Mining, Foreignness, and Friendship in Contemporary Mongolia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reaching for Divinity the Role of Herakles in Relation to Dexiosis

Reaching for Divinity The role of Herakles in relation to dexiosis Florien Plasschaert Utrecht University RMA ANCIENT, MEDIEVAL, AND RENAISSANCE STUDIES thesis under the supervision of dr. R. Strootman | prof. L.V. Rutgers Cover Photo: Dexiosis relief of Antiochos I of Kommagene with Herakles at Arsameia on the Nymphaion. Photograph by Stefano Caneva, distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license. 1 Reaching for Divinity The role of Herakles in relation to dexiosis Florien Plasschaert Utrecht 2017 2 Acknowledgements The completion of this master thesis would not have been possible were not it for the advice, input and support of several individuals. First of all, I owe a lot of gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Rolf Strootman, whose lectures not only inspired the subject for this thesis, but whose door was always open in case I needed advice or felt the need to discuss complex topics. With his incredible amount of knowledge on the Hellenistic Period provided me with valuable insights, yet always encouraged me to follow my own view on things. Over the course of this study, there were several people along the way who helped immensely by providing information, even if it was not yet published. Firstly, Prof. Dr. Miguel John Versluys, who was kind enough to send his forthcoming book on Nemrud Dagh, an important contribution to the information on Antiochos I of Kommagene. Secondly, Prof. Dr. Panagiotis Iossif who even managed to send several articles in the nick of time to help my thesis. Lastly, the National Numismatic Collection department of the Nederlandse Bank, to whom I own gratitude for sending several scans of Hellenistic coins. -

Mongolian European Chamber Of

MONGOL Since 1991 the MESSENGER 500 ¥ No. 07-08 (1076-1077) MONGOLIA’S FIRST ENGLISH WEEKLY PUBLISHED BY MONTSAME NEWS AGENCY Friday, February 17, 2012 Mongolia Economic Happy Tsagaan Sar! Forum planned for early March The Mongolian Economic Forum 2012 will run on March 5-6. At a February 10 press conference, organizers of the forum reported about the preparations and measures for the forum. As of information given by MP S. Oyun; Deputy Finance Minister Ch.Gankhuyag; Ch.Khashchuluun, head of the National Development and Innovation Committee; and P.Tsagaan, senior advisor to the President, the forum that is to be organized for the third time, will run this year under the motto ‘Together for Development’. The forum will have sub-meetings under themes on economic development, social policy and competitiveness, and bring together over 1000 foreign and domestic participants. During the forum, it is planned to publicly introduce Mongolia’s development forum until 2021 issued by Open Society. MP S. Oyun said, “In reality, why isn’t poverty decreasing while the economy has grown over the past five or six years. We believe that issues on how to decrease poverty and what should be done for the fruits of economic growth to improve livelihoods will develop into hot discussions during the forum. For instance, the statistical figures on poverty percentages are very confusing. The National Statistical Committee evaluates the poverty rate at 39 percent while the World Bank says it is lower using a different methodology to evaluate poverty. Therefore, -

State of Indiana Motorcycle Operators Manual

WWW.RIDESAFEINDIANA.COM Motorcycle Operator Manual JANUARY 1, 2017 BMV0005 2ND EDITION MOTORCYCLES MAKE SENSE – PREFACE SO DOES PROFESSIONAL TRAINING Welcome to the Seventeenth Edition This latest edition has undergone Motorcycles are inexpensive to operate, fun to ride and easy to park. of the MSF Motorcycle Operator Manual significant improvements, and contains Unfortunately, many riders never learn critical skills needed to ride safely. (MOM). Operating a motorcycle safely new, more in-depth information, Professional training for beginning and experienced riders prepares them for in traffic requires special skills and designed to: real-world traffic situations. Motorcycle Safety Foundation RiderCoursesSM teach and knowledge. The Motorcycle Safety • Guide riders in preparing to ride improve such skills as: Foundation (MSF) has made this manual safely available to help novice motorcyclists • Effective turning • Braking maneuvers • Protective apparel selection reduce their risk of having a crash. The • Develop effective street strategies • Obstacle avoidance • Traffic strategies • Maintenance manual conveys essential safe riding • Give riders more comprehensive information and has been designed understanding of safe group riding For the basic or experienced RiderCourse nearest you, for use in licensing programs. While practices designed for the novice, all motorcyclists call toll free: 800.446.9227 • Describe in detail best practices for can benefit from the information this or visit msf-usa.org carrying passengers and cargo manual contains. In promoting improved licensing The Motorcycle Safety Foundation’s (MSF) purpose is to improve the safety The original Motorcycle Operator of motorcyclists on the nation’s streets and highways. In an attempt to reduce programs, the MSF works closely with Manual was developed by the National motorcycle crashes and inju ries, the Foundation has programs in rider education, state licensing agencies. -

IPMBA News Vol. 18 No. 1 Winter 2009

Product Guide Winter 2009 ipmbaNewsletter of the International Police newsMountain Bike Association IPMBA: Promoting and Advocating Education and Organization for Public Safety Bicyclists. Vol. 18, No. 1 IPMBA Goes to Guyana Inauguration Action by Maureen Becker Executive Director by Mike Johnston, PCI #107 (as told to Maureen Becker) University of Utah Police/Hogle Zoo Security t may have been cold, but the freezing temperatures had no effect on the hen the notice came out from the IPMBA office enthusiasm of the crowd that gathered in Baltimore’s War Memorial Plaza on about a training opportunity in Guyana, I was I Saturday, January 17. President-elect Barack Obama’s train was due to arrive at intrigued. The idea of teaching a course in Penn Station at 4:00pm, and Baltimore was ready. W South America was oddly appealing, so my teaching Initial projections for the crowd were between 100,000 and 150,000. The health partner, Gary McLaughlin, and I decided to check it commissioner urged the old, the young, and the vulnerable to stay home and watch out. Although we did not what to expect, the posting the festivities on TV. Highway signs announced that the event was at capacity by assured us that as a former British colony, Guyana is 1:00pm. The cautionary language must have dissuaded a lot of people, as attendance South America’s only English-speaking nation, so we was later estimated at 40,000. Those 40,000 people, however, were packed into an knew that language would not be a problem. area described as accommodating only 30,000. -

House System

THE RON CLARK ACADEMY House System BRAND GUIDELINES Version 01, Summer 2019 The Ron Clark Academy House System is a dynamic, exciting, and proven way to create a positive climate and culture for students and staff. Using RCA’s methods will help your school or district confidently implement processes that build character, relationships, and school spirit. Our guidelines are designed to give you a streamlined framework that can be applied to any type of learning environment. The Ron Clark Academy Table of Contents The House system House System in a Nutshell 05 The House System 1. ON THE FIRST DAY of the school year, 05 Why the House System? Why the House System? incoming 5th graders (or the youngest students in your class, school, or 07 Words of Wisdom Implementing the RCA House System with your class, grade, district) spin a wheel to be sorted into 09 Sorting into Houses school, or district will provide benefits that will deeply impact a House at random. students and teachers alike. 2. STUDENTS REMAIN IN THIS GROUP until they graduate. 11 The Four Houses of every 15 Altruismo Students and teachers at schools where the House System has been put in place 3. EACH HOUSE IS COMPOSED have raved about the impact it has had on the educational experience. Children child in the school — teachers, faculty, 21 Amistad have noted such things as how it has helped them to form friendships and create and staff — allowing students to 27 Isibindi closer bonds with their peers. Teachers have noted how students perform at higher socialize with one another across 33 Rêveur levels when points are assigned and their peers are cheering them on. -

Food, Grooming, and Cultural Pathways of Human Development in Burma-Myanmar and the United States

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Embodied Foundations of the Self: Food, Grooming, and Cultural Pathways of Human Development in Burma-Myanmar and the United States A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology by Seinenu M. Thein 2013 © Copyright by Seinenu M. Thein 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Embodied Foundations of the Self: Food, Grooming, and Cultural Pathways of Human Development in Burma-Myanmar and the United States by Seinenu M. Thein Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Patricia M. Greenfield, Chair The present dissertation seeks to understand the origins of cultural differences in the self by examining two forms of embodied caregiving practices: eating and grooming. Although both eating and grooming lie at the intersection of culture, mind, biology, and social relationships, neither has been examined by psychologists as being possible mechanisms for cultural learning. Chapter 1 describes a mixed-methods (quantitative and qualitative) cross-cultural comparison of children’s eating practices in Burma-Myanmar and the United States. The study uses naturalistic video data of 55 children during routine family mealtimes to analyze non-verbal eating behaviors. Results indicate that there are significant cultural differences between families in Burma-Myanmar and the United States in embodied eating practices with regard to three variables: 1. Independence, 2. Agency, and 3. Social Intimacy. Children in the United States are more independent in their eating than children in Burma-Myanmar. Children in the United States are also more agentic, more frequently taking the initiative to eat; in Burma-Myanmar, the caregiver ii more often initiates eating. -

Flagging and Communications Manual

CLUB RACING SPECIALTY OPERATIONS MANUAL Flagging and Communications Sports Car Club of America, Inc. P.O. Box 19400 • 6700 SW Topeka Blvd., Building 300 Topeka, KS 66619 Phone 800.770.2055 • Fax 785.232.7214 F&C Manual 2012 – BOD Approved Table of Contents Forward and Credits i Introduction ii SECTION 1 Mission Statement 1 Purpose of Specialty 1 SECTION 2 General Information 2 The GCR 3 The F&C Team 3 The F&C Volunteer 4 Positions, Responsibilities, & Flags 5 Administration & Organization 5 Flags, Their Meanings & Use 6 SECTION 3 Specialty Volunteer Tasks 12 Station Operations 12 Communications 18 Emergency & Medical 23 Event Equipment 27 Station Equipment of all corners Personal Equipment SECTION 4 - APPENDIX A. Event Chain of Command 30 B. Flags Chart 32 C. Hand Signals 34 D. Hand Signals, Numbers 37 E. Attendance Sign In & Evaluation 39 Sample Sheets F. Communications Logging 46 Abbreviation Notes Report Forms Samples G. Witness Statement 51 F&C Manual 2012 – BOD Approved Forward and Credits With recognition that the Flagging and Communications community is an all volunteer force, it is important to understand the commitment and effort it takes to accomplish the major undertakings. The original SCCA F&C Manual was complied by and would not have been possible without the great efforts of many talented and dedicated F&C members. Each of those listed here deserve credit and mention for making it reality. Some of those contributors as listed in the Official 2002 Manual publication are as follows (in no specific order): Kathy Maleck, Bill -

IPMBA News Vol. 20 No. 4 Fall 2011

Conference 2012 ipmbaFall 2011 news Newsletter of the International Police Mountain Bike Association IPMBA: Promoting and Advocating Education and Organization for Public Safety Bicyclists. Vol. 20, No. 4 St. Paul’s Got it All Operation School’s Out by Maureen Becker by Kieran Sawyer, PCI #1192 Executive Director Milwaukee (WI) Police Department lans for the 22nd Annual IPMBA Conference are well underway. Members of the St. Paul Police Department and their hat could make for a better display of police partnering agencies are busy brainstorming ways to ensure this presence than a parade of 87 police officers on W bicycles rolling through neighborhoods? For two is a most memorable event. Myriad logistical arrangements will be undertaken to create an enjoyable, effective, and safe training days at the beginning of this summer, the Milwaukee Police environment. Department flooded our city streets and schoolyards with our entire bicycle unit. Our bike unit is comprised of 87 IPMBA The Minnesota Board of Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) trained officers, most of whom cycle for their tour of duty has looked favorably upon IPMBA, bestowing continuing education every day they work. credits (CECs) on four pre-conference courses and all conference Historically, the last workshops. A strategically planned schedule could yield up to 60 couple days of the hours between the pre-conference and the conference. Of course, the school year for CECs are only an ancillary reason to attend the event. The most Milwaukee Public important reason is the training itself. Schools are filled with For 22 years, the IPMBA conference has been recognized as the excitement, enthusiasm premier training event for public safety cyclists. -

