The Generative Potential of Tensions Within Belgian Agroecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carte Hydrogéologique De Nobressart - Attert NOBRESSART - ATTERT

NOBRESSART - ATTERT 68/3-4 Notice explicative CARTE HYDROGÉOLOGIQUE DE WALLONIE Echelle : 1/25 000 Photos couverture © SPW-DGARNE(DGO3) Fontaine de l'ours à Andenne Forage exploité Argilière de Celles à Houyet Puits et sonde de mesure de niveau piézométrique Emergence (source) Essai de traçage au Chantoir de Rostenne à Dinant Galerie de Hesbaye Extrait de la carte hydrogéologique de Nobressart - Attert NOBRESSART - ATTERT 68/3-4 Mohamed BOUEZMARNI, Vincent DEBBAUT Université de Liège - Campus d'Arlon Avenue de Longwy, 185 B-6700 Arlon (Belgique) NOTICE EXPLICATIVE 2011 Première édition : Janvier 2005 Actualisation partielle : Mars 2011 Dépôt légal – D/2011/12.796/2 - ISBN : 978-2-8056-0080-7 SERVICE PUBLIC DE WALLONIE DIRECTION GENERALE OPERATIONNELLE DE L'AGRICULTURE, DES RESSOURCES NATURELLES ET DE L'ENVIRONNEMENT (DGARNE-DGO3) AVENUE PRINCE DE LIEGE, 15 B-5100 NAMUR (JAMBES) - BELGIQUE Table des matières I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 9 II. CADRE GEOGRAPHIQUE, GEOMORPHOLOGIQUE ET HYDROGRAPHIQUE ..........................11 II.1. BASSIN DE LA SEMOIS-CHIERS............................................................................................ 11 II.2. BASSIN DE LA MOSELLE........................................................................................................ 11 II.2.1. Bassin de la Sûre ................................................................................................................. 12 -

Belgium-Luxembourg-7-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges, Ghent & Antwerp & Northwest Belgium Northeast Belgium p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Wallonia p183 Luxembourg p243 #_ Mark Elliott, Catherine Le Nevez, Helena Smith, Regis St Louis, Benedict Walker PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUSSELS . 34 ANTWERP Belgium & Luxembourg . 4 Sights . 38 & NORTHEAST Belgium & Luxembourg Tours . .. 60 BELGIUM . 142 Map . 6 Sleeping . 62 Antwerp (Antwerpen) . 144 Belgium & Luxembourg’s Eating . 65 Top 15 . 8 Around Antwerp . 164 Drinking & Nightlife . 71 Westmalle . 164 Need to Know . 16 Entertainment . 76 Turnhout . 165 First Time Shopping . 78 Lier . 167 Belgium & Luxembourg . .. 18 Information . 80 Mechelen . 168 If You Like . 20 Getting There & Away . 81 Leuven . 174 Getting Around . 81 Month by Month . 22 Hageland . 179 Itineraries . 26 Diest . 179 BRUGES, GHENT Hasselt . 179 Travel with Children . 29 & NORTHWEST Haspengouw . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 BELGIUM . 83 Tienen . 180 Bruges . 85 Zoutleeuw . 180 Damme . 103 ALEKSEI VELIZHANIN / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / VELIZHANIN ALEKSEI Sint-Truiden . 180 Belgian Coast . 103 Tongeren . 181 Knokke-Heist . 103 De Haan . 105 Bredene . 106 WALLONIA . 183 Zeebrugge & Western Wallonia . 186 Lissewege . 106 Tournai . 186 Ostend (Oostende) . 106 Pipaix . 190 Nieuwpoort . 111 Aubechies . 190 Oostduinkerke . 111 Ath . 190 De Panne . 112 Lessines . 191 GALERIES ST-HUBERT, Beer Country . 113 Enghien . 191 BRUSSELS P38 Veurne . 113 Mons . 191 Diksmuide . 114 Binche . 195 MISTERVLAD / HUTTERSTOCK © HUTTERSTOCK / MISTERVLAD Poperinge . 114 Nivelles . 196 Ypres (Ieper) . 116 Waterloo Ypres Salient . 120 Battlefield . 197 Kortrijk . 123 Louvain-la-Neuve . 199 Oudenaarde . 125 Charleroi . 199 Geraardsbergen . 127 Thuin . 201 Ghent . 128 Aulne . 201 BRABO FOUNTAIN, ANTWERP P145 Contents UNDERSTAND Belgium & Luxembourg Today . -

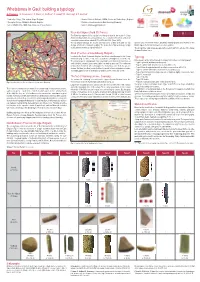

Whetstones in Gaul: Building a Typology A

Whetstones in Gaul: building a typology A. Thiébaux1, E. Goemaere2, X. Deru3, C. Goffioul4, F. Hanut4, D. Henrotay4 & P. Henrich5 1 University of Liège, Phd-student, Liège (Belgium) 4 Service Public de Wallonie, DGO4, Service de l’Archéologie (Belgium) 2 Geological Survey of Belgium, Brussel (Belgium) 5 Deutsche Limeskommission, Bad Homburg (Germany) 3 Lille3, HALMA-IPEL, UMR 8164, Villeneuve d’Ascq (France) Contact : [email protected] Rues-des-Vignes (Nord 59, France) Mer du Nord The Rues-des-Vignes site is a potter’s workshop located in the south of Civitas Nerviorum (Fig. 1) in the present Cambrésis. The occupation of the whole settlement Nereth covers two centuries from about 65-70 to 270-280 A. D. (Deru, 2005). The excavated buildings are houses and spaces for pottery work (pits for clay guest house, a zone with shrines, and finally a burial ground were situated. In the storage, pits for wheel and pottery kilns). The production of this workshop is a high Middle Ages, the Roman ruins were used as quarries. Famars Arras Bavay quality pottery showing a regional diffusion. The fort and the camp village are among the best known fort locations on the Upper Rues-des-Vignes German-Raetian Limes. Revelles Wederath Amiens Arlon (Province of Luxembourg, Belgium) Arlon Trier Dalheim Located in the South of present Belgium, the Arlon’s vicus belongs to the Civitas Typology treverorum (Fig. 1). Since 2006, some excavation’s campaigns are led in the city. 1 Reims Bliesbruck Nine groups can be defined based on primary form without considering wear : Metz They pointed out the organisation of the vicus and revealed areas of settlement, of Beaumont- sur-Oise • Type I: spheroid (multifaceted after used) craft activities (ceramic, glass, metal, fuller’s workshop) and road. -

Décrivez Le Contexte Local Et Présentez Une Synthèse D'une Quinzaine De

Diagnostic de territoire Décrivez le contexte local et présentez une synthèse d’une quinzaine de pages votre diagnostic de territoire. Caractéristiques géographiques Le territoire du projet d’ADL est composé des communes de Léglise, Martelange, Fauvillers et Vaux-sur-Sûre. Les 4 communes disposent de frontières communes. Ce territoire se situe au Centre-Est de la Province de Luxembourg, à cheval sur les arrondissements d’Arlon, Bastogne et Neufchâteau, et est frontalier avec le Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Sur un territoire d’une superficie de 412,57 km² cohabitent Martelange, une des plus petites communes de la Région wallonne (30 km²) et Léglise, une commune particulièrement vaste et étendue (173 km²). Vaux-sur-Sûre et Fauvillers se situent entre ces deux extrêmes, avec respectivement 136 et 74 km². Les communes voisines du territoire sont : V Au sud : Attert, Habay, Tintigny et Chiny; V A l’est : Rombach et Boulaide (Grand-Duché de Luxembourg) ; V Au Nord : Bastogne, Bertogne et Sainte-Ode ; V À l’ouest : Libramont-Chevigny et Neufchâteau Le territoire des 4 communes fait partie de la région agro-géographique de l’Ardenne, marquée par la prédominance de zones agricoles et forestières, et de très faibles superficies bâties. Soulignons l’appartenance des 4 communes au Parc Naturel Haute-Sûre Forêt d’Anlier. Elles constituent 50% du territoire du Parc et en sont, en outre, les plus rurales. L'éloignement du territoire par rapport aux grandes agglomérations urbaines est compensé dans une large mesure par un réseau routier étoffé – E411, E25 et N4 - permettant un accès rapide et aisé. Le territoire se trouve entouré de différents pôles (emplois, services, commerces,…) d’importance variable : Arlon, Libramont-Chevigny, Bastogne et, dans une moindre mesure, Habay et Neufchâteau. -

The Lion, the Rooster, and the Union: National Identity in the Belgian Clandestine Press, 1914-1918

THE LION, THE ROOSTER, AND THE UNION: NATIONAL IDENTITY IN THE BELGIAN CLANDESTINE PRESS, 1914-1918 by MATTHEW R. DUNN Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for departmental honors Approved by: _________________________ Dr. Andrew Denning _________________________ Dr. Nathan Wood _________________________ Dr. Erik Scott _________________________ Date Abstract Significant research has been conducted on the trials and tribulations of Belgium during the First World War. While amateur historians can often summarize the “Rape of Belgium” and cite nationalism as a cause of the war, few people are aware of the substantial contributions of the Belgian people to the war effort and their significance, especially in the historical context of Belgian nationalism. Relatively few works have been written about the underground press in Belgium during the war, and even fewer of those works are scholarly. The Belgian underground press attempted to unite the country's two major national identities, Flemings and Walloons, using the German occupation as the catalyst to do so. Belgian nationalists were able to momentarily unite the Belgian people to resist their German occupiers by publishing pro-Belgian newspapers and articles. They relied on three pillars of identity—Catholic heritage, loyalty to the Belgian Crown, and anti-German sentiment. While this expansion of Belgian identity dissipated to an extent after WWI, the efforts of the clandestine press still serve as an important framework for the development of national identity today. By examining how the clandestine press convinced members of two separate nations, Flanders and Wallonia, to re-imagine their community to the nation of Belgium, historians can analyze the successful expansion of a nation in a war-time context. -

2356. Construction Theme Sale

2356. Construction Theme Sale Sale Information Number of items : 132 Location : Escanaffles (Belgium) Tarcienne (Belgium) baillamont (Belgium) Belgrade (Belgium) Bischheim (France) gilly (Belgium) Hornu (Belgium) Malonne (Belgium) Namur (Belgium) paliseul (Belgium) Riesenhof (Luxembourg) saint-hubert (Belgium) RESTEIGNE (Belgium) Manage (Belgium) ARLON (Belgium) Soignies (Belgium) Ethe (Belgium) Thimeon (Belgium) Marchin (Belgium) carnieres (Belgium) Mont Saint Guibert (Belgium) Mainvault (Belgium) Liège (Belgium) Start date : 10 February 2021 as from 17:00 End date : 24 February 2021 as from 18:30 Viewing day : 29 January 2021 from 16:00 to 17:00 Rue Provinciale , 214 7760 Escanaffles (BE) 01 February 2021 from 17:30 to 19:00 de la barrière, 35/B 5651 Tarcienne (BE) 04 February 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 sedan, 6 5555 baillamont (BE) 04 February 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 Rue Vincent, 25 5001 Belgrade (BE) 04 February 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 Rue de l'atome, 2 67800 Bischheim (FR) 04 February 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 rue de la verrerie , 20 6060 gilly (BE) 04 February 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 rue de Mons, 320 7301 Hornu (BE) 04 February 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 d'insevaux, 157/1 5020 Malonne (BE) 04 February 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 Rue du grand babin , 108 5020 Namur (BE) 04 February 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 ruelle coleau colette, 8/2 6850 paliseul (BE) 04 February 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 Zone industrielle, 10 8821 Riesenhof (LU) 04 February 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 du fays, 8 6870 saint-hubert (BE) 04 February 2021 from 17:30 to 17:45 -

Entreprendre En Province De Luxembourg & Alentours

ENTREPRENDRE en PROVINCE de LUXEMBOURG & alentours ... pour vous accompagner, des pros à votre service, Avec le soutien du Fonds Social Européen, l’Union européenne et les autorités publiques investissent dans votre avenir à tous les niveaux ! Avec le soutien de la Direction de l’Économie de la Province de Luxembourg Plaquette réalisée par la plate-forme Création d’Activité du Luxembourg belge pilotée par le FOREM - Editeur responsable : M.-K Vanbockestal, Boulevard Tirou, 104 - 6000 Charleroi De l’idée au développement de votre activité, des pros vous accompagnent, gratuitement ! Diplôme de gestion ? Accès à la profession ? Etude de marché ? Plan d’affaires ? Plan financier ? Faisabilité ? Viabilité ? Construire un réseau ? Ant IndéPEnd PRojEt d’ tIon du Je veux devenir indépendant PRépara Qui peut m’orienter ? • Etude et validation du projet Ions • Préparation du dossier de financement et du plan d’affaires mAt . InfoR Accompagnement soutenu Conseils personnalisés • Accès à la gestion • Bilan de compétences • Informations sur le statut d’indépendant et sur les aides disponibles • Information et relais vers la structure de création d’entreprise • Recherche et accès aux aides publiques Information, conseil et aide à la création d’asbl et d’entreprises d’économie sociale De l’idée au développement: des étapes indispensables Gérer au quotidien ? Asseoir sa visibilité ? Augmenter son chiffre d’affaires ? Activer son réseau ? Fidéliser la clientèle ? Engager ? S’informer sur les aides ? l’actIvIté Démarrer ? Commercialiser ? Et dévEloPPEmEnt -

Horaire Et Informations Pratiques Lieu Et Accès

Horaire et Informations pratiques Lieu et accès Accueil du public Lieu Province de * Participation gratuite Walexpo Un coup de pouce à l’emploi Rue des Aubépines 50, 6800 Libramont * Le Walexpo est accessible sans interruption de 9h à 17h Une rencontre avec des entreprises qui * Boissons et sandwichs en vente sur place Pour vous aider à vous y rendre : recrutent * Accueil gratuit pour les enfants non scolarisés * www.luxcovoiturage.be en partenariat avec Prémaman Libramont * www.damier.be Luxembourg La «Job-Mobile» de Damier au 063/38 40 22 Informations disponibles au : Tél.: 063/212.636 Itinéraire : [email protected] * En venant d’Arlon ou de Namur : www.province.luxembourg.be Prendre l’autoroute E411 – Sortie 26 Verlaine – rubrique «Economie/Rendez-vous avec l’emploi» Libramont Prendre direction «Libramont» Conférences Ateliers A l’entrée de Recogne, prendre la route à droite direction Halle aux foires – Walexpo (juste avant le Conseils avant Prendre soin de soi t 10h00 - 11h00 magasin Moka d’Or) n entretien d’embauche Au rond-point, prendre la 1ère à droite o am Le contrat de travail Entretien d’embauche ibr 11h30 - 12h30 * En venant de Marche : L interactif Prendre la N4 direction Arlon – Bouillon - Reims Conseils CV et lettre Entretien d’embauche 13h30 - 14h30 Prendre la N89 direction Bouillon - St-Hubert de motivation interactif Prendre la sortie Recogne, tourner à gauche vers 15h00 - 16h00 Les métiers en pénurie Créer son activité Recogne et prendre tout droit dans le rond-point en direction de Neufchâteau Visites d’entreprises -

Belgian Laces

Belgian Laces Rolle Volume 22#86 March 2001 BELGIAN LACES Official Quarterly Bulletin of THE BELGIAN RESEARCHERS Belgian American Heritage Association Our principal objective is: Keep the Belgian Heritage alive in our hearts and in the hearts of our posterity President/Newsletter editor Régine Brindle Vice-President Gail Lindsey Treasurer/Secretary Melanie Brindle Deadline for submission of Articles to Belgian Laces: January 31 - April 30 - July 31 - October 31 Send payments and articles to this office: THE BELGIAN RESEARCHERS Régine Brindle - 495 East 5th Street - Peru IN 46970 Tel/Fax:765-473-5667 e-mail [email protected] *All subscriptions are for the calendar year* *New subscribers receive the four issues of the current year, regardless when paid* ** The content of the articles is the sole responsibility of those who wrote them* TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Editor - Membership p25 Ellis Island American Family Immigration History Center: p25 "The War Volunteer” by Caspar D. p26 ROCK ISLAND, IL - 1900 US CENSUS - Part 4 p27 "A BRIEF STOP AT ROCK ISLAND COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY,"by Michael John Neill p30 Declarations of Intention, Douglas Co. Wisconsin, Part 1, By John BUYTAERT, MI p32 History of Lace p35 DECLARATIONS OF INTENTION — BROWN COUNTY, WISCONSIN, by MaryAnn Defnet p36 In the Land of Quarries: Dongelberg-Opprebais, by Joseph TORDOIR p37 Belgians in the United States 1990 Census p39 Female Labor in the Mines, by Marcel NIHOUL p40 The LETE Family Tree, Submitted by Daniel DUPREZ p42 Belgian Emigrants from the Borinage, Combined work of J. DUCAT, D. JONES, P.SNYDER & R.BRINDLE p43 The emigration of inhabitants from the Land of Arlon, Pt 2, by André GEORGES p45 Area News p47 Queries p47 Belgian Laces Vol 23-86 March 2001 Dear Friends, Just before mailing out the December 2000 issue of Belgian Laces, and as I was trying to figure out an economical way of reminding members to send in their dues for 2001, I started a list for that purpose. -

European Parliament

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2004 2009 Committee on Petitions 20.02.2009 NOTICE TO MEMBERS Subject: Petition 0680/2008 by H. den Broeder (Dutch), on alleged discrimination on grounds of nationality in the granting of price reductions by Audi (Volkswagen Group) 1. Summary of petition The petitioner is a Dutch EU official based in Luxembourg, and is entitled to the special diplomatic sales conditions granted by certain car manufacturers for international civil servants and diplomats. Reading the conditions applied by Audi in Luxembourg and Belgium, he noticed that the Audi dealer in Arlon (Belgium), on the instructions of the Audi importer for Belgium, uses two different reduction percentages: a higher percentage (15%) granted to people with Belgian nationality or having links with Belgium (e.g. living or owning property there), and a lower percentage (9%) applied to everyone else (non-Belgians and those without any links to Belgium). The existence of two different percentages was confirmed in a conversation with the importer’s representative. Two reasons were given: (1) the fact that there is an Audi importer for Luxembourg and one for Belgium, and that if ‘Belgium’ granted the same high percentage reduction for customers from Luxembourg as for Belgians (or persons with a link to Belgium) this would lead to an ‘exodus of customers’ from Luxembourg to Belgium; and (2) that Audi Belgium does not have the financial leeway to grant the high percentage reduction to everyone. The petitioner considers, that being so, that this constitutes discrimination on grounds of nationality. 2. Admissibility Declared admissible on 21 October 2008. The Commission was asked for information (Rule 192(4)). -

About... the History of Luxembourg

Grand Duchy of Luxembourg ABOUT … the History of Luxembourg Despite its small size – 2,586 km2 and home to 590,700 in- CAPITAL: habitants – the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg is a sovereign LUXEMBOURG state with a rich history. Nestled between France, Belgium NEIGHBOURING and Germany in the heart of Europe, it has been involved COUNTRIES: in the great European developments. The turbulent past GERMANY of the Grand Duchy is a true mirror of European history. BELGIUM During the Middle Ages, its princes wore the crown of the FRANCE Holy Roman Empire. In Early Modern Times, its fortress was AREA: a major bone of contention in the battle between the great 2,586 KM2 powers. Before obtaining its independence during the 19th century, Luxembourg lived under successive Burgundian, POPULATION: Spanish, French, Austrian and Dutch sovereignty. During 590,700 INHABITANTS, the 20th century, this wealthy and dynamic country acted INCLUDING 281,500 FOREIGNERS as a catalyst in the unification of Europe. FORM OF GOVERNMENT: CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCHY Grand Duchy of Luxembourg ABOUT … the History of Luxembourg Despite its small size – 2,586 km2 and home to 590,700 in- CAPITAL: habitants – the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg is a sovereign LUXEMBOURG state with a rich history. Nestled between France, Belgium NEIGHBOURING and Germany in the heart of Europe, it has been involved COUNTRIES: in the great European developments. The turbulent past GERMANY of the Grand Duchy is a true mirror of European history. BELGIUM During the Middle Ages, its princes wore the crown of the FRANCE Holy Roman Empire. In Early Modern Times, its fortress was AREA: a major bone of contention in the battle between the great 2,586 KM2 powers. -

Tableau De Bord Socio-Économique De La Province De Luxembourg

Tableau de bord socio-économique de la province de Luxembourg avec le soutien du Collège provincial de la Province de Luxembourg Ce document a été réalisé par l’équipe technique du REAL, qui rassemble: Chers lecteurs, Daniel CONROTTE, Cellule Développement Durable de la Province de Luxembourg Véritable scanner socio-économique de la province de Luxembourg, l’ouvrage que vous Jocelyne COUSET, Promemploi Marie-Caroline DETROZ, Ressources Naturelles Développement asbl tenez entre vos mains est l’outil indispensable pour cerner, chiffres à l’appui, les réalités, Adeline DUSSART, Le Forem enjeux et singularités de notre territoire. Edith GOBLET, Direction de l’Economie de la Province de Luxembourg Catherine HABRAN, Instance Bassin Enseignement qualifiant – Formation – Emploi Dans de trop nombreux domaines, notre province est encore sous-estimée. Des publi- Christophe HAY, Chambre de commerce et d’industrie du Luxembourg belge cations telles que ce tableau de bord socio-économique sont donc nécessaires, je dirais Suzanne KEIGNAERT, Cellule Développement Durable de la Province de Luxembourg Sylvie LEFEBVRE, Promemploi même indispensable, non seulement pour défendre et exporter notre territoire au-delà Sophie MAHIN, Observatoire de la santé de la Province de Luxembourg de ses frontières, mais également pour que les Luxembourgeois eux-mêmes prennent Pierre PEETERS, Direction de l’Economie Rurale de la Province de Luxembourg Alexandre PETIT, IDELUX-AIVE conscience de tout le potentiel socio-économique de notre province. Bertrand PETIT, FTLB Christine VINTENS, NGE asbl La ruralité a trop souvent été perçue comme un frein au développement. Pourtant, à l’heure Le secrétariat a été assuré par Carline BAQUET, Direction de l’Economie de la Province de Luxembourg actuelle, les perspectives économiques de la «verte province» sont nombreuses.