Nuclear Titin Interacts with A- and B-Type Lamins in Vitro and in Vivo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lamin-Related Congenital Muscular Dystrophy Alters Mechanical Signaling and Skeletal Muscle Growth

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Lamin-Related Congenital Muscular Dystrophy Alters Mechanical Signaling and Skeletal Muscle Growth Daniel J. Owens 1,2 , Julien Messéant 1, Sophie Moog 3, Mark Viggars 2, Arnaud Ferry 1,4, Kamel Mamchaoui 1,5, Emmanuelle Lacène 5 , Norma Roméro 5,6, Astrid Brull 1 , Gisèle Bonne 1 , Gillian Butler-Browne 1 and Catherine Coirault 1,* 1 Center for Research in Myology, Sorbonne Université, INSERM UMRS_974, 75013 Paris, France; [email protected] (D.J.O.); [email protected] (J.M.); [email protected] (A.F.); [email protected] (K.M.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (G.B.-B.) 2 Research Institute for Sport and Exercise Science, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L3 3AF, UK; [email protected] 3 Inovarion, 75005 Paris, France; [email protected] 4 Université de Paris, 75006 Paris, France 5 Neuromuscular Morphology Unit, Institute of Myology, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, 75013 Paris, France; [email protected] (E.L.); [email protected] (N.R.) 6 APHP, Reference Center for Neuromuscular Disorders, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Institute of Myology, 75013 Paris, France * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-1-1-4216-5708 Abstract: Laminopathies are a clinically heterogeneous group of disorders caused by mutations in the LMNA gene, which encodes the nuclear envelope proteins lamins A and C. The most frequent diseases associated with LMNA mutations are characterized by skeletal and cardiac involvement, and include autosomal dominant Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD), limb-girdle muscular Citation: Owens, D.J.; Messéant, J.; dystrophy type 1B, and LMNA-related congenital muscular dystrophy (LMNA-CMD). -

ARVC-Variants.Pdf

Updated gene list responsible for ARVC/D pathology Subtype Gene Location Reference ARVC1 TGFB3 14q24.3 Beffagna G, Occhi G, Nava A, et al. Regulatory mutations in transforming growth factor-beta3 gene cause arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 1. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:366–73. ARVC2 RYR2 1q43 Tiso N, Stephan DA, Nava A, et al. Identification of mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene in families affected with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 2 (ARVD2). Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:189–94. ARVC3 Unknown 14q12-q22 Severini GM, Krajinovic M, Pinamonti B, et al. A new locus for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia on the long arm of chromosome 14. Genomics. 1996;31:193–200. ARVC4 TTN 2q32.1-q32.3 Taylor M, Graw S, Sinagra G, et al. Genetic variation in titin in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy-overlap syndromes. Circulation. 2011;124:876–85. ARVC5 TMEM43 3p25.1 Merner ND, Hodgkinson KA, Haywood AF, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 5 is a fully penetrant, lethal arrhythmic disorder caused by a missense mutation in the TMEM43 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:809–21. ARVC6 Unknown 10p14-p12 Li D, Ahmad F, Gardner MJ, et al. The locus of a novel gene responsible for arrhythmogenic right- ventricular dysplasia characterized by early onset and high penetrance maps to chromosome 10p12-p14. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:148–56. ARVC7 DES 2q35 Klauke B, Kossmann S, Gaertner A, et al. De novo desmin-mutation N116S is associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4595–607. -

Genetic Mutations and Mechanisms in Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Genetic mutations and mechanisms in dilated cardiomyopathy Elizabeth M. McNally, … , Jessica R. Golbus, Megan J. Puckelwartz J Clin Invest. 2013;123(1):19-26. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI62862. Review Series Genetic mutations account for a significant percentage of cardiomyopathies, which are a leading cause of congestive heart failure. In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), cardiac output is limited by the thickened myocardium through impaired filling and outflow. Mutations in the genes encoding the thick filament components myosin heavy chain and myosin binding protein C (MYH7 and MYBPC3) together explain 75% of inherited HCMs, leading to the observation that HCM is a disease of the sarcomere. Many mutations are “private” or rare variants, often unique to families. In contrast, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is far more genetically heterogeneous, with mutations in genes encoding cytoskeletal, nucleoskeletal, mitochondrial, and calcium-handling proteins. DCM is characterized by enlarged ventricular dimensions and impaired systolic and diastolic function. Private mutations account for most DCMs, with few hotspots or recurring mutations. More than 50 single genes are linked to inherited DCM, including many genes that also link to HCM. Relatively few clinical clues guide the diagnosis of inherited DCM, but emerging evidence supports the use of genetic testing to identify those patients at risk for faster disease progression, congestive heart failure, and arrhythmia. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/62862/pdf Review series Genetic mutations and mechanisms in dilated cardiomyopathy Elizabeth M. McNally, Jessica R. Golbus, and Megan J. Puckelwartz Department of Human Genetics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA. Genetic mutations account for a significant percentage of cardiomyopathies, which are a leading cause of conges- tive heart failure. -

