ongere CFI Community/Miami Chicago, Ill. 60680-7951 President: Argelia Tejada Tel: (312) 226-0420 CFI/LONDON (U.K.) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Ex. Dir.: Suresh Lalvani Conway Hall, 25 Red Lion Square, CFI Community/Naples (Florida) CFI/INDIANA London WC1R 4RL, England Coordinator: Bernie Turner Ex. Dir.: Reba Boyd Wooden 801 Anchor Rode Ave. 350 Canal Walk, Suite A, CFI/LOW COUNTRIES Suite 206 Indianapolis, Ind. -

HIST351-2.3.2-Sharia.Pdf

Sharia 1 Sharia . šarīʿah, IPA: [ʃaˈriːʕa], "way" or "path") is the code of conduct or religious law of Islamﺷﺮﻳﻌﺔ :Sharīʿah (Arabic Most Muslims believe Sharia is derived from two primary sources of Islamic law: the precepts set forth in the Qur'an, and the example set by the Islamic Prophet Muhammad in the Sunnah. Fiqh jurisprudence interprets and extends the application of Sharia to questions not directly addressed in the primary sources by including secondary sources. These secondary sources usually include the consensus of the religious scholars embodied in ijma, and analogy from the Qur'an and Sunnah through qiyas. Shia jurists prefer to apply reasoning ('aql) rather than analogy in order to address difficult questions. Muslims believe Sharia is God's law, but they differ as to what exactly it entails.[1] Modernists, traditionalists and fundamentalists all hold different views of Sharia, as do adherents to different schools of Islamic thought and scholarship. Different countries and cultures have varying interpretations of Sharia as well. Sharia deals with many topics addressed by secular law, including crime, politics and economics, as well as personal matters such as sexuality, hygiene, diet, prayer, and fasting. Where it enjoys official status, Sharia is applied by Islamic judges, or qadis. The imam has varying responsibilities depending on the interpretation of Sharia; while the term is commonly used to refer to the leader of communal prayers, the imam may also be a scholar, religious leader, or political leader. The reintroduction of Sharia is a longstanding goal for Islamist movements in Muslim countries. Some Muslim minorities in Asia (e.g. -

Evangelical Atheists’ Editorial Assistant Julia Lavarnway Art Director Too Outspoken? Lisa A

FI Feb-Mar 07 Pages 12/26/06 12:43 PM Page 4 FI Editorial Staff EDITORIAL Editor in Chief PAUL KURTZ Paul Kurtz Editor Thomas W. Flynn Associate Editors Norm R. Allen Jr., Nathan Bupp, Austin Dacey, D.J. Grothe, R. Joseph Hoffmann, David Koepsell, John R. Shook Managing Editor Andrea Szalanski Columnists Arthur Caplan, Richard Dawkins, Shadia B. Drury, Sam Harris, Nat Hentoff, Christopher Hitchens, Wendy Kaminer, Tibor R. Machan, Peter Singer Senior Editors Bill Cooke, Richard Dawkins, Martin Gardner, James A. Haught, Jim Herrick, Gerald A. Larue, Ronald A. Lindsay, Taslima Nasrin Contributing Editors Jo Ann Boydston, Albert Ellis, Roy P. Fairfield, Charles Faulkner, Antony Flew, Levi Fragell, Adolf Grünbaum, Religion in Conflict Marvin Kohl, Thelma Lavine, Lee Nisbet, J.J.C. Smart, Svetozar Stojanovi´c, Thomas Szasz Ethics Editor Elliot D. Cohen Literary Editor and Assistant Editor David Park Musella Are ‘Evangelical Atheists’ Editorial Assistant Julia Lavarnway Art Director Too Outspoken? Lisa A. Hutter Production Christopher Fix, Paul E. Loynes Sr. he recent publication of four books—The God Delusion, by Cartoonist Webmaster Richard Dawkins; The End of Faith and Letter to a Don Addis Robert Greiner Christian Nation, both by Sam Harris; and Breaking the TSpell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon by Daniel Dennett—has provoked great controversy and consternation.* The Council for Secular Humanism fact that books by Dawkins and Harris have made it to The New Chair Paul Kurtz York Times best-seller list has apparently sent chills down the spines of many commentators; not only conservative religionists but Board of Directors Derek Araujo, Thomas Casten, Kendrick Frazier, also some otherwise liberal secularists are worried about this unex- David Henehan, Lee Nisbet, Jonathan Kurtz, pected development. -

The Vietnam Draft Cases and the Pro-Religion Equality Project

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 43 Article 2 Issue 1 Spring 2014 2014 The ietnV am Draft aC ses and the Pro-Religion Equality Project Bruce Ledewitz Duquesne University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Ledewitz, Bruce (2014) "The ieV tnam Draft asC es and the Pro-Religion Equality Project," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 43: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol43/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VIETNAM DRAFT CASES AND THE PRO-RELIGION EQUALITY PROJECT Bruce Ledewitz* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... ! II. WHY TOLERATE RELIGION? ............................................... 5 III. THE ANTI-RELIGION EQUALITY PROJECT IN CONTEXT ............................................................................... l6 IV. EVALUATING LEITER'S PROJECT ................................... 30 V. THE PRO-RELIGION EQUALITY PROJECT ...................... 38 VI. THE VIETNAM DRAFT CASES .......................................... .47 VII. THE LIMITATIONS OF CONSCIENCE CLAUSES ............ 61 VIII. -

FI-June-July-04.Pdf

THE AFFIRMATIONS OF HUMANISM: A STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES* We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems. We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation. We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life. We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities. We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state. We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual understanding. We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance. We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves. We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual orientation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity. We want to protect and enhance the earth, to preserve it for future generations, and to avoid inflicting needless suffering on other species. We believe in enjoying life here and now and in developing our creative talents to their fullest. We believe in the cultivation of moral excellence. We respect the right to privacy. Mature adults should be allowed to fulfill their aspirations, to express their sexual preferences, to exercise reproductive freedom, to have access to comprehensive and informed health-care, and to die with dignity. -

Religious Skepticism, Atheism, Humanism, Naturalism, Secularism, Rationalism, Irreligion, Agnosticism, and Related Perspectives)

Unbelief (Religious Skepticism, Atheism, Humanism, Naturalism, Secularism, Rationalism, Irreligion, Agnosticism, and Related Perspectives) A Historical Bibliography Compiled by J. Gordon Melton ~ San Diego ~ San Diego State University ~ 2011 This bibliography presents primary and secondary sources in the history of unbelief in Western Europe and the United States, from the Enlightenment to the present. It is a living document which will grow and develop as more sources are located. If you see errors, or notice that important items are missing, please notify the author, Dr. J. Gordon Melton at [email protected]. Please credit San Diego State University, Department of Religious Studies in publications. Copyright San Diego State University. ****************************************************************************** Table of Contents Introduction General Sources European Beginnings A. The Sixteenth-Century Challenges to Trinitarianism a. Michael Servetus b. Socinianism and the Polish Brethren B. The Unitarian Tradition a. Ferenc (Francis) David C. The Enlightenment and Rise of Deism in Modern Europe France A. French Enlightenment a. Pierre Bayle (1647-1706) b. Jean Meslier (1664-1729) c. Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach (1723-1789) d. Voltaire (Francois-Marie d'Arouet) (1694-1778) e. Jacques-André Naigeon (1738-1810) f. Denis Diderot (1713-1784) g. Marquis de Montesquieu (1689-1755) h. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) B. France and Unbelief in the Nineteenth Century a. August Comte (1798-1857) and the Religion of Positivism C. France and Unbelief in the Twentieth Century a. French Existentialism b. Albert Camus (1913 -1960) c. Franz Kafka (1883-1924) United Kingdom A. Deist Beginnings, Flowering, and Beyond a. Edward Herbert, Baron of Cherbury (1583-1648) b. -

September 6, 2015 1 the Organization Holds Conferences and Events

AJBT Volume 16 (36), September 6, 2015 WARRANTED SKEPTICISM? PUTTING THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY’S RATIONALE TO THE TEST Dr. Scott Ventureyra Abstract: The aim of this article is to take the Center for Inquiry’s ((CFI) a highly influential organization in the west), mission statement to task with respect to their critique of supposed extraordinary claims through the application of Carl Sagan’s quote: “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” Specifically those which are defensible through rational argumentation (God’s existence) i.e., in order to question whether or not they are actually promoting rigorous critical thought through the utilization of science and reason. A look will be also taken into whether they are actually fostering freedom of inquiry or if they are becoming masterful at insulating themselves from any criticisms against their own respective position. This will be carried forth through the examination of the following: i) emotions and non-belief, ii) the epistemology of Carl Sagan’s quote, iii) philosophy, science and the question of God, iv) the presumption of atheism and its relation to Sagan’s quote, v) proper basicality and Sagan’s quote and vi) Jesus’ resurrection as a test case. Keywords: atheism; Carl Sagan; Center for Inquiry; existence of God; “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”; God; Jesus’ resurrection; philosophy; presumption of atheism; proper basicality; science; skepticism INTRODUCTION Several years ago, throughout North America and England, the Center for Inquiry (CFI), a secular humanist organization, that has branches throughout the world,1 placed a series of advertisements on public 1 The organization holds conferences and events where many prominent atheist philosophers and scientists such as Stephen Law, Daniel Dennett, Keith Parsons, John Shook, Richard Dawkins and 1 Scott Ventureyra transportation buses. -

The New New Secularism and the End of the Law of Separation of Church and State

Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal Volume 28 Article 1 9-1-2009 The New New Secularism and the End of the Law of Separation of Church and State Bruce Ledewitz Duquesne University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Bruce Ledewitz, The New New Secularism and the End of the Law of Separation of Church and State, 28 Buff. Envtl. L.J. 1 (2009). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj/vol28/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW NEW SECULARISM AND THE END OF THE LAW OF SEPARATION OF CHURCH AND STATE BRUCE LEDEWITZt "There should .. be a service designed for those without a 1 religion." INTRODUCTION There is a general feeling today among American legal thinkers that the constitutional principle of separation of church 2 and state is not enforceable, at least not to the extent it used to be. A five-Justice majority on the United States Supreme Court stands poised to overturn, formally or informally, the vaunted Lemon test and replace it with some sort of permissive formulation that will allow a substantial amount of religious symbolism in the public square, as well as public support for various kinds of religious institutions. -

Islam’S War Against the West

RICHARD DAWKINS spills the Elixir of Holiness Celebratingf Reason and Humanity SPRING 2002 • VOL. 22 No. 2 Pervez HOODBHOY •• IbnWARRAQ •• IbnAL-RAWANDI AntonyFLEW: Islam’s War Against the West PauPaull AnAn AtheistAtheist KURKURTTZZ oonn atat WarWar FairFair Play,Play, ImprisonmenImprisonmentt,, NatNat && IIsraelsrael HENTOFFHENTOFF •• PeterPeter WendWendyy SINGERSINGER KAMINERKAMINER onon •• SSuurveillancerveillance TiborTibor R.R. && LibeLiberrttyy MACHANMACHAN • RoyRoy • ToTomm BROWNBROWN FLYNN:FLYNN: JohnJohn A.A. •• WhatWhat FRANTZFRANTZ Victory in Victory in ChristopherChristopher •• Afghanistan?Afghanistan? HITCHENSHITCHENS JoanJoan KennedyKennedy •• Introductory Price $5.95 U.S. / $6.95 Can. TAYLOR 21> TAYLOR KatherineKatherine •• BOURDONNAYBOURDONNAY 7725274 74957 Published by The Council for Secular Humanism •• THE AFFIRMATIONS OF HUMANISM: A STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems. We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation. We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life. We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities. We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state. We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual understanding. We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance. We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves. We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual orientation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity.