City of Screens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPM Vol. 06 300 Songs

OPM Vol. 06 300 Songs Title Artist Number A WISH ON CHRISTMAS NIGHT JOSE MARI CHAN 22835 ADJUST SOAPDISH 28542 AGAC LA MANESIA PANGASINAN SONG 22999 AGAWAN BASE PERYODIKO 22906 AKALA KO AY IKAW NA WILLIE REVILLAME 22742 AKING PAGMAMAHAL REPABLIKAN 35077 AKO AY MAY LOBO CHILDREN 35115 AKO'Y BINAGO NIYA EUNICE SALDANA 35377 ALAB NG PUSO RIVERMAYA 27625 ALL ME TONI GONZAGA 35135 ALWAYS YOU CHARICE 28206 ANG AKING PUSO JANNO GIBBS feat. KYLA 28213 ANG HIMIG NATIN JUAN DELA CRUZ BAND 22690 ANG PANDAY ELY BUENDIA 22893 ANTUKIN RICO BLANCO 22838 ARAW-ARAW NA LANG AEGIS 22968 ASO'T PUSA HALE 28538 AWIT NG PUSO FATIMA SORIANO 22969 AYANG-AYANG BOSTON 22950 AYOKO SA DILIM FRANCIS MAGALONA 22751 AYUZ RICO BLANCO 22949 BABY DON'T YOU BREAK MY HEART SLOW M. Y. M. P. 22839 BACK 2 U CUESHE 28183 BAGONG HENERASYON HYMN JESSA MAE GABON 35052 BAHAY KUBO HALE 28539 BAHOO POKWANG 28182 BAKASYON PERYODIKO 22894 BAKIT GAGONG RAPPER 22729 BAKIT KUNG SINO PA GAGONG RAPPER 22725 BAKIT LABIS KITANG MAHAL GAGONG RAPPER 22744 BALASANG KAS NAN MONTANIOSA APOLLO FAGYAN 22963 BALITA GLOC 9 feat. GABBY ALIPE of URBA 22891 BALIW KISS JANE 35113 BANANA (RIGHT NOW) Tagalog Version BLANKTAPE 22747 BANGON RICO BLANCO 22890 BAR-IMAN TAUSUG 28184 BARKADA HABANG BUHAY CALSADA 35053 BAW WAW WAW FRANCIS MAGALONA 22773 BINIBINI BROWNMAN REVIVAL 22743 BONGGACIOUS POKWANG 22959 BULALAKAW HALE 28540 BUS STOP ELY BUENDIA & FRANCIS M. 35120 CAN'T FIND NO REASON LOUIE HEREDIA 22728 CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE SAM MILBY 22896 CHIKA LANG `YON BLANKTAPE 28202 CHRISTMAS BONUS AEGIS 35201 CHRISTMAS MORNING ERASERHEADS 35134 CHRISTMAS PARTY ERASERHEADS 35167 microky.com | 1 Title Artist Number COULD WE GARY V. -

Philippine Humanities Review, Vol. 13, No

The Politics of Naming a Movement: Independent Cinema According to the Cinemalaya Congress (2005-2010) PATRICK F. CAMPOS Philippine Humanities Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, December 2011, pp. 76- 110 ISSN 0031-7802 © 2011 University of the Philippines 76 THE POLITICS OF NAMING A MOVEMENT: INDEPENDENT CINEMA ACCORDING TO THE CINEMALAYA CONGRESS (2005-2010) PATRICK F. CAMPOS Much has been said and written about contemporary “indie” cinema in the Philippines. But what/who is “indie”? The catchphrase has been so frequently used to mean many and sometimes disparate ideas that it has become a confusing and, arguably, useless term. The paper attempts to problematize how the term “indie” has been used and defined by critics and commentators in the context of the Cinemalaya Film Congress, which is one of the important venues for articulating and evaluating the notion of “independence” in Philippine cinema. The congress is one of the components of the Cinemalaya Independent Film Festival, whose founding coincides with and is partly responsible for the increase in production of full-length digital films since 2005. This paper examines the politics of naming the contemporary indie movement which I will discuss based on the transcripts of the congress proceedings and my firsthand experience as a rapporteur (2007- 2009) and panelist (2010) in the congress. Panel reports and final recommendations from 2005 to 2010 will be assessed vis-a-vis the indie films selected for the Cinemalaya competition and exhibition during the same period and the different critical frameworks which panelists have espoused and written about outside the congress proper. Ultimately, by following a number PHILIPPINE HUMANITIES REVIEW 77 of key and recurring ideas, the paper looks at the key conceptions of independent cinema proffered by panelists and participants. -

