FLORIDA FIELD NATURALIST Florida Scrub Jay Steals Blue Jay Eggs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migrational Movements of Blue Jays West of the 100Th Meridian

Migrational movementsof Blue Jays west of the 100th meridian Kimberly G. Smith Introduction Since the start of the bird-bandingprogram in movements-- in fall of 1939when 7350Blue Jays North America, the movements of Blue Jays passedHawk Mountain,Pennsylvania, in 16 days (Cyanocittacristata) have been of great interest. in late September(Broun 1941), and in fall of 1962 The first report of bird-bandingrecoveries by the when Blue Jaysinvaded Massachusetts (Nunneley BiologicalSurvey (Lincoln1924) listed 38 Blue Jay 1964). returns, all from the same stationat which they While investigatingthe range extensionof Blue were banded.The secondBiological Survey report Jaysinto westernNorth America(Smith 1978), ! (Lincoln 1927) listed 11 Blue Jays recovered at found that the breedingrange was slowlymoving placesremoved from the originalbanding station, westward,whereas the numberof winter sightings although219 of the 230reports still were returnsat in the PacificNorthwest was increasingdramati- the original station.Seven of these 11 recoveries cally.! was puzzledby the lack of winter sightings were within the samestate as the originalbanding in the Intermountainregion, and decided to ana- station,with the 4 othersall showingsouthward lyze the bandingrecoveries west of the 100thmer- movementsduring fall. Two of these recoveries constituted movements of over 667 kin. Over the idian to determine what pattern might emerge. Here, I presentthat analysis,which stronglysug- next 15 years,many long-distancemovements by geststhat most Blue Jay sightingsin the Pacific bandedBlue Jayswere reported(e.g., Whittle 1928, Northwestare individualsoriginating in western Anon. 1929, Roberts 1936, Stoner 1936), as were Canada rather than birds crossingthe Rockies sightingsof large massmovements or migrationsof from central United States. Blue Jays(e.g., Sherman 1931, Tyrrell 1934,Cottam 1937,Broun 1941,Lewis 1942). -

Blue Jay, Vol.50, Issue 1

FALL FOOD OF THE EASTERN SCREECH-OWL IN MANITOBA KURT M. MAZUR, 15 Attache Place, Winnipeg, Manitoba. R2V 3L3 The Eastern Screech-owl is one of site. Through examination of the prey the most widespread owls in North remains, an owl’s diet can be ac¬ America.4 It ranges from the Gulf of curately quantified.6,8 Mexico north to southern Manitoba, and from Montana to the east coast Starting 13 October 1990, 40 nest of the United States.14 This small boxes were checked for prey (20-24 cm) highly nocturnal owl has remains. Five of these contained pel¬ a diet that is quite varied over its lets and/or bones and feathers, range and throughout the presumably the prey of the resident season.1,4,5,11'12,15,16,18 Several screech-owl. These five boxes, and studies of the Eastern Screech-owl’s the surrounding areas, were checked diet have been published, but none once a week from 13 October to 4 from the northern edge of its November 1990. range.5,15,16,18 Reports of Eastern Screech-owls in Manitoba occur as Prey were identified to species far north as Riding Mountain National when possible. Mean individual prey Park.1 weight was estimated by taking the average weight of five individuals of This study was done near Win¬ each species from the same time of nipeg in autumn, a time when num¬ year, based on data from Manitoba bers and types of prey available are specimen collections.9 From these changing.7,13,16 The study area was individual prey weights a percent in La Barriere Park along the La total weight was calculated for the Salle River, just south of Winnipeg. -

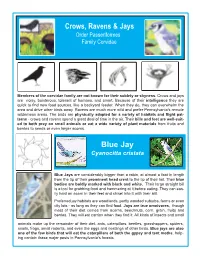

Crows, Ravens, and Jays

Crows, Ravens & Jays Order Passeriformes Family Corvidae Members of the corvidae family are not known for their sublety or shyness. Crows and jays are noisy, boisterous, tolerant of humans, and smart. Because of their intelligence they are quick to find new food sources, like a backyard feeder. When they do, they can overwhelm the area and drive other birds away. Ravens are much more wild and prefer Pennsylvania’s remote wilderness areas. The birds are physically adapted for a variety of habitats and flight pat- terns - crows and ravens spend a great deal of time in the air. Their bills and feet are well-suit- ed to both prey on small animals or eat a wide variety of plant materials from fruits and berries to seeds or even larger acorns. Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata Blue Jays are considerably bigger than a robin, at almost a foot in length from the tip of their prominent head crest to the tip of their tail. Their blue bodies are boldly marked with black and white. Their large straight bill is a tool for grabbing food and hammering at it before eating. They can eas- ily hold an acorn in their feet and chisel into it with their bill. Preferred jay habitats are woodlands, partly wooded suburbs, farms or even city lots - as long as they can find food. Jays are true omnivores, though most of their diet comes from acorns, beechnuts, corn, grain, fruits and berries. They will eat carrion when they find it. All kinds of insects and small animals make up the remainder of their diet: ants, caterpillars, beetles, grasshoppers, spiders, snails, frogs, small rodents, and even the eggs and nestlings of other birds. -

Alaja & Mikkola-33-37

Albinism in the Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa) and Other Owls Pentti Alaja and Heimo Mikkola1 Abstract.—An incomplete albino Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa) was observed in Vesanto and Kajaani, Finland, 1994-1995. The literature pertaining to albinism in owls indicates that total and incomplete albinism has only been reported in 13 different owl species, the Great Gray Owl being the only species with more than five records. Thus six to seven incomplete albino Great Grays have been recorded since 1980 in Canada, Finland, and the United States. ___________________ It would seem that most animals produce Partial albinism may result from injury, physio- occasional albinos; some species do so quite logical disorder, diet, or circulatory problems. frequently whilst this phenomenon is much This type of albinism is most frequently rarer in others. Although albinism in most observed. It is important to note that white avian families is frequently recorded, we know plumage is not necessarily proof of albinism. of very few abnormally white owls. Thus the motive of this paper is to assemble as complete Adult Snowy Owls (Nyctea scandiaca) are a record as possible of white or light color primarily white, but have their feather color mutations of owls which exist or have been derived from a schemochrome feather structure recorded. which possesses little or no pigment. Light reflects within the feather structure and GENETICS OF ALBINISM produces the white coloration (Holt et al. 1995). Albinism is derived from a recessive gene which ALBINISM IN THE GREAT GRAY OWLS inhibits the enzyme tyrosinase. Tyrosine, an amino acid, synthesizes the melanin that is the An extremely light and large Great Gray Owl basis of many avian colors (Holt et al. -

Two Eastern Screech-Owls, Young Naturalists Teachers Guide

MINNESOTA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER Young Naturalists Teachers Guide Prepared by Jack “Two Eastern Screech-Owls” Multidisciplinary Judkins, curriculum Classroom Activities consultant, Bemidji, Teachers guide for the Young Naturalists article “Two Eastern Screech-Owls” by Laura Erickson Minnesota with illustrations by Betsy Bowen. Published in the November-December 2011 Minnesota Conservation Volunteer, or visit www.mndnr.gov/young_naturalists/screech_owls. Young Naturalists teachers guides are provided free of charge to classroom teachers, parents, and students. This guide contains a brief summary of the article, suggested independent reading levels, word count, materials list, estimates of preparation and instructional time, academic standards applications, preview strategies and study questions overview, adaptations for special needs students, assessment options, extension activities, Web resources (including related Conservation Volunteer articles), copy-ready study questions with answer key, and a copy-ready vocabulary sheet and vocabulary study cards. There is also a practice quiz (with answer key) in Minnesota Comprehensive Assessments format. Materials may be reproduced and/or modified a to suit user needs. Users are encouraged to provide feedback through an online survey at www.mndnr.gov/education/ teachers/activities/ynstudyguides/survey.html. If you are downloading articles from the website, please note that only Young Naturalists articles are available in PDF. Summary In this story the reader gets an early-spring glimpse of a -

Evidence for Vocal Learning by a Scrub Jay

202 ShortCommunications [Auk, Vol. 107 OHNO, S. 1967. Sex chromosomes and sex-linked ß J. S. QUINNß F. COOKE, & B. N. WHITE. 1987. genes. New York, Springer. DNA marker analysisdetects multiple maternity PAGE, D. C., M. E. HARPER, J. LOVE, & D. BOTSTEIN. and paternity in singlebroods of the LesserSnow 1984. Occurrence of a transpositionfrom the Goose. Nature 326: 392-394. X-chromosomelong arm to the Y-chromosome SOKAL,R. R., & F. J. ROHLF. 1969. Biometry. San short arm during human evolution. Nature 311: Franciscoß W. H. Freeman and Co. 119-123. SOUTHERN,E.g. 1975. Detection of specific se- ß B. DE MARTINvILLEßD. BARKER,A. WYMAN, R. quencesamong DNA fragmentsseparated by gel WHITEßU. FRANCKE,&D. BOTSTEIN.1982. Single- electrophoresis.J. Mol. Biol. 98: 503-517. copy sequencehybridizes to polymorphic and STRANGEL,P.W. 1986. Lackof effectsfrom sampling homologousloci on human X and Y chromo- blood from small birds. Condor 88: 244-245. somes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79: 5352-5356. TABER,R. D. 1971. Criteria of sexand age. Pp. 325- PRus,S. E., & S.C. SCHMUTZ.1987. Comparative 401 in Wildlife managementtechniquesß 3rd ed. efficiencyand accuracyof surgical and cytoge- (R. H. Giles,Ed.). Washingtonß D.C., The Wildlife netic sexing in Psittacines.Avian Diseases31: Society. 420-424. TONEßM., Y. SAKAKI, T. HASHIGUCHI, & S. MIZUNO. QUINN, T. W., & B. N. WHITE. 1987. Identification of 1984. Genus specificityand extensive methyl- restriction-fragment-lengthpolymorphisms in ation of the W chromosome-specificrepetitive genomicDNA of the LesserSnow Goose(Anser DNA sequencesfrom the domestic fowl, Gallus caerulescenscaerulescens). Mol. Biol. Evol. 4: 126- gallusdomesticus. Chromosoma 89: 228-237. -

Blue Jay Cyanocitta Cristata Adult ILLINOIS RANGE

blue jay Cyanocitta cristata Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The blue jay averages 11 to12 inches in length. It is a Class: Aves large bird with blue feathers and a crest. White Order: Passeriformes feather patches are present in the wings and tail. A black line behind the head extends from each side Family: Corvidae to form a black “necklace” on the throat. This bird ILLINOIS STATUS has white or gray feathers underneath. common, native BEHAVIORS The blue jay is a common, permanent resident statewide in Illinois. However, blue jays do migrate within Illinois, moving to southern Illinois from the northern sections of the state in the winter. The nesting season lasts from April through mid-July. The nest is built in a forest, residential area, orchard or other location where trees are present, from five to 50 feet above the ground. Both sexes construct the nest of twigs, bark, leaves, mosses and string and line it with rootlets. Four or five olive, tan or blue- green eggs with dark markings are laid. Both the male and female take turns incubating the eggs over a 17- to 18-day period. One brood is raised per year. This aggressive bird uses its loud calls (“jay,” “jeeah,” adult “queedle, queedle”) to alert others to possible danger. The blue jay can mimic some other birds, too. It may go to roost in mid-afternoon in the winter months. Found in woodlands and residential ILLINOIS RANGE areas, the blue jay eats nuts, particularly acorns, corn, fruits, insects and dead animals. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

Page 14-17 Winter Survival

Winter Survival Tufted Titmouse (Parus bicolor) Downy Woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) Changing Seasons and Winter Survival: Year-Round Residents shelter in the right environment orAll habitat birds need for health food, water and safety. and general area year-round. They breed andResident raise birdstheir remainyoung in in the the same same area that they spend the winter. Resident birds change behavior to adapt to winter conditions. Carolina Chickadee (Parus carolinensis) Small woodland birds, like locatechickadees, food. titmice These birdsand downy are often woodpeckers, join mixed flocks to seen together at backyard feeders. 14 ChangesWinter Survival in Bird Populations Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) feathers in a fall molt to insulate Many birds grow extra down against winter’s cold. While molting a bird loses worn feathers and grows new ones. Small down feathers grown next to the skin add a thick canlayer add of warmth.more insulation By fluffing and these may feathers to create air pockets, birds Thelook resident twice their Northern normal size! Mockingbird but mimics other bird songs. has no song of its own becomeIn 1933, Tennessee’s72,000 school state children bird voted to decide which bird would greatest number of votes. symbol. The mockingbird won the Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) 15 Winter Survival The American Robin (Turdus migratorius) is a year-round resident in Tennessee. It feeds on insects and worms when these are available. During the fall, large flocks of northern robins migrate or travel to Tennessee to find food. They can be seen eating in fruit bearing trees and shrubs, like dogwood and holly. Robins migrate in large mixed flocks and are noisy when they arrive. -

Pellet-Casting by a Western Scrub-Jay Mary J

NOTES PELLET-CASTING BY A WESTERN SCRUB-JAY MARY J. ELPERS, Starr Ranch Bird Observatory, 100 Bell Canyon Rd., Trabuco Canyon, California 92679 (current address: 3920 Kentwood Ct., Reno, Nevada 89503); [email protected] JEFF B. KNIGHT, State of Nevada Department of Agriculture, Insect Survey and Identification, 350 Capitol Hill Ave., Reno, Nevada 89502 Pellet casting in birds of prey, particularly owls, is widely known. It is less well known that a wide array of avian species casts pellets, especially when their diets contain large amounts of arthropod exoskeletons or vertebrate bones. Currently pellet casting has been documented for some 330 species in more than 60 families (Tucker 1944, Glue 1985). Among the passerines reported to cast pellets are eight species of corvids: the Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) (Lamore 1958, Tarvin and Woolfenden 1999), Pinyon Jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus) (Balda 2002), Gray Jay (Perisoreus canadensis) (Strickland and Ouellet 1993), Black-billed Magpie (Pica hudsonia) (Trost 1999), Yellow-billed Magpie (Pica nuttalli) (Reynolds 1995), American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) (Verbeek and Caffrey 2002), Northwestern Crow (Corvus caurinus) (Butler 1974), and Common Raven (Corvus corax) (Temple 1974, Harlow et al. 1975, Stiehl and Trautwein 1991, Boarman and Heinrich 1999). However, the behavior has not been recorded in the four species of Aphelocoma jays (Curry et al. 2002, Woolfenden and Fitzpatrick 1996, Curry and Delaney 2002, Brown 1994). Here we report an observation of regurgitation of a pellet by a Western Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma californica) and describe the specimen and its contents. The Western Scrub-Jay is omnivorous and forages on a variety of arthropods as well as plant seeds and small vertebrates (Curry et al. -

Blue Jay (Cyanocitta Cristata) Gail Mcpeek

Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) Gail McPeek Point Pelee National Park, Ontario (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) 10/7/2007 © Jerry Jourdan The Blue Jay is a notoriously noisy bird, except Lake Michigan and Lake Huron shorelines, and at Whitefish Point Bird Observatory in the UP. at nesting time when adults are quiet and In 2007, spring counts at WPBO recorded more stealthy, being careful not to draw attention to than 9,000 Blue Jays from 9 to 31 May, with their reproductive goal and, what will soon high counts of 1,500 and 1,170 on 18 May and become more noisy Blue Jays. This bird is very 23 May, respectively (WPBO 2007). Fall easy to identify, having bold blue plumage with migration occurs from mid-September to late various white and black markings, a regal crest, October. and a long tail. It is a member of the Corvid family, and one of two jays found in Michigan. Distribution Blue Jays breed throughout the Michigan The Blue Jay is a common permanent resident landscape. Their loud “jaaaay” calls resound across the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. and wherever there is some forest or forest edge, and southern Canada. For several decades, a that includes the multitude of wood-lands westward expansion has been underway with provided by our parks, golf courses, and occasional nesting as far west as Oregon and neighborhoods. Such a ubiquitous distribution British Columbia. Although recognized as a is due, in large part, to an omnivorous diet. permanent resident throughout its range, Foods include corn, grains, and fruits, sunflower numbers do withdraw in winter from northern seeds and suet, insects, and most importantly, areas. -

Blue Jay Cyanocitta Cristata

Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata The Blue Jay is an abundant, eastern Nearc tic species that is expanding westward. It now occurs regularly as far west as Colo rado, where it has been found to hybridize with the Steller's Jay. It is one of the most common, conspicuous, and well-known birds in the Northeast and has certainly benefited from the post-World War II bird feeder explosion. Although inhabiting both deciduous and coniferous woods, it is quite tolerant of humans and will nest in towns and suburbs. It is still, however, essentially a woodland bird, and is most abundant in oak and beech forests. Although an opportunistic omnivore, the grass and other soft material in the center Blue Jay's diet is three-quarters vegetarian: to form a deep cup. The eggs (4 to 7 per acorns, beech nuts, and corn are its staple clutch) are buff or greenish spotted with food. In the summer its diet becomes mostly brown (more heavily at the large end). Of insectivorous, and at all times of the year it 18 clutches, none had more than 5 eggs. is a sharp-eyed scavenger. The Blue Jay's Although Blue Jays are noted for their vocal habit of taking food and storing it in a crev alarm calls, during the breeding season they ice or other hiding place makes it an un become furtive and quiet. When predators welcome visitor at some feeding stations. appear the territorial tea cup call is given, The Blue Jay breeds in all regions of Ver and predators are assailed; but around the mont. -

Jim Baker's Blue-Jay Yarn

001-149_Twain_VII_LOA_791109_001-149_Twain_VII_LOA_791109 11/8/11 7:24 PM Page 22 The Library of America • Story of the Week 2R2 eprinted from Mark Tawa tinr: aAm Trpa mapb Arboroaad, Following the Equator, Other Travels (The Library of America, $"#"), pages $$ –$&. enjoyed m© yC dopeyferiagth at s$ "m#"u cLhit earsa rayn Cy llaosswic sw ohf itthee pUe.oS.p, lIen c.ould have doneO. rTighineayll yc raapnpeadre tdh aesi rt hnee ecnkds oafn cdh alpatuegr h$ eadn da ta llm oef ,c h(faoprte ar %r aven can laugh, just likein aA mTraanm,p) Athbreoya d sq(#u'a'"ll)e.d insulting remarks after me as long as they could see me. They were nothing but ravens— I knew that,— what they thought about me could be a matter of noJ icmons eBquaeknceer,—’s aBndl uyeet -wJhaeyn eYveanr an raven shouts after you, “What a hat!” “O, pull down your vest!” and that sort of thing, it hurts you and humiliates you, and there is no getting around it with fine reasoning and pretty arguments. Animals talk to each other, of course. There can be no ques - tion about that; but I suppose there are very few people who can under stand them. I never knew but one man who could. I knew he could, however, because he told me so himself. He was a middle-aged, simple-hearted miner who had lived in a lonely corner of California, among the woods and mountains, a good many years, and had studied the ways of his only neigh - bors, the beasts and the birds, until he believed he could accu - rately translate any remark which they made.