Popular Song in Britain and in France in 1915 : Processes and Repertoires John Mullen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cold Chisel to Roll out the Biggest Archival Release in Australian Music History!

Cold Chisel to Roll Out the Biggest Archival Release in Australian Music History! 56 New and Rare Recordings and 3 Hours of Previously Unreleased Live Video Footage to be Unveiled! Sydney, Australia - Under total media embargo until 4.00pm EST, Monday, 27 June, 2011 --------------------------------------------------------------- 22 July, 2011 will be a memorable day for Cold Chisel fans. After two years of exhaustively excavating the band's archives, 22 July will see both the first- ever digital release of Cold Chisel’s classic catalogue as well as brand new deluxe reissues of all of their CDs. All of the band's music has been remastered so the sound quality is better than ever and state of the art CD packaging has restored the original LP visuals. In addition, the releases will also include previously unseen photos and liner notes. Most importantly, these releases will unleash a motherlode of previously unreleased sound and vision by this classic Australian band. Cold Chisel is without peer in the history of Australian music. It’s therefore only fitting that this reissue program is equally peerless. While many major international artists have revamped their classic works for the 21st century, no Australian artist has ever prepared such a significant roll out of their catalogue as this, with its specialised focus on the digital platform and the traditional CD platform. The digital release includes 56 Cold Chisel recordings that have either never been released or have not been available for more than 15 years. These include: A “Live At -

Mick Evans Song List 1

MICK EVANS SONG LIST 1. 1927 If I could 2. 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Here Without You 3. 4 Non Blondes What’s Going On 4. Abba Dancing Queen 5. AC/DC Shook Me All Night Long Highway to Hell 6. Adel Find Another You 7. Allan Jackson Little Bitty Remember When 8. America Horse with No Name Sister Golden Hair 9. Australian Crawl Boys Light Up Reckless Oh No Not You Again 10. Angels She Keeps No Secrets from You MICK EVANS SONG LIST Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again 11. Avicii Hey Brother 12. Barenaked Ladies It’s All Been Done 13. Beatles Saw Her Standing There Hey Jude 14. Ben Harper Steam My Kisses 15. Bernard Fanning Song Bird 16. Billy Idol Rebel Yell 17. Billy Joel Piano Man 18. Blink 182 Small Things 19. Bob Dylan How Does It Feel 20. Bon Jovi Living on a Prayer Wanted Dead or Alive Always Bead of Roses Blaze of Glory Saturday Night MICK EVANS SONG LIST 21. Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the dark I’m on Fire My Home town The River Streets of Philadelphia 22. Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Heaven Run to You Cuts Like A Knife When You’re Gone 23. Bush Glycerine 24. Carly Simon Your So Vein 25. Cheap Trick The Flame 26. Choir Boys Run to Paradise 27. Cold Chisel Bow River Khe Sanh When the War is Over My Baby Flame Trees MICK EVANS SONG LIST 28. Cold Play Yellow 29. Collective Soul The World I know 30. Concrete Blonde Joey 31. -

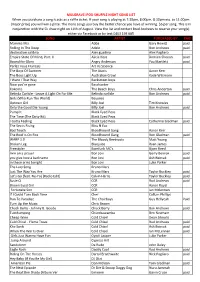

MULGRAVE IPOD SHUFFLE NIGHT SONG LIST When You Purchase a Song It Acts As a Raffle Ticket

MULGRAVE IPOD SHUFFLE NIGHT SONG LIST When you purchase a song it acts as a raffle ticket. If your song is playing at 7:30pm, 8:00pm, 8:30pm etc. to 11:00pm (major prize) you will win a prize. The more songs you buy the better chance you have of winning. $5 per song. This is in conjunction with the 5k draw night on 11th of August. View the list and contact Brad Andrews to reserve your song(s) either via Facebook or by text 0403 193 085 SONG ARTIST PURCHASED BY PAID Mamma Mia Abba Gary Hewitt paid Rolling In The Deep Adele Bon Andrews paid destination calibria Alex guadino Alex Pagliaro Empire State Of Mind, Part. II Alicia Keys Damien Sheean paid Bound for Glory Angry Anderson Paul Bartlett paid Parlez Vous Francais Art Vs Science The Boys Of Summer The Ataris Aaron Kerr The Boys Light Up Australian Crawl Kade Wilsmore I Want I That Way Backstreet boys Now you're gone Basshunter Kokomo The Beach Boys Chris Anderton paid Belinda Carlisle ‐ Leave A Light On For Me Belinda carlisle Bon Andrews paid Girls (Who Run The World) Beyonce Uptown Girl Billy Joel Tim Knowles Only the Good Die Young Billy Joel Bon Andrews paid Pump It Black Eyed Peas The Time (The Dirty Bit) Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Catherine Gladman paid The Sea is Rising Bliss N Eso Bad Touch Bloodhound Gang Aaron Kerr The Roof Is On Fire Bloodhound Gang Ron Gladman paid WARP 1.9 The Bloody Beetroots Matt Young Broken Leg Bluejuice Ryan James Freestyler Bomfunk MC's Bjorn Reed livin on a prayer Bon Jovi Gerry Beiniak paid you give love a bad name Bon Jovi Ash Beiniak paid in these arms tonight Bon Jovi Luke Parker The Lazy Song Bruno Mars Just The Way You Are Bruno Mars Taylor Buckley paid Let's Go (feat. -

Robbie Williams Another Saturday Night

Classic Pop / Dance A little less conversation - Elvis Angels - Robbie Williams Let's dance - Chris Rea Another Saturday night - Sam Cook Let's groove tonight - Earth wind n fire Baby did a bad bad thing - Chris Isaac Let's stick together - Bryan Ferry Better be home soon - Crowded House Life is a rollercoaster - Ronan Keating Big Yellow Taxi - Counting Crows Lips of an Angel - Hinder Billy Jean - Michael Jackson Love foolosophy - Jamiroquai Black fingernails - Eskimo Joe love is in the air - John Paul Young Blame it the Boogie - Jacksons Love really hurts without you - Billy Ocean Born to be Alive - Patrick Hernandez Love shack - B52's Boys of Summer - The Ataris Love the one you're with - Luther Vandross Brandy - Looking Glass Make Luv - Room 5 Bright side of the road - Van Morrison Makes me wonder - Maroon 5 Breakfast at Tiffanys - Deep blue something Man I feel like a woman - Shania Twain Cable Car - The Fray New York - Eskimo Joe Can't get enough of you baby - smashmouth No such thing - John Mayer Catch my disease - Ben Lee Not in Love - Enrique Iglesius Celebration - Kool and the Gang On the Beach - Chris rea Chain Reaction - John Farnham One more time - Britney Spears Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol Play that funky music - Average white band Cheap Wine - Cold Chisel Pretty Vegas - INXS Cherry cherry - Neil Diamond Rehab - Amy Winehouse Choir Girl - Cold Chisel Save the last dance for me - Michael Buble Clocks - Coldplay Second Chance - Shinedown NEW Closing time - Semisonic September - Earth wind and fire Come undone - Robbie Williams -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

ADJS Top 200 Song Lists.Xlsx

The Top 200 Australian Songs Rank Title Artist 1 Need You Tonight INXS 2 Beds Are Burning Midnight Oil 3 Khe Sanh Cold Chisel 4 Holy Grail Hunter & Collectors 5 Down Under Men at Work 6 These Days Powderfinger 7 Come Said The Boy Mondo Rock 8 You're The Voice John Farnham 9 Eagle Rock Daddy Cool 10 Friday On My Mind The Easybeats 11 Living In The 70's Skyhooks 12 Dumb Things Paul Kelly 13 Sounds of Then (This Is Australia) GANGgajang 14 Baby I Got You On My Mind Powderfinger 15 I Honestly Love You Olivia Newton-John 16 Reckless Australian Crawl 17 Where the Wild Roses Grow (Feat. Kylie Minogue) Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds 18 Great Southern Land Icehouse 19 Heavy Heart You Am I 20 Throw Your Arms Around Me Hunters & Collectors 21 Are You Gonna Be My Girl JET 22 My Happiness Powderfinger 23 Straight Lines Silverchair 24 Black Fingernails, Red Wine Eskimo Joe 25 4ever The Veronicas 26 Can't Get You Out Of My Head Kylie Minogue 27 Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun 28 Sweet Disposition The Temper Trap 29 Somebody That I Used To Know Gotye 30 Zebra John Butler Trio 31 Born To Try Delta Goodrem 32 So Beautiful Pete Murray 33 Love At First Sight Kylie Minogue 34 Never Tear Us Apart INXS 35 Big Jet Plane Angus & Julia Stone 36 All I Want Sarah Blasko 37 Amazing Alex Lloyd 38 Ana's Song (Open Fire) Silverchair 39 Great Wall Boom Crash Opera 40 Woman Wolfmother 41 Black Betty Spiderbait 42 Chemical Heart Grinspoon 43 By My Side INXS 44 One Said To The Other The Living End 45 Plastic Loveless Letters Magic Dirt 46 What's My Scene The Hoodoo Gurus -

Rachel Laing Song List - Updated 28 02 2019

RACHEL LAING SONG LIST - UPDATED 28 02 2019 SONG TITLE ORIGINAL ARTIST VERSION (IF NOT ORIGINAL) 3AM MATCHBOX 20 100 YEARS FIVE FOR FIGHTING 500 MILES (I'M GONNA BE) THE PROCLAIMERS 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ A HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA A THOUSAND MILES VANESSA CARLTON A THOUSAND YEARS CHRISTINA PERRI A WHITE SPORTS COAT MARTY ROBBINS ABOVE GROUND NORAH JONES ADORN MIGUEL ADVANCE AUSTRALIA FAIR NATIONAL ANTHEM AHEAD OF MYSELF JAMIE LAWSON AINT NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERS ALIVE SIA ALL ABOUT THAT BASS MEGHAN TRAINOR ALL OF ME JOHN LEGEND ALL THE SMALL THINGS BLINK 182 ALL TIME LOW JOHN BELLION ANDY GRAMMER ALWAYS ON MY MIND ELVIS AM I EVER GONNA SEE YOUR FACE AGAIN THE ANGELS RACHEL LAING AM I NOT PRETTY ENOUGH KASEY CHAMBERS AM I WRONG NICO & VINZ AMAZING GRACE AND THE BOYS ANGUS & JULIA STONE ANGEL SARAH MCLAUGHLAN ANGELS ROBBIE WILLIAMS ANNIES SONG JOHN DENVER ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE PHIL COLLINS APOLOGIZE ONE REPUBLIC APRIL SUN IN CUBA DRAGON ARE YOU GONNA BE MY GIRL JET ARE YOU OLD ENOUGH DRAGON ARMY OF TWO OLLY MURS AT LAST ETTA JAMES AULD LANG SYNE AUTUMN LEAVES NAT KING COLE EVA CASSIDY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU TRACEY CHAPMAN BACK TO DECEMBER TAYLOR SWIFT BAD MOON RISING CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL BAIL ME OUT PETE MURRAY BASKET CASE SARA BARELLIS BE HERE TO LOVE ME NORAH JONES BE MY SOMEBODY NORAH JONES BEAUTIFUL IN MY EYES JOSHUA KADISON BESEME MUCHO BEST FRIENDS BRANDY BETTE DAVIS EYES KIM CARNES BETTER BE HOME SOON CROWDED HOUSE BETTER MAN PEARL JAM BETTER THAN JOHN BUTLER TRIO BIG DEAL LEANNE RIMES BIG JET PLANE ANGUS & JULIA STONE -

