Broadcasting Industry Ethics, the First Amendment and Televised Violencel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boynton Beach ALF (SCA 2020-008)

Item: III.A.1 FUTURE LAND USE ATLAS AMENDMENT STAFF REPORT SMALL SCALE AMENDMENT PLANNING COMMISSION PUBLIC HEARING, MAR. 13, 2020 A. Application Summary I. General Project Name: Boynton Beach Assisted Living Facility (SCA 2020-008) Request: CL/3 to CL-O/CLR Acres: 3.59 acres Location: South side of Woolbright Road, 250 feet west of South Jog Road Project Manager: Gerald Lodge, Planner 1 Applicant: HDRS, LLC Owner: Hardial Sibia Agent: Gentile Glas Holloway O’Mahoney & Associates, Inc. Staff Staff recommends approval with conditions based upon the following Recommendation: findings and conclusions contained in this report. II. Assessment & Conclusion The amendment proposes to change the future land use designation on a 3.59 acre site from Commercial Low with an underlying Low Residential, 3 units per acre (CL/3) to Commercial Low- Office with an underlying Congregate Living Residential (CL-O/CLR) to facilitate the development of a congregate living facility (CLF). The amendment proposes to change the allowable density from 3 to 8 units per acre for the calculation of a higher bed count, for a maximum of 69 beds. The applicant is proposing a condition to limit the site to a maximum of 8 units per acre, for the purposes of calculating CLF beds. In addition, the amendment proposes to change the commercial future land use from CL to CL- O. In 2007, the CL designation was approved with a condition limiting the site to a maximum of 50,000 sq. ft. of non-retail uses only. The applicant wants to retain a Commercial designation for the option to develop office uses as an alternative. -

A FOURTH GRADE EXPERIENCE Donald G. Saari Northwestern University, Departments of Mathematics and of Economics August, 1991

A FOURTH GRADE EXPERIENCE Donald G. Saari Northwestern University, Departments of Mathematics and of Economics August, 1991 “We’ve been trying to tell you you’re wrong!” With this severe reprimand, a fourth- grade girl, hand on hip, expressed the class’ growing exasperation with the slow witted mathematics professor who couldn’t understand the obvious. Dr. Diane Briars, Director of Mathematics, invited me to discuss modern mathematics with the teachers and several student groups as part of the Pittsburgh Public Schools’ observance of the national “Mathematics Awareness Week.” It was easy to prepare for classes fromtheeighthgradeon–agrabbagofunexpectedexamplesfrom“chaos,” mathematical astronomy, properties of surfaces, and statistical paradoxes could illustrate mathematical themes while capturing their imagination. But I fought to disguise my growing panic when informed that I was to talk to a fourth grade class. What does one say to fourth graders? It didn’t help to discover on arrival at the East Hill’s Elementary School that the core of my intended audience, Ms. Chamberlain’s class of very young children, all were sufficiently short to inspire extreme caution while walking about. I have found that the mathematics of decision making – in particular, voting – serves as a useful vehicle to introduce a variety of mathematical concepts starting with elementary counting, to algebra and geometry, and then, on a research level, certain delicate mathe- matical symmetries. So, I figured I could survive my allotted forty minutes by describing a counting problem caused by a voting example. The posed problem involved an hypothetical group of fifteen children permitted to watch only one TV show for the evening. -

Assisted Living Facility Directory

AGENCY FOR HEALTH CARE ADMINISTRATION ASSISTED LIVING FACILITY DIRECTORY Date: 8/1/2018 OSS Beds = 11,337 Private Beds = 91,015 Total Facilities = 3,091 FIELD OFFICE: 01 OSS BEDS = 128 PRIVATE BEDS = 3096 FACILITIES = 52 COUNTY: OSS BEDS = 108 PRIVATE BEDS = 1386 FACILITIES = 25 ESCAMBIA License #9099 ASBURY PLACE LIC TYPE : ALF Expiry: 9/16/2018 4916 MOBILE HIGHWAY CAPACITY : 64 12:00:00 AM PENSACOLA, FL 32506 OSS BEDS : 0 PRIVATE BEDS : (850) 495-3920 ADM: Ervin, Billy 64 File #11964608 OWNER : Asbury Pensacola PLC LLC License #9576 BROADVIEW ASSISTED LIVING FACILITY LIC TYPE : ALF ECC Expiry: 7/10/2019 2310 ABBIE LANE CAPACITY : 72 12:00:00 AM PENSACOLA, FL 32514 OSS BEDS : 0 PRIVATE BEDS : (850) 505-0111 ADM: CARMACK, KAYLA 72 File #11965185 OWNER : SSA PENSACOLA ALF, LLC License #9354 BROOKDALE PENSACOLA LIC TYPE : ALF LNS Expiry: 9/13/2020 8700 UNIVERSITY PARKWAY CAPACITY : 60 12:00:00 AM PENSACOLA, FL 32514 OSS BEDS : 0 PRIVATE BEDS : (850) 484-9500 ADM: HODSON, JENNIFER 60 File #11964959 OWNER : BROOKDALE SENIOR LIVING COMMUNITIES, INC. License #11667 EMERALD GARDENS PROPERTIES, LLC LIC TYPE : ALF LNS Expiry: 10/4/2019 1012 N 72 AVENUE CAPACITY : 55 12:00:00 AM PENSACOLA, FL 32506 OSS BEDS : 0 PRIVATE BEDS : (850) 458-8558 ADM: MILLER, KRISTINA 55 File #11967671 OWNER : EMERALD GARDENS PROPERTIES, LLC. License #5153 ENON COUNTRY MANOR ALF LLC LIC TYPE : ALF LMH Expiry: 1/10/2019 7701 ENON SCHOOL RD CAPACITY : 25 12:00:00 AM WALNUT HILL, FL 32568-1531 OSS BEDS : 10 PRIVATE BEDS (850) 327-4867 ADM: Hall, Tamron : 15 File #11910468 -

Federal Communications Commission DA 07-1258 Before The

Federal Communications Commission DA 07-1258 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 ) In the matter of ) ) Lorillard Tobacco Company ) ) DA 01-2565 Motion for Declaratory Ruling Re: Section ) ) 73.1206 of the Commission’s Rules ) ) ORDER Adopted: March 12, 2007 Released: March 13, 2007 By the Chief, Media Bureau: I. INTRODUCTION 1. Lorillard Tobacco Company (“Lorillard”) filed a Motion for Declaratory Ruling (“Motion”) regarding application of the Commission’s rule concerning the broadcast of telephone conversations.1 The American Legacy Foundation (“ALF”) filed an Opposition to Lorillard’s Motion,2 and Lorillard responded.3 Broadcasters, public interest groups and other interested parties filed comments, and ALF and Lorillard submitted reply comments.4 For the reasons discussed below, we deny Lorillard’s Motion. II. BACKGROUND 2. In its motion, Lorillard asks that we rule that: (1) Section 73.1206 of the Commission’s rules5 prohibits the broadcast of an advertisement or other programming material supplied to a broadcast 1 Motion for Declaratory Ruling filed by Lorillard Tobacco Company (October 1, 2001). The Mass Media Bureau released a Public Notice seeking comment on Lorillard’s Motion. Public Notice, DA 01-2565 (Nov. 5, 2001); Public Notice, Erratum, replacing Public Notice dated November 5, 2001 (Nov. 7, 2001). 2 Opposition of ALF (October 16, 2001). 3 Response of Lorillard (October 26, 2001). 4 See Appendix A for a list of filings in this matter. 5 Section 73.1206 provides that: Before recording a telephone conversation for broadcast, or broadcasting such a conversation simultaneously with its occurrence, a licensee shall inform any party to the call of the licensee’s intention to broadcast the conversation, except where such party is aware, or may be presumed to be aware from the circumstances of the conversation, that it is being or likely will be broadcast. -

AMF / ALF SERIES Albedometer Mounting and Levelling Fixtures: Combine 2 Pyranometers Into 1 Albedometer with Our AMF03 and AMF02 Albedometer Kits

Hukseflux Thermal Sensors ACCESSORY AMF / ALF SERIES Albedometer mounting and levelling fixtures: combine 2 pyranometers into 1 albedometer with our AMF03 and AMF02 albedometer kits Hukseflux offers a practical range of mounting and levelling fixtures to construct albedometers from its popular pyranometers and make installation and levelling easy. Albedometers are increasingly popular in bifacial PV module monitoring. AMF03 allows you to combine two SR30-M2-D1 spectrally flat Class A pyranometers or two SR15 series Class B pyranometers into one albedometer. AMF02 does so for two SR11 or two SR20 series pyranometers. The modular design facilitates maintenance and calibration of the pyranometers. Both albedometer kits include a mounting fixture and a glare screen. ALF01 is a levelling fixture that may be combined with AMF03, AMF02 or SRA series albedometers, and helps levelling the instrument. Hukseflux offers a full range of dedicated, ready- Introduction to-use albedometers for measuring albedo. Albedo, also called solar reflectance, is defined as Alternatively, with the AMF03 or AMF02 mounting the ratio of the reflected to the global radiation. fixture in AMF / ALF series, you may choose to The solar albedo depends on the directional construct albedometers from popular Hukseflux distribution of incoming radiation and on surface pyranometers yourself. AMF03, AMF02 and SRA properties at ground level. Albedos of typical series albedometers can be levelled with ALF01 surfaces range from about 4 % for fresh asphalt, levelling fixture. and 15 % for green grass to 90 % for fresh snow. An albedometer is an instrument composed of two pyranometers, the upfacing one measuring global solar radiation, the downfacing one measuring reflected solar radiation. -

![I1470 I Spy (9/15/1965-9/9/1968) [Tv Series]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1375/i1470-i-spy-9-15-1965-9-9-1968-tv-series-561375.webp)

I1470 I Spy (9/15/1965-9/9/1968) [Tv Series]

I1470 I SPY (9/15/1965-9/9/1968) [TV SERIES] Series summary: Spy/adventure series which follows the operations of undercover agents Kelly Robinson (Culp) and Alexander Scott (Cosby). Kelly travels the globe as an international tennis champion, with Scott as his trainer, battling the enemies of the U.S. Happy birthday… everybody (2/26/1968) Credits: director, Earl Bellamy; writers, David Friedkin, Morton Fine Cast: Bill Cosby, Robert Culp, Gene Hackman Summary: Robinson and Scott spot Frank Hunter (Hackman), an escaped mental patient who has promised to track down and kill the retired agent responsible for arresting him after his failure to sabotage an arms shipment being sent to Vietnam. Tatia (11/17/1965) Credits: director, David Friedkin ; writer, Robert Lewin Cast: Bill Cosby, Robert Culp, Laura Devon Summary: Scott becomes involved in the disappearance of three agents bound for Vietnam when a fourth is murdered in his hotel room while a beautiful photographer (Devon) distracts Kelly. War lord (2/1/1967) Credits: director, Alf Cjellin ; writer, Robert Culp Cast: Bill Cosby, Robert Culp, Jean Marsh, Cecil Parker Summary: Set in contemporary Laos. Katherine Faulkner (Marsh), a British aid worker, is kidnapped when the village where she is working is attacked. Her father, the wealthy and politically connected Sir Guy Faulkner, receives a ransom demand from Chuang-Tzu, a Laotian war lord. The charitable organization which sponsored Katherine filmed the attack and has used it to solicit millions in donations, leading Kelly Robinson to suspect the attack may have been a hoax. One of the fundraisers admits to the hoax, but asserts the kidnapping was real. -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

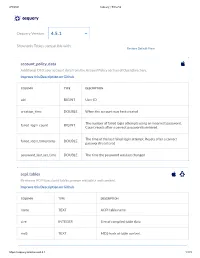

Osquery 4.5.1

2/5/2021 osquery | Schema osquery Osquery Version: 4.5.1 Show only Tables compatible with: Restore Default View account_policy_data Additional OS X user account data from the AccountPolicy section of OpenDirectory. Improve this Description on Github COLUMN TYPE DESCRIPTION uid BIGINT User ID creation_time DOUBLE When the account was rst created The number of failed login attempts using an incorrect password. failed_login_count BIGINT Count resets after a correct password is entered. The time of the last failed login attempt. Resets after a correct failed_login_timestamp DOUBLE password is entered password_last_set_time DOUBLE The time the password was last changed acpi_tables Firmware ACPI functional table common metadata and content. Improve this Description on Github COLUMN TYPE DESCRIPTION name TEXT ACPI table name size INTEGER Size of compiled table data md5 TEXT MD5 hash of table content https://osquery.io/schema/4.5.1 1/173 2/5/2021 osquery | Schema ad_cong OS X Active Directory conguration. Improve this Description on Github COLUMN TYPE DESCRIPTION name TEXT The OS X-specic conguration name domain TEXT Active Directory trust domain option TEXT Canonical name of option value TEXT Variable typed option value alf OS X application layer rewall (ALF) service details. Improve this Description on Github COLUMN TYPE DESCRIPTION allow_signed_enabled INTEGER 1 If allow signed mode is enabled else 0 rewall_unload INTEGER 1 If rewall unloading enabled else 0 1 If the rewall is enabled with exceptions, 2 if the rewall is global_state INTEGER congured to block all incoming connections, else 0 logging_enabled INTEGER 1 If logging mode is enabled else 0 logging_option INTEGER Firewall logging option stealth_enabled INTEGER 1 If stealth mode is enabled else 0 version TEXT Application Layer Firewall version alf_exceptions OS X application layer rewall (ALF) service exceptions. -

The Norman Conquest: the Style and Legacy of All in the Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Boston University Institutional Repository (OpenBU) Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu Theses & Dissertations Boston University Theses & Dissertations 2016 The Norman conquest: the style and legacy of All in the Family https://hdl.handle.net/2144/17119 Boston University BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION Thesis THE NORMAN CONQUEST: THE STYLE AND LEGACY OF ALL IN THE FAMILY by BAILEY FRANCES LIZOTTE B.A., Emerson College, 2013 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts 2016 © 2016 by BAILEY FRANCES LIZOTTE All rights reserved Approved by First Reader ___________________________________________________ Deborah L. Jaramillo, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Film and Television Second Reader ___________________________________________________ Michael Loman Professor of Television DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Jean Lizotte, Nicholas Clark, and Alvin Delpino. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I’m exceedingly thankful for the guidance and patience of my thesis advisor, Dr. Deborah Jaramillo, whose investment and dedication to this project allowed me to explore a topic close to my heart. I am also grateful for the guidance of my second reader, Michael Loman, whose professional experience and insight proved invaluable to my work. Additionally, I am indebted to all of the professors in the Film and Television Studies program who have facilitated my growth as a viewer and a scholar, especially Ray Carney, Charles Warren, Roy Grundmann, and John Bernstein. Thank you to David Kociemba, whose advice and encouragement has been greatly appreciated throughout this entire process. A special thank you to my fellow graduate students, especially Sarah Crane, Dani Franco, Jess Lajoie, Victoria Quamme, and Sophie Summergrad. -

Promote Or Protect? Perspectives on Media Literacy and Media Regulations

Promote Yearbook 2003 Promote or Protect? or Protect? and Media Regulations Media and Literacy Media on Perspectives Perspectives on Media Literacy The International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media and Media Regulations A UNESCO Initiative 1997 Editors: Cecilia von Feilitzen and Göteborg University Nordic Council of Ministers Ulla Carlsson and Ulla Carlsson (eds.) Carlsson Ulla and Feilitzen von Cecilia NORDICOM Göteborg University Box 713 The International Clearinghouse on SE 405 30 GÖTEBORG Children, Youth and Media Tel. +46 31 773 10 00. Fax +46 31 773 46 55 E-mail: [email protected] NORDICOM www.nordicom.gu.se Göteborg University ISSN 1403-4700 Yearbook ISBN 91-89471-23-7 2003 The International The International Clearinghouse Published yearbooks Clearinghouse on Children, on Children, Youth and Media Youth and Media, at One of the most important tasks of The International A UNESCO INITIATIVE 1997 Nordicom Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media is publication of its yearbook. Göteborg University Box 713 Five yearbooks have previously been released. SE 405 30 GÖTEBORG, Sweden In 1997, the Nordic Information Centre for Media and Communication Research (Nordicom), Göteborg Web site: Cecilia von Feilitzen & Ulla Carlsson (eds.): Cecilia von Feilitzen & Ulla Carlsson (eds): http://www.nordicom.gu.se University Sweden, began establishment of the Children, Young People and Media Children in the New Media Landscape. Games, International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and DIRECTOR: Ulla Carlsson Globalisation. Yearbook -

Television Programming for Children: a Report of 'The Children's Televisiontask'fbrce

A ED 183 133 IR* 0Q8 034 AUTHOR GreenWle Susan And Others .TITLE TelevAsion Programming for Children: A Report:of the ChilOenfs Tc4evision Task'FOrce. .'eINSTITUTION. ,PeOral Communications CoMmissicn, 4tsh1ngton, PU 8 DAT h Ot79 NOTE 194p. .4 EDRS PRICE ! ME01/PCOB Plus Póstage. DESCRIPTOR& ^*Broadcast \Industry; nhildens Television; *Compliance (legal): *Educational Policy; Educational Television: *FefUral Regulation: Marketing; Rrograming (BroAdcast); Television Commercials: - Televislon Pel,earch IDENTrFIgRS *Federal Commun,ications,Comm ssion ABSTRACT These two volumes cf a 5-volume.repert cm commerAal* broadcaster complance with thy Federal COmmunications Commission (FCC) 1974 policies on programminil and advertising' to,chilffren provide an overall analysis of ctildrenos television, as well as a detailed analysis of'broadcas, industry compliance. The first volume reviews the social, cognItive, and.economic factors 'that affect t,he, amount, types, and scheduling of childrer0-s programs, and drscuses policy optionz open to 'the FCC with staff recommendationsl The ana14sis of broadcaster compliance dn the second volume il based on a A, series of studies examining the.policy impact on the overalla ount , ofProgramming designed for children 12 years_and under, the afnount sof educatIlertal programming, program SCheduling, and olbvercommerci&lizatibn on children's televisi6nind related advertising issues. The effectiveness of the preent license renewal form as a method of assessing crpliance is also examined. (CMV) 13 , f a. .. , *********************************************1*********************4*** * Repfilductio4S supplied-by EDPS Rre the best that can be made '* . 41% from the original documqnt. , 1 v 0. 1 U.S 'IMPARTMENT OF hEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION e THIS. DOCUMENT HAS 'BEENRePRO. 04 DUCED EXACTIO, AA RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN. -

The Alcotts Through Thirty Years: Letters to Alfred Whitman

The Alcotts through thirty years: Letters to Alfred Whitman The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Schlesinger, Elizabeth Bancroft. 1957. The Alcotts through thirty years: Letters to Alfred Whitman. Harvard Library Bulletin XI (3), Spring 1957: 363-385. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37363765 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Alcotts through Thirty Years: Letters to Alfred Whitman HE correspondence of I ..onisa 1\1ayAlcott and her t,vo sis- ters~ Anna and Ab by 1vlay 1 ,vith Alf red '~'hitman off crs a rern-arkablccxan1plc of u friendship 1asting over a third of a ccn tury, for Alf red, af tcr spending a year in Concord, ,vent to l.1a\vrenceJ l(nnsns, \vhere he remained the greater part of his life. Though Alfred~s letters have disappeared, sixty-five front the A1cotts and John Pratt., Anna's hnsbandt recreate the daily Jife in the Alcott home, providing i11tin1atcglimpses of its 1nen1ber.s.1 The background constantly shifts from Boston to Con cord as the family shuttled f rccly bet,veen these t,,,o places~ Alfred, a moth er less, lonely boy of fifteen, c nrollcd in Franklin B. Sanborn,s private school in 1857. The shy youth bccume a. great favor- ite of the Alcott girls.