1 Angel Locsin Prays for Her Basher You Can Look but Not Touch How

2020 SEPTEMBER Philippine salary among lowest in 110 countries The Philippines’ average salary of P15,200 was ranked as among the Do every act of your life as if it were your last. lowest in 110 countries surveyed by Marcus Aurelius think-tank Picordi.com. MANILA - Of the 110 bourg’s P198,500 (2nd), countries reviewed, Picodi. and United States’ P174,000 com said the Philippines’ (3rd), as well as Singapore’s IVANA average salary of P15,200 is P168,900 (5th) at P168,900, 95th – far-off Switzerland’s Alawi P296,200 (1st), Luxem- LOWEST SALARY continued on page 24 You can look but not Nostalgia Manila Metropolitan Theatre 1931 touch How Yassi Pressman turned a Triple Whammy Around assi Press- and feelings of uncertain- man , the ty when the lockdown 25-year- was declared in March. Yold actress “The world has glowed as she changed so much shared how she since the start of the dealt with the pandemic,” Yassi recent death of mused when asked her 90-year- about how she had old father, the YASSI shutdown of on page 26 ABS-CBN Philippines positions itself as the ‘crew PHL is top in Online Sex Abuse change capital of the world’ Darna is Postponed he Philippines is off. The ports of Panila, Capin- tional crew changes soon. PHL as Province of China label denounced trying to posi- pin and Subic Bay have all been It is my hope for the Phil- tion itself as a given the green light to become ippines to become a major inter- Angel Locsin prays for her basher crew change hub, crew change locations. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Naming

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Naming the Artist, Composing the Philippines: Listening for the Nation in the National Artist Award A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Neal D. Matherne June 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Sally Ann Ness Dr. Jonathan Ritter Dr. Christina Schwenkel Copyright by Neal D. Matherne 2014 The Dissertation of Neal D. Matherne is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This work is the result of four years spent in two countries (the U.S. and the Philippines). A small army of people believed in this project and I am eternally grateful. Thank you to my committee members: Rene Lysloff, Sally Ness, Jonathan Ritter, Christina Schwenkel. It is an honor to receive your expert commentary on my research. And to my mentor and chair, Deborah Wong: although we may see this dissertation as the end of a long journey together, I will forever benefit from your words and your example. You taught me that a scholar is not simply an expert, but a responsible citizen of the university, the community, the nation, and the world. I am truly grateful for your time, patience, and efforts during the application, research, and writing phases of this work. This dissertation would not have been possible without a year-long research grant (2011-2012) from the IIE Graduate Fellowship for International Study with funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. I was one of eighty fortunate scholars who received this fellowship after the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Program was cancelled by the U.S. -

Brillante Mendoza

Didier Costet presents A film by Brillante Mendoza SYNOPSIS Today Peping will happily marry the young mother of their newborn baby. For a poor police academy student, there is no question of turning down an opportunity to make money. Already accustomed to side profits from a smalltime drug ring, Peping naively accepts a well-paid job offer from a corrupt friend. Peping soon falls into an intense voyage into darkness as he experiences the kidnapping and torture of a beautiful prostitute. Horrified and helpless during the nightmarish all-night operation directed by a psychotic killer, Peping is forced to search within if he is a killer himself... CAST and HUBAD NA PANGARAP (1988). His other noteworthy films were ALIWAN PARADISE (1982), BAYANI (1992) and SAKAY (1993). He played in two COCO MARTIN (Peping) Brillante Mendoza films: SERBIS and KINATAY. Coco Martin is often referred to as the prince of indie movies in the Philippines for his numerous roles in MARIA ISABEL LOPEZ (Madonna) critically acclaimed independent films. KINATAY is Martin's fifth film with Brillante Mendoza after SERBIS Maria Isabel Lopez is a Fine Arts graduate from the (2008), TIRADOR/SLINGSHOT (2007), KALELDO/SUMMER University of the Philippines. She started her career as HEAT (2006) and MASAHISTA/ THE MASSEUR (2005). a fashion model. In 1982, she was crowned Binibining Martin's other film credits include Raya Martin's NEXT Pilipinas-Universe and she represented the Philippines ATTRACTION, Francis Xavier Pasion's JAY and Adolfo in the Miss Universe pageant in Lima, Peru. After her Alix Jr.'s DAYBREAK and TAMBOLISTA. -

Workplaces with the Rockwell Mother's May

MAY 2016 www.lopezlink.ph http://www.facebook.com/lopezlinkonline www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph Registration is ongoing! See details on page 10. #Halalan2016: All for the Filipino familyBy Carla Paras-Sison ABS-CBN Corporation launches its election coverage campaign about a year before election day. But it’s not protocol. Ging Reyes, head of ABS-CBN Integrated News and Current Affairs (INCA), says it actually takes the team a year to prepare for the elections. Turn to page 6 Workplaces with Mornings Mother’s the Rockwell with the May touch…page 2 ‘momshies’…page 4 …page 12 Lopezlink May 2016 Lopezlink May 2016 Biz News Biz News 2015 AUDITED FINANCIAL RESULTS Period Dispatch from Japan Total revenues Net income attributable to equity January- holders of the parent Building Mindanao’s September Workplaces with Design-driven PH products showcased in 2014 2015 % change 2014 2015 % change By John ALFS fest Porter ABS-CBN P33.544B P38.278B +14 P2.387B P2.932B +23 largest solar farm Lopez Holdings P99.191B P96.510B -3 P3.760B P6.191B +65 theBy Rachel Varilla Rockwell touch KIRAHON Solar Energy cure ERC [Energy Regulatory ing to the project’s success,” said EDC P30.867B P34.360B +11 P11.681B P7.642B -34 Corporation (KSEC) has for- Commission] approval and the KSEC CEO Mike Lichtenfeld. First Gen $1.903B $1,836B -4 $193.2M $167.3M -13 DELIVERING the same me- As the first mally inaugurated its 12.5- first to secure local nonrecourse Kirahon Solar Farm is First FPH P99.307B P96.643 -3 P5.632B P5.406B -4 ticulous standards it dedicated prime of- megawatt Kirahon Solar Farm debt financing, it was important Balfour’s second solar power ROCK P8.853B P8.922B +1 P1.563B P1.644B +5 to its residential developments, fice project of in Misamis Oriental. -

Advisory No. 002, S. 2020 January 03, 2020 in Compliance with Deped Order (DO) No

Advisory No. 002, s. 2020 January 03, 2020 In compliance with DepEd Order (DO) No. 8, s. 2013 this advisory is issued not for endorsement per DO 28, s. 2001, but only for the information of DepEd officials, personnel/staff, and the concerned public. (Visit www.deped.gov.ph) WINNERS OF THE 2019 METRO MANILA FILM FESTIVAL The 2019 Metro Manila Film Festival (MMFF) Gabi ng Parangal was held on December 27, 2019 at the New Frontier Theater in Araneta Center, Cubao, Quezon City. Mindanao a 2019 drama film produced under Center Stage Productions, and directed by Brillante Mendoza, won the top awards garnering the Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor for Allen Dizon, Best Actress for Judy Ann Santos, and Best Child Performer for Yuna Tangog . Judy Ann Santos played as Saima Datupalo, who cares for her cancer-stricken daughter Aisa (Yuna Tangog) while she awaits home for her husband Malang (Allen Dizon), a combat medic deployed to fight rebel forces in the southern Philppines. Their struggle is juxtaposed with the folklore of Rajah Indara Patra and Rajah Sulayman, the sons of Sultan Nabi, who fights to stop a dragon devastating Lanao. Mindanao also won six special MMFF award including FPJ Memorial Award for Excellence, Gatpuno Antonio J. Villegas Cultural Award, Best Visual Effects, Best Sound, Gender Sensitivity and Best Float Awards. The historical drama film Culion won the Special Jury Prize Award. Culion is directed by Alvin Yapan, starring Iza Calzado (Ana), Jasmine Curtis-Smith (Doris), and Meryll Soriano (Ditas). Set in the 1940s, the movie tells the story of three women seeking a cure for leprosy. -

Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary the Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959)

ISSN: 0041-7149 ISSN: 2619-7987 VOL. 89 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNITASSemi-annual Peer-reviewed international online Journal of advanced reSearch in literature, culture, and Society Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Antonio p. AfricA . UNITAS Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) . VOL. 89 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNITASSemi-annual Peer-reviewed international online Journal of advanced reSearch in literature, culture, and Society Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Antonio P. AfricA since 1922 Indexed in the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America Expressions of Tagalog Imgaginary: The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Copyright @ 2016 Antonio P. Africa & the University of Santo Tomas Photos used in this study were reprinted by permission of Mr. Simon Santos. About the book cover: Cover photo shows the character, Mercedes, played by Rebecca Gonzalez in the 1950 LVN Pictures Production, Mutya ng Pasig, directed by Richard Abelardo. The title of the film was from the title of the famous kundiman composed by the director’s brother, Nicanor Abelardo. Acknowledgement to Simon Santos and Mike de Leon for granting the author permission to use the cover photo; to Simon Santos for permission to use photos inside pages of this study. UNITAS is an international online peer-reviewed open-access journal of advanced research in literature, culture, and society published bi-annually (May and November). -

March 2020 Page 10

March 2020 Volume 12 No. 09 March 2020 Toyota President rides jeepneys and buses around Manila to experience the daily struggles of VIP Tour 2020 Filipino commuters Updates Page 18 Page 6 & 7 Merging pop culture Page 10 and Filipino heritage Houston’s Super Page 22 Realtor Page 2 DICK PHILS: DUTERTE: Billionaire GORDON: US terri- ‘No one Dennis Uy ‘Beware of tory or is fit to is looking the Fifth Chinese succeed for a Column’ province? me unicorn to Page 18 Page 19 Page 14 finance Page 23 02 March 2020 March 2020 03 De Numero Million US dollars, Opinions expressed herein are those amount hand-carried of the writers and do not necessarily reflect 160 into the country by the views of Chinese nationals ONE PHILIPPINES Texas edition for suspected laundering management and its editorial staff. Reproduction or use without permission of the publisher is stricly prohibited. “I will live and die with President Number of jobs lost Community news may be sent to ONE at Philippine Airlines PHILIPPINES Texas edition at Suite 170 Duterte. I will sink and swim with 300 as revenue losses 9898 Bissonnet Street, Houston TX. 77036. him…I am not plastic and say I This magazine is released once a month by continue to mount amid declining AZ Media Entertainment Services. don’t have any bias. I’m a real demand because of the COVID-19 person and say that I am biased outbreak. BHONG ZAUSA towards the president.” – Senator Publisher RONALD ‘BATO’ DELA ROSA, Billion pesos, on the issues of the Visiting Forces budget deficit of JAY R Agreement (VFA) abrogation and 660.2 the government Marketing Director the political destruction of ABS- last year, a result of spending more on CBN, making his position crystal education and services despite falling tax RAFAEL VIGILIA clear that he serves Duterte first and foremost and the collection Marketing Officer Constitution and the Filipino people only incidentally. -

At Last, Filipino Cinema in Portugal July 10, 2013/ Tiago Gutierrez Marques

At Last, Filipino Cinema in Portugal July 10, 2013/ Tiago Gutierrez Marques A scene from Brillante Mendoza's "Captive" (Source: filmfilia.com) I didn't know anything about Filipino cinema until very recently, as it’s practically unheard of in Portugal where most people don't even know where the Philippines is on the world map. But there are signs of change. In 2010 a Portuguese cultural association called “Zero em Comportamento” (Zero Behavior), which is dedicated to the dissemination of movies that fall outside the mainstream commercial cinema, organized a four-day retrospective showing in Lisbon of movies directed by acclaimed Filipino director Brillante Mendoza. This also included a masterclass on independent filmmaking in the Philippines, for cinema students and professionals (http://zeroemcomportamento.wordpress.com/arquivo/bmendoza/). This rare opportunity got me very excited, and particularly my Portuguese father, who went to see almost all of the eight movies. At the end of each showing, the audience could directly ask Brillante Mendoza their questions. And just a few months ago, one of Mendoza's latest films, “Captive,” was released in commercial theaters in Lisbon and Porto (Portugal's second city) alongside the usual Hollywood blockbusters. I couldn't believe that we had reached a new milestone for Filipino cinema in Portugal. Director Brillante Mendoza won the Palme d'Or at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival for "Kinatay." (Source: Bauer Griffin) “Captive” is about the kidnapping of a group of tourists by the fearsome Abu Sayaf group from a resort in Honda Bay, in Palawan. They are taken to Mindanao. -

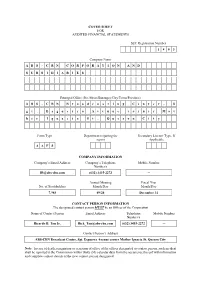

COVER SHEET for AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A

COVER SHEET FOR AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A B S - C B N C O R P O R A T I O N A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S Principal Office (No./Street/Barangay/City/Town/Province) A B S - C B N B r o a d c a s t i n g C e n t e r , S g t . E s g u e r r a A v e n u e c o r n e r M o t h e r I g n a c i a S t . Q u e z o n C i t y Form Type Department requiring the Secondary License Type, If report Applicable A A F S COMPANY INFORMATION Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Mobile Number Number/s [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Annual Meeting Fiscal Year No. of Stockholders Month/Day Month/Day 7,985 09/24 December 31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Mobile Number Number/s Ricardo B. Tan Jr. [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Contact Person’s Address ABS-CBN Broadcast Center, Sgt. Esguerra Avenue corner Mother Ignacia St. Quezon City Note: In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated. -

The Prospectus Is Being Displayed in the Website to Make the Prospectus Accessible to More Investors. the Pse Assumes No Respons

THE PROSPECTUS IS BEING DISPLAYED IN THE WEBSITE TO MAKE THE PROSPECTUS ACCESSIBLE TO MORE INVESTORS. THE PSE ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CORRECTNESS OF ANY OF THE STATEMENTS MADE OR OPINIONS OR REPORTS EXPRESSED IN THE PROSPECTUS. FURTHERMORE, THE STOCK EXCHANGE MAKES NO REPRESENTATION AS TO THE COMPLETENESS OF THE PROSPECTUS AND DISCLAIMS ANY LIABILITY WHATSOEVER FOR ANY LOSS ARISING FROM OR IN RELIANCE IN WHOLE OR IN PART ON THE CONTENTS OF THE PROSPECTUS. ERRATUM Page 51 After giving effect to the sale of the Offer Shares and PDRs under the Primary PDR Offer (at an Offer price of=8.50 P per Offer Share and per PDR) without giving effect to the Company’s ESOP, after deducting estimated discounts, commissions, estimated fees and expenses of the Combined Offer, the net tangible book value per Share will be=1.31 P per Offer Share. GMA Network, Inc. GMA Holdings, Inc. Primary Share Offer on behalf of the Company of 91,346,000 Common Shares at a Share Offer Price of=8.50 P per share PDR Offer on behalf of the Company of 91,346,000 PDRs relating to 91,346,000 Common Shares and PDR Offer on behalf of the Selling Shareholders of 730,769,000 PDRs relating to 730,769,000 Common Shares at a PDR Offer Price of=8.50 P per PDR to be listed and traded on the First Board of The Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc. Sole Global Coordinator, Bookrunner Joint Lead Manager, Domestic Lead Underwriter and Lead Manager and Issue Manager Participating Underwriters BDO Capital & Investment Corporation First Metro Investment Corporation Unicapital Incorporated Abacus Capital & Investment Corporation Pentacapital Investment Corporation Asian Alliance Investment Corporation RCBC Capital Corporation UnionBank of the Philippines Domestic Selling Agents The Trading Participants of the Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc.