Television Programming for Children: a Report of 'The Children's Televisiontask'fbrce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12Th St., S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12th St., S.W. News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 Internet: https://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 DA 18-782 Released: July 27, 2018 MEDIA BUREAU ESTABLISHES PLEADING CYCLE FOR APPLICATIONS FILED FOR THE TRANSFER OF CONTROL AND ASSIGNMENT OF BROADCAST TELEVISION LICENSES FROM RAYCOM MEDIA, INC. TO GRAY TELEVISION, INC., INCLUDING TOP-FOUR SHOWINGS IN TWO MARKETS, AND DESIGNATES PROCEEDING AS PERMIT-BUT-DISCLOSE FOR EX PARTE PURPOSES MB Docket No. 18-230 Petition to Deny Date: August 27, 2018 Opposition Date: September 11, 2018 Reply Date: September 21, 2018 On July 27, 2018, the Federal Communications Commission (Commission) accepted for filing applications seeking consent to the assignment of certain broadcast licenses held by subsidiaries of Raycom Media, Inc. (Raycom) to a subsidiary of Gray Television, Inc. (Gray) (jointly, the Applicants), and to the transfer of control of subsidiaries of Raycom holding broadcast licenses to Gray.1 In the proposed transaction, pursuant to an Agreement and Plan of Merger dated June 23, 2018, Gray would acquire Raycom through a merger of East Future Group, Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gray, into Raycom, with Raycom surviving as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gray. Immediately following consummation of the merger, some of the Raycom licensee subsidiaries would be merged into Gray Television Licensee, LLC (GTL), with GTL as the surviving entity. The jointly filed applications are listed in the Attachment to this Public -

Supremacy WAKR -TV Akron, Ohio WAND Decatur, Ill

ABC -TV's affiliates: 185 going along for a much richer ride KAAL -TV Austin, Minn. KGO -TV San Francisco KOMO -TV Seattle KABC -TV Los Angeles KGTV San Diego KOVR Sacramento, Calif. KAIT -TV Jonesboro, Ark. KGUN -TV Tucson, Ariz. KPAX -TV Missoula, Mont. KAKE -TV Wichita, Kan. KHGI -TV Kearney, Neb. KPLM -TV Palm Springs, Calif. KAPP -TV Yakima, Wash. KHVO Hilo, Hawaii KPOB-TV Popular Bluffs, Mo. KATC Lafayette, La. KIII -TV Corpus Christi, Tex. KPVI Pocatello /Idaho Falls, Idaho KATU Portland, Ore. KIMO Anchorage KQTV St. Joseph, Mo. KATV Little Rock, Ark. KITV Honolulu KRCR -TV Redding, Calif. KBAK -TV Bakersfield, Calif. KIVI -TV Boise, Idaho KRDO Colorado Springs KBMT Beaumont, Tex. KIVV -TV Lead /Deadwood, S.D. KRGV -TV Weslaco, Tex. KBTX -TV Bryan, Tex. KJEO Fresno, Calif. KSAT-TV San Antonio, Tex. KBTV Denver KLTV-TV Tyler, Tex. KSHO -TV Las Vegas KCAU -TV Sioux City, Iowa KMBC -TV Kansas City, Mo. KSNB -TV Superior, Neb. KCBJ -TV Columbia, Mo. KMCC -TV Lubbock, Tex. KSWO -TV Lawton, Okla. KCNA -TV Albion, Neb. KMOM -TV Monahans, Tex. KTBS-TV Shreveport, La. KCRG -TV Cedar Rapids /Waterloo KMSP -TV Minneapolis KTEN Ada, Okla. KDUB Dubuque, Iowa KMTC Springfield, Mo. KTHI -TV Fargo /Grand Forks, N.D. KETV Omaha KNTV San Jose, Calif. KTRE -TV Lufkin, Tex. KEVN -TV Rapid City, S.D. KOAT-TV Albuquerque, N.M. KTRK -TV Houston KEYT Santa Barbara, Calif. KODE -TV Joplin, Mo. KTUL -TV Tulsa, Okla. KEZI -TV Eugene, Ore. KOCO -TV Oklahoma City KTVE -TV El Dorado, Ark. KFBB -TV Great Falls, Mont. -