Lamin A/C Cardiomyopathy: Implications for Treatment

Current Cardiology Reports (2019) 21:160 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-019-1224-7 MYOCARDIAL DISEASE (A ABBATE AND G SINAGRA, SECTION EDITORS) Lamin A/C Cardiomyopathy: Implications for Treatment Suet Nee Chen1 & Orfeo Sbaizero1,2 & Matthew R. G. Taylor1 & Luisa Mestroni1 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose of Review The purpose of this review is to provide an update on lamin A/C (LMNA)-related cardiomyopathy and discuss the current recommendations and progress in the management of this disease. LMNA-related cardiomyopathy, an inherited autosomal dominant disease, is one of the most common causes of dilated cardiomyopathy and is characterized by steady progression toward heart failure and high risks of arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Recent Findings We discuss recent advances in the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of the disease including altered cell biomechanics, which may represent novel therapeutic targets to advance the current management approach, which relies on standard heart failure recommendations. Future therapeutic approaches include repurposed molecularly directed drugs, siRNA- based gene silencing, and genome editing. Summary LMNA-related cardiomyopathy is the focus of active in vitro and in vivo research, which is expected to generate novel biomarkers and identify new therapeutic targets. LMNA-related cardiomyopathy trials are currently underway. Keywords Lamin A/C gene . Laminopathy . Heart failure . Arrhythmias . Mechanotransduction . P53 . CRISPR–Cas9 therapy Introduction functions, including maintaining nuclear structural integrity, regulating gene expression, mechanosensing, and Mutations in the lamin A/C gene (LMNA)causelaminopathies, mechanotransduction through the lamina-associated proteins a heterogeneous group of inherited disorders including muscu- [6–11]. -

Nesprins: from the Nuclear Envelope and Beyond

expert reviews http://www.expertreviews.org/ in molecular medicine Nesprins: from the nuclear envelope and beyond Dipen Rajgor and Catherine M. Shanahan* Nuclear envelope spectrin-repeat proteins (Nesprins), are a novel family of nuclear and cytoskeletal proteins with rapidly expanding roles as intracellular scaffolds and linkers. Originally described as proteins that localise to the nuclear envelope (NE) and establish nuclear-cytoskeletal connections, nesprins have now been found to comprise a diverse spectrum of tissue specific isoforms that localise to multiple sub-cellular compartments. Here, we describe how nesprins are necessary in maintaining cellular architecture by acting as essential scaffolds and linkers at both the NE and other sub-cellular domains. More importantly, we speculate how nesprin mutations may disrupt tissue specific nesprin scaffolds and explain the tissue specific nature of many nesprin-associated diseases, including laminopathies. The eukaryotic cytoplasm contains three major composed of three α-helical bundles with a left- types of cytoskeletal filaments: Filamentous- handed twist, and its primary function is to actin (F-actin), microtubules (MTs) and provide docking sites for proteins and other intermediate filaments (IFs). These components higher order complexes (Refs 3, 4). Although are organised in a manner that provides the cell most SR proteins contain CHDs, some possess with an internal framework fundamental for motifs which can interact with other cytoskeletal many processes, such as controlling cellular components, allowing linkage of SR-associated shape, polarity, adhesion and migration, complexes to filamentous structures other than cytokinesis, inter- and intracellular F-actin. In addition, these motifs allow cross- Nesprins: from the nuclear envelope and beyond communication and trafficking of organelles, linking between different filaments and dynamic vesicles, proteins and RNA (Refs 1, 2). -

Hippocampal LMNA Gene Expression Is Increased in Late-Stage Alzheimer’S Disease

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Hippocampal LMNA Gene Expression is Increased in Late-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease Iván Méndez-López 1,2,*,†, Idoia Blanco-Luquin 1,†, Javier Sánchez-Ruiz de Gordoa 1,3, Amaya Urdánoz-Casado 1, Miren Roldán 1, Blanca Acha 1, Carmen Echavarri 1,4, Victoria Zelaya 5, Ivonne Jericó 3 and Maite Mendioroz 1,3,* 1 Neuroepigenetics Laboratory-Navarrabiomed, Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, Universidad Pública de Navarra (UPNA), IdiSNA (Navarra Institute for Health Research), Pamplona, Navarra 31008, Spain; [email protected] (I.B.-L.); [email protected] (J.S.-R.d.G.); [email protected] (A.U.-C.); [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (B.A.); [email protected] (C.E.) 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital García Orcoyen, Estella 31200, Spain 3 Department of Neurology, Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra- IdiSNA (Navarra Institute for Health Research), Pamplona, Navarra 31008, Spain; [email protected] 4 Hospital Psicogeriátrico Josefina Arregui, Alsasua, Navarra 31800, Spain 5 Department of Pathology, Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra- IdiSNA (Navarra Institute for Health Research), Pamplona, Navarra 31008, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.M.-L.); [email protected] (M.M.); Tel.: +34-848-422677 (I.M.-L.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 14 February 2019; Published: 18 February 2019 Abstract: Lamins are fibrillary proteins that are crucial in maintaining nuclear shape and function. Recently, B-type lamin dysfunction has been linked to tauopathies. However, the role of A-type lamin in neurodegeneration is still obscure. -

Eleven Daughters of NANOG

Genomics 84 (2004) 229–238 www.elsevier.com/locate/ygeno Eleven daughters of NANOG$ H. Anne F. Booth and Peter W.H. Holland* Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PS, UK Received 4 December 2003; accepted 25 February 2004 Available online 15 April 2004 Abstract Nanog is a recently discovered ANTP class homeobox gene. Mouse Nanog is expressed in the inner cell mass and in embryonic stem cells and has roles in self-renewal and maintenance of pluripotency. Here we describe the location, genomic organization, and relative ages of all human NANOG pseudogenes, comprising ten processed pseudogenes and one tandem duplicate. These are compared to the original, intact human NANOG gene. Eleven is an unusually high number of pseudogenes for a homeobox gene and must reflect expression in the human germ line. A pseudogene orthologous to NANOGP4 was found in chimpanzee and an expressed pseudogene in macaque. Examining pseudogenes of differing ages gives insight into pseudogene decay, which involves an excess of deletion mutations over insertions. The mouse genome has two processed pseudogenes, which are not clear orthologues of the primate pseudogenes. D 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Homeobox; Pseudogene; Molecular evolution; Enk Homeobox genes are characterized by possession of a Mitsui and colleagues [3] identified a single human recognizable 60- or 63-amino-acid motif within the orthologue of the mouse Nanog gene, mapping to encoded protein. The homeobox gene superfamily is 12p13.31. extremely diverse, particularly within animal genomes, As of February 2004, the Mouse Genome Informatics and can be subdivided into several major classes, each web site and National Center for Biotechnology Information containing numerous gene families. -

Abnormal Nuclear Shape and Impaired Mechanotransduction in Emerin

JCB: ARTICLE Abnormal nuclear shape and impaired mechanotransduction in emerin-deficient cells Jan Lammerding,1 Janet Hsiao,2 P. Christian Schulze,1 Serguei Kozlov,3 Colin L. Stewart,3 and Richard T. Lee1 1Cardiovascular Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115 2HST Division, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 3Cancer and Developmental Biology Lab, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD 21702 mery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy can be caused type cells in cellular strain experiments, and the integrity by mutations in the nuclear envelope proteins lamin of emerin-deficient nuclear envelopes appeared normal E A/C and emerin. We recently demonstrated that in a nuclear microinjection assay. Interestingly, expres- A-type lamin-deficient cells have impaired nuclear me- sion of mechanosensitive genes in response to mechani- chanics and altered mechanotransduction, suggesting cal strain was impaired in emerin-deficient cells, and two potential disease mechanisms (Lammerding, J., P.C. prolonged mechanical stimulation increased apoptosis in Schulze, T. Takahashi, S. Kozlov, T. Sullivan, R.D. Kamm, emerin-deficient cells. Thus, emerin-deficient mouse em- C.L. Stewart, and R.T. Lee. 2004. J. Clin. Invest. 113: bryo fibroblasts have apparently normal nuclear me- 370–378). Here, we examined the function of emerin on chanics but impaired expression of mechanosensitive nuclear mechanics and strain-induced signaling. Emerin- genes in response to strain, suggesting that emerin muta- deficient mouse embryo fibroblasts have -

Deficiencies in Lamin B1 and Lamin B2 Cause Neurodevelopmental Defects and Distinct Nuclear Shape Abnormalities in Neurons

M BoC | ARTICLE Deficiencies in lamin B1 and lamin B2 cause neurodevelopmental defects and distinct nuclear shape abnormalities in neurons Catherine Coffiniera, Hea-Jin Jungb, Chika Nobumoria, Sandy Changa, Yiping Tua, Richard H. Barnes IIa, Yuko Yoshinagac, Pieter J. de Jongc, Laurent Vergnesd, Karen Reued, Loren G. Fonga, and Stephen G. Younga,d aDepartment of Medicine and bMolecular Biology Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095; cChildren’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, CA 94609; dDepartment of Human Genetics, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095 ABSTRACT Neuronal migration is essential for the development of the mammalian brain. Monitoring Editor Here, we document severe defects in neuronal migration and reduced numbers of neurons in Thomas Michael Magin lamin B1–deficient mice. Lamin B1 deficiency resulted in striking abnormalities in the nuclear University of Leipzig shape of cortical neurons; many neurons contained a solitary nuclear bleb and exhibited an Received: Jun 13, 2011 asymmetric distribution of lamin B2. In contrast, lamin B2 deficiency led to increased numbers Revised: Sep 9, 2011 of neurons with elongated nuclei. We used conditional alleles for Lmnb1 and Lmnb2 to create Accepted: Sep 23, 2011 forebrain-specific knockout mice. The forebrain-specificLmnb1- and Lmnb2-knockout models had a small forebrain with disorganized layering of neurons and nuclear shape abnormalities, similar to abnormalities identified in the conventional knockout mice. A more severe pheno- type, complete atrophy of the cortex, was observed in forebrain-specific Lmnb1/Lmnb2 double-knockout mice. This study demonstrates that both lamin B1 and lamin B2 are essential for brain development, with lamin B1 being required for the integrity of the nuclear lamina, and lamin B2 being important for resistance to nuclear elongation in neurons. -

Doubly Heterozygous LMNA and TTN Mutations Revealed by Exome Sequencing in a Severe Form of Dilated Cardiomyopathy

European Journal of Human Genetics (2013) 21, 1105–1111 & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/13 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Doubly heterozygous LMNA and TTN mutations revealed by exome sequencing in a severe form of dilated cardiomyopathy Roberta Roncarati1,2, Chiara Viviani Anselmi2, Peter Krawitz3,4,5, Giovanna Lattanzi6, Yskert von Kodolitsch7, Andreas Perrot8,9, Elisa di Pasquale2,10, Laura Papa2, Paola Portararo2, Marta Columbaro6, Alberto Forni11, Giuseppe Faggian*,11, Gianluigi Condorelli*,1,12 and Peter N Robinson*,3,4,5 Familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a heterogeneous disease; although 30 disease genes have been discovered, they explain only no more than half of all cases; in addition, the causes of intra-familial variability in DCM have remained largely unknown. In this study, we exploited the use of whole-exome sequencing (WES) to investigate the causes of clinical variability in an extended family with 14 affected subjects, four of whom showed particular severe manifestations of cardiomyopathy requiring heart transplantation in early adulthood. This analysis, followed by confirmative conventional sequencing, identified the mutation p.K219T in the lamin A/C gene in all 14 affected patients. An additional variant in the gene for titin, p.L4855F, was identified in the severely affected patients. The age for heart transplantation was substantially less for LMNA:p.K219T/ TTN:p.L4855F double heterozygotes than that for LMNA:p.K219T single heterozygotes. Myocardial specimens of doubly heterozygote individuals showed increased nuclear length, sarcomeric disorganization, and myonuclear clustering compared with samples from single heterozygotes. In conclusion, our results show that WES can be used for the identification of causal and modifier variants in families with variable manifestations of DCM. -

