The Search for “Self”: Cultural Identity Through Representations of Parent-Child Relationships in Instructions Not Included (2013) and Under the Same Moon (2007)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Time-Loop Chronicles

Time-Loop Chronicles The Day the Earth Fell Backwards Title: The Time-Loop Chronicles – The Day the Earth Fell Backwards Paperback: 318 pages Language: English ISBN-10: 978-1548297091 ISBN-13: 10:1548297097 1st edition Large Print April 2017 Product Dimensions: 8.5 x 11 inches Publisher: Create Space Author: John V. Panella Page | 1 Time-Loop Chronicles About Author John V. Panella has been writing off and on for decades. Back in the early 70’s he dabbled in writing scripts for television shows and movies for personal enjoyment. It was then in the 80’s he began to get serious and started writing about potential errors in our historical archives and records. This led him into a series of writings and his first book dealing with codes, prophecies, history, religion and spiritual belief paradigms. For the last 25-years, he has spent a lot of his time sharing his discoveries, writing hundreds of articles, magazines, along with many books. Then one day he decided why not go back to his past and leave the non- fiction genre behind for a while and get back to his first love, Science Fiction and Time Travel. Instead of trying to fit all the pieces of our past, why not change a few of them with scenarios that make you wonder, what if this happened, or that happened, and what if what we have been told is simply not true? After spending so much dedicated time trying to make sure everything he had written was accurate, he decided, why not throw it all up in the air, and let the chips fall where they may. -

Draw Us Something: Ekphrasis in Reverse, a Meeting of Minds

Dominican Scholar Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Liberal Arts and Education | Graduate Theses Student Scholarship December 2019 Draw Us Something: Ekphrasis In Reverse, A Meeting of Minds Cara Makuh Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HUM.07 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Makuh, Cara, "Draw Us Something: Ekphrasis In Reverse, A Meeting of Minds" (2019). Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Theses. 7. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HUM.07 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberal Arts and Education | Graduate Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This thesis, written under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor and approved by the department chair, has been presented to and accepted by the Master of Arts in Humanities Program in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts in Humanities. An electronic copy of of the original signature page is kept on file with the Archbishop Alemany Library. Cara Makuh Candidate Judy Halebsky, PhD Program Chair Thomas Burke, MFA First Reader Robert Bradford, MA Second Reader This master's thesis is available at Dominican Scholar: https://scholar.dominican.edu/humanities- masters-theses/7 Draw Us Something: Ekphrasis In Reverse, A Meeting of Minds By Cara Makuh A culminating thesis submitted to the faculty of Dominican University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Humanities Dominican University of California San Rafael, CA December 2019 ii Copyright © Cara Makuh 2019. -

N° Artiste Titre Formatdate Modiftaille 14152 Paul Revere & the Raiders Hungry Kar 2001 42 277 14153 Paul Severs Ik Ben

N° Artiste Titre FormatDate modifTaille 14152 Paul Revere & The Raiders Hungry kar 2001 42 277 14153 Paul Severs Ik Ben Verliefd Op Jou kar 2004 48 860 14154 Paul Simon A Hazy Shade Of Winter kar 1995 18 008 14155 Me And Julio Down By The Schoolyard kar 2001 41 290 14156 You Can Call Me Al kar 1997 83 142 14157 You Can Call Me Al mid 2011 24 148 14158 Paul Stookey I Dig Rock And Roll Music kar 2001 33 078 14159 The Wedding Song kar 2001 24 169 14160 Paul Weller Remember How We Started kar 2000 33 912 14161 Paul Young Come Back And Stay kar 2001 51 343 14162 Every Time You Go Away mid 2011 48 081 14163 Everytime You Go Away (2) kar 1998 50 169 14164 Everytime You Go Away kar 1996 41 586 14165 Hope In A Hopeless World kar 1998 60 548 14166 Love Is In The Air kar 1996 49 410 14167 What Becomes Of The Broken Hearted kar 2001 37 672 14168 Wherever I Lay My Hat (That's My Home) kar 1999 40 481 14169 Paula Abdul Blowing Kisses In The Wind kar 2011 46 676 14170 Blowing Kisses In The Wind mid 2011 42 329 14171 Forever Your Girl mid 2011 30 756 14172 Opposites Attract mid 2011 64 682 14173 Rush Rush mid 2011 26 932 14174 Straight Up kar 1994 21 499 14175 Straight Up mid 2011 17 641 14176 Vibeology mid 2011 86 966 14177 Paula Cole Where Have All The Cowboys Gone kar 1998 50 961 14178 Pavarotti Carreras Domingo You'll Never Walk Alone kar 2000 18 439 14179 PD3 Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is kar 1998 45 496 14180 Peaches Presidents Of The USA kar 2001 33 268 14181 Pearl Jam Alive mid 2007 71 994 14182 Animal mid 2007 17 607 14183 Better -

