Evidence for Vocal Learning by a Scrub Jay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Scrub-Jay Funerals: Cacophonous Aggregations in Response to Dead Conspecifics

Animal Behaviour 84 (2012) 1103e1111 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Western scrub-jay funerals: cacophonous aggregations in response to dead conspecifics T. L. Iglesias a,b,*, R. McElreath a,c, G. L. Patricelli a,b a Animal Behavior Graduate Group, University of California Davis, Davis, CA, U.S.A. b Department of Evolution and Ecology, University of California Davis, Davis, CA, U.S.A. c Department of Anthropology, University of California Davis, Davis, CA, U.S.A. article info All organisms must contend with the risk of injury or death; many animals reduce this danger by Article history: assessing environmental cues to avoid areas of elevated risk. However, little is known about how Received 23 October 2011 organisms respond to one of the most salient visual cues of risk: a dead conspecific. Here we show that Initial acceptance 16 January 2012 the sight of a dead conspecific is sufficient to induce alarm calling and subsequent risk-reducing Final acceptance 25 July 2012 behavioural modification in western scrub-jays, Aphelocoma californica, and is similar to the response Available online 27 August 2012 to a predator (a great horned owl, Bubo virginianus, model). Discovery of a dead conspecific elicits MS. number: A12-00867R vocalizations that are effective at attracting conspecifics, which then also vocalize, thereby resulting in a cacophonous aggregation. Presentations of prostrate dead conspecifics and predator mounts elicited Keywords: aggregations and hundreds of long-range communication vocalizations, while novel objects did not. In Aphelocoma californica contrast to presentations of prostrate dead conspecifics, presentations of a jay skin mounted in an bird upright, life-like pose elicited aggressive responses, suggesting the mounted scrub-jay was perceived to cacophonous aggregation cues of risk be alive and the prostrate jay was not. -

Corvids of Cañada

!!! ! CORVIDS OF CAÑADA COMMON RAVEN (Corvus corax) AMERICAN CROW (Corvus brachyrhyncos) YELLOW-BILLED MAGPIE (Pica nuttalli) STELLER’S JAY (Cyanocitta stelleri) WESTERN SCRUB-JAY Aphelocoma californica) Five of the ten California birds in the Family Corvidae are represented here at the Cañada de los Osos Ecological Reserve. Page 1 The Common Raven is the largest and can be found in the cold of the Arctic and the extreme heat of Death Valley. It has shown itself to be one of the most intelligent of all birds. It is a supreme predator and scavenger, quite sociable at certain times of the year and a devoted partner and parent with its mate. The American Crow is black, like the Raven, but noticeably smaller. Particularly in the fall, it may occur in huge foraging or roosting flocks. Crows can be a problem for farmers at times of the year and a best friend at other times, when crops are under attack from insects or when those insects are hiding in dried up leftovers such as mummified almonds. Crows know where those destructive navel orange worms are. Smaller birds do their best to harass crows because they recognize the threat they are to their eggs and young. Crows, ravens and magpies are important members of the highway clean-up crew when it comes to roadkills. The very attractive Yellow-billed Magpie tends to nest in loose colonies and forms larger flocks in late summer or fall. In the central valley of California, they can be a problem in almond and fruit orchards, but they also are adept at catching harmful insect pests. -

Migrational Movements of Blue Jays West of the 100Th Meridian

Migrational movementsof Blue Jays west of the 100th meridian Kimberly G. Smith Introduction Since the start of the bird-bandingprogram in movements-- in fall of 1939when 7350Blue Jays North America, the movements of Blue Jays passedHawk Mountain,Pennsylvania, in 16 days (Cyanocittacristata) have been of great interest. in late September(Broun 1941), and in fall of 1962 The first report of bird-bandingrecoveries by the when Blue Jaysinvaded Massachusetts (Nunneley BiologicalSurvey (Lincoln1924) listed 38 Blue Jay 1964). returns, all from the same stationat which they While investigatingthe range extensionof Blue were banded.The secondBiological Survey report Jaysinto westernNorth America(Smith 1978), ! (Lincoln 1927) listed 11 Blue Jays recovered at found that the breedingrange was slowlymoving placesremoved from the originalbanding station, westward,whereas the numberof winter sightings although219 of the 230reports still were returnsat in the PacificNorthwest was increasingdramati- the original station.Seven of these 11 recoveries cally.! was puzzledby the lack of winter sightings were within the samestate as the originalbanding in the Intermountainregion, and decided to ana- station,with the 4 othersall showingsouthward lyze the bandingrecoveries west of the 100thmer- movementsduring fall. Two of these recoveries constituted movements of over 667 kin. Over the idian to determine what pattern might emerge. Here, I presentthat analysis,which stronglysug- next 15 years,many long-distancemovements by geststhat most Blue Jay sightingsin the Pacific bandedBlue Jayswere reported(e.g., Whittle 1928, Northwestare individualsoriginating in western Anon. 1929, Roberts 1936, Stoner 1936), as were Canada rather than birds crossingthe Rockies sightingsof large massmovements or migrationsof from central United States. Blue Jays(e.g., Sherman 1931, Tyrrell 1934,Cottam 1937,Broun 1941,Lewis 1942). -

Observations on the Nest Behavior of the California Scrub Jay

NOTES OBSERVATIONS ON THE NEST BEHAVIOR OF THE CALIFORNIA SCRUB JAY To our knowledge no one has reported sustainedobservations of the nest behavior of the California Scrub Jay (Aphelocoma coemlescens).Incomplete observationsof one nest were reportedby Michenerand Michener(1945). On 28 March 1972 we found a completednest on a steepravine about five feet from the ground in a Toyon (Heteromeles arbu•folia) on the Point Reyes National Seashorein Marin Co., California. We watched the nest from a blind 30 feet away for 61 hoursand 53 minuteson the 2nd, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 10th, 11th, and 17th days after the first egg hatchedand once during the incubationperiod. Sincethe parents had been color bandedpreviously we knew that the female was 4 years old and the male at least 3. The female laid $ eggsand incubationlasted 18 days. Bent (1946) reported that incubationwas 14 to 16 days.The malewas not observedincubating. During the only sustainedobservation of adults during the incubationperiod, the female sat on the eggsfor 3 hours and 7 minutesbefore leaving the nest. During the 51 minutesshe was off the nest sheranged over most of the defendedterritory. The young hatched one at a time during a two-day period. The night after the last young hatched it rained and the next morning at 0600 the female was observed taking a dead nestlingfrom the nest. The last nestlingto hatch was noticeably smaller than the earlier ones;we assume,therefore, that becauseof the rain and becausethe youngestnestling was probably the weakest,that this nestlingdied. When the eggshatched the male began to bring food to the female and the nestlings.Upon arrivingat the nest he would poke his beak asfar ashe couldinto the female's mouth transferring some of his food to her. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Rules

21282 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR United States and the Government of United States or U.S. territories as a Canada Amending the 1916 Convention result of recent taxonomic changes; Fish and Wildlife Service between the United Kingdom and the (8) Change the common (English) United States of America for the names of 43 species to conform to 50 CFR Part 10 Protection of Migratory Birds, Sen. accepted use; and (9) Change the scientific names of 135 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; Treaty Doc. 104–28 (December 14, FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000] 1995); species to conform to accepted use. (2) Mexico: Convention between the The List of Migratory Birds (50 CFR RIN 1018–BC67 United States and Mexico for the 10.13) was last revised on November 1, Protection of Migratory Birds and Game 2013 (78 FR 65844). The amendments in General Provisions; Revised List of this rule were necessitated by nine Migratory Birds Mammals, February 7, 1936, 50 Stat. 1311 (T.S. No. 912), as amended by published supplements to the 7th (1998) AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Protocol with Mexico amending edition of the American Ornithologists’ Interior. Convention for Protection of Migratory Union (AOU, now recognized as the American Ornithological Society (AOS)) ACTION: Final rule. Birds and Game Mammals, Sen. Treaty Doc. 105–26 (May 5, 1997); Check-list of North American Birds (AOU 2011, AOU 2012, AOU 2013, SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and (3) Japan: Convention between the AOU 2014, AOU 2015, AOU 2016, AOS Wildlife Service (Service), revise the Government of the United States of 2017, AOS 2018, and AOS 2019) and List of Migratory Birds protected by the America and the Government of Japan the 2017 publication of the Clements Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) by for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Checklist of Birds of the World both adding and removing species. -

California Native Birds

California Native Birds De Anza College Biology 6C: Ecology and Evoluon Bruce Heyer Red Tailed Hawk (Buteo Jamaicensis) Accipitridae (hawks) • Broad, rounded wings and a short, wide tail. • The tail is usually pale below and cinnamon‐red above • Flies in wide circles high above ground. • Brown above, and pale underbelly • Habitat: In open country, perch on fences, poles, trees, etc. 1 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Cathardae (vultures) • Large dark birds, have a featherless red head and pale bill. Dark feathers (brown, look black from father). Have pale underside of feathers (“two‐ tone” appearance) • Commonly found in open areas. • Very few wing beats, characterisc soaring. California Quail Callipepla californica Phasianidae (partridges) • Plump, short‐necked game birds with a small head and bill. They fly on short, very broad wings. Both sexes have a comma‐ shaped topknot of feathers projecng forward from the forehead. • Adult males are rich gray and brown, with a black face outlined with bold white stripes. Females are a plainer brown and lack the facial markings. Both sexes have a paern of white, creamy, and chestnut scales on the belly. • Live in scrublands and desert areas. • Diet consists of seeds, some vegetaon, and insects 2 Mourning Dove Zenaida macroura Columbidae (doves) • Plump bodies, small bill and short legs. Pointed tail. Usually greyish‐tan with black spots on wings. White ps to tail feathers. • Beat wings rapidly, and powerfully. • Found everywhere. • Usually feeds on seeds. Rock Dove (Pigeon) Columba livia Columbidae (doves) • Larger than mourning doves, large bodies, small heads and feet. Wide, rounded tails and pointed wings. • Generally blue‐gray, with iridescent throat feathers, bright feet. -

Sonoma County Bird List

Sonoma County Bird List Benjamin D. Parmeter and Alan N. Wight October 23, 2018 This is a list of all of the bird species recorded in Sonoma County, California, United States as of the date shown above. A total of 456 species have been recorded. In addition, a record of Veery is currently being reviewed by the California Bird Records Committee and will be added to the Sonoma County list if accepted. The species names and order follow the eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2018 which is "based largely on decisions of the North American Checklist Committee (NACC), through the Fifty-ninth supplement to the American Ornithological Society’s Check-list of North American Birds (July 2018)." Anatidae (Ducks, Geese, and Waterfowl) Emperor Goose Anser canagicus Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ross's Goose Anser rossii Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Brant Branta bernicla Cackling Goose Branta hutchinsii Canada Goose Branta canadensis Tundra Swan Cygnus columbianus Wood Duck Aix sponsa Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Gadwall Mareca strepera Eurasian Wigeon Mareca penelope American Wigeon Mareca americana Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Northern Pintail Anas acuta Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Canvasback Aythya valisineria Redhead Aythya americana Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula Greater Scaup Aythya marila Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Steller's Eider Polysticta stelleri King Eider Somateria spectabilis Harlequin Duck Histrionicus histrionicus -

The Evolution of Delayed Dispersal in Cooperative Breeders

The Evolution of Delayed Dispersal in Cooperative Breeders Walter D. Koenig; Frank A. Pitelka; William J. Carmen; Ronald L. Mumme; Mark T. Stanback The Quarterly Review of Biology, Vol. 67, No. 2. (Jun., 1992), pp. 111-150. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0033-5770%28199206%2967%3A2%3C111%3ATEODDI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-D The Quarterly Review of Biology is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

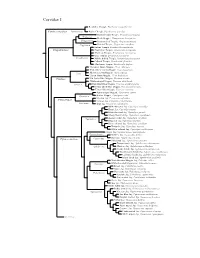

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Blue Jay, Vol.50, Issue 1

FALL FOOD OF THE EASTERN SCREECH-OWL IN MANITOBA KURT M. MAZUR, 15 Attache Place, Winnipeg, Manitoba. R2V 3L3 The Eastern Screech-owl is one of site. Through examination of the prey the most widespread owls in North remains, an owl’s diet can be ac¬ America.4 It ranges from the Gulf of curately quantified.6,8 Mexico north to southern Manitoba, and from Montana to the east coast Starting 13 October 1990, 40 nest of the United States.14 This small boxes were checked for prey (20-24 cm) highly nocturnal owl has remains. Five of these contained pel¬ a diet that is quite varied over its lets and/or bones and feathers, range and throughout the presumably the prey of the resident season.1,4,5,11'12,15,16,18 Several screech-owl. These five boxes, and studies of the Eastern Screech-owl’s the surrounding areas, were checked diet have been published, but none once a week from 13 October to 4 from the northern edge of its November 1990. range.5,15,16,18 Reports of Eastern Screech-owls in Manitoba occur as Prey were identified to species far north as Riding Mountain National when possible. Mean individual prey Park.1 weight was estimated by taking the average weight of five individuals of This study was done near Win¬ each species from the same time of nipeg in autumn, a time when num¬ year, based on data from Manitoba bers and types of prey available are specimen collections.9 From these changing.7,13,16 The study area was individual prey weights a percent in La Barriere Park along the La total weight was calculated for the Salle River, just south of Winnipeg. -

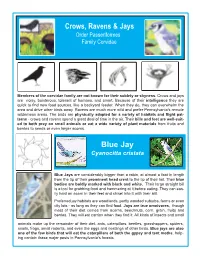

Crows, Ravens, and Jays

Crows, Ravens & Jays Order Passeriformes Family Corvidae Members of the corvidae family are not known for their sublety or shyness. Crows and jays are noisy, boisterous, tolerant of humans, and smart. Because of their intelligence they are quick to find new food sources, like a backyard feeder. When they do, they can overwhelm the area and drive other birds away. Ravens are much more wild and prefer Pennsylvania’s remote wilderness areas. The birds are physically adapted for a variety of habitats and flight pat- terns - crows and ravens spend a great deal of time in the air. Their bills and feet are well-suit- ed to both prey on small animals or eat a wide variety of plant materials from fruits and berries to seeds or even larger acorns. Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata Blue Jays are considerably bigger than a robin, at almost a foot in length from the tip of their prominent head crest to the tip of their tail. Their blue bodies are boldly marked with black and white. Their large straight bill is a tool for grabbing food and hammering at it before eating. They can eas- ily hold an acorn in their feet and chisel into it with their bill. Preferred jay habitats are woodlands, partly wooded suburbs, farms or even city lots - as long as they can find food. Jays are true omnivores, though most of their diet comes from acorns, beechnuts, corn, grain, fruits and berries. They will eat carrion when they find it. All kinds of insects and small animals make up the remainder of their diet: ants, caterpillars, beetles, grasshoppers, spiders, snails, frogs, small rodents, and even the eggs and nestlings of other birds. -

Alaja & Mikkola-33-37

Albinism in the Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa) and Other Owls Pentti Alaja and Heimo Mikkola1 Abstract.—An incomplete albino Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa) was observed in Vesanto and Kajaani, Finland, 1994-1995. The literature pertaining to albinism in owls indicates that total and incomplete albinism has only been reported in 13 different owl species, the Great Gray Owl being the only species with more than five records. Thus six to seven incomplete albino Great Grays have been recorded since 1980 in Canada, Finland, and the United States. ___________________ It would seem that most animals produce Partial albinism may result from injury, physio- occasional albinos; some species do so quite logical disorder, diet, or circulatory problems. frequently whilst this phenomenon is much This type of albinism is most frequently rarer in others. Although albinism in most observed. It is important to note that white avian families is frequently recorded, we know plumage is not necessarily proof of albinism. of very few abnormally white owls. Thus the motive of this paper is to assemble as complete Adult Snowy Owls (Nyctea scandiaca) are a record as possible of white or light color primarily white, but have their feather color mutations of owls which exist or have been derived from a schemochrome feather structure recorded. which possesses little or no pigment. Light reflects within the feather structure and GENETICS OF ALBINISM produces the white coloration (Holt et al. 1995). Albinism is derived from a recessive gene which ALBINISM IN THE GREAT GRAY OWLS inhibits the enzyme tyrosinase. Tyrosine, an amino acid, synthesizes the melanin that is the An extremely light and large Great Gray Owl basis of many avian colors (Holt et al.