Binisaya, a New Generation of Cebuano Filmmakers: an Interview with Keith Deligero and Ara Chawdhury Patrick F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workplaces with the Rockwell Mother's May

MAY 2016 www.lopezlink.ph http://www.facebook.com/lopezlinkonline www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph Registration is ongoing! See details on page 10. #Halalan2016: All for the Filipino familyBy Carla Paras-Sison ABS-CBN Corporation launches its election coverage campaign about a year before election day. But it’s not protocol. Ging Reyes, head of ABS-CBN Integrated News and Current Affairs (INCA), says it actually takes the team a year to prepare for the elections. Turn to page 6 Workplaces with Mornings Mother’s the Rockwell with the May touch…page 2 ‘momshies’…page 4 …page 12 Lopezlink May 2016 Lopezlink May 2016 Biz News Biz News 2015 AUDITED FINANCIAL RESULTS Period Dispatch from Japan Total revenues Net income attributable to equity January- holders of the parent Building Mindanao’s September Workplaces with Design-driven PH products showcased in 2014 2015 % change 2014 2015 % change By John ALFS fest Porter ABS-CBN P33.544B P38.278B +14 P2.387B P2.932B +23 largest solar farm Lopez Holdings P99.191B P96.510B -3 P3.760B P6.191B +65 theBy Rachel Varilla Rockwell touch KIRAHON Solar Energy cure ERC [Energy Regulatory ing to the project’s success,” said EDC P30.867B P34.360B +11 P11.681B P7.642B -34 Corporation (KSEC) has for- Commission] approval and the KSEC CEO Mike Lichtenfeld. First Gen $1.903B $1,836B -4 $193.2M $167.3M -13 DELIVERING the same me- As the first mally inaugurated its 12.5- first to secure local nonrecourse Kirahon Solar Farm is First FPH P99.307B P96.643 -3 P5.632B P5.406B -4 ticulous standards it dedicated prime of- megawatt Kirahon Solar Farm debt financing, it was important Balfour’s second solar power ROCK P8.853B P8.922B +1 P1.563B P1.644B +5 to its residential developments, fice project of in Misamis Oriental. -

COVER SHEET for AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A

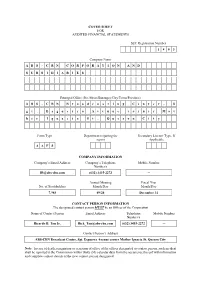

COVER SHEET FOR AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A B S - C B N C O R P O R A T I O N A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S Principal Office (No./Street/Barangay/City/Town/Province) A B S - C B N B r o a d c a s t i n g C e n t e r , S g t . E s g u e r r a A v e n u e c o r n e r M o t h e r I g n a c i a S t . Q u e z o n C i t y Form Type Department requiring the Secondary License Type, If report Applicable A A F S COMPANY INFORMATION Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Mobile Number Number/s [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Annual Meeting Fiscal Year No. of Stockholders Month/Day Month/Day 7,985 09/24 December 31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Mobile Number Number/s Ricardo B. Tan Jr. [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Contact Person’s Address ABS-CBN Broadcast Center, Sgt. Esguerra Avenue corner Mother Ignacia St. Quezon City Note: In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

ISTANBUL INTERNATIONAL SHORT FILM FESTIVAL 14-21 Aralık | December 2018

29. İSTANBUL ULUSLARARASI KISA FİLM FESTİVALİ 29th ISTANBUL INTERNATIONAL SHORT FILM FESTIVAL 14-21 Aralık | December 2018 www.istanbulfilmfestival.com Etkinlikler Ücretsizdir | Entrance is Free DÜZENLEME KURULU | ORGANISATION COMMITTEE Hilmi Etikan, Yıldız Etikan, Natali Yeres, Berna Kuleli, Haşmet Topaloğlu, Bahar Tırnakçı, Sinan Turan, Duygu Etikan DESTEKLERİ İÇİN TEŞEKKÜR EDERİZ | WE ARE GREATFUL FOR THEIR SUPPORT Matthieu Bardiaux, Christophe Pécot, Dr. Reimar Volker, Fügen Uğur, Gianni Vinciguerra, Tanju Şahan, Ioana Pavel, Aslı Ertürk, Aslı Selçuk, Emre Kurt, Esin Köymen, Fehime Koç, Gürhan Gezer, Mehmet Koç, Özlem Kurt, Selma Erdem, Sinan Ersin ULUSLARARASI FİLM SEÇKİSİ | INTERNATIONAL FILM SELECTION Hilmi Etikan, Belma Baş, Belmin Şöylemez, Berna Kuleli, Ömer Tuncer, Haluk Koçoğlu, Aslı Ertürk, İlker Canikligil, Ahmet Sönmez, Haşmet Topaloğlu, Ufuk Etikan, Bengü Üçüncü, Nazım Yılmaz ALTYAZI ÇEVİRİ | SUBTITLE TRANSLATION Emel Çelebi, Berna Kuleli, Deniz Üstüner, Aylin Özorhan, Güneş Karadeniz Grant, İlknur Boyer, Merve Uslucan Stolarz, Ufuk Etikan, Hande Alparslan, Can Usta, Duygu Etikan, Uğur Çınar Katalog Tasarımı | Catalogue Desing Sinan Turan Festival Fragman | Festival Trailer Duygu Etikan Teknik Ekip Sorumluları | Technical Team Coordinators Emre Yaşar, Süleyman Akşar, Bilal İncel Festival Adres | Festival Address Uluslararası İstanbul Kısa Film Festivali [email protected] www.istanbulfilmfestival.com İçindekiler | Contents ULUSAL JÜRİ | NATIONAL JURY 5 PROGRAM | PROGRAMME 6 KURMACA FİLMLER | FICTION FILMS 6 CANLANDIRMA FİLMLER | ANIMATION FILMS 126 DENEYSEL FİLMLER | EXPERIMENTAL FILMS 163 BELGESEL FİLMLER | DOCUMENTARY FILMS 174 Ulusal Jüri | National Jury Cem ALTINSARAY Henüz makina mühendisliği öğrencisiyken, Milliyet Dergi Grubu’nda, Duygu Asena yönetiminde çıkan “Negatif” dergisi kadrosuna katıldı ve basında çalışmaya başladı. Bu ilk deneyimin ardından Hürriyet bünyesinde “Sinerama”yı hazırlayan ekipte yer aldı. Sırasıyla, “Sinema” ve “Max” dergilerinde yazı işleri müdürü olarak görev yaptı. -

March 2020 March 2

March 2020 March 2 Cover design from the exhibit of Ms. Bing Famoso What’s UP? is a publication of the UP Diliman Information Office under the Office of the Chancellor, UP Diliman. Its editorial office is located at 2/F University Theater (Villamor Hall), Osmeña Avenue, UP Diliman, Quezon City, with telephone numbers Kasali Ka sa 8981-8500 loc. 3982/3983, email address [email protected]. Bagong Dekada What’s UP? accepts announcements of activities of UPD academic and administrative units and student organizations, as well as call for papers. Text should not exceed 400 words and must contain the event’s title, event’s information, venue, date and time, contact information of the organizing group and ticket price, if applicable. Photos should be in jpeg format, 200 dpi. Sir Anril P. Tiatco Mario Carreon 8:30 a.m. (exhibit opening) Editors Media Center Building, College of Bino C. Gamba Jr. Mass Communication Managing Editor Jefferson Villacruz With a theme A-TEN ‘TO, DZUP Layout Artist 1602 is holding a week-long exhibit to showcase their 10 Mariamme D. Jadloc Haidee C. Pineda fruitful years and their pursuit Benito V. Sanvictores Jr. of matinong usapan para sa Copy Editors maunlad na bayan. Narciso S. Achico Jr. Shirley S. Arandia The exhibit is free and open to Jacelle Isha B. Bonus the public. Pia Ysabel C. Cala Raul R. Camba Chi A. Ibay Anna Kristine E. Regidor Leonardo A. Reyes Evangeline C. Valenzuela Editorial Staff Schedules are subject to change without prior notice. For confirmation of program schedules, please coordinate with concerned organizers using the contact information indicated in each activity. -

The Philippines Are a Chain of More Than 7,000 Tropical Islands with a Fast Growing Economy, an Educated Population and a Strong Attachment to Democracy

1 Philippines Media and telecoms landscape guide August 2012 1 2 Index Page Introduction..................................................................................................... 3 Media overview................................................................................................13 Radio overview................................................................................................22 Radio networks..........……………………..........................................................32 List of radio stations by province................……………………………………42 List of internet radio stations........................................................................138 Television overview........................................................................................141 Television networks………………………………………………………………..149 List of TV stations by region..........................................................................155 Print overview..................................................................................................168 Newspapers………………………………………………………………………….174 News agencies.................................................................................................183 Online media…….............................................................................................188 Traditional and informal channels of communication.................................193 Media resources..............................................................................................195 Telecoms overview.........................................................................................209 -

Bayan Foundation: Helping Build the Nation from Below

June 2007 A forbirthday Meralco chairman surprise Manuel M. Lopez at the LAA...pp.4 & 8 Bayan Foundation: Helping 1Q 2007 fi nancial results: build the nation from below IN a town in La Union, it was report- But this story of transformation neurs—but also stewards of funds; they First Gen, ed that fewer people knocked on the actually goes back to a decade earlier, were able to pay their loans on time with doors of Bauang Private Power Corp. to a group of women living in a de- interest. That inspired ABS-CBN Foun- pinakamalakas (BPPC) to ask for donations. Sari-sari pressed area in Metro Manila. dation Inc. [AFI] under Gina Lopez to kumita...p.2 stores started sprouting, and residents In 1997, the Lopezes loaned 25 make microfi nance a regular program engaged each other in a friendly com- women from Loyola Heights, Quezon under the foundation,” says ABS-CBN petition to come up with the best pro- City a certain amount of money to be Bayan Foundation Inc.’s Irma Cosico. cessed meat and fi sh products. Most used for a small business of their choice. Armed with additional fund- surprising of all, local moneylend- They were asked to pay off the loan, with ing from the BPPC, ABS-CBN Bay- ers lowered the interest they charged interest, within a designated period. an headed north to La Union and residents to 10% from the customary “That initial step proved that wom- 20%. en can be good—not only entrepre- Turn to page 6 2 exhibits open at the Lopez Museum ...p.9 Back-to-school fi n d s @ P o w e r ...p.12 Passing on the values: A typical Bayan client in Quezon Plant Mall City as she involves her whole family in her enterprise. -

Philippines in View a CASBAA Market Research Report

Philippines in View A CASBAA Market Research Report An exclusive report for CASBAA Members Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 4 1.1 Pay-TV Operators 4 1.2 Pay-TV Subscriber Industry Estimates 5 1.3 Pay-TV Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) 5 1.4 Media Ownership of FTAs 6 1.5 Innovations and New Developments 6 1.6 Advertising Spend 6 1.7 Current Regulations 6 2 Philippine TV Market Overview 8 2.1 TV Penetration 8 2.2 Key TV Industry Players 9 2.3 Internet TV and Mobile TV 11 3 Philippine Pay-TV Structure 12 3.1 Pay-TV Penetration Compared to Other Countries 12 3.2 Pay-TV Subscriber Industry Estimates 12 3.3 Pay-TV Subscribers in the Philippines 13 3.4 Pay-TV Subscribers by Platform 14 3.5 Pay-TV Operators’ Market Share and Subscriber Growth 14 3.6 Revenue of Major Pay-TV Operators 16 3.7 Pay-TV Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) 17 3.8 Pay-TV Postpaid and Prepaid Business Model 17 3.9 Pay-TV Distributors 17 3.10 Pay-TV Content and Programming 18 3.11 Piracy in The Philippine Pay-TV Market 20 4 Overview of Philippine Free-To-Air (FTA) Broadcasting 21 4.1 Main FTA Broadcasters 21 4.2 FTA Content and Programming 26 5 Future Developments in the Philippine TV Industry 27 5.1 FTA Migration to Digital 27 5.2 New Developments and Existing Players 28 5.3 Emerging Players and Services 29 Table of Contents 6 Technology in the Philippine TV Industry 30 6.1 6.1 SKYCABLE 30 6.2 Cignal 30 6.3 G Sat 30 6.4 Dream 30 7 Advertising in the Philippine TV Industry 31 7.1 Consumer Affluence and Ability to Spend 31 7.2 General TV Viewing Behaviour 32 7.3 Pay-TV and -

Melissa Saldua Ventocilla LOVI POE SNOOKY

2016 DECEMBER Merry Christmas to Everyone UP PROF BLAST MARCOS National ID System Proposed EXHUMATION CALL: PH, Japan reaffirm maritime cooperation Respect the dead MANILA - Former President and initiated IDs into a single identifica- will be issued a Filipino ID Card that now Deputy Speaker Gloria Maca- tion system. MANILA - University of the Philippines (UP) pagal-Arroyo has filed a bill that Under House Bill No. 696, NATIONAL ID Political Science Professor Clarita Carlos is will integrate all government- Arroyo said all Filipino citizens continued on page 18 dismayed by calls to exhume former President Ferdinand Marcos’ body from the heroes’ cem- etery, noting that a wrong cannot be corrected by another wrong. “Don’t we have any more respect for dead people? It’s so sad really,” she said on “Mornings@ LOVI POE ANC” on Monday. “If you’re going to put all the blame on one Role Model of Kyla person when there were, in fact, you have a whole MARCOS SNOOKY continued on page 7 To Marry Her 60-Year Old Fiancee’ Camilineos TOGETHER AGAIN? JOHN LLOYD & ANGELICA PANAGANIBAN Melissa DON’T PAY THEM? Parking Tickets on private Lots, Anghel ng Tahanan contestant Nenita Lora poses with Camilineos President Harold Guarin at the Camilineos Saldua What To Do With Them year-end dinner party. Anghel Pageant Ventocilla Darren + Charms WALKS THE LUNIJO COLLECTION STANDING, Philippine Courier publisher Mon Datol, Senator Tobias Enverga, SITTING, GMA7’s Rosemer Charms singins group poses with Philippine singer Darren Enverga, Beth Bobila, Consul-General Rosalinda Pros- Espanto after the Sing Pilipinas Toronto competition. -

City of Screens

CITY OF SCREENS IMAGINING AUDIENCES IN MANILA’S ALTERNATIVE FILM CULTURE JASMINE NADUA TRICE CITY OF SCREENS CITY OF SCREENS IMAGINING AUDIENCES IN MANILA’S ALTERNATIVE FILM CULTURE JASMINE NADUA TRICE duke university press durham and london 2021 © 2021 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Cover designed by Drew Sisk Text designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Typeset in Chaparral by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Trice, Jasmine Nadua, [date] author. Title: City of screens : imagining audiences in Manila’s alternative film culture / Jasmine Nadua Trice. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2020021680 (print) lccn 2020021681 (ebook) isbn 9781478010586 (hardcover) isbn 9781478011699 (paperback) isbn 9781478021254 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Motion pictures—Philippines— Manila—Distribution. | Motion picture theaters— Philippines—Manila. | Independent films— Philippines—Manila. | Motion picture industry—Philippines—Manila. Classification:lcc pn1993.5.p6 t753 2021 (print) | lcc pn1993.5.p6 (ebook) | ddc 791.4309599/16—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020021680 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/20200 21681 Cover art: Map of Metro Manila, Philippines, adapted from the author’s website, cityofscreens.space. The interactive map charts film institutions, screening spaces, and film locations. For my mom, NANCY NADUA TRICE CONTENTS ACKNOWL EDGMENTS ix INTRODUCTION 1 ONE. Revanchist Cinemas 39 and Bad Audiences, Multiplex Fiestas and Ideal Publics TWO. The Quiapo Cinematheque and 79 Urban- Cinematic Authenticity THREE. Alternative Exhibition and 113 the Rhythms of the City FOUR. -

ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs

MARCH 2011 www.lopezlink.ph Happening on March 13! Story on page 10. www.facebook.com/pages/lopezlink www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs: New challenges PHOTO BY RYAN RAMOS REGINA “Ging” Reyes, formerly the ABS-CBN’s way the company delivered news and issues relevant to North America. Under her leadership, the news bureau North America Bureau chief, returned home to take the the Filipino community abroad. grew in scope, coverage and reputation. reins as senior vice president for News and Current Af- Voted one of the 100 Most Influential Filipino Women After her eight-year stint in North America, Reyes is fairs. As news bureau chief, Reyes initiated change and in the US, Reyes also covered breaking news, US politics, expected to ensure that all ABS-CBN News productions pioneered programs in the US, which have changed the and economic, immigration and veterans’ issues while in live up to world-class standards. Turn to page 6 The Grove ‘Dahil May Isang A Mt. Pico de Loro targets new market Ikaw’ nominated in adventure… page 10 segment…page 2 NYF Awards…page 4 Lopezlink March 2011 BIZ NEWS NEWS Lopezlink March 2011 The Grove to form a Lopez Holdings shareholders ABS-CBN to comm students: Lopez-backed AIM new skyline in Pasig Listen to your audience approve ESOP, ESPP ABS-CBN executives led by by media. renovation completed chairman and CEO Eugenio With the theme “Engaging SHAREHOLDERS of Lo- Lopez Holdings chairman knowledge can be built using synergies with affiliate SKY- “Gabby” Lopez III (EL3) re- People and Media Participation THE remod- pez Holdings Corporation in and chief executive Manuel such long-term incentive plans Cable Corporation and sister minded over 700 communi- for Change,” there were also eled Asian a special meeting approved M. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data.