Disguise As a Catalyst of Identity Confusion in Laurie King's Sherlockian Mary Russell Mysteries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beekeepers Apprentice: Or, on the Segregation of the Queen Free

FREE THE BEEKEEPERS APPRENTICE: OR, ON THE SEGREGATION OF THE QUEEN PDF Laurie R King | 356 pages | 27 May 2014 | Picador USA | 9781250055705 | English | United States The Beekeeper's Apprentice, or, on the Segregation of the Queen Summary & Study Guide Audible Premium Plus. Cancel anytime. It is and Mary Russell - Sherlock Holmes's brilliant apprentice, now an Oxford graduate with a degree in theology - is on the verge of acquiring a sizable inheritance. Independent at last, with a passion for divinity and detective work, her most baffling mystery may now involve Holmes and the burgeoning of a deeper affection between herself and the retired detective. By: Laurie R. The third book in the Mary Russell—Sherlock Holmes series. It is Mary Russell Holmes and her husband, the retired Sherlock Holmes, are enjoying the summer together on their Sussex estate when they The Beekeepers Apprentice: Or visited by an old friend, Miss Dorothy Ruskin, an archeologist just returned from Palestine. In the eerie wasteland of Dartmoor, Sherlock Holmes summons his devoted wife and partner, Mary Russell, from her studies at Oxford to aid the investigation of a death and some disturbing phenomena of a decidedly supernatural origin. Through the mists of the moor there have been sightings of a spectral coach made of bones carrying a woman long-ago accused of murdering her husband - and of a hound with a single glowing eye. Coming out of retirement, an aging Sherlock Holmes travels to Palestine with his year-old partner, Mary Russell. There, disguised as ragged Bedouins, they embark on a dangerous mission. -

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

Historical Mysteries UK

Gaslight Books Catalogue 3: Historical Mysteries set in the UK Email orders to [email protected] Mail: G.Lovett, PO Box 88, Erindale Centre, ACT 2903 All prices are in Australian dollars and are GST-free. Postage & insurance is extra at cost. Orders over $100 to $199 from this catalogue or combining any titles from any of our catalogues will be sent within Australia for a flat fee of $10. Orders over $200 will be sent post free within Australia. Payment can be made by bank transfer, PayPal or bank/personal cheque in Australian dollars. To order please email the catalogue item numbers and/or titles to Gaslight Books. Bank deposit/PayPal details will be supplied with invoice. Books are sent via Australia Post with tracking. However please let me know if you would like extra insurance cover. Thanks. Gayle Lovett ABN 30 925 379 292 THIS CATALOGUE features first editions of mysteries set in the United Kingdom roughly prior to World War II. Most books are from my own collection. I have listed any faults. A very common fault is browning of the paper used by one major publisher, which seems inevitable with most of their titles. Otherwise, unless stated, I would class most of the books as near fine in near fine dustcover and are first printings and not price-clipped. (Jan 27, 2015) ALEXANDER, BRUCE (Bruce Alexander Cook 1932-2003) Blind Justice: A Sir John Fielding Mystery (First Edition) 1994 $25 Hardcover Falsely charged with theft in 1768 London, thirteen-year-old Jeremy Proctor finds his only hope in Sir John Fielding, the founder of the Bow Street Runners police force, who recruits young Jeremy in his mission to fight crime. -

Writer's Guide to the World of Mary Russell

Information for the Writer of Mary Russell Fan Fiction Or What Every Writer needs to know about the world of Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes as written by Laurie R. King in what is known as The Kanon By: Alice “…the girl with the strawberry curls” **Spoiler Alert: This document covers all nine of the Russell books currently in print, and discloses information from the latest memoir, “The Language of Bees.” The Kanon BEEK – The Beekeeper’s Apprentice MREG – A Monstrous Regiment of Women LETT – A Letter of Mary MOOR – The Moor OJER – O Jerusalem JUST – Justice Hall GAME – The Game LOCK – Locked Rooms LANG – The Language of Bees GOTH – The God of the Hive Please note any references to the stories about Sherlock Holmes published by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (known as The Canon) will be in italics. The Time-line of the Books BEEK – Early April 1915 to August of 1919 when Holmes invites the recovering Russell to accompany him to France and Italy for six weeks, to return before the beginning of the Michaelmas Term in Oxford (late Sept.) MREG – December 26, 1920 to February 6, 1921 although the postscript takes us six to eight weeks later, and then several months after that with two conversations. LETT – August 14, 1923 to September 8, 1923 MOOR – No specific dates given but soon after LETT ends, so sometime the end of September or early October 1923 to early November 1923. We know that Russell and Holmes arrived back at the cottage on Nov. 5, 1923. OJER – From the final week of December 1918 until approx. -

Sherlock Holmes for Dummies

Index The Adventure of the Eleven Cuff-Buttons • Numerics • (Thierry), 249 221b Baker Street, 12, 159–162, 201–202, “The Adventure of the Empty House,” 301, 304–305 21, 48, 59, 213, 298 “The Adventure of the Engineer’s Thumb,” 20, 142 • A • “The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez,” 22, 301 “The Abbey Grange,” 22 “The Adventure of the Illustrious Client,” Abbey National, 162 24, 48, 194–195, 309 acting, Sherlock Holmes’s, 42. See also “The Adventure of the Lion’s Mane,” 24, 93 individual actors in roles “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone,” Adler, Irene (character), 96, 280, 298 24, 159 “The Adventure of Black Peter,” 22 “The Adventure of the Missing Three- “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Quarter,” 22 Milverton,” 22, 137, 267 “The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor,” “The Adventure of Shoscombe Old 20, 308 Place,” 25 “The Adventure of the Norwood “The Adventure of the Abbey Grange,” 22 Builder,” 21 “The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet,” “The Adventure of the Priory School,” 22 20, 141 “The Adventure of the Red Circle,” “The Adventure of the Blanched 23, 141, 188 Soldier,” 24, 92, 298 “The Adventure of the Reigate Squire,” 20 “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle,” “The Adventure of the Retired 19, 141, 315 Colourman,” 25 “The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington “The Adventure of the Second Stain,” 22, 78 Plans,” 23 “The Adventure of the Six Napoleons,” “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box,” 22, 73 20, 97, 138, 189, 212 “The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist,” “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches,” 21, 137, 140 20, 140 “The Adventure of the Speckled -

Olivia Votava Undergraduate Murder, Mystery, and Serial Magazines: the Evolution of Detective Stories to Tales of International Crime

Olivia Votava Undergraduate Murder, Mystery, and Serial Magazines: The Evolution of Detective Stories to Tales of International Crime My greatly adored collection of short stories, novels, and commentary began at my local library one day long ago when I picked out C is for Corpse to listen to on a long car journey. Not long after I began purchasing books from this series starting with A is for Alibi and eventually progressing to J is for Judgement. This was my introduction to the detective story, a fascinating genre that I can’t get enough of. Last semester I took Duke’s Detective Story class, and I must say I think I may be slightly obsessed with detective stories now. This class showed me the wide variety of crime fiction from traditional Golden Age classics and hard-boiled stories to the eventual incorporation of noir and crime dramas. A simple final assignment of writing our own murder mystery where we “killed” the professor turned into so much more, dialing up my interest in detective stories even further. I'm continuing to write more short stories, and I hope to one day submit them to Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and be published. To go from reading Ellery Queen, to learning about how Ellery Queen progressed the industry, to being inspired to publish in their magazine is an incredible journey that makes me want to read more detective novels in hopes that my storytelling abilities will greatly improve. Prior to my detective story class, I was most familiar with crime dramas often adapted to television (Rizzoli & Isles, Bones, Haven). -

A Mary Russell Companion

AA MMaarryy RRuusssseellll CCoommppaanniioonn Exploring the World of Laurie R. King’s Mary Russell/Sherlock Holmes Series elcome to the world of Mary Russell, one-time apprentice, long-time partner to Sherlock Holmes. What follows is an introduction to Russell’s memoirs, published under the name of Laurie R. King beginning with The Beekeeper’s Apprentice in 1994. We’ve added comments, excerpts, illuminating photos and an assortment of interesting links and extras. Some of them are fun, some of them are scholarly. Which only goes to prove that laughter and learning can go hand in hand. Enjoy! Laurie R. King Laurie R. King.com Mary Russell.com Contents INTRODUCTION ONE: Beginnings: Mary stumbles (literally) on Holmes (The Beekeepers Apprentice) TWO: Coming of Age: A Balancing Act (A Monstrous Regiment of Women) THREE: Mary Russell, Theologian (A Letter of Mary) FOUR: Russell & Holmes in Baskerville Country (The Moor) FIVE: Time and Place in Palestine (O Jerusalem) SIX: The Great War & the Long Week-end (Justice Hall) SEVEN: An Empire in Sunset—The Raj, Kipling’s Boy, & the Great Game (The Game) EIGHT: Loose Ends—Russell & Holmes in America (Locked Rooms) NINE: A Face from the Past (The Language of Bees) TEN: Russell & Holmes Meet a God (The God of the Hive) POSTSCRIPT One: Mary stumbles (literally) on Holmes Click cover for book page The Beekeeper‘s Apprentice: With Some Notes Upon the Segregation of the Queen (One of the Independent Mystery Booksellers Association’s 100 Best Novels of the Century) Mary Russell is what Sherlock Holmes would look like if Holmes, the Victorian detective, were a) a woman, b) of the Twentieth century, and c) interested in theology. -