Poco Loco Song List Newly Added Music Classic Pop / Dance

Poco Loco Song List Newly added Music Just the way you are - Bruno Mars Break even - The Script Closer - Chris Brown Love Story - Taylor Swift Forget you - Cee Lo Green Cry for you - September Pack up - Eliza Doolittle The boy does nothing - Alesha Dixon OMG - Usher Mercy - Duffy I've got a feeling - Black eyed Peas Rain - Dragon Bad Romance - Lady Ga Ga Dakota - Stereophonics Poker face - Lady Ga Ga California Gurls - Katy Perry Alejandro - Lady Ga Ga Don't hold Back - Pot Beleez I'm yours - Jason Mraz Sex on Fire - Kings of Leon Hey Soul Sister - Train Like it like that - Guy Sebastian Escape(The Pina Colada Song Smile - Uncle Kracker Sweet about me - Gabriella Cilma Save the lies - Gabriella Cilmi Apologize - One Republic Black and Gold - Sam Sparro Classic Pop / Dance A little less conversation - Elvis Let's dance - Chris Rea Addicted to Bass - Amiel Let's get the party started - Pink Ain't nobody - Chaka Khan Let's groove tonight - Earth wind n fire All I wanna do - Sheryl Crow Lets hear it for the boy - Denise Williams Amazing - George Michael Let's stick together - Bryan Ferry Angels - Robbie Williams Life is a rollercoaster - Ronan Keating Another Saturday night - Sam Cook Love at first sight - Kylie Minogue Around the the world - Lisa Stanfield Love fool - Cardigans Baby did a bad bad thing - Chris Isaac Love foolosophy - Jamiroquai Bad girls - Donna Summer love is in the air - John Paul Young Beautiful - Disco Montego Love really hurts without you - Billy Ocean Believe - Cher Love shack - B52's Bette Davis eyes - Kim Carnes -

Stephen Foster and American Song a Guide for Singers

STEPHEN FOSTER AND AMERICAN SONG A Guide for Singers A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Samantha Mowery, B.A., M.M. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Dr. Robin Rice, Advisor Approved By Professor Peter Kozma ____________________ Dr. Wayne Redenbarger Advisor Professor Loretta Robinson Graduate Program in Music Copyright Samantha Mowery 2009 ABSTRACT While America has earned a reputation as a world-wide powerhouse in area such as industry and business, its reputation in music has often been questioned. Tracing the history of American folk song evokes questions about the existence of truly American song. These questions are legitimate because our country was founded by people from other countries who brought their own folk song, but the history of our country alone proves the existence of American song. As Americans formed lives for themselves in a new country, the music and subjects of their songs were directly related to the events and life of their newly formed culture. The existence of American song is seen in the vocal works of Stephen Collins Foster. His songs were quickly transmitted orally all over America because of their simple melodies and American subjects. This classifies his music as true American folk-song. While his songs are simple enough to be easily remembered and distributed, they are also lyrical with the classical influence found in art song. These characteristics have attracted singers in a variety of genres to perform his works. ii Foster wrote over 200 songs, yet few of those are known. -