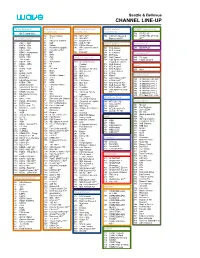

Channel Lineup

Seattle & Bellevue CHANNEL LINEUP TV On Demand* Expanded Content* Expanded Content* Digital Variety* STARZ* (continued) (continued) (continued) (continued) 1 On Demand Menu 716 STARZ HD** 50 Travel Channel 774 MTV HD** 791 Hallmark Movies & 720 STARZ Kids & Family Local Broadcast* 51 TLC 775 VH1 HD** Mysteries HD** HD** 52 Discovery Channel 777 Oxygen HD** 2 CBUT CBC 53 A&E 778 AXS TV HD** Digital Sports* MOVIEPLEX* 3 KWPX ION 54 History 779 HDNet Movies** 4 KOMO ABC 55 National Geographic 782 NBC Sports Network 501 FCS Atlantic 450 MOVIEPLEX 5 KING NBC 56 Comedy Central HD** 502 FCS Central 6 KONG Independent 57 BET 784 FXX HD** 503 FCS Pacific International* 7 KIRO CBS 58 Spike 505 ESPNews 8 KCTS PBS 59 Syfy Digital Favorites* 507 Golf Channel 335 TV Japan 9 TV Listings 60 TBS 508 CBS Sports Network 339 Filipino Channel 10 KSTW CW 62 Nickelodeon 200 American Heroes Expanded Content 11 KZJO JOEtv 63 FX Channel 511 MLB Network Here!* 12 HSN 64 E! 201 Science 513 NFL Network 65 TV Land 13 KCPQ FOX 203 Destination America 514 NFL RedZone 460 Here! 14 QVC 66 Bravo 205 BBC America 515 Tennis Channel 15 KVOS MeTV 67 TCM 206 MTV2 516 ESPNU 17 EVINE Live 68 Weather Channel 207 BET Jams 517 HRTV PayPerView* 18 KCTS Plus 69 TruTV 208 Tr3s 738 Golf Channel HD** 800 IN DEMAND HD PPV 19 Educational Access 70 GSN 209 CMT Music 743 ESPNU HD** 801 IN DEMAND PPV 1 20 KTBW TBN 71 OWN 210 BET Soul 749 NFL Network HD** 802 IN DEMAND PPV 2 21 Seattle Channel 72 Cooking Channel 211 Nick Jr. -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

View Your Release Posted on AD HOC NEWS (View Release) Media Type: News & Information Service Media Location: Germany

View your release posted on AD HOC NEWS (View Release) Media Type: News & Information Service Media Location: Germany AEC Newsroom (View Release) Media Type: Trade Pub Media Location: US AlipesNews (View Release) Media Type: News & Information Service Media Location: Denmark Atlanta Business Chronicle — 389,000 Visitors/Day (View Release) Media Type: Newspaper Media Location: US Austin American-Statesman (Austin, TX) (View Release) Media Type: Newspaper Media Location: US Austin Business Journal — 389,000 Visitors/Day (View Release) Media Type: Newspaper Media Location: US Axleration (View Release) Media Type: Blog Media Location: US Baltimore Business Journal — 389,000 Visitors/Day (View Release) Media Type: Newspaper Media Location: US Birmingham Business Journal — 389,000 Visitors/Day (View Release) Media Type: Newspaper Media Location: US Bizjournals.com, Inc. — 389,000 Visitors/Day (View Release) Media Type: Newspaper Media Location: US Boston Business Journal — 389,000 Visitors/Day (View Release) Media Type: Newspaper Media Location: US Breaking Tech News (View Release) Media Type: Trade Pub Media Location: US Bright Capital Digital Fund (View Release) Media Type: News & Information Service Media Location: Russia Business @ IT Business Net (View Release) Media Type: Trade Pub Media Location: US Business First of Buffalo — 389,000 Visitors/Day (View Release) Media Type: Newspaper Media Location: US Business First of Columbus — 389,000 Visitors/Day (View Release) Media Type: Newspaper Media Location: US Business First of Louisville -

Preliminary Injunction (“Pls.’ Mem.”) at 4

Case 1:10-cv-07415-NRB Document 35 Filed 02/22/11 Page 1 of 59 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------X WPIX, Inc., WNET.ORG, AMERICAN BROADCASTING COMPANIES, INC., DISNEY ENTERPRISES, INC., MEMORANDUM AND CBS BROADCASTING INC, O R D E R CBS STUDIOS INC., THE CW TELEVISION STATIONS INC., 10 Civ. 7415 (NRB) NBC UNIVERSAL, INC., NBC STUDIOS, INC., UNIVERSAL NETWORK TELEVISION,LLC, TELEMUNDO NETWORK GROUP LLC, NBC TELEMUNDO LICENSE COMPANY, OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF BASEBALL, MLB ADVANCED MEDIA, L.P., COX MEDIA GROUP, INC., FISHER BROADCASTING-SEATTLE TV, L.L.C., TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION, FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC., TRIBUNE TELEVISION HOLDINGS, INC., TRIBUNE TELEVISION NORTHWEST, INC., UNIVISION TELEVISION GROUP, INC., THE UNIVISION NETWORK LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, TELEFUTURA NETWORK, WGBJ EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION, THIRTEEN, And PUBLIC BROADCASTING SERVICE, Plaintiffs, - against - ivi, Inc. and Todd Weaver, Defendants. ------------------------------------X NAOMI REICE BUCHWALD UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE Plaintiffs, major copyright owners in television programming, have moved to preliminarily enjoin defendants ivi, 1 Case 1:10-cv-07415-NRB Document 35 Filed 02/22/11 Page 2 of 59 Inc. (“ivi,” with a lowercase “i”) and its chief executive officer, Todd Weaver (“Weaver”), from streaming plaintiffs’ copyrighted television programming over the Internet without their consent. Since plaintiffs have demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits, irreparable harm should -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 103/Thursday, May 28, 2020

32256 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 103 / Thursday, May 28, 2020 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS closes-headquarters-open-window-and- presentation of data or arguments COMMISSION changes-hand-delivery-policy. already reflected in the presenter’s 7. During the time the Commission’s written comments, memoranda, or other 47 CFR Part 1 building is closed to the general public filings in the proceeding, the presenter [MD Docket Nos. 19–105; MD Docket Nos. and until further notice, if more than may provide citations to such data or 20–105; FCC 20–64; FRS 16780] one docket or rulemaking number arguments in his or her prior comments, appears in the caption of a proceeding, memoranda, or other filings (specifying Assessment and Collection of paper filers need not submit two the relevant page and/or paragraph Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2020. additional copies for each additional numbers where such data or arguments docket or rulemaking number; an can be found) in lieu of summarizing AGENCY: Federal Communications original and one copy are sufficient. them in the memorandum. Documents Commission. For detailed instructions for shown or given to Commission staff ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. submitting comments and additional during ex parte meetings are deemed to be written ex parte presentations and SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal information on the rulemaking process, must be filed consistent with section Communications Commission see the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In (Commission) seeks comment on several section of this document. proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) proposals that will impact FY 2020 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of the Commission’s rules or for which regulatory fees. -

KNXT Dereservation Petition

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Amendment of Section 73.622(b) ) MB Docket No. ____ DTV Table of Allotments ) RM No. ____ (Visalia, California) ) To: Office of the Secretary Attn: Chief Video Division, Media Bureau JOINT PETITION FOR RULEMAKING AND REQUEST FOR WAIVER DIOCESE OF FRESNO EDUCATION CORP. and VENTURA TV VIDEO AND APPLIANCE CENTER, INC. Michelle A. McClure, Esq. Kathleen Victory, Esq. Keenan P. Adamchak, Esq. Fletcher, Heald & Hildreth, PLC 1300 N. 17th Street, Suite 1100 Arlington, VA 22209 Tel: (703) 812-0400 Fax: (703) 812-0486 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Petitioners Date: August 9, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... ii I. “COMPELLING CIRCUMSTANCES” JUSTIFY DERESERVATION OF CHANNELS *50/*22, VISALIA, CALIFORNIA ........................................................................................... 2 A. Operation of KNXT as an NCE Television Station is not Financially Viable ............. 3 B. Operation of KNXT as a Commercial Television Station would not have a Negative Impact on the Fresno-Visalia Market ..................................................................................... 7 C. The Public Interest Benefits of Operating KNXT as a Commercial Station Outweigh the need for 2 NCE Television Stations in the Fresno Market ............................................... 8 II. IT IS IN -

Digital and Analog Television Interference with VHF Systems This Product Operates Between 72-87 MHZ and 170-234 Mhz

Digital and Analog Television interference with VHF systems This product operates between 72-87 MHZ and 170-234 MHz TV CH Freq MHz VHF Frequency Channel None ----- 72.300 MHz BB None ----- 72.500 MHz CC None ----- 72.700 MHz DD None ----- 72.900 MHz EE None ----- 75.500 MHz FF None ----- 75.700 MHz GG None ----- 75.900 MHz HH None ----- 81.350 MHz MB1 6 82-88 83.880 MHz MB2 6 82-88 85.275 MHz MB3 6 82-88 87.375 MHz MB4 None ----- 170.245 MHz G1 None ----- 171.905 MHz A None ----- 173.800 MHz E4 None ----- 174.100 MHz E5 7 174-180 174.500 MHz E6 7 174-180 175.000 MHz E3 7 174-180 175.550 MHz CE6 7 174-180 176.400 MHz CE7 7 174-180 176.900 MHz A14 8 180-186 183.570 MHz CE9 8 180-186 185.150 MHz B 8 180-186 185.250 MHz CE1 9 186-192 191.300 MHz H 10 192-198 195.250 MHz CE2 10 192-198 197.150 MHz N 11 198-204 202.100 MHz A1 11 198-204 203.250 MHz CE3 11 198-204 203.400 MHz F 12 204-210 206.350 MHz P 12 204-210 209.150 MHz D 13 210-216 212.100 MHz R 13 210-216 215.200 MHz E None ----- 219.200 MHz K None ----- 226.225 MHz M None ----- 231.650 MHz J2 None ----- 232.800 MHz CE5 None ----- 234.100 MHz J4 169.445, 170.245, 171.905, None ----- AT2 171.045 MHz 170.245, 171.905, 172.650, None ----- AT 170.850 MHz 182.800, 184.450, 185.150, 8 180-186 A8 183.300 MHz 182.800, 184.450, 185.150, 8 180-186 AE8 183.570 MHz 188.800, 190.450, 191.300, 9 186-192 A9 189.300 MHz 194.800, 196.450, 197.150, 10 192-198 A10 195.250 MHz Potential problems with local interference As of 10/11/04 Station Types, TV = Full Service TV, DT = Digital TV, CA = Class A, TX = Low Power TV and Translator, TB = Booster TV, TS = Auxiliary Back Up Call State CITY TV Ch. -

Ed Phelps Logs His 1,000 DTV Station Using Just Himself and His DTV Box. No Autologger Needed

The Magazine for TV and FM DXers October 2020 The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association Being in the right place at just the right time… WKMJ RF 34 Ed Phelps logs his 1,000th DTV Station using just himself and his DTV Box. No autologger needed. THE VHF-UHF DIGEST The Worldwide TV-FM DX Association Serving the TV, FM, 30-50mhz Utility and Weather Radio DXer since 1968 THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, SAUL CHERNOS, KEITH MCGINNIS, JAMES THOMAS AND MIKE BUGAJ Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org/info Webmaster: Tim McVey Forum Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Creative Director: Saul Chernos Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, John Zondlo and Mike Bugaj The WTFDA Board of Directors Doug Smith Saul Chernos James Thomas Keith McGinnis Mike Bugaj [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Renewals by mail: Send to WTFDA, P.O. Box 501, Somersville, CT 06072. Check or MO for $10 payable to WTFDA. Renewals by Paypal: Send your dues ($10USD) from the Paypal website to [email protected] or go to https://www.paypal.me/WTFDA and type 10.00 or 20.00 for two years in the box. Our WTFDA.org website webmaster is Tim McVey, [email protected]. -

KNXT Channel 2 Press Releases 0232

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c83t9gg6 No online items Finding Aid of KNXT Channel 2 press releases 0232 Finding aid prepared by Katie Richardson and Boriana Boyanova The processing of this collection and the creation of this finding aid was funded by the generous support of the Council on Library and Information Resources. 1st edition USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California, 90089-0189 213-740-5900 [email protected] June 2010 Finding Aid of KNXT Channel 2 0232 1 press releases 0232 Title: KNXT Channel 2 press releases Collection number: 0232 Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 3.0 Linear feet3 boxes Date (inclusive): 1961-1962 Abstract: The collection includes press releases from 1961 to 1962. creator: CBS Radio Network. creator: KNX (Radio station : Los Angeles, Calif.). creator: KNXT (Television station : Los Angeles, Calif.). Preferred Citation [Identification of item], KNXT Channel 2 press releases, Collection no. 0232, Regional History Collections, Special Collections, USC Libraries, University of Southern California. Conditions Governing Use The collection contains published articles; researchers are reminded of the copyright restrictions imposed by publishers on reusing their articles and parts of books. It is the responsibility of researchers to acquire permission from publishers when reusing such materials. The copyright to unpublished materials belongs to the heirs of the writers. Permission to publish, quote, or reproduce must be secured from the repository and the copyright holder. Conditions Governing Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE. Advance notice required for access. Consult finding aid for additional information. -

KLRU-TV, Analog Channel 18, Digital Channel 22, PBS CEO

GENERAL MANAGER KITU, Analog Channel 34, Digital Channel 33, IND Amy Villarreal Licensee: Community Educational Television, Inc. NEWS DIRECTOR 11221 Interstate 10, Orange, TX 77630. TEL: (409) 745-3434. Tim Gardner FAX: (409) 745-4752. www.communityedtv.org KLRU-TV, Analog Channel 18, Digital Channel 22, PBS BROWNSVILLE, TX, MARKET Licensee: Capital of Texas Public Telecomm. see Harlingen - Weslaco - Brownsville - McAllen, TX, 2504 Whitis St., Biog. 5, Austin, TX 78712. Market TEL: (512) 471-4811. FAX: (512) 475-9090. www.klru.org CEO & PRESIDENT BRYAN, TX, MARKET Bill Slotesbery see Waco -Temple - Bryan, TX, Market KNVA, Analog Channel 54, Digital Channel 49, CW CORPUS CHRISTI, TX, MARKET Licensee: 54 Broadcasting Inc. Owners: Dian Levy, 25%; Frank (DMA 129) Goldberg, 25%; Mark Goldberg, 25%; and Richard Goldberg 25%. KEDT, Analog Channel 16, Digital Channel 32, PBS 908 W. Martin Luther King Blvd, Austin, TX 78768. Licensee:South Texas Public Broadcasting System. TEL: (512) 478-5400. FAX: (512) 476-1520. 4455 S. Padre Island Dr., Ste. 38, Corpus Christi, TX 78411. www.thecwaustin.com TEL: (361) 855-2213. FAX: (361) 855-3877. www.kedt.org GENERAL MANAGER PRESIDENT & GENERAL MANAGER Carlos Fernandez Don Dunlap KTBC, Analog Channel 7, Digital Channel 56, FOX OPERATIONS DIRECTOR & CHIEF OF ENGINEERING Licensee: KTBC License, Inc. Cody Blount Group Owner: Fox Television Stations, Inc. KIII, Analog Channel 3, Digital Channel 8, ABC 119 E. 10th St., Austin, TX 78701. TEL: (512) 476-7777. Licensee: Channel 3 of Corpus Christi, Inc. FAX: (512) 495-7001. email: [email protected] Group Owner: McKinnon Broadcasting Co. www.fox7.com 5002 S.