Supplementary Table 1

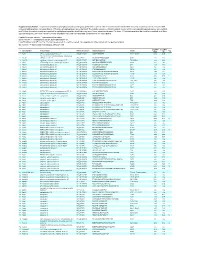

Supplementary Table 1. Large-scale quantitative phosphoproteomic profiling was performed on paired vehicle- and hormone-treated mTAL-enriched suspensions (n=3). A total of 654 unique phosphopeptides corresponding to 374 unique phosphoproteins were identified. The peptide sequence, phosphorylation site(s), and the corresponding protein name, gene symbol, and RefSeq Accession number are reported for each phosphopeptide identified in any one of three experimental pairs. For those 414 phosphopeptides that could be quantified in all three experimental pairs, the mean Hormone:Vehicle abundance ratio and corresponding standard error are also reported. Peptide Sequence column: * = phosphorylated residue Site(s) column: ^ = ambiguously assigned phosphorylation site Log2(H/V) Mean and SE columns: H = hormone-treated, V = vehicle-treated, n/a = peptide not observable in all 3 experimental pairs Sig. column: * = significantly changed Log 2(H/V), p<0.05 Log (H/V) Log (H/V) # Gene Symbol Protein Name Refseq Accession Peptide Sequence Site(s) 2 2 Sig. Mean SE 1 Aak1 AP2-associated protein kinase 1 NP_001166921 VGSLT*PPSS*PK T622^, S626^ 0.24 0.95 PREDICTED: ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A 2 Abca12 (ABC1), member 12 XP_237242 GLVQVLS*FFSQVQQQR S251^ 1.24 2.13 3 Abcc10 multidrug resistance-associated protein 7 NP_001101671 LMT*ELLS*GIRVLK T464, S468 -2.68 2.48 4 Abcf1 ATP-binding cassette sub-family F member 1 NP_001103353 QLSVPAS*DEEDEVPVPVPR S109 n/a n/a 5 Ablim1 actin-binding LIM protein 1 NP_001037859 PGSSIPGS*PGHTIYAK S51 -3.55 1.81 6 Ablim1 actin-binding -

Mechanosensing Defects and YAP-Signaling in LMNA-Related Congenital Muscular Dystrophy

Mechanosensing defects and YAP-signaling in LMNA-related congenital muscular dystrophy Dissertation in fulfillment of the requirements for the Joint Degree (Cotutelle) “Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.)” integrated in the International Graduate School for Myology “MyoGrad” in the Department of Biology, Chemistry, Pharmacy at Freie Universität Berlin and in Cotutelle Agreement with the Ecole Doctorale 515 “Complexité du Vivant” at the Université Pierre et Marie Curie Paris 6 Submitted by Martina Fischer Supervised by Catherine Coirault and Prof. Dr. Petra Knaus Thesis defense: June 28th, 2017 Thesis jury: Thesis supervisor, UPMC: Catherine Coirault, PhD Thesis supervisor, first reviewer of Freie Universität Berlin: Prof. Dr. Petra Knaus Reviewer UPMC: Jean-Thomas Vilquin, PhD Second reviewer, Freie Universität Berlin: Prof. Dr. Sigmar Stricker External Expert: Prof. Dr. Henning Wackerhage External Expert: Prof. Dr. Michael Gotthardt External Expert: Prof. Dr. Markus Schülke-Gerstenfeld Postdoctoral Fellow, Freie Universität Berlin: Dr. Maria Reichenbach ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisors Catherine Coirault and Prof. Dr. Petra Knaus for the continuous support of my PhD study, for their example, effort and knowledge. Their guidance was essential in all the time of my research and writing. Besides my advisors, I would like to thank the members of my former thesis committee and todays defense committee: Prof. Dr. Sigmar Stricker, Prof. Dr. Michael Gotthardt, Prof. Dr. Henning Wackerhage, Jean-Thomas Vilquin, Dr. Maria Reichenbach, Danièle Lacasa, Athanassia Sotiropoulos, Sigolène Meilhac and Dr. Christian Hiepen for their insightful comments and support. I also own thanks to the founders and coordinators of MyoGrad, especially Gisèle Bonne and Simone Spuler for creating this fruitful environment.