Commercial Driver's Manual

..___.,, [U)[U)gj GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OFDRIVERSERVICES Let's Get Stan d... LOGIN CREATE AN ACCOUNT CO l E ASI\GIJEST) • R,ei nstate me nts ·Chang,eof Address •Motor Vehicle R,eport ·Custom Alerts •R,enewal ·Locations •R,eplacement ·Pay f,e,es •And More! GET IT ON Google Play COMMERCIAL DRIVERS MANUAL GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF DRIVER SERVICES DDS MISSION & CORE VALUES Our Mission CONTENTS To provide secure driver and identity credentials to our customers with excellence and respect. 4 Introduction Our Core Values: Driving Safely 16 • Trusted Service • Ethical Actions Transporting Cargo Safely 42 • Accountable to All Transporting Passengers Safely 44 • Motivated to Excellence Air Brakes 47 #ExcellenceIsWhatDRIVESUs! Title VI Policy Statement Combination Vehicles 53 The Georgia Department of Driver Services (DDS) is committed to compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and all related nondiscrimination au- Doubles and Triples 61 thorities. DDS assures that no person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, low-income, and Limited English Proficiency (LEP), be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise Tank Vehicles 64 subjected to discrimination under any program or activity. DDS further assures that every effort will be made to ensure nondiscrimination in all programs and Hazardous Materials 6 activities, whether or not those programs and activities are federally funded. 6 In addition, DDS will take reasonable steps to provide meaningful access to services for persons with Limited English Proficiency. Finally, DDS agrees to School Bus 78 abide by the Title VI Program Assurances and to ensure that written agree- ments with any party for federally funded programs or services will include the applicable Title VI language as provided in the Title VI Program Assurances. -

Anchorage Bike Rental I C S R Ia

Z e D G a A n o e B o m e o th 12 t nde rs n l t e i g r r t y el te t le l 1st Zuckert h e a g H n Fi W o s Good i w r i l n r n t y B k e e r e r i M e v et O l ed h o o io n arin r r s r o n P a s p c n n ctic W e t Ar o t n e e g o s e E t t V e a s e g a e S n l B b K k a i u W e r n e d l D l i l G a n c o r rd F o 2 r h i c c s C k n e e y v A s a t A B a r r a n lak e o n r d e P G Fr e G re Provider t er w n o g f s e R uf Richardso C B l n e w V 3rd g ie e i a rv l s t a i St g t Ward a r a Sharing the Trail e E w H d o ld oa rl a lr H a B rvard ai K Ha R isl O-street Biking i ng Glenn Highway Whitney k Trail e C ANCHORAGE re Viking Sm C e p n a Creek i k l Ship h Boundary t l e c S y Gold Kings n e B e o h Ship r P a nc n u ine r t a p a i Keep to the right. -

Death, Mourning and the Expression of Sorrow on White-Ground Lêkythoi

Portraits of Grief: Death, Mourning and the Expression of Sorrow on White-Ground Lêkythoi Molly Evangeline Allen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Molly Evangeline Allen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Portraits of Grief: Death, Mourning and the Expression of Sorrow on White-Ground Lêkythoi Molly Evangeline Allen In Athens in the early 5th century BCE, a new genre of funerary vase, the white-ground lêkythos, appeared and quickly grew to be the most popular grave gift for nearly a century. These particular vases, along with their relatively delicate style of painting, ushered in a new funerary scene par excellence, which highlighted the sorrow of the living and the merits of the deceased by focusing on personal moments of grief in the presence of a grave. Earlier Attic funerary imagery tended to focus on crowded prothesis scenes where mourners announced their grief and honored the dead through exaggerated, violent and frenzied gestures. The scenes on white-ground lêkythoi accomplished the same ends through new means, namely by focusing on individual mourners and the emotional ways that mourners privately nourished the deceased and their memory. Such scenes combine ritual activity (i.e. dedicating gifts, decorating the grave, pouring libations) with emotional expressions of sadness, which make them more vivid and relatable. The nuances in the characteristics of the mourners indicate a new interest in adding an individual touch to the expression, which might “speak” to a particular moment or variety of sadness that might relate to a potential consumer. -

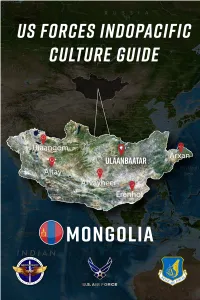

CG Mongolia 2020.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: Mongolian dancers perform the East Mongolian dance during Mongolian culture night for Khaan Quest). Mongolia The guide consists of two parts: Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on East Asia. C Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Mongolian society. It applies culture-general concepts to help ul increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment t location. This section is meant to complement other pre- u deployment training. (Photo: Mongolians perform a folk dance called “Aduuchin,” which re means “horseman” and celebrates the importance of Guid horses to nomadic Mongolians). For more information, visit the Air Force Culture and e Language Center (AFCLC) website at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments.