A Synopsis of Feline Infectious Peritonitis Virus Infection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generalized Edema Resulting from Mixed Intestinal Infection by Entamoebia Histolytica and E

Case Report JOJ Case Stud Volume 12 Issue 2 -April 2021 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Ajite Adebukola DOI: 10.19080/JOJCS.2021.12.555833 Generalized Edema Resulting from Mixed Intestinal Infection by Entamoebia Histolytica and E. Coli in a Nigerian Female Adolescent: A Case Report Ajite Adebukola1,2*, Oluwayemi Oludare1,2 and Fatunla Odunayo2 1Department of Paediatrics, Ekiti State University, Nigeria 2Department of Paediatrics, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria Submission: March 15, 2021; Published: April 08, 2021 *Corresponding author: Ajite Adebukola, Consultant Paediatrician, Department of Paediatrics, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria Abstract Amoebiasis, a clinical condition caused by Entamoeba histolytica does not usually present with generalized oedema known as anarsarca. We present a case of an adolescent female Nigerian who was admitted on account of chronic diarrhea and anarsarca in a tertiary hospital, Southwest Nigeria. There was no proteinuria. She however had cyst of E. histolytica and growth of E. coli in her stool; she also had E. coli isolated in her urine. She had hypoproteinaemia (35.2g/L) and hypoalbuminaemia (21.3g/L) as well as hypokalemia (2.97mmol/L). Symptoms resolved Entamoeba histolytica and Escherichia coli bacteria may be responsible for the worse clinical manifestations of Amoebiasis and biochemical parameters normalized following treatment with Nitrofurantoin, Tinidazole and Ciprofloxacin. A mixed infection of Keywords: Amoebiasis; Chronic diarrhea; Hypoproteinaemia; Anasarca Introduction Amoebiasis, caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica of amenorrhoea. is an infection that frequently manifests clinically with symptoms recurrent generalized body swelling, and a seven-month history of abdominal pain, diarrhoea, dysentery and weight loss [1,2]. -

Abyssinian Cat Club Type: Breed

Abyssinian Cat Association Abyssinian Cat Club Asian Cat Association Type: Breed - Abyssinian Type: Breed – Abyssinian Type: Breed – Asian LH, Asian SH www.abycatassociation.co.uk www.abyssiniancatclub.com http://acacats.co.uk/ Asian Group Cat Society Australian Mist Cat Association Australian Mist Cat Society Type: Breed – Asian LH, Type: Breed – Australian Mist Type: Breed – Australian Mist Asian SH www.australianmistcatassociation.co.uk www.australianmistcats.co.uk www.asiangroupcatsociety.co.uk Aztec & Ocicat Society Balinese & Siamese Cat Club Balinese Cat Society Type: Breed – Aztec, Ocicat Type: Breed – Balinese, Siamese Type: Breed – Balinese www.ocicat-classics.club www.balinesecatsociety.co.uk Bedford & District Cat Club Bengal Cat Association Bengal Cat Club Type: Area Type: PROVISIONAL Breed – Type: Breed – Bengal Bengal www.thebengalcatclub.com www.bedfordanddistrictcatclub.com www.bengalcatassociation.co.uk Birman Cat Club Black & White Cat Club Blue Persian Cat Society Type: Breed – Birman Type: Breed – British SH, Manx, Persian Type: Breed – Persian www.birmancatclub.co.uk www.theblackandwhitecatclub.org www.bluepersiancatsociety.co.uk Blue Pointed Siamese Cat Club Bombay & Asian Cats Breed Club Bristol & District Cat Club Type: Breed – Siamese Type: Breed – Asian LH, Type: Area www.bpscc.org.uk Asian SH www.bristol-catclub.co.uk www.bombayandasiancatsbreedclub.org British Shorthair Cat Club Bucks, Oxon & Berks Cat Burmese Cat Association Type: Breed – British SH, Society Type: Breed – Burmese Manx Type: Area www.burmesecatassociation.org -

Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD)

Polycystic Kidney Disease About the disease Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (AD-PKD) is a problem in Persian cats and related breeds, especially Chinchillas, Exotics and British Shorthairs. The Molecular Diagnostic Unit has been oFFering a genetic test to diagnose autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (AD-PKD) in cats since April 2005 About the test This genetic test is a PCR-based pyrosequencing assay and evaluations oF the test have shown excellent agreement with the results oF ultrasound screening. The test has revolutionised testing For AD-PKD. Until recently specialist ultrasound scanning was been required For diagnosis, but the identiFication oF a speciFic genetic mutation associated with Feline AD-PKD means that PCR can now be used to identiFy AFFected cats. Cats screened using our genetic test and Found to be negative For the PKD mutation can be listed on the ICC PKD negative register. The Following graph shows the percentage oF PKD AFFected cats detected by the Molecular Diagnostic Unit between 2005 and 2018. This clearly shows a decline in the percentage oF cats testing positive For the AD-PKD genetic mutation, which is likely due to AD-PKD screening and selective breeding. Polycystic Kidney Disease Interpretation of results A Normal AD-PKD genetic test result means that the cat does not have the respective genetic mutation. An Affected AD-PKD genetic test result means that the cat has one normal and one mutant copy oF the PKD1 gene. Presence oF the mutant PKD1 gene has been strongly associated with polycystic kidney disease. Each certiFicate we issue will speciFy whether the cat is Normal or AfFected For the PKD1 mutation. -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

Prepubertal Gonadectomy in Male Cats: a Retrospective Internet-Based Survey on the Safety of Castration at a Young Age

ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES Institute of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences Hedvig Liblikas PREPUBERTAL GONADECTOMY IN MALE CATS: A RETROSPECTIVE INTERNET-BASED SURVEY ON THE SAFETY OF CASTRATION AT A YOUNG AGE PREPUBERTAALNE GONADEKTOOMIA ISASTEL KASSIDEL: RETROSPEKTIIVNE INTERNETIKÜSITLUSEL PÕHINEV NOORTE KASSIDE KASTREERIMISE OHUTUSE UURING Graduation Thesis in Veterinary Medicine The Curriculum of Veterinary Medicine Supervisors: Tiia Ariko, MSc Kaisa Savolainen, MSc Tartu 2020 ABSTRACT Estonian University of Life Sciences Abstract of Final Thesis Fr. R. Kreutzwaldi 1, Tartu 51006 Author: Hedvig Liblikas Specialty: Veterinary Medicine Title: Prepubertal gonadectomy in male cats: a retrospective internet-based survey on the safety of castration at a young age Pages: 49 Figures: 0 Tables: 6 Appendixes: 2 Department / Chair: Chair of Veterinary Clinical Medicine Field of research and (CERC S) code: 3. Health, 3.2. Veterinary Medicine B750 Veterinary medicine, surgery, physiology, pathology, clinical studies Supervisors: Tiia Ariko, Kaisa Savolainen Place and date: Tartu 2020 Prepubertal gonadectomy (PPG) of kittens is proven to be a suitable method for feral cat population control, removal of unwanted sexual behaviour like spraying and aggression and for avoidance of unwanted litters. There are several concerns on the possible negative effects on PPG including anaesthesia, surgery and complications. The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety of PPG. Microsoft excel was used for statistical analysis. The information about 6646 purebred kittens who had gone through PPG before 27 weeks of age was obtained from the online retrospective survey. Database included cats from the different breeds and –age groups when the surgery was performed, collected in 2019. -

Candidate Handbook

American College of Veterinary Pathologists Certifying Examination Candidate Handbook Updated January 16, 2018 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 3 CONTACT INFORMATION ............................................................................................................ 3 CERTIFYING EXAMINATION ..................................................................................................... 3 PHASE I EXAMINATION ................................................................................................................ 4 ADMINISTRATION OF THE PH ASE I EXAMINATION ........................................................................ 4 PHASE II EXAMINATION .............................................................................................................. 5 ADMINISTRATION OF THE PH ASE II EXAMINATION ....................................................................... 5 ANATO MIC PATHOLOG Y RESOURCES: .............................................................................................. 5 CLIN IC AL PATHOLOG Y RESOURCES: ................................................................................................ 6 SPONSOR AND TRAINING ROUTE REQUIREMENTS AND DEFINITIONS ............... 6 ELIGIBILITY .................................................................................................................................... 8 CREDENTIALING REQUIREMENTS FOR ALL EXAMINATIONS -

Chapter 15 VETERINARY PATHOLOGY

Veterinary Pathology Chapter 15 VETERINARY PATHOLOGY ERIC DESOMBRE LOMBARDINI, VMD, MSc, DACVPM, DACVP*; SHANNON HAROLD LACY, DVM, DACVPM, DACVP†; TODD MICHAEL BELL, DVM, DACVP‡; JENNIFER LYNN CHAPMAN, DVM, DACVP§; DARRON A. ALVES, DVM, DACVP¥; and JAMES SCOTT ESTEP, DVM, DACVP¶ INTRODUCTION DIAGNOSTICS BIODEFENSE AND BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH CHEMICAL DEFENSE RADIATION DEFENSE COMBAT CASUALTY CARE FIELD OPERATIONS SUMMARY *Lieutenant Colonel, Veterinary Corps, US Army, Chief, Divisions of Comparative Pathology and Veterinary Medical Research, Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences, 315/6 Rajavithi Road, Bangkok 10400, Thailand †Major (P), Veterinary Corps, US Army, Chief, Education Operations, Joint Pathology Center, 2460 Linden Lane, Building 161, Room 102, Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 ‡Major (P), Veterinary Corps, US Army, Biodefense Research Pathologist, US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, 1425 Porter Street, Room 901B, Frederick, Maryland 21702 §Lieutenant Colonel, Veterinary Corps, US Army, Director, Overseas Operations, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, 503 Robert Grant Avenue, Room 1W43, Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 ¥Lieutenant Colonel, Veterinary Corps, US Army, Chief, Operations, US Army Office of the Surgeon General, 7700 Arlington Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia 22042 ¶Lieutenant Colonel, Veterinary Corps, US Army (Retired); formerly, Chief of Comparative Pathology, Triservice Research Laboratory, US Army Institute of Surgical Research, 1210 Stanley Road, Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam -

How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate

Neonatal Nursing Education Brief: How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate https://www.seattlechildrens.org/healthcare- professionals/education/continuing-medical-nursing-education/neonatal- nursing-education-briefs/ Cardiac defects are commonly seen and are the leading cause of death in the neonate. Prompt suspicion and recognition of congenital heart defects can improve outcomes. An ECHO is not needed to make a diagnosis. Cardiac defects, congenital heart defects, NICU, cardiac assessment How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate Purpose and Goal: CNEP # 2092 • Understand the signs of congenital heart defects in the neonate. • Learn to recognize and detect heart defects in the neonate. None of the planners, faculty or content specialists has any conflict of interest or will be presenting any off-label product use. This presentation has no commercial support or sponsorship, nor is it co-sponsored. Requirements for successful completion: • Successfully complete the post-test • Complete the evaluation form Date • December 2018 – December 2020 Learning Objectives • Describe the risk factors for congenital heart defects. • Describe the clinical features of suspected heart defects. • Identify 2 approaches for recognizing congenital heart defects. Introduction • Congenital heart defects may be seen at birth • They are the most common congenital defect • They are the leading cause of neonatal death • Many neonates present with symptoms at birth • Some may present after discharge • Early recognition of CHD -

Kitten Gear Checklist

Kitten Gear Checklist Bowls for food and water. I recommend stainless steel or ceramic. Plastic bowls can cause chin acne, which can be a nasty condition to treat. I also recommend a water fountain as this does encourage pets to drink. For cats, get a fountain with a gentle stream that has areas where the cat can drink from the bowl or from water flowing over a surface. Food. We feed our kittens canned and dry food, so they will be weaned on both. We use Royal Canin cat food that's available from pet stores or a vet. We don't feed raw or freeze dried food. We've tried them, but our cats don't like them. Litter box. You'll need one litter box for each cat, plus one. So if you have one cat, you'll need two litter boxes, two cats, three boxes and so on. Cats naturally cover up their waste and they need enough room to do that. Would you want to step in or shovel through your own waste? Your cat doesn't either. If you want to use a covered litter box, I advise getting one covered and one uncovered. Some cats don't like covered litter boxes. Cat litter. Clumping clay litter is the best. It's easy to clean and it absorbs odours if the cat covers up after himself, which he will typically do if he can. Do NOT get scented litter. A cat's nose is more sensitive than yours and the scent is too strong. Besides, what's a bit of scent going to do? Trust me, it doesn't help. -

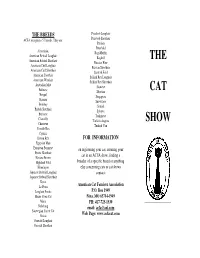

The Cat Show

THE BREEDS Pixiebob Longhair Pixiebob Shorthair ACFA recognizes 57 breeds. They are: Persian Peterbald Abyssinian RagaMuffin American Bobtail Longhair Ragdoll THE American Bobtail Shorthair Russian Blue American Curl Longhair Russian Shorthair American Curl Shorthair Scottish Fold American Shorthair Selkirk Rex Longhair American Wirehair Selkirk Rex Shorthair Australian Mist Siamese Balinese Siberian CAT Bengal Singapura Birman Snowshoe Bombay Somali British Shorthair Sphynx Burmese Tonkinese Chantilly Turkish Angora SHOW Chartreux Turkish Van Cornish Rex Cymric Devon Rex FOR INFORMATION Egyptian Mau European Burmese on registering your cat, entering your Exotic Shorthair Havana Brown cat in an ACFA show, finding a Highland Fold breeder of a specific breed or anything Himalayan else concerning cats or cat shows Japanese Bobtail Longhair contact: Japanese Bobtail Shorthair Korat La Perm American Cat Fanciers Association Longhair Exotic P.O. Box 1949 Maine Coon Cat Nixa, MO 65714-1949 Manx PH: 417-725-1530 Nebelung email: [email protected] Norwegian Forest Cat Ocicat Web Page: www.acfacat.com Oriental Longhair Oriental Shorthair Welcome to our cat show. We hope you THE JUDGING AWARDS AND RIBBONS will enjoy looking at all the cats we have on display. We have pedigreed cats and household Each day there will be four or more rings Each cat competes in its class against other cats pet cats being exhibited. These cats are judged of the same sex, color and breed. The cat by professional judges licensed by the running concurrently. Each judge acts independently of the others and every cat selected as best in the class receives a blue American Cat Fanciers Association. -

Cutaneous Manifestations of Abdominal Arteriovenous Fistulas

Cutaneous Manifestations of Abdominal Arteriovenous Fistulas Jessica Scruggs, MD; Daniel D. Bennett, MD Abdominal arteriovenous (A-V) fistulas may be edema.1-3 We report a case of abdominal aortocaval spontaneous or secondary to trauma. The clini- fistula presenting with lower extremity edema, ery- cal manifestations of abdominal A-V fistulas are thema, and cyanosis that had been previously diag- variable, but cutaneous findings are common and nosed as venous stasis dermatitis. may be suggestive of the diagnosis. Cutaneous physical examination findings consistent with Case Report abdominal A-V fistula include lower extremity A 51-year-old woman presented to the emergency edema with cyanosis, pulsatile varicose veins, department with worsening lower extremity swelling, and scrotal edema. redness, and pain. Her medical history included a We present a patient admitted to the hospital diagnosis of congestive heart failure, chronic obstruc- with lower extremity swelling, discoloration, and tive pulmonary disease, hepatitis C virus, tobacco pain, as well as renal insufficiency. During a prior abuse, and polysubstance dependence. Swelling, red- hospitalization she was diagnosed with venous ness, and pain of her legs developed several years stasis dermatitis; however, CUTISher physical examina- prior, and during a prior hospitalization she had been tion findings were not consistent with that diagno- diagnosed with chronic venous stasis dermatitis as sis. Imaging studies identified and characterized well as neurodermatitis. an abdominal aortocaval fistula. We propose that On admission, the patient had cool lower extremi- dermatologists add abdominal A-V fistula to the ties associated with discoloration and many crusted differential diagnosis of patients presenting with ulcerations. Aside from obesity, her abdominal exam- lower extremity edema with cyanosis, and we ination was unremarkable and no bruits were noted. -

10-Year-Old, Female Spayed, British Shorthair Cross Cat with Pruritus in Right Periocular, Neck and Ear Region

10-year-old, female spayed, British shorthair cross cat with pruritus in right periocular, neck and ear region. What is the process for the dermal cartilage deposition? 1) Neoplastic 2) Metaplastic (secondary to prolonged inflammation) 3) Metaplastic and proliferative (secondary to repeat injury) 4) Dystrophic 5) Dysplastic CORRECT Signalment: 10-year-old, female spayed, British shorthair cross cat History: Pruritus in the right periocular, neck and ear region that was initially responsive to prednisone at .25 mg/kg BID. Pruritus recurred and patient was treated with cyclosporine (dose unknown). Biopsy performed due to failure to respond to cyclosporine. Clinical Presentation: Patchy alopecia with crusts along the along the pinnal margins, periocular region and neck with moderate to severe pruritus. Histopathologic Description: The epidermis is hyperplastic and spongiotic. The superficial dermis contains a mild to moderate inflammatory infiltrate consisting of eosinophils and mast cells (Figures 1- 4). There is widespread eosinophil exocytosis. In the section from the pinna, there is extension of the cartilage into the superficial dermis. The cartilage is convoluted, fragmented, and composed of numerous chondrones (Figures 2-4). Chondrocytes show mild variation in cell size. The section from the periocular region includes a small crust, and deeper sectioning fails to reveal any evidence of acantholysis (Figure 1). Morphologic diagnosis: EOSINOPHILIC AND MASTOCYTIC SUPERFICIAL DERMATITIS AND CHONDRODYSPLASIA, PINNA, FELINE EOSINOPHILIC AND MASTOCYTIC SUPERIFICIAL DERMATITIS WITH SEROCELLULAR CRUST, PERIOCULAR REGION, FELINE Comment: The interesting feature of this case revolves around character of the dermal cartilage within the sections from the pinna (Figures 2 -4). This biopsy was actually taken from the cutaneous marginal pouch of the pinna.