Music to My Ears

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Book Review: Dirty Little Secrets

10 THURSD A Y , OCT O B E R 21, 2010 ARTS A ND ENT E RT A INM E NT VA L E NCI A HIGH SCH oo L THE BAND WI ll IN-HERI T AGE T HE EAR T H The band is going to go out and repre- DJ, entertainers, and several specialty such delectable treats, there’s more By: Allen Lin sent our school.” Starting at 9:30 from areas. There will be mimes, clowns, than enough to satisfy. Perhaps you’ll Reporter Morse Avenue, the parade will go north jugglers, slot car racing, and giant follow Mr. Perez’s example and “take on Kraemer until it reaches Tri-city inflatable activities. One could truly a sample of pretty much everything.” Prosperity is a hard thing to de- Park. The parade isn’t the only reason say there are games galore. Clowns Or perhaps one might find a car show fine, but this year we’re on the more appealing, and there’s plenty to road to it, for Placentia’s 46th look at in the festival’s. With over 200 Heritage Festival and Parade! cars, it will automo-blow your mind. March with the band to Tri-City Park There will also be a Business Expo for this October; they’re heading to the emergent entrepreneurs. The Craft Fair Heritage Festival Parade! With over showcases items made with care, with 200 entries participating in the parade, over 40 shops stocked with handmade it’s sure to be one of the most stun- products. Non-profit area will have a ning sights of the year! El Tigre had a variety of organizations explaining chance to meet and discuss the parade how they are improving Placentia. -

Meet Nasty Habit Cherry Bomb Review Mental Illness In

MEET NASTY HABIT CHERRY BOMB REVIEW MENTAL ILLNESS IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY 20 WATTS | 1 01 // THE CITY - THE 1975 02 // YESTERDAY - ATMOSPHERE 03 // GRINDIN’ - CLIPSE 04 // AFRICA - TOTO 05 // GRAVITY - TURNSTILE 06 // CLUSH - ISLES & GLACIERS 07 // R U MINE? - ARCTIC MONKEYS 08 // CLARK GABLE - POSTAL SERVICE 09 // CAROLINA - SEU JORGE 10 // NO ROOM IN FRAME - DEATH CAB FOR CUTIE 11 // JESUS TAKE THE WHEEL - CARRIE UNDERWOOD 12 // A WALK - TYCHO 13 // SEDATED - HOZIER 14 // HEY YA! - OUTKAST 15 // MY BODY - YOUNG THE GIANT 16 // DREAMS - FLEETWOOD MAC 17 // PAST LIVES - BØRNS 18 // PLEASE DON’T - LEO STANARD TWEET @20_WATTS WHAT 19 // TOTALLY FUCKED - JONATHAN GROFF YOU’RE LISTENING TO! 20 // TUBTHUMPING - CHUMBAWAMBA Cover Photo by Adam Gendler 2 | 20 WATTS 20 WATTS | 3 20 WAT TSSPRING 2015 WE ASKED: WHAT IS YOUR EMOJI STORY? LYNDSEY JIMENEZ RIKKI SCHNEIDERMAN ADAM GENDLER JANE DEPGEN PHIL DECICCA EDITOR IN CHIEF MANAGING EDITOR MULTIMEDIA CREATIVE DIRECTOR HEAD DESIGNER MIKEY LIGHT SAM HENKEN JACKIE FRERE TIFFANY GOMEZ JOEY COSCO JAKE LIBASSI FEATURES EDITOR ASSISTANT FEATURES FRONT OF BOOK PHOTO EDITOR DIGITAL DIRECTOR WEB EDITOR A SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR CONTRIBUTORS: KAITLIN GRENIER COLE HOCK TOMMY ENDE KENNY ENDE ERIN SINGLETON CAROLYN SAXTON KATIE CANETE JIM COLEMAN WILL SKALMOSKI COPY EDITOR REVIEWS + PUBLICIST PUBLISHER MARKETING SOCIAL MEDIA 4 | 20 WATTS 20 WATTS | 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS 08 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 10 THE FIVE 11 EAR TO THE GROUND 12 ON THE GRIND 13 PLAYLIST // 20 WATTS GOES ABROAD 15 BACK FROM THE DEAD 16 DROP THE MIC // SEXUALITY IN MUSIC 18 A DAY IN THE LIFE W/ NASTY HABIT 22 WHAT IS EDM? 24 2015: THE YEAR OF HIP-HOP 26 REVIEW // CHERRY BOMB 28 Q&A // RICKY SMITH 31 HEADSPACE 34 DIY, YOU WON’T 38 FUSION FRENZY 42 BACK OF BOOK LETTER 6 | 20 WATTS 20 WATTS | 7 There’s a lot that goes into making a magazine — a lot of arguments, a lot of cuts, a whole lotta shit that you probably don’t even think about as you’re holding this book in your hands right now. -

Grammy-Nominated Florence + the Machine Provide Soundtrack for Fifa Women’S World Cup 2015™ on Fox

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, June 3, 2015 GRAMMY-NOMINATED FLORENCE + THE MACHINE PROVIDE SOUNDTRACK FOR FIFA WOMEN’S WORLD CUP 2015™ ON FOX Music from Grammy Award-nominated English rock band Florence + The Machine provides the backdrop for FOX Sports’ coverage of FIFA Women’s World Cup 2015™ when the tournament begins later this week. FOX Sports has gained the rights to all 11 songs featured on Florence + The Machine’s new album, “How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful,” along with nine additional cuts from her catalog, including hit songs “Shake It Out” and “Dog Days Are Over.” The title track from “How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful” is used to close coverage most nights, while other songs score coverage elsewhere, a few providing the musical backdrop to some of the more than 60 team and player features produced specifically for FOX Sports’ FIFA Women’s World Cup 2015 coverage. The track “Mother” plays in a story about U.S. Women’s National Team player Christie Rampone – a mother of two who turns 40 during the World Cup, and “Third Eye” accompanies a feature on the artistic USWNT midfielder Megan Rapinoe, a guitarist, style aficionado and openly gay. The complete list of tracks follows: How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Ship to Wreck What Kind of Man How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Queen of Peace Various Storms and Saints Delilah Long and Lost Caught Third Eye St. Jude Mother Catalog Shake It Out Dog Days Are Over Rabbit Heart (Raise It Up) Drumming Song No Light, No Light Spectrum Howl Breaking Down Cosmic Love - more - FLORENCE & THE MACHINE—Page 2 FOX Sports is set to execute the most expansive multi-platform coverage ever of the FIFA Women’s World Cup™, including an unprecedented 16 matches airing live on FOX broadcast network. -

Women's Track and Field Takes First Place, Men

The Bates Student THE VOICE OF BATES COLLEGE SINCE 1873 WEDNESDAY January 22, 2014 Vol. 143, Issue. 11 Lewiston, Maine FORUM ARTS & LEISURE SPORTS Kristen Doerer ’14 explains Ashley Bryant ’16 recaps the Track has strong showing at Bates the necessity of remembering much anticipated MLK Sankofa Invitational while men’s squash domi- lesser known leaders of the civil perfomance entitled “H.O.M.E.” nated Mount Holyoke round robin. rights movement. See Page 4 See Page 7 See Page 12 J Street U Emily Bamford’s pursuit of the Olympic dream reacts to ASA boycott JULIA MONGEAU ASSISTANT NEWS EDITOR Bates has recently added the col- lege’s voice to a educational conflict in Israel. President Clayton Spencer re- cently joined many other colleges and universities in rejecting the American Studies Associations boycott of Israeli academic institutions. In her official statement released January 10th, Spen- cer articulates, “Academic boycotts strike at the heart of academic freedom and threaten the principles of dialogue, scholarly interchange, and open debate that are the lifeblood of the academy and civil society.” Many argue that the prevention of the exchange of ideas and the hindrance of academic freedom are major reasons to disagree with the boycott. Those in support of the boycott suggest that it is necessary action in order to make sig- nificant strides towards a resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. None the less, a relatively unknown organiza- tion has recently become infamous and caused a widespread reaction and a divi- sion of opinions in the academic world. In a note from ASA National Coun- cil on the ASA website, the council com- mented “The resolution is in solidarity with scholars and students deprived of their academic freedom and it aspires to Bamford ‘15 poses during a team photo shoot. -

Student Comments About Single Gender Social Organizations

2016 Harvard College Prepared by HCIR STUDENT COMMENTS ABOUT SINGLE GENDER SOCIAL ORGANIZATIONS Survey Comments from AY 2010-2011 through AY 2014-15 Survey Comments about Single Gender Social Organizations Please use the space below to elaborate on any of the questions on the survey and to comment on any other aspect of your undergraduate experience not covered in this questionnaire Socially, Harvard needs to address some social issues that they seem to neglect. I am deeply concerned about the house renovation projects, which, to my understanding, are essentially getting rid of private common rooms (replacing with "public" common rooms). In doing so, the university is naively and unrealistically not giving students ways to engage in social behaviors that college students will undeniably do. This also increases the demand and power of final clubs and other organizations that have great social spaces (pudding institute, lampoon, crimson, etc), which will exacerbate many of the negative social pressures that exist on campus (dynamics between final club students and others, gender-related issues - especially sexual assault, etc). The point is, Harvard needs to be mature about and accept the fact that college students engage in various social behaviors and thus do things to help students do these things in a safer and more accessible way. Pretending like they don't exist simply makes the situation worse and students have a much worse experience as a result. 2013-2014 Senior Male 1) I think there is a strong need for more final club/fraternity-type opportunities for undergraduate students. This experience is currently restricted to only a small percentage of the male student body, and could offer tremendous opportunities for growth. -

AUSTIN CITY LIMITS DOUBLE-BILL: FLORENCE + the MACHINE & ANDRA DAY New Episode Premieres October 22 On

AUSTIN CITY LIMITS DOUBLE-BILL: FLORENCE + THE MACHINE & ANDRA DAY New Episode Premieres October 22 on PBS Austin, TX—October 20, 2016—Austin City Limits (ACL) presents a breathtaking hour with two of today’s most inspirational acts: Florence + the Machine in their return appearance and Andra Day in a standout ACL debut. The new installment airs October 22nd at 8pm CT/9pm ET as part of ACL’s new Season 42. The program airs weekly on PBS stations nationwide (check local listings for times) and full episodes are made available online for a limited time at pbs.org/austincitylimits immediately following the initial broadcast. Viewers can visit acltv.com for news regarding future tapings, episode schedules and select live stream updates. The show's official hashtag is #acltv. It’s been over five years since UK hitmakers Florence + the Machine first-appeared on the ACL stage. Now international superstars and one of rock’s biggest live acts, the unstoppable band make a triumphant return with a high-energy, buoyant five-song set. Dynamic leader Florence Welch dances barefoot across the stage performing songs from their recent, chart-topping LP How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful. Her knockout vocals and remarkable rapport with fans captivate throughout as she enlists the crowd as a “hungover choir of angels” for the Grammy- nominated “Shake It Out” from 2011’s Ceremonials, closing with a rapturous performance of the band’s 2009 breakthrough smash, the anthemic “Dog Days Are Over.” "Florence brings a unique performance art to all of her shows, and she took it to a new level this night,” says ACL executive producer Terry Lickona. -

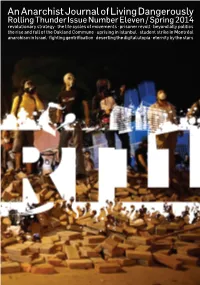

An Anarchist Journal of Living Dangerously Rolling Thunder Issue Number Eleven / Spring 2014 Revolutionary Strategy

An Anarchist Journal of Living Dangerously Rolling Thunder Issue Number Eleven / Spring 2014 revolutionary strategy . the life cycles of movements . prisoner revolt . beyond ally politics the rise and fall of the Oakland Commune . uprising in Istanbul . student strike in Montréal anarchism in Israel . fighting gentrification . deserting the digital utopia . eternity by the stars In Seattle, we wrote the legal number on our arms in marker To call a lawyer if we were arrested. In Istanbul, people wrote their blood types on their arms. I hear in Egypt, They just write their names. Table of Contents “You must have chaos within you to give birth to a dancing star.” – Friedrich Nietzsche Kicking It Off 2 Introduction: This One Goes to 11 4 Glossary of Terms, Featuring Victor Hugo and Charles Baudelaire Letters from the Other Side 8 Days of Teargas, Blood, and Vomit— A Dispatch from Prisoner Sean Swain After the Crest: The Life Cycles of Movements 13 What to Do when the Dust Is Settling 19 The Rise and Fall of the Oakland Commune 34 Montréal: Peaks and Precipices— Student Strike and Social Revolt in Québec Eyewitness Report 52 Addicted to Tear Gas: The Gezi Resistance, June 2013 Critique 69 Ain’t No PC Gonna Fix It, Baby: A Critique of Ally Politics Investigation 78 How Do We Fight Gentrification? Analysis 98 Deserting the Digital Utopia: Computers against Computing Interviews 104 Israeli Anarchism: A Recent History Reviews 121 EtErnity by thE StarS, Louis-Auguste Blanqui 125 Interview with Frank Chouraqui, translator of EtErnity by thE StarS The End 128 Prognosis Going all the way means defending parks and neighborhoods, bankrupting developers, bringing capitalism to a halt with a general strike. -

Regional Oral History Office University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Judith Smith Artistic Director, AXIS Dance Company Interviews conducted by Esther Ehrlich in 2005 Copyright © 2006 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Judith Smith, dated January 14, 2005. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

How Big How Blue How Beautiful Album Download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Download

how big how blue how beautiful album download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Download. 1. Ship to Wreck 2. What Kind of Man 3. How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful 4. Queen Of Peace 5. Various Storms & Saints 6. Delilah 7. Long & Lost 8. Caught 9. Third Eye 10. St Jude’ 11. Mother 12. Hiding 13. Make Up Your Mind 14. Which Witch 15. Third Eye (Demo) 16. How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful (Demo) 17. As Far As I Could Get. Tags: Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Leak Download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Leak Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful zip download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful album mp3 download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album 320 kbps Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Leaked Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful has it leaked Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful (2015) Album Leak Download. Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Download. 1. Ship to Wreck 2. What Kind of Man 3. How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful 4. Queen Of Peace 5. Various Storms & Saints 6. Delilah 7. Long & Lost 8. Caught 9. Third Eye 10. St Jude’ 11. Mother 12. Hiding 13. Make Up Your Mind 14. Which Witch 15. Third Eye (Demo) 16. How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful (Demo) 17. -

Gigs of My Steaming-Hot Member of Loving His Music, Mention in Your Letter

CATFISH & THE BOTTLEMEN Van McCann: “i’ve written 14 MARCH14 2015 20 new songs” “i’m just about BJORK BACK FROM clinging on to THE BRINK the wreckage” ENTER SHIKARI “ukiP are tAKING Pete US BACKWARDs” LAURA Doherty MARLING THE VERDICT ON HER NEW ALBUM OUT OF REHAB, INTO THE FUTURE ►THE ONLY INTERVIEW CLIVE BARKER CLIVE + Palma Violets Jungle Florence + The Machine Joe Strummer The Jesus And Mary Chain “It takes a man with real heart make to beauty out of the stuff that makes us weep” BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME15011142.pgs 09.03.2015 11:27 EmagineTablet Page HAMILTON POOL Home to spring-fed pools and lush green spaces, the Live Music Capital of the World® can give your next performance a truly spectacular setting. Book now at ba.com or through the British Airways app. The British Airways app is free to download for iPhone, Android and Windows phones. Live. Music. AustinTexas.org BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME15010146.pgs 27.02.2015 14:37 BAND LIST NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 14 MARCH 2015 Action Bronson 6 Kid Kapichi 25 Alabama Shakes 13 Laura Marling 42 The Amorphous Left & Right 23 REGULARS Androgynous 43 The Libertines 12 FEATURES Antony And The Lieutenant 44 Johnsons 12 Lightning Bolt 44 4 SOUNDING OFF Arcade Fire 13 Loaded 24 Bad Guys 23 Lonelady 45 6 ON REPEAT 26 Peter Doherty Bully 23 M83 6 Barli 23 The Maccabees 52 19 ANATOMY From his Thai rehab centre, Bilo talks Baxter Dury 15 Maid Of Ace 24 to Libs biographer Anthony Thornton Beach Baby 23 Major Lazer 6 OF AN ALBUM about Amy Winehouse, sobriety and Björk 36 Modest Mouse 45 Elastica