![[B]Original Studio Albums[/B] 1981 - Face Value (Atlantic, 299 143) 01](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1319/b-original-studio-albums-b-1981-face-value-atlantic-299-143-01-2591319.webp)

[B]Original Studio Albums[/B] 1981 - Face Value (Atlantic, 299 143) 01

[b]Original Studio Albums[/b] 1981 - Face Value (Atlantic, 299 143) 01. In The Air Tonight 02. This Must Be Love 03. Behind The Lines 04. The Roof Is Leaking 05. Droned 06. Hand In Hand 07. I Missed Again 08. You Know What I Mean 09. Thunder And Lightning 10. I'm Not Moving 11. If Leaving Me Is Easy 12. Tomorrow Never Knows 1982 - Hello, I Must Be Going! (WEA, 299 263) 01. I Don't Care Anymore 02. I Cannot Believe It's True 03. Like China 04. Do You Know, Do You Care 05. You Can't Hurry Love 06. It Don't Matter To Me 07. Thru These Walls 08. Don't Let Him Steal Your Heart Away 09. The West Side 10. Why Can't It Wait 'til Morning 1985 - No Jacket Required (WEA, 251 699-2) 01. Sussudio 02. Only You Know & I Know 03. Long Long Way To Go 04. I Don't Wanna Know 05. One More Night 06. Don't Lose My Number 07. Who Said I Would 08. Doesn't Anybody Stay Together Anymore 09. Inside Out 10. Take Me Home 11. We Said Hello Goodbye 1989 - But Seriously (WEA, 2292-56984-2) 01. Hang In Long Enough 02. That's Just The Way It Is 03. Do You Remember 04. Something Happened On The Way To Heaven 05. Colours 06. I Wish It Would Rain Down 07. Another Day In Paradise 08. Heat On The Street 09. All Of My Life 10. Saturday Night And Sunday Morning 11. -

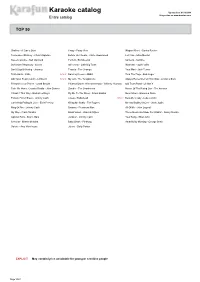

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 01/10/2019 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 01/10/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Crazy - Patsy Cline Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Let It Go - Idina Menzel Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Perfect - Ed Sheeran Santeria - Sublime Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Girl Crush - Little Big Town Wannabe - Spice Girls Don't Stop Believing - Journey Tequila - The Champs Your Man - Josh Turner Truth Hurts - Lizzo EXPLICIT Dancing Queen - ABBA Turn The Page - Bob Seger Old Town Road (remix) - Lil Nas X EXPLICIT My Girl - The Temptations Always Remember Us This Way - A Star is Born Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Old Town Road - Lil Nas X Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Zombie - The Cranberries House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Creep - Radiohead EXPLICIT Beautiful Crazy - Luke Combs Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Dreams - Fleetwood Mac All Of Me - John Legend My Way - Frank Sinatra Black Velvet - Alannah Myles These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Jackson - Johnny Cash Your Song - Elton John Señorita - Shawn Mendes Baby Shark - Pinkfong Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Valerie - Amy Winehouse Jolene - Dolly Parton EXPLICIT -

February 26 March 4

FEBRUARY 26 ISSUE MARCH 4 Orders Due January 29 5 Orders Due February 5 axis.wmg.com 2/23/16 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Hawkwind Space Ritual (2LP 180 Gram Vinyl) PRH A 825646120758 407156 34.98 1/22/16 Jethro Tull Living In The Past (2LP 180 Gram Vinyl) PRH A 825646041930 551965 34.98 1/22/16 Morrissey Bona Drag (2LP) RRW A 825646775545 542347 34.98 1/22/16 Red Hot Chili Peppers I'm With You (2LP) WB A 093624924340 551828 29.98 1/22/16 Red Hot Chili Peppers Stadium Arcadium (4LP) WB A 093624439110 44391 39.98 1/22/16 Last Update: 01/05/16 For the latest up to date info on this release visit axis.wmg.com. ARTIST: Hawkwind TITLE: Space Ritual (2LP 180 Gram Vinyl) Label: PRH/Rhino/Parlophone Config & Selection #: A 407156 Street Date: 02/23/16 Order Due Date: 01/22/16 UPC: 825646120758 Box Count: 20 Unit Per Set: 2 SRP: $34.98 Alphabetize Under: H TRACKS Full Length Vinyl 1 Side A Side B 01 Earth Calling 01 Lord Of Light 02 Born To Go 02 Black Corridor 03 Down Through The 03 Space Is Deep Night 04 Electronic No 1 04 The Awakening Full Length Vinyl 2 Side A Side B 01 Orgone Accumulator 01 Seven By Seven 02 Upside Down 02 Sonic Attack 03 10 Seconds Of Forever 03 Time We Left This World 04 Brainstorm Today 04 Master Of The Universe 05 Welcome To The Future ALBUM FACTS Genre: Rock Description: Recorded live in December 1972 and released the following year, Space Ritual is an excellent document of Hawkwind's classic lineup, underscoring the group's status as space rock pioneers. -

Chart-Chronology PHIL COLLINS

www.chart-history.net vdw56 PDF-file with all chart-entries plus covers on https://chart-history.net/cc/cc-phil-collins.pdf PHIL COLLINS Chart-Chronology Singles and Albums Germany United Kingdom From the 1950ies U S A to the current charts compiled by Volker Dörken Chart - Chronology The Top-100 Singles and Albums from Germany, the United Kingdom and the USA Phil Collins Philip David Charles Collins LVO (born 30 January 1951) is an English drummer, singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, record producer, and actor. He was the drummer and singer of the rock band Genesis, and is also a solo artist. Singles 49 32 19 10 34 Longplay 23 20 15 8 81 B P Top 100 Top 40 Top 10 # 1 B P Top 100 Top 40 Top 10 # 1 1 11 37 21 11 2 1 45 22 18 14 5 1 8 36 27 13 3 1 26 16 14 12 6 1 15 27 21 14 7 1 10 14 11 6 2 Singles D G B U S A 1 In The Air Tonight 03/1981 1 1 01/1981 2 05/1981 19 2 I Missed Again 05/1981 23 03/1981 14 03/1981 19 3 If Leaving Me Is Easy 08/1981 61 05/1981 17 4 Thru' These Walls 10/1982 56 5 You Can't Hurry Love 01/1983 3 12/1982 1 2 11/1982 10 6 I Don't Care Anymore 02/1983 39 7 Don't Let Him Steal Your Heart Away 03/1983 45 8 I Cannot Believe It's True 05/1983 79 9 Why Can't It Wait 'Till Morning 05/1983 89 10 Against All Odds 05/1984 9 04/1984 2 02/1984 1 3 11 Easy Lover ►Philip Bailey & Phil Colins◄ 01/1985 5 03/1985 1 4 11/1984 2 12 Sussudio 02/1985 17 01/1985 12 05/1985 1 1 13 One More Night 04/1985 10 04/1985 4 02/1985 1 2 14 Don't Lose My Number 07/1985 4 15 Take Me Home 07/1985 19 03/1986 7 16 Separate Lives (Theme From "White -

Platforms, Promotion, and Product Discovery: Evidence from Spotify Playlists

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Aguiar, Luis; Waldfogel, Joel Working Paper Platforms, Promotion, and Product Discovery: Evidence from Spotify Playlists JRC Digital Economy Working Paper, No. 2018-04 Provided in Cooperation with: Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Commission Suggested Citation: Aguiar, Luis; Waldfogel, Joel (2018) : Platforms, Promotion, and Product Discovery: Evidence from Spotify Playlists, JRC Digital Economy Working Paper, No. 2018-04, European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), Seville This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/202233 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu JRC Digital Economy Working Paper 2018-04 Platforms, Promotion, and Product Discovery: Evidence from Spotify Playlists Luis Aguiar Joel Waldfogel (University of Minnesota and NBER) May 2018 This publication is a Working Paper by the Joint Research Centre, the European Commission’s in- house science service. -

Film Diplomacy Under the Bush and Obama Administration

Film Diplomacy Under the Bush and Obama Administration: A Film Analysis of the American Film Institute’s Project: 20/20 and the Sundance Institute’s Film Forward Program THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chen Wang Graduate Program in Arts Policy and Administration The Ohio State University 2015 Master’s Examination Committee: Professor Margaret J. Wyszomirski, Advisor Professor Wayne P. Lawson Copyright by Chen Wang 2015 Abstract The American Film Institute’s Project: 20/20 was a program sponsored by the State Department in which American and international filmmakers traveled with their films to domestic and international locations. The program, launched in 2006, ceased its partnership with the American Film Institute after its fourth year in 2009-2010 and was replaced by a new program, Film Forward: Advancing Cultural Dialogue. This paper examines the similarities and differences between the two programs by analyzing the themes and content of the selected films, in order to investigate how the selection of films may have been influenced by the political and ideological orientation of the presidential administrations, US foreign policy, and diplomatic objectives. The paper contributes to the ongoing scholarly discussion surrounding the use of film as a tool of public diplomacy. !ii To my parents, !iii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without my two committee members Dr. Margaret Wyszomirski and Dr. Wayne Lawson who have showed such great interest in my research and provided invaluable advice as I complete this project. -

Phil Collins

Chart - History Singles All chart-entries in the Top 100 Peak:1 Peak:1 Peak: 1 Germany / United Kindom / U S A Phil Collins No. of Titles Positions Philip David Charles Collins LVO (born 30 Peak Tot. T10 #1 Tot. T10 #1 January 1951) is an English drummer, singer, 1 37 11 2 499 94 11 songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, record 1 36 13 3 286 64 8 producer, and actor. He was the drummer and 1 27 14 7 470 85 15 singer of the rock band Genesis, and is also a solo artist. 1 49 19 10 1.255 243 34 ber_covers_singles Germany U K U S A Singles compiled by Volker Doerken Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 1 In The Air Tonight 03/1981 1 1 32 1401/1981 2 32 5 05/1981 19 17 2 I Missed Again 05/1981 23 16 03/1981 14 8 03/1981 19 16 3 If Leaving Me Is Easy 08/1981 61 5 05/1981 17 8 4 Thru' These Walls 10/1982 56 2 5 You Can't Hurry Love 01/1983 3 21 1112/1982 1 2 16 811/1982 10 21 3 6 I Don't Care Anymore 02/1983 39 11 7 Don't Let Him Steal Your Heart Away 03/1983 45 5 8 I Cannot Believe It's True 05/1983 79 4 9 Why Can't It Wait 'Till Morning 05/1983 89 3 10 Against All Odds 05/1984 9 16 381004/1984 2 18 02/1984 1 3 24 11 Easy Lover 01/1985 5 17 5603/1985 1 4 13 11/1984 2 23 7 ► Philip Bailey & Phil Colins 12 Sussudio 02/1985 17 13 01/1985 12 9 05/1985 1 1 17 6 13 One More Night 04/1985 10 13 2404/1985 4 10 02/1985 1 2 18 6 14 Don't Lose My Number 07/1985 4 18 4 15 Take Me Home 07/1985 19 9 03/1986 7 16 5 16 Separate Lives (Theme From "White Nights") 02/1986 50 6 11/1985 4 15 6910/1985 1 1 21 ► Phil Collins & Marilyn Martin 17 In The -

Prisoner Express Is Designed to Bring You Opportunities for Creative Self

PRISONER EXPRESS NEWSLETTER FALL 2011 Prisoner Express is designed to provide you with only 3 reasons. If you want to be reinstated please let me opportunities for creative self-expression, educational know. materials as well as a vehicle to bring your ideas, Reason 1- We have not heard from you in 8 writings and artwork out from behind the walls and into months. As I get ready to send this newsletter I check to ―free society‖. We can do this in a variety of ways, and I see when I last got mail from any of you. If you have rely on you who are reading this to help continue to written something since Feb 11 to us you stay current, create and reinvent this program so that it continues to and will receive our mailing. It is up to you to write serve you while also highlighting the humanity of every so often. Returning the registration form or a short incarcerated men and women. note telling us what programs you want to participate in, is enough to keep you registered to receive the For those of you new to the program I‘d like to newsletter. introduce myself and then return back to the theme of Reason 2- If the previous letter we send you this program, its‘ purpose and your role in creating it. bounces back to us we remove you from the current list. My name is Gary and for the past 10 years I have been If you see someone down the way getting mail from us co-creating Prisoner Express with those of you who are that you think should also come to you send us a note writing to me and participating in this project. -

July 1-30, 2010

An Appalachian SummerJuly 1-30, Festival2010 APPALACHIAN STATE UNIVERSITY | BOONE, NORTH CAROLINA Janis Ian & Karla Bonoff JULY 1 Summer Exhibition Celebration JULY 2 Distinguished Faculty Concert JULY 3 “Me & Orson Welles“ Film, JULY 5 The Broyhill Chamber Ensemble JULY 7, 14, 25 Amy Sedaris JULY 9 The Golden Dragon Acrobats JULY 10 Eastern Festival Orchestra with Barry Douglas JULY 11 “Vanya on 42nd Street“ Film, JULY 12 Lar Lubovitch Dance Company JULY 16 Patti LuPone JULY 17 Eastern Festival Orchestra with Tianwa Yang JULY 18 “Every Little Step“ Film, JULY 19 John Pizzarelli JULY 22 Wild & Scenic Film Festival JULY 23 Rosen Sculpture Walk & Competition JULY 24 Blood, Sweat & Tears JULY 24 “Under the Same Moon“ Film, JULY 26 Jazz Beneath the Stars at Westglow JULY 29 Ralph Stanley & Cherryholmes JULY 30 ON AND AROUND THE CAMPUS OF APPALACHIAN STATE UNIVERSITY, BOONE, NC JULY 2010 CALENDAR OF EVENTS FIND US ON: An Appalachian Summer Festival SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Triad Stage Janis Ian Summer Distinguised Bus Trip: & Exhibition Faculty “Providence Karla Celebration Concert Gap” Bonoff: at the 8PM, RCH PAGE 42 PAGE 93 Songs of a Turchin Basic Batik 27 Generation1 2 3 Workshop 8PM, FA PAGE 77 Center 7PM, TCVA PAGE 100 PAGE 103 Dinner, Show Film Broyhill Belk Lecturer Amy Golden Dragon & Fireworks “Me and Orson Anne Acrobats Chamber Sedaris 8PM, FA PAGE 67 Welles” 8PM, FA PAGE 95 at Westglow 8PM, FA PAGE 110 Ensemble Whisnant Resort & Spa 8PM, RCH PAGE 49 3:30PM, BLIC PAGE 102 TCVA Family Day PAGE 102