Australian and New Zealand Karaoke Song Book

Australian & NZ Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 1927 Allison Durbin If I Could CKA16-06 Don't Come Any Closer TKC14-03 If I Could TKCK16-02 I Have Loved Me A Man NZ02-02 ABBA I Have Loved Me A Man TKC02-02 Waterloo DU02-16 I Have Loved Me A Man TKC07-11 AC-DC Put Your Hand In The Hand CKA32-11 For Those About To Rock TKCK24-01 Put Your Hand In The Hand TKCK32-11 For Those About To Rock We Salute You CKA24-14 Amiel It's A Long Way To The Top MRA002-14 Another Stupid Love Song CKA22-02 Long Way To The Top CKA04-01 Another Stupid Love Song TKC22-15 Long Way To The Top TKCK04-08 Another Stupid Love Song TKCK22-15 Thunderstruck CKA18-18 Anastacia Thunderstruck TKCK18-01 I'm Outta Love CKA13-04 TNT CKA21-03 I'm Outta Love TKCK13-01 TNT TKCK21-01 One Day In Your Life MRA005-15 Whole Lotta Rosie CKA25-10 Androids, The Whole Lotta Rosie TKCK25-01 Do It With Madonna CKA20-12 You Shook Me All Night Long CKA01-11 Do It With Madonna TKCK20-02 You Shook Me All Night Long DU01-15 Angels, The You Shook Me All Night Long TKCK01-10 Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again CKA01-03 Adam Brand Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again TKCK01-08 Dirt Track Cowboy CKA28-17 Dogs Are Talking CKA30-17 Dirt Track Cowboy TKCK28-01 Dogs Are Talking TKCK30-01 Get Loud CKA29-17 No Secrets CKA33-02 Get Loud TKCK29-01 Take A Long Line CKA05-01 Good Friends CKA28-09 Take A Long Line TKCK05-02 Good Friends TKCK28-02 Angus & Julia Stone Grandpa's Piano CKA19-14 Big Jet Plane CKA33-05 Grandpa's Piano TKCK19-07 Anika Moa Last Man Standing CKA14-13 -

We're Still Here

Si Kahn We’re Still Here o measure the success of a folk e’re Still Here is a tribute to Tsongwriter, the usual pop yardsticks are useless, like using a level to measure Wthe persistence and resistance a river. Count Si Kahn’s career in Grammies, Billboard bullets, MTV of working people everywhere. videos, or wardrobe malfunctions, and you miss him entirely. Flying overhead is the spirit of the But by the unique, timeless, grassrootsy measures with which great folk songs great labor radical Mother Jones, have always been judged, it can be born Mary Harris in County Cork, argued that he is the most successful folk songwriter of his generation. This Ireland about 1836. is all the more remarkable, given that he is also among the most unrepentantly The Road To Wigan Pier by George Orwell radical political songwriters of his age. exposed working and living conditions in English mining villages in the 1930s. “Colliery” is British His songs have been recorded by over English for coal mine. The cable that lowers the 100 artists, including some of the most miners’ cage down into the shaft is powered by the respected voices in folk music today: “colliery wheel.” “Davey Lamps” are early miners’ June Tabor and the Oyster Band, Robin safety lamps. Coxey’s Army of unemployed workers, and Linda Williams, Dick Gaughan, having marched to Washington, DC from around John McCutcheon, Laurie Lewis, Irish the country, gathered on Capitol Hill on May singing legend Dolores Keane, and Day, 1894 to demand public works jobs. Celtic groups Planxty, the Fureys, and Patrick Street. -

Songster of The

SONGSTER OF THE PALMETTO RIFLEMEN & NEW YORK ZOUAVES The Company Songster of the Palmetto Riflemen and New York Zouaves i SONGSTER OF THE Palmetto Riflemen & New York Zouaves Prepared by the Committee on Military Instruction and Lecture Introduction “All history proves that music is as indispensable to warfare as money; and money has been called the sinews of war. Music is the soul of Mars...” – The New York Herald, 1862. This “Songster” has been created for the membership of the “Palmetto Riflemen” & “New York Zouaves” as a Song Book to be used in the camp, around the fire, on the field, and all other places. Efforts have been made to try and make sure that all of the songs included herein were written prior to 1865 and as such would have been heard in the armies of the United and Confederate States during the conflict. Some of these songs may be considered inappropriate by today’s standards, such as ethnic parodies and racial references, however it should be remembered that during the conflict these were commonplace and were considered as acceptable public entertainment, and should be used in a historical context such as reenactments and living histories. * * * * * * * * * * * * Music was important throughout the war and played a large part in the daily lives of the soldiers of both armies. From buglers, drummers, and fifers playing the various calls to duty or orders; the regimental or brigade bands that played inspiring music while on the march or in the fight; and the soldiers themselves singing in camp as a diversion from the humdrum of daily life.