Rethinking Enlargement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Introduction: Britain and Germany in the European Union of the Twenty-First Century

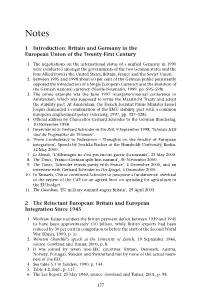

Notes 1 Introduction: Britain and Germany in the European Union of the Twenty-First Century 1. The negotiations on the international status of a unified Germany in 1990 were conducted amongst the governments of the two German states and the four Allied Powers the United States, Britain, France and the Soviet Union. 2. Between 1995 and 1998 about 60 per cent of the German public persistently opposed the introduction of a Single European Currency and the abolition of the German national currency (Noelle-Neumann, 1999, pp. 595–598). 3. The prime example was the June 1997 intergovernmental conference in Amsterdam, which was supposed to revise the Maastricht Treaty and adopt the stability pact. At Amsterdam, the French Socialist Prime Minister Lionel Jospin demanded a combination of the EMU stability pact with a common European employment policy (Gierieng, 1997, pp. 327–328). 4. Official address by Chancellor Gerhard Schröder to the German Bundestag, 10 November 1998. 5. Interview with Gerhard Schröder in Die Zeit, 9 September 1998, ‘Schröder:Jetzt sind die Pragmatiker die Visionäre’. 6. ‘From Confederacy to Federation – Thoughts on the finality of European integration’, Speech by Joschka Fischer at the Humboldt University, Berlin, 12 May 2000. 7. Le Monde, ‘L’Allemagne ne s’est pas encore guerie du nazisme’, 23 May 2000. 8. The Times, ‘Franco-German split hits summit’, 30 November 2000. 9. The Times, ‘Schröder rejects parity with France’, 4 December 2000, and an interview with Gerhard Schröder in Der Spiegel, 4 December 2000. 10. In Brussels, Chirac convinced Schröder to postpone a fundamental overhaul of the system of the CAP for an agreed limit on spending for agriculture in the EU budget. -

Biographies of Participants

Biographies of Participants Annual Colloquium on Fundamental Rights Media Pluralism and Democracy 26-27 November 2018 Justice and Consumers The biographies were sent by the participants. The European Commission is not responsible for the content. ACHEN Christopher H. Chris Achen holds the Roger Williams Straus Chair of Social Sciences at Princeton University. His primary research interests are public opinion, elections, and the realities of democratic politics. He is the author or co-author of six books, including Democracy for Realists (with Larry Bartels) in 2016, which has received widespread discussion and several awards. He has also published many articles. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and has received fellowships from the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, the National Science Foundation, and Princeton's Center for the Study of Democratic Politics. He was the founding president of the Political Methodology Society, and he received the first career achievement award from The Political Methodology Section of The American Political Science Association in 2007. He has served on the top social science board at the American National Science Foundation, and he was the chair of the national Council for the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) from 2013-2015. He is also the recipient of awards from the University of Michigan for lifetime achievement in training graduate students and from Princeton University for graduate student mentoring. AFANASJEVA Sonja Sonja Afanasjeva is policy officer in the Secretariat of the Young European Federalists (JEF Europe). Working closely with the Executive Board, she carries out advocacy work towards the European institutions and civil society, in Brussels and beyond, in order to further promote the idea of a free, united and democratic Europe. -

St Antony's College Record 2012

1 ST ANTONY’S COLLEGE RECORD 2012 - 2013 2 CONTENTS 1 – Overview of the College The College................................................................................................................ 3 The Fellowship.......................................................................................................... 5 The Staff.................................................................................................................... 12 2 – College Affairs From the Warden....................................................................................................... 15 From the Bursar......................................................................................................... 17 The Graduate Common Room................................................................................... 20 The Library................................................................................................................ 24 The St Antony’s/Palgrave Series............................................................................... 25 3 – Teaching and Research African Studies.......................................................................................................... 26 Asian Studies............................................................................................................. 33 European Studies....................................................................................................... 37 Latin American Studies............................................................................................ -

Agriculture for the the Figures Mask Big Variations Among OECD OECD’S Future

CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN REFORM THE FUTURE OF EUROPEAN AGRICULTURE Julie Wolf about the CER The Centre for European Reform is a think-tank devoted to improving the quality of the debate on the European Union. It is a forum for people with ideas from Britain and across the contintent to discuss the many social, political and economic challenges facing Europe. It seeks to work with similar bodies in other European countries, North America and elsewhere in the world. The CER is pro-European but not uncritical. It regards European integration as largely beneficial but recognises that in many respects the Union does not The future of work well. The CER therefore aims to promote new ideas for reforming the European Union. ★ Director: CHARLES GRANT European ADVISORY BOARD PERCY BARNEVIK................................................................................... Chairman, AstraZeneca CARL BILDT................................................................................. Former Swedish Prime Minister agriculture ANTONIO BORGES................................................................................ Former Dean of INSEAD NICK BUTLER (CHAIR)................................. Group Vice President for Policy Development, BP p.l.c. LORD DAHRENDORF ............... Former Warden of St Antony’s College, Oxford & EU Commissioner VERNON ELLIS....................................................................... International Chairman, Accenture JOHN GRAY.......................................................................... Professor of European -

Crowded out by Economic Focus

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Grabbe, Heather; Meyer, Henning; Valiante, Diego Article — Published Version Citizens' Europe: Crowded out by economic focus Intereconomics Suggested Citation: Grabbe, Heather; Meyer, Henning; Valiante, Diego (2012) : Citizens' Europe: Crowded out by economic focus, Intereconomics, ISSN 1613-964X, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 47, Iss. 5, pp. 268-281, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10272-012-0428-5 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/106765 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu DOI: 10.1007/s10272-012-0428-5 Forum Citizens’ Europe: Crowded Out by Economic Focus Over the last ten years the European unifi cation project seemed to rely overwhelmingly on progress in economic terms. -

The President's Annual Report on 2014

THE PRESIDENT’S ANNUAL REPORT ON 2014 The President’s Annual Report on 2014 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE REPORT ON CALENDAR YEAR 2014, PUBLISHED IN SPRING 2015 PUBLISHED IN APRIL 2015 BY THE EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE © EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, 2015 The European Commission supports the EUI through the European Union budget. This publication reflects the views only of the author(s), and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 PART 1. Reports on Academic Activities 10 The Graduate Programme 11 Economics 12 History and Civilization 17 Law 23 -Academy of European Law 31 Political and Social Sciences 33 Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies 39 Max Weber Programme for Postdoctoral Studies 48 Historical Archives of the European Union 54 Library and Institutional Repository (Cadmus) 56 Report on Publications 59 Academic Events - State of the Union 2014 60 Academic Events 2014 63 PART 2. Reports on Services 78 PART 3. The EUI in Numbers 88 PART 4. EUI Governance 101 PART 5. Annexes 108 Annex 1: Framework Agreement, European Parliament 109 Annex 2: Framework Agreement, European Court of Justice 116 Annex 3: Framework Agreement, College of Europe 119 Annex 4: Teaching Agreement, University of Florence 121 LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES Figure 1 Number of Applicants to MWF by Geographic Area 49 Figure 2 Applications for Max Weber and Jean Monnet Fellowship Programmes (2005-2014) 49 Figure 3 MWF Applications across Thematic Groups, 2014 49 Figure