Proposed Ilitha Housing Development Project, Ilitha, Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality, Eastern Cape Province

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRAFT IDP Attached

BUFFALO CITY METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY 2019/20 DRAFT INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN REVIEW “A City Hard at Work” Third (3rd) Review of the 2016-2021 Integrated Development Plan as prescribed by Section 34 of the Local Government Municipal Systems Act (2000), Act 32 of 2000 Buffalocity Metropolitan Municipality | Draft IDP Revision 2019/2020 _________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Content GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS 3 MAYOR’S FOREWORD 5 OVERVIEW BY THE CITY MANAGER 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 SECTION A INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 15 SECTION B SITUATION ANALYSIS PER MGDS PILLAR 35 SECTION C SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 217 SECTION D OBJECTIVES, STRATEGIES, INDICATORS, 240 TARGETS AND PROJECTS SECTION E BUDGET, PROGRAMMES AND PROJECTS 269 SECTION F FINANCIAL PLAN 301 ANNEXURES ANNEXURE A OPERATIONAL PLAN 319 ANNEXURE B FRAMEWORK FOR PERFORMANCE 333 MANAGEMENT SYSTEM ANNEXURE C LIST OF SECTOR PLANS 334 ANNEXURE D IDP/BUDGET PROCESS PLAN FOLLOWED 337 ANNEXURE E WARD ISSUES/PRIORITIES RAISED 2018 360 ANNEXURE F PROJECTS/PROGRAMMES BY SECTOR 384 DEPARTMENTS 2 Buