National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nov 27: Check-In to Memphis Sheraton Downtown. Beale Street

Cruise the Mississippi River like the King (or Queen)! This Memphis to New Orleans 10-night package will open up the world of Elvis, the King of Rock and Roll, with the Platinum Ticket to Graceland, as well as the music of Beale Street in Memphis. Then you’ll be rolling down the river onboard the American Queen for 7-nights before finishing your vacation with two nights in New Orleans – and there’s no place in the world like New Orleans! This unique package is a USA River Cruise exclusive package – call today to reserve your space! 800-578-1479 | 360-546-5151 | [email protected] CRUISE ITINERARY: NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 7, 2016 Nov 27: Check-in to Memphis Sheraton Downtown. Beale Street and Peabody Hotel Tours. Nov 28: Board the American Queen. Guided tour of Memphis and Platinum Ticket to Graceland for self-guided tour included. Nov 29: Greenville, MS Nov 30: Vicksburg, MS Dec 1: Natchez, MS Dec 2: St. Francisville, LA Dec 3: Baton Rouge, LA Dec 4: Nottoway, LA Dec 5: Disembark in New Orleans, LA. Premium Shore excursion included. 2-night hotel stay included. Dec 6: New Orleans Bayou and Swamp Tour. Dec 7: Transfers to the airport included. Onboard the American Queen: Authentic overnight paddlewheel steamboat Gracious, friendly service from a professionally trained all-American staff Ambiance of an antebellum mansion 24-Hour Room Service All onboard meals included, fine dining and casual Complimentary wine and beer with dinner Complimentary cappuccino, espresso, specialty coffees, tea, bottled water and soft drinks Complimentary Hop-On/Hop-Off -

KM Tours Memphis Music City

KM Tours Presents Memphis Music City August 17 – 21, 2016 $985 Per Person, Double Occupancy from Hartford Tour Highlights Complete sightseeing schedule Visit to the Top of the St. Louis Arch! Sightseeing Tour of Memphis See the Peabody Duck March! Visit historic Beale Street Mississippi River Diner Cruise Visit and tour of Elvis’ Graceland Visit historic Sun Studios 8 Meals four dinners and four breakfasts Deluxe motor coach transportation from Hartford Plus much more! Day by Day Itinerary Wed., Aug. 17 – HARTFORD/ST LOUIS Sat., Aug. 20 – MEMPHIS This morning we depart Hartford and the Milwaukee This morning we walk in the footsteps of the King of area on our exciting journey to Memphis “Music City.” Rock 'n' Roll at Elvis' home, Graceland. Our tour will We'll travel south through Illinois and across the take us from Elvis' humble beginnings through his rise mighty Mississippi River to St. Louis, “The Gateway to superstardom. See how a rock 'n' roll legend lived to the West”. This evening we enjoy dinner in St. and relaxed with family and friends. We begin with an Louis. (D) audio tour through the Mansion including the famous Jungle Room, and see Elvis' gravesite in the Meditation Thurs., Aug. 18 – ST. LOUIS/MEMPHIS Garden. Stroll through the Auto Museum to see more Today we begin with a visit to the famous St. Louis than 30 unique vehicles owned by Elvis, enjoy the Elvis Arch. We will ride the tram up to the top for a wonder- Archives Experience, and grab Elvis' favorite peanut ful view over the city and Mississippi River. -

Memphis Architectural Collection

MEMPHIS ARCHITECTURAL COLLECTION Processed By: Regan Adolph & Lanier Flanders 2013 Memphis and Shelby County Room Memphis Public Library and Information Center 3030 Poplar Avenue Memphis, TN 38111 Memphis Architectural Collection Historical Sketch The Memphis Architectural Collection is a diverse compilation of architectural designs that were constructed in Memphis and Shelby County throughout the 20th century. Various classifications of buildings including businesses, residences, hospitals, hotels, theaters, social clubs, and buildings that provide public services are featured. This collection represents the rich heritage of Memphis as it evolves from a trading port on a bluff of the Mississippi into a vibrant metropolitan city of the 21st century. Starting in 1900, Memphis began to flourish as a city. Attractions such as Overton Park and the Memphis Zoo emerged. In 1904, the Parkways were constructed in a quad-like pattern to surround Overton Park. Talented designers and architects found themselves working in Memphis; some of the earliest firms featured in this collection include Hanker & Cairns, Walter W. Ahlscharlger, Jones & Furbringer, and James B. Cook. Ornate, luxurious hotels such as the Peabody Hotel, the Gayoso Hotel, the Chisca Hotel, and the Chickasaw Hotel are all results of this grandiose era. Various businesses, such as Memphis Steam Laundry, Lowenstein’s Department Store, the E.H. Crump building, the Memphis Royal Crown Bottling Co., and the Pantaze Drugstore all reflect the industry, investment, and enterprise of downtown Memphis. This collection contains nearly 60 designs from the Hanker & Cairns architectural firm. After studying in Paris, Bayard Snowden Cairns arrived in Memphis in 1904 at the request of his cousin R. -

MEMPHIS the 2016 William F

THINGS TO DO IN MEMPHIS The 2016 William F. Slagle Dental Meeting will be held for the 21st Sun Studio consecutive year in our home city of Memphis, Tennessee. The University of Tennessee College of Dentistry and Dental Alumni Do you recognize these names? Association welcome you. We hope you will take advantage of the Jerry Lee Lewis, B.B. King, Carl wide variety of attractions Memphis has to offer, such as art galleries, Perkins and Elvis Presley? These antique shops, fine restaurants, historic sites, and of course, the men began their recording careers music. Memphis is known for the blues, but you will find music at Sun Studio, founded in 1950 by for all tastes. Here is a quick reference guide to use during your Sam Phillips. It is still functioning stay. For more detailed information, call the Memphis Convention as a studio and many modern Bureau at (901) 543-5300 or log on to www.memphistravel.com or artists take their turns recording www.gomemphis.com. here hoping to catch a little magic. Tours are offered during the day every hour on the half hour. Of special interest is a gallery Graceland that contains records, photographs, memorabilia and autographs The antebellum-style house that Elvis Presley bought in 1957 is a of Sun recording legends. major tourist attraction. Tours depart from the complex on Elvis 706 Union, 901-521-0664 Presley Boulevard every fifteen minutes. Visitors can walk the www.sunstudio.com grounds, tour the house, which includes the dining room where Elvis often took a late evening meal with ten or twelve friends, and which boasts a custom chandelier made in Memphis. -

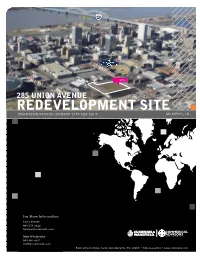

Redevelopment Site Downtown Redevelopment Site for Sale Memphis, Tn

a WEST UNION AVE BEALE ST SITE 285 UNION AVENUE REDEVELOPMENT SITE DOWNTOWN REDEVELOPMENT SITE FOR SALE MEMPHIS, TN For More Information: Larry Jensen 901.273.2344 [email protected] Matt Weathersby 901.362.4317 [email protected] 5101 Wheelis Drive, Suite 300, Memphis, TN 38117 • 901-366-6070 • www.commadv.com UNION AVE THE PROPERTY Overview The CCL Label Site is 3.37 acres and is located at 285 Union Avenue in downtown Memphis, Tennessee. This facility is located in the heart of the Sports and Entertainment district and has emerged as a strategic site that can be utilized as a much needed link between AutoZone Park, FedEx Forum, and Beale Street and may also serve as a Gateway entrance into downtown from the East. Details • Sports & Entertainment District • Located between Autozone Park and the FedEx Forum • Acreage - 3.37 • Union Avenue Frontage • Zoning - CBD Redevelopment Potential This site’s unique location in the heart of the sports and entertainment district of downtown Memphis provides an outstanding opportunity for a one-of-a-kind mixed-use development. It is conveniently located near Fourth and Union adjacent to Autozone Park and one block from Beale Street, which is the #1 tourist attraction in Tennessee OVERVIEW drawing more than five million visitors annually. This site is perfectly situated between Memphis’ two major sports facilities: Autozone Park (home of the Memphis Redbirds, the AAA affiliate of the St. Louis Cardinals attracting 700,000 visitors annually) and the FedEx Forum (Memphis’ largest public arena, seating up to 18,165 and home to Memphis Grizzlies and the University of Memphis Tigers). -

Robert Lanier Collection Processed by Victoria Grey 2014 Memphis And

Robert Lanier Collection Processed by Victoria Grey 2014 Memphis and Shelby County Room Memphis Public Library and Information Center 3030 Poplar Avenue Memphis, TN 38111 Biographical Note Robert Lanier was born in Memphis in 1938, and has spent most of his life in the city. His contributions to the Memphis law community began after he completed his Bachelor of Science from Memphis State University (now U of M) and his Bachelor of Laws from the University of Mississippi, in 1960 and 1962 respectively. Lanier received the American Spirit of Honor Medal in 1963. He was a member of the Memphis law firm of Armstrong, McAdden, Allen, Braden and Goodman from 1964-1968, as well as Farris, Hancock, Gilman, Branan, Lanier & Hellen in 1968. After his stints at these two practices, he became the director of the Memphis & Shelby County Junior Bar Association in 1969-1970, as well as secretary of that same organization in 1971. During this time, he was appointed as special judge at both Circuit and General Sessions Courts, and the Memphis City Court. He served as a judge from 1969 until his retirement in 2004. Lanier also served as an Adjunct Professor at the Memphis State University School of Law (U of M) from 1981, and was a member of the Shelby County Republican Executive Committee, from 1970-1972. He was involved in both the Memphis and Tennessee Humane Associations. Starting out as director of the former in 1972, he eventually became president of both, in Memphis in 1974 and as the state’s from 1975-1977. -

Vehicle Repair Shop Isn't Budging from Jackson Ave. Home

Public Records & Notices Monitoring local real estate since 1968 View a complete day’s public records Subscribe Presented by and notices today for our at memphisdailynews.com. free report www.chandlerreports.com Tuesday, May 25, 2021 MemphisDailyNews.com Vol. 136 | No. 62 Rack–50¢/Delivery–39¢ Collierville, Bartlett students take top honors in airport art contest ABIGAIL WARREN May 19. Students from schools Meredith Dai, a Collierville painting.” Her artwork depicted the Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Courtesy of The Daily Memphian across Shelby County showed off High sophomore, took home first a live concert at Levitt Shell in said during the event. “It was Winners for Memphis Interna- their interpretations of Memphis place for her painting titled “A Overton Park, but highlighted a original. The skill was so strong, tional Airport’s 14th annual High culture. Levitt Picnic.” family enjoying a picnic as many and it felt like I was sitting on the School Visual Arts and Photogra- While 51 pieces will hang in “I love music and I love food enjoy the show. picnic blanket with this family at phy Competition were announced the airport for a year, six received and the community and the cul- “I fell out when I saw that the show.” during a virtual program hosted special recognition and the artists ture of Memphis as a whole,” she piece,” judge Karen Strachan, by cityCURRENT on Wednesday, awarded cash prizes. said. “I tried to fit it all in one youth program coordinator of ART CONTINUED ON P2 commercial artery that runs through or near the economically distressed neighborhoods of Nutbush, Vehicle repair shop isn’t budging Douglass and the Heights. -

Gjlljjs. Credly Conndentlal

THE MEMPHIS DAILY APPEAL THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 1870. SEPTENNIAL INSTITUTE 19c; Middlings, 20c; Good FINANCE AND TRADE. come reduced in those countries where Middlings, EDUCATIONAL It baa bean sustained by "war do., 21Xc; Mobile, 20KC; Orleans, aic. LEVER POWER prices," and be continued and in- 11 :30 a.m. Cotton dull and lower, ask THE UTLEY IMPROVED h.xjieii-.il.- September 17?ic. October xn. ' creased where most favored by natural lna for ltc. MISS J. McKAIN Daily 1 advantages. such a the November 16Kc Ordinary, 14o; Good Or MARY SEPTENNIAL Office of Amu, In competition, - Memphis, Septembertii 7, 1870. J United States, having everything in its dinary 164c; Middlings UMtc; ijp- TAEPiRfiB to announce to her Datrona and Monne, zu.v,c; to the public generally, that she has IMPORTANT FBOM IlCTSaXaX RBVKKCS favor, must outstrip all competitors and lands, isw: oood do., zi U hold a practical monopoly, aa of old. Orleans, 200. formed a coalition with Mrs. Emma Carioll MEDICAL ir.STITUTfc, adapted Tucker. This school will be taught at the muii brokers, With a soil and climate exactly New Yoax, September 7, 2:05 p.m. brick building. No. lis Court stieet, where The wholesale dealers, oattle to cotton growing, improved meth- ( otton o on soot. every arrangement for BDOthacaries. special taxes, lm with met nut steadv. sales has been made ths and other ods of with vast plantations di- 1000 balee. 2000 bales; Sep or ineir pupils, tney win oe assisted 42 North Court St., Memphis, TV, aot 30, culture, Contracts. roDion - posed under section of Jane vided into farms, and an adequate supply tember, 17K; October, 16K16)i; De- by Professor Tpe and Mrs. -

Delta: Everything Southern, 2012, Brochure

University of Memphis University of Memphis Digital Commons Video Delta: Everything Southern, 2012 8-5-2021 Delta: Everything Southern, 2012, brochure Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/speccoll-exhibit- ev_south2012-av1 Dear Friends of the Delta, A Day of Distinguished Speakers, 8:15 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. a.m. – 4:30 8:15 Friday, June 8, 2012 June 8, 2012 Friday, Welcome to the seventh annual The Delta–Everything Images and Music Southern! conference. We are so thankful for your support, encouragement and participation in the years since we began this beloved day of celebration of what we all know to be the most interesting and important region of our country. The University of Memphis, one of 46 Tennessee Board of Regents Institutions, is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action University. UOM323-FY1112/5M Board of Regents Institutions, is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action University. University of Memphis, one 46 Tennessee The This year brings excellent new presenters, great music, and a new approach to our afternoon sessions. We hope you’ll join us for what has become everyone’s “favorite day of the year.” Bring a friend, see old friends and new, and help us make the 2012 conference the best ever. I look forward to seeing each and every one of you on June 8, 2012. WALK IN THE LIGHT, courtesy Dolph Smith Sincerely, Willy Bearden, Chairman, The Delta–Everything Southern! Thank You To Our Sponsors and Friends! Mr. and Mrs. John Shepherd Methodist LeBonheur Healthcare Inc. Memphis Magazine Pride of the Pond Catfish Community Foundation of Greater Memphis Dr. -

2019 Education Curriculum Guide

Tennessee Academic Standards 2019 EDUCATION CURRICULUM GUIDE MEMPHIS IN MAY INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL Celebrates Memphis in 2019 For the fi rst time in its 43-year history, Memphis in May breaks with tradition to make the City of Memphis and Shelby County the year-long focus of its annual salute. Rather than another country, the 2019 Memphis in May Festival honors Memphis and Shelby County as both celebrate their bicentennials and the start of a new century for the city and county. Memphis has changed the world and will continue to change the world. We are a city of doers, dreamers, and believers. We create, we invent, we experiment; and this year, we invite the world to experience our beautiful home on the banks of the Mississippi River. The Bluff City…Home of the Blues, Soul, and Rock & Roll…a city where “Grit and Grind” are more than our team’s slogan, they’re who we are: determined, passionate, authentic, soulful, unstoppable. With more than a million residents in its metro area, the City of Memphis is a city of authenticity and diversity where everyone is welcomed. While some come because of its reputation as a world-renown incubator of talent grown from its rich musical legacy, Memphis draws many to its leading hospital and research systems, putting Memphis at the leading edge of medical and bioscience innovation. Situated nearly in the middle of the United States at the crossroads of major interstates, rail lines, the world’s second-busiest cargo airport, and the fourth-largest inland port on the Mississippi River, Memphis moves global commerce as the leader in transportation and logistics. -

Memphis Police Department Homicide Reports 1917-1936

Memphis Police Department Homicide Reports 1917-1936 Processed by Cameron Sandlin, Lily Flores, and Max Farley 2017 Memphis and Shelby County Room Memphis Public Library and Information Center 3030 Poplar Ave Memphis, TN 38111 Memphis Police Department Homicide Reports 1917-1936 2 Memphis Police Department Homicide Reports 1917-1936 Memphis Police Department Historical Sketch The history of police activity in Memphis began in 1827 with the election of John J. Balch. Holding the title of town constable, the “one-man Police Department” also worked as a tinker and patrolled on foot an area of less than a half square mile in the young town of Memphis.1 As the river town expanded and developed a rough reputation throughout the 1830’s, the department remained small, first experiencing growth in 1840 when the force expanded to include the Night Guard, a night-shift force of watchmen. In 1848, the town of Memphis became the city of Memphis. During that same year, the elected office of City Marshal replaced the position of town constable, and the duties of the office expanded to include “duties related to sanitation, zoning, street maintenance,” in addition to policing the newly-minted city.2 In 1850, the total police force numbered 26 men, split between the Day Squad and the Night Squad, and by 1860, a police force with a structure that could be characterized as modern was in place in Memphis, with the position of Chief of Police clearly stated in city ordinances as the leader of the police force. Following the Civil War, the Memphis Police Department (MPD) expanded to manage the rapidly growing Bluff City. -

New Huntington Herald

Published Exclusively for former crewmen of USS HUNTINGTON CL-107 Huntington Herald Volume 23, Issue 3 September 2013 Inside this issue: Recap of the 2013 1-2 reunion Attendees List 3 Taps 3 2013 USS HUNTINGTON REUNION RECAP Gene Volcik’s 3 The first joint reunion This was the spot to re- ship and something about Message of the USS Mississippi new old friendships and their personal life. This (EAG-128) and the USS make new ones with for- was a good ice-breaker, Mail Call 3 Huntington (CL-107) was mer sailors and guests because before you knew held in Washington, DC from the other ship. The it, everyone was swap- Preview of Memphis 4-6 from Thursday, Septem- two groups melded al- ping stories about life on ber 5 through Monday, most immediately and this board either the Missis- September 9, 2013. The made for a very pleasant sippi or the Huntington. IMPORTANT Crowne Plaza Crystal City reunion atmosphere. The The remainder of the eve- NOTE Hotel served as the host first official item on the ning was free to enjoy facility for the reunion. reunion agenda was the Washington or to relax in Seven crewmen and Welcome Reception held the hospitality room. seven guests attended at 5:00 PM. Paul She- Friday morning after from the USS Mississippi pley, coordinator of the breakfast in the hotel, and four crewmen and USS Mississippi, wel- everyone was eager to three guests attended comed both groups to the get going on the Big Bus! from the USS Huntington reunion. Gene Volcik, Everyone gathered in the for a grand total of twenty- USS Huntington coordina- hotel lobby and were one attendees.