Issue 2 Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 54, No. 4, October 14, 2003 University of Michigan Law School

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Res Gestae Law School History and Publications 2003 Vol. 54, No. 4, October 14, 2003 University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.umich.edu/res_gestae Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation University of Michigan Law School, "Vol. 54, No. 4, October 14, 2003" (2003). Res Gestae. Paper 123. http://repository.law.umich.edu/res_gestae/123 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School History and Publications at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Res Gestae by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT NEWSPAPER oF 1HE UNIVERSITY oF MICHIGAN LAw ScHOOL October 14, 2003 Vol. 54 No.4 Downloaders Beware! Record Industry Lawuits Are Indeed 2 Legit 2 Quit By Sharon Ceresnie it become clear what the state of the law is on file sharing. And while the RIAA has for the Intellectual Property Student ost of us have heard about only filed 261 suits as of September 8, Association's (IPSA) guest speaker the lawsuits that the 2003, many of us have begun to realize Andrew P. Bridges on "Are the RIAA Recording Industry that the next suit filed could easily be Lawsuits Legit?" After speaking during Association of America (RIAA) has against one of our friends or even lunchtime, Bridges also visited Professor brought against peer-to-peer file sharers. -

Ferrante Winery

Open Noon to past sunset OPEN Sunday-ThursdaySun-Thurs 12-6 ALL and Midnight on Fridays YEAR! & Saturdays Visit us for your next Vacation or Get-Away! Four Rooms Complete with Private Hot Tubs 4573 Rt. 307 East, Harpersfi eld, Ohio Three Rooms at $80 & Outdoor Patios 440.415.0661 One Suite at $120 www.bucciavineyard.com JOIN US FOR LIVE ENTERTAINMENT ALL Live Entertainment Fridays & Saturdays! WEEKEND! Appetizers & Full Entree www.debonne.com Menu See Back Cover See Back Cover For Full Info For Full Info www.grandrivercellars.com 2 www.northcoastvoice.com • (440) 415-0999 June 10 - 24, 2015 Pairings hires new Executive Chef Michael Lorah Pairings, Ohio’s Wine and Culinary Center, is extremely pleased that Michael H. Lorah will be joining the facility as Executive Chef. With over fi fteen years of culinary experience, Chef Michael brings a rich background of creating delicious signature dishes as well as managing boutique and larger restaurants. “Needless to say, hiring Chef Michael is the culmination of six years of hard work, and we are so glad to see it come to fruition,” said Mark Winchell, president of the Pairings board of Connect 534 was designed around trustees. “He is extremely talented. We knew almost immediately that he was the one to take creating and marketing new events this new position and grow it.” along State Route 534; The City of “I am not defi ned by anything right now as this is a new position,” said Chef Michael, Geneva, Geneva Township, Geneva- “which is very exciting. It is a blank slate. -

Barenaked Ladies Are Stunt Men

Ed Robertson, Steven Page, Tyler Stewart, Jim Creeggan, Kevin Hearn of Bare Naked Ladies REPRISE RECORDS BARENAKED LADIES ARE STUNT MEN That headline shouldn't seem too shocking, since Barenaked Ladies have become ing about how they'd sung the national anthem at that afternoon's Philladelphia Flyers one of the biggest success stories of the rock world this year. I first heard of them years game and this somehow lead to a medley of every Hall and Oates song they could ago when they sang an anti-racism song on a Fox Saturday morning PSA where remember. Earlier, they rapped about Scooby-Doo and cheesesteaks completely off the _ singer/guitarist Ed Robertson was painted green as a space alien. top of their heads. The setlist was made up mostly of songs from Stunt. The crowd joey Odorisio Their 1992 debut album Gordon was a huge hit in their native went nuts for "One Week" and knew every word. Canada, and had a few college hits here in the U.S. with "Be My The band's silliness continued throughout the show. A guy was lowered from the SruFWRIIER ------- Yoko Ono" and "If I Had $1,000,000." Two years ago, Barenaked rafters during "Shoebox" to merely playa tambourine, and a giant flashing "BNL" sign Ladies (BNL for short) had their biggest U.S. radio hit with ''The came down behind the band' at one point, leading to jokes about KISS. Robertson got Old Apartment" and another one last year with a live version of Gordon s "Brian a security guard to play "Smoke On the Water" with him, then the whole band played Wilson." However, this summer they exploded with "One Week" from their fourth stu some of the song, singing "meet the security guard!" "The Old Apartment" was anoth dio album Stunt and played on the H.O.R.D.E. -

May to August 2018 Y a M

May to August 2018 y a M 1 1 , d y o r k c A y p p o P MEDIA PARTNER www.thequeenshall.net +44 (0)131 668 2019 Clerk Street, Edinburgh EH8 9JG Booking Tickets Online www.thequeenshall.net Over the phone +44 (0)131 668 2019 Mon –Sat 10am –5pm or until one hour before start on show nights In person 85 –89 Clerk Street, Edinburgh EH8 9JG Mo n–Sat 10a m–5.15pm or until 15 mins after start on show nights Edinburgh International Festival Tickets for EIF cannot be bought through our sales channels until the Festival starts. Until then, please visit: eif.co.uk | +44 (0)131 473 2000 | Hub Tickets, The Hub, Castlehill, Edinburgh EH1 2NE Transaction charge: A £1 fee is charged on all bookings made online and over the phone. This is per booking, not per ticket and helps support the running of our Box Office. Booking fees Some shows incur a booking fee ( bf ), which is a per ticket charge for all bookings (phone, online, in person) Postage Tickets can be posted out to you second class up to seven days before the event for a cost of £1.00 per transaction. Alternatively you can collect tickets free of charge from the Box Office during opening hours. Concessions Concessionary priced tickets are available where indicated. If you book online, please bring proof of eligibility with you to the event. Doors open /start times For most events, the time shown is when the artist will begin their performance. Where we don't have this information in advance, a 'doors open' time is given, with more precise details available on our social media channels, website and via the Box Office on the day of the event. -

Take on Me.Mid a Kind of Magic.Mid A

50_cent_-_in_da_club.mid 60_on.mid 74-75 by THE CONNELLS.mid 99 Red Balloons-C68.mid A Ha - Take on me.mid A kind of magic.mid A Little Help From My Friends by The Beatles.mid A Little Respect By Erasure.mid A whiter shade of pale.mid a_Groovy_Kind_of_Love1-F100.mid a_little_bit_me_a_little_bit_you1-F137.mid A_Message_to_Rudy_by_THE_SPECIALS.mid Abba - Dancing queen.mid Abba - Fernando.mid Abba - I Have A Dream.mid Abba - Money money money.mid Abba - Super Trouper.mid Abba - Take A Chance On Me.mid Abba - Thank You For The Music.mid Abba Teens - Mamma Mia .mid Acdc - Highway To Hell.mid achy_breaky_heart1-A120.mid Addicted To Love by Robert Palmer.mid aeroplane.mid Aerosmith - I dont want to miss a thing.mid Against all odds.mid against_all_odds1-B65.mid aint_no_mountain_high_enough.mid aint_no_sunshine1-C76.mid aladdin1-C128.mid Alanis Morissette - Hand In My Pocket.mid Alanis Morissette - Head Over Feet.mid Alanis Morissette - Ironic.mid Alanis Morissette - You Oughta Know.mid Alannah Miles - Black velvet.mid Alice Cooper - Poison.mid ALIVE_AND_KICKING_Jim_Kerr_Charles_Burchill_Michael_MacNeil.mid aliveand.mid All Along the Watchtower by Jimi Hendrix.mid All apologies.mid All You Need Is Love THE BEATLES.mid all_I_Wanna_Do_Is_Have_Some_Fun1-G122-Sheryl_Crow.mid all_you_need_is_love1-C102.mid allgod.mid allnite.mid always_a_woman to me1- Billy Joel-Eb53.mid always_something_there_to_remind_me1-G148-harp.mid Amazing Grace MM GM.mid Amazing Grace.mid American Pie DON MCLEAN.mid Andrew Lloyd Webber - Jesus Christ Superstar.mid angels1-G100.mid -

PETER and RAYMOND QUIZ (Answers Below)

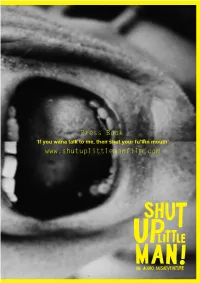

r Technical informa unning time: 85 mins | SYNOPSIS LONGER SYNOPSIS When two friends he most important audio recording released tape-recorded the in the nineties wasn’t a collection of songs fights of their by a self-tortured alternative star. The most violently noisy important recording released in the grunge neighbours, era was entitled SHUT UP LITTLE MAN! It was T ion they accidentally a covert audio recording of two older drunken f created one of the men living in a small flat in San Francisco, ormat: world’s first ‘viral’ who spent their available free time yelling, pop-culture screaming, hitting and generally abusing sensations. each other. h D Exploring the blurred | boundaries between he phenomenon began in 1987 when Eddie r privacy, art and Mitch (two young punks from the Mid atio: 1.78 and exploitation, West), moved next door to Peter Haskett Shut Up Little Man! (a flamboyant gay man), and Raymond Huffman An Audio (a raging homophobe). This ultimate odd- Misadventure couple hated each other with raging abandon, | is a darkly hilarious and through the paper-thin walls their Sound: Dolby Digital Stereo FILMLAB presents modern fable. alcohol-fuelled rants terrorised Eddie and a CLOSER production Mitch. Fearing for their lives they began to in association with the SOUTH AUSTRALIAN FILM CORPORATION tape record evidence of the insane goings and ADELAIDE FILM FESTIVAL on from next door. AUSTRALIA/NZ SALES TECHNICAL n recording Pete and Ray’s unique NICK BATZIAS [email protected] INFORmatION dialogue, the boys accidentally created one of the world’s first ‘viral’pop-culture US SALES Running time: 90 mins sensations. -

Page 1 TEACHER, TEACHER .38 SPECIAL I GO BLIND 54-40

Page 1 TEACHER, TEACHER .38 SPECIAL I GO BLIND 54-40 OCEAN PEARL 54-40 Make Me Do) ANYTHING YOU WANT A FOOT IN COLD WATER HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE HEAD OVER FEET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE THANK YOU ALANIS MORISSETTE UNINVITED ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU LEARN ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALANIS MORISSETTE BLACK VELVET ALANNAH MYLES LOVE IS ALANNAH MYLES LOVER OF MINE ALANNAH MYLES SONG INSTEAD OF A KISS ALANNAH MYLES STILL GOT THIS THING ALANNAH MYLES FANTASY ALDO NOVA MORE THAN WORDS CAN SAY ALIAS HELLO HURRAY ALICE COOPER BIRMINGHAM AMANDA MARSHALL DARK HORSE AMANDA MARSHALL FALL FROM GRACE AMANDA MARSHALL LET IT RAIN AMANDA MARSHALL BABY I LOVE YOU ANDY KIM BE MY BABY ANDY KIM HOW'D WE EVER GET THIS WAY? ANDY KIM I FORGOT TO MENTION ANDY KIM ROCK ME GENTLY ANDY KIM SHOOT 'EM UP BABY ANDY KIM BAD SIDE OF THE MOON APRIL WINE ENOUGH IS ENOUGH APRIL WINE I WOULDN'T WANT TO LOSE YOUR LOVE APRIL WINE I'M ON FIRE FOR YOU BABY APRIL WINE JUST BETWEEN YOU AND ME APRIL WINE LIKE A LOVER, LIKE A SONG APRIL WINE OOWATANITE APRIL WINE ROCK AND ROLL IS A VICIOUS GAME APRIL WINE ROLLER APRIL WINE SAY HELLO APRIL WINE SIGN OF THE GYPSY QUEEN APRIL WINE TONITE IS A WONDERFUL TIME APRIL WINE YOU COULD HAVE BEEN A LADY APRIL WINE YOU WON'T DANCE WITH ME APRIL WINE BLUE COLLAR BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE GIMME YOUR MONEY PLEASE BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE HEY YOU BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE LET IT RIDE BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE Page 2 LOOKIN' OUT FOR #1 BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE ROLL ON DOWN THE HIGHWAY BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE TAKIN' -

A Long Way to the Top If You Wanna Rock and Roll ADAMS, BRYAN

311 - Amber AC/DC- A Long Way To The Top If You Wanna ADAMS, BRYAN- Cuts Like a Knife, Straight from the Rock and Roll Heart, Heaven, Summer of 69 ALDEAN, JASON - Straight from the Heart/Heaven ADAMS, RYAN - Come Pick Me Up, New York, Two, ALABAMA/FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE - I'm In A ALICE IN CHAINS- Nutshell When The Stars Go Blue (with Tim McGraw) Hurry ALLMAN BROTHERS - Melissa, Ramblin'Man, Soulshine, ALLMAN, GREGG - I'm No Angel AMERICA- Horse with No Name, Sister Golden Hair, Ain't Wasting Time No More, Midnight Rider, One Way Ventura Highway Out, Seven Turns, Back Where It All Begins ANDERSON, JOHN- Seminole Wind ANIMALS- House of the Rising Sun ARMSTRONG, LOUIE - Wonderful World ASIA - Heat of the Moment AUDIOSLAVE - I Am The Highway AVETT BROTHERS - Head Full Of Doubt, I And Love And You BAD COMPANY- Bad Company, Feel Like Making Love, BAD FINGER - No Matter What THE BAND- Long Black Veil, The Weight, Night They Shooting Star Drove Old Dixie Down, Up On Cripple Creek, It Makes No Difference, Across The Great Divide BAND OF HORSES - Is There A Ghost, No Ones Gonna BARENAKED LADIES- The Old Apartment, BEACH BOYS - Wouldn't It Be Nice Love You Pinch Me BEATLES- 8 Days A Week, Across the Universe, Ballad of BECK - Jackass, Blue Moon, Nobody's Fault But BEE GEES - 1941 Mining Disaster, Massachusetts, To John and Yoko, Hide Your Love Away, I Feel Fine, In My My Own Love Somebody Life, I've Just Seen A Face, Let It Be, Norwegian Wood, She Came Thru Bathroom Window, She's A Woman, Something, Yesterday, Rocky Raccoon, Run For Your Life, Things -

You Can Live in an Apartment-Dorothy Duncan

YOU CAN LIVE IN AN APARTMENT- DOROTHY DUNCAN This is a reproduction of a book from the McGill University Library collection. Title: You can live in an apartment Author: Duncan, Dorothy Publisher, year: New York ; Toronto : Farrar & Rinehart, c1939 The pages were digitized as they were. The original book may have contained pages with poor print. Marks, notations, and other marginalia present in the original volume may also appear. For wider or heavier books, a slight curvature to the text on the inside of pages may be noticeable. ISBN of reproduction: 978-1-77096-107-4 This reproduction is intended for personal use only, and may not be reproduced, re-published, or re-distributed commercially. For further information on permission regarding the use of this reproduction contact McGill University Library. McGill University Library www.mcgill.ca/library YOU CAN LIVE IN AN APARTMENT LZJ I i i .i ' j i i t~ YOU CAN LIVE IN AN APARTMENT YOU CAN LIVE IN AN APARTMENT YOU (AN LIVE IN AN APARTMENT YOU (AN LIVE IN AN APARTMENT YOU (AN LIVE IN AN APARTMENT YOU (AN LIVE IN AN APARTMENT ' . » ,—i ,—i . i , J r-L- '.• i'i: • ivi' ' ; //DOROTHY DUNCAN r -T-^-r^n—i—r I II i Dacriratiohs hfr Dniglas Milliter | 1 ' FARRAR & RINEHARTlnc. NEW YORK TORONTO COPYRIGHT, 1939, BY DOROTHY DUNCAN MAC LENNAN PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY J. J. LITTLE AND IVES COMPANY, NEW YORK ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CONTENTS A WORD ASIDE, FIRST vii I. THE HUNTING SEASON . two expo sures, with a view 3 II. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Ladies and Gentlemen: Barenaked Ladies and the Persuasions Barenaked Ladies Join Forces with "Kings of a Cappella" for New LP out April 14, 2017

http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/ladies-and-gentlemen-barenaked-ladies-and-the- persuasions-300418473.html Ladies and Gentlemen: Barenaked Ladies and The Persuasions Barenaked Ladies join forces with "Kings of a Cappella" for new LP out April 14, 2017 Available for pre-order Friday March 10 News provided by Barenaked Ladies 06 Mar, 2017, 11:59 ET LOS ANGELES, March 6, 2017 /PRNewswire/ -- Barenaked Ladies have announced a very special collaboration with the legendary "Kings of A Cappella" titled, Ladies And Gentlemen: Barenaked Ladies And The Persuasions to be released April 14, 2017. Produced by Gavin Brown, the album features 14 tracks re-imagined BNL's award-winning catalogue and the classic 'Good Times.' BNL recorded the album live off the floor with The Persuasions last Fall at Noble Street Studios in Toronto. Ladies And Gentlemen: Barenaked Ladies And The Persuasions is available to pre-order on iTunes on March 10. Album and bundles featuring exclusive merchandise of Barenaked Ladies and The Persuasions will also be available worldwide through PledgeMusic. Each pre- order includes four instant-grat downloads of "The Old Apartment," "Odds Are," "Keepin' It Real," and "Don't Shuffle Me Back." Sessions X Trailer - Barenaked Ladies & The Persuasions New Album Out April 14 - Ladies & Gentlemen: Barenaked Ladies and The Persuasions New Album Out April 14 - Ladies & Gentlemen: Barenaked Ladies and The Persuasions The video streaming app Sessions X filmed the entire session and will feature full-length performances, interviews, and behind the scenes moments. Sessions X will launch their BNL content on Wednesday, March 22. WATCH + SHARE SESSIONS X TEASER TRAILER HERE The seed for Ladies and Gentlemen: Barenaked Ladies & The Persuasions was planted when Kevin Hearn befriended The Persuasions at Lou Reed's memorial held at the legendary Apollo Theatre in 2013. -

Steven Page | Mental Health Advocate | Canadian

905.831.0404 [email protected] http://www.kmprod.com Canadian Music Icon | Mental Health Advocate http://www.kmprod.com/speakers/speaker-steven-page Bio Steven Page is a natural in front of a crowd. Having shot to international fame as the co-founder of The Barenaked Ladies, Page now boasts an impressive solo career, where he continues to showcase his creative genius. A witty, endearing, and searingly honest speaker, Page continues to earn his rightful place in our national conversation. Page spent over two decades with The Barenaked Ladies, writing and co-writing hit songs such as “The Old Apartment,” “If I Had $1000000,” and “Brian Wilson,” among dozens of others. Along the way, the band earned accolades from all over the world, sold millions of albums, received two Billboard Awards, and six Juno Awards. In 2018, the band, along with Page, were Inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame and the JUNO Awards Hall of Fame. As an independent artist, Page has released three solo albums, The Vanity Project, Page One, and Heal Thyself Pt. 1: Instinct. Page has also collaborated on two albums and has tour with Toronto’s eclectic Art of Time Ensemble; has written six theatrical scores for the Stratford Festival; and is currently working on a musical with Governor General’s Award winner playwright Daniel McIvor. In addition, Page has also spoken at TEDx Toronto, and traveled North America as host of TV’s The Illegal Eater. Topics VIRTUAL: Songs & Stories from Isolation [morelink] KEYNOTES (all are also available virtually) Promoting Mental Health Everywhere [morelink] A Life in Arts & Culture For more information on Steve Page's speaking presentations, speaking schedule, fees & booking Steve Page, contact us.