Women Sleuths 20

Women Sleuths Bibliography Edition 20 January 2020 Brown Deer Public Library 5600 W. Bradley Road Brown Deer, WI 53223 1 MMMysteryMystery Murder Investigation Detective Evidence ClueClue…… She may be a police officer, a private detective, an office worker, a professor, an attorney, a nun, or even a librarian, but the woman sleuth is always tenacious and self-reliant. She may occasionally use her physical strength or a weapon in the course of her crime solving; more often, though, she uses her intelligence, her expertise in a specific area, and her understanding of human nature to reach a solution. The Women Sleuths Bibliography was first compiled by Linda Paulaskas, former South Milwaukee Library Director, and Cathy Morris-Nelson, former Brown Deer Library Director. Kelley Hinton, Reference Librarian at the Brown Deer Library, continued to revise and update the bibliography through the 13th Edition. Since then, updates have been made by Brown Deer Library volunteer and mystery enthusiast Paula Reiter. This is not a comprehensive bibliography, but rather a compilation of current series, which feature a woman sleuth. Most of the titles in this bibliography can be found arranged alphabetically by author at the Brown Deer Public Library. ___ We have added lines in front of each title, so you might keep track of the books and authors you read. We have also included author website addresses and unique features found on the sites. This symbol indicates a series new to the twentieth edition. The cover photo was found on the Paumelia Flickr Creative Commons photostream. Thank you for sharing your photo! Kimura, Yumi. -

The Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes Ebook

THE MYSTERIES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sir Arthur Conan Doyle,J. Conway | 95 pages | 12 Apr 1982 | Random House USA Inc | 9780394850863 | English | New York, United States The Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes PDF Book As the story opens, the Prince is engaged to another. Despite Holmes's remarkable reasoning abilities, Conan Doyle still paints him as fallible in this regard this being a central theme of " The Yellow Face ". Plot Keywords. Only one other adventure, " The Adventure of the Lion's Mane ", takes place during the detective's retirement. Hidden Tiger. My Sherlock Holmes. Eudoria has taught Enola everything she knows, from hand-to-hand combat, to discovering cyphers and anagrams, to history, politics, literature, and home tennis. Watson describes him as. Redmond, Christopher Visit our What to Watch page. Holmes is an adept bare-knuckle fighter; "The " Gloria Scott " mentions that Holmes boxed while at university. He disliked and distrusted the sex, but he was always a chivalrous opponent". For the one and only time I caught a glimpse of a great heart as well as of a great brain. The detective believes that the mind has a finite capacity for information storage, and learning useless things reduces one's ability to learn useful things. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex. Online quotes will allow policyholders the chance to discover multiple insurance companies and check their prices. Free Sherlock!. Retrieved 4 January An especially influential pastiche was Nicholas Meyer 's The Seven-Per-Cent Solution , a New York Times bestselling novel made into the film of the same name in which Holmes's cocaine addiction has progressed to the point of endangering his career. -

Misadventures Exhibit Catalog (296.2Kb Application/Pdf)

AN EXHIBITION OF ITEMS FROM THE SHERLOCK HOLMES COLLECTIONS JUNE 13 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2016 ELMER L. ANDERSEN LIBRARY GALLERY UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA—WEST BANK CAMPUS ST 222 21 AVENUE SOUTH MINNEAPOLIS, MN 55455 THE MISADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES This exhibit is inspired by a book of the same title published in 1944 and edited by Ellery Queen. Both book & exhibit celebrate an ever-expanding universe of Holmesian parodies & pastiches fashioned by a broad spectrum of creative people in a variety of formats & languages. We hope you enjoy this “roomy” stroll through a world that began in Victorian England & is now found in cyberspace. Welcome to our little Sherlockian misadventure! ELLERY QUEEN ON PARODY & PASTICHE “As a general rule writers of pastiches retain the sacred and inviolate form Sherlock Holmes and rightfully, since a pastiche is a serious and sincere imitation in the exact manner of the original author. But writers of parodies, which are humorous or satirical take-offs, have no such reverent scruples. They usually strive for the weirdest possible distortions and it must be admitted that many highly ingenious travesties have been conceived. Fortunately or unfortunately, depending on how much of a purist one is, the name Sherlock Holmes is peculiarly susceptible to the twistings and misshapenings of burlesque-minded authors.” THE “BIG BANG” Since 1887, in almost cosmic fashion, nearly every medium & format has been employed in creating Sherlockian parodies & pastiches. Starting from the original sixty canonical tales, authors & artists of every stripe—detective story writers, famous literary figures, humorists, devotees & fans—created a “host of aliases” for Mr. -

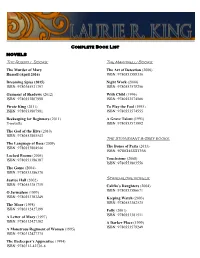

Complete Book List

Complete Book List NOVELS The Russell Books: The Martinelli Books: The Murder of Mary The Art of Detection (2006) Russell (April 2016) ISBN: 9780553588330 Dreaming Spies (2015) Night Work (2000) ISBN: 9780345531797 ISBN: 9780553578256 Garment of Shadows (2012) With Child (1996) ISBN: 9780553807998 ISBN: 9780553574586 Pirate King (2011) To Play the Fool (1995) ISBN: 9780553807981 ISBN: 9780553574555 Beekeeping for Beginners (2011) A Grave Talent (1993) E-novella ISBN: 9780553573992 The God of the Hive (2010) ISBN: 9780553805543 The Stuyvesant & Grey books: The Language of Bees (2009) ISBN: 9780553804546 The Bones of Paris (2013) ISBN: 9780345531766 Locked Rooms (2005) ISBN: 9780553386387 Touchstone (2008) ISBN: 9780553803556 The Game (2004) ISBN: 9780553386370 Stand-alone novels: Justice Hall (2002) ISBN: 9780553381719 Califia’s Daughters (2004) ISBN: 9780553586671 O Jerusalem (1999) ISBN: 9780553383249 Keeping Watch (2003) ISBN: 9780553382525 The Moor (1998) ISBN: 9780312427399 Folly (2001) A Letter of Mary (1997) ISBN: 9780553381511 ISBN: 9780312427382 A Darker Place (1999) ISBN: 9780553578249 A Monstrous Regiment of Women (1995) ISBN: 9780312427375 The Beekeeper’s Apprentice (1994) ISBN: 9780312-42736-8 Complete Book List Anthology Contributions NONFICTION Co-editor, In the Company of Sherlock Holmes, with Not in Kansas Anymore, TOTO, co-authored with Leslie S. Klinger, Pegasus (2014) ISBN: 1605986585 Barbara Peters (2015), Poisoned Pen Press Co-editor, A Study in Sherlock, with Leslie S. Klinger, Crime & Thriller Writing: A Writers’ & Artists’ Random House & Poisoned Pen Press (2011) ISBN: Companion, co-authored with Michelle Spring (2013) 9780345529930 ISBN: 9781472523938 “Hellbender” in Down These Strange Streets, ed. My Bookstore, ed. Ronald Rice, Black Dog & George R. R. Martin & Gardner Dozois, Ace Hardcover Levanthal (2012) (2011) ISBN: 9780441020744 ISBN: 9781579129101 Introduction, The Grand Game, Volume 1, The Baker Books to Die For, ed. -

Information for the Writer of Mary Russell Fan Fiction Or What Every Writer Needs to Know About the World of Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes As Written by Laurie R

Information for the Writer of Mary Russell Fan Fiction Or What Every Writer needs to know about the world of Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes as written by Laurie R. King in what is known as The Kanon By: Alice “…the girl with the strawberry curls” **Spoiler Alert: This document covers all eleven of the Russell books currently in print. The Kanon BEEK – The Beekeeper’s Apprentice ** MREG – A Monstrous Regiment of Women LETT – A Letter of Mary MOOR – The Moor OJER – O Jerusalem JUST – Justice Hall GAME – The Game LOCK – Locked Rooms LANG – The Language of Bees GOTH – The God of the Hive PIRA – The Pirate King GARM – Garment of Shadows **B4B – Beekeeping for Beginners, an e-novella (Told from Holmes’ POV this short story covers the meeting and early weeks of the friendship between Holmes and Russell) Please note any references to the stories about Sherlock Holmes published by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (known as The Canon) will be in italics. The Time-line of the Books BEEK – Early April 1915 to August of 1919 when Holmes invites the recovering Russell to accompany him to France and Italy for six weeks, to return before the beginning of the Michaelmas Term in Oxford (late Sept.) MREG – December 26, 1920 to February 6, 1921 although the postscript takes us six to eight weeks later, and then several months after that with two conversations. LETT – August 14, 1923 to September 8, 1923 MOOR – No specific dates given but soon after LETT ends, so sometime the end of September or early October 1923 to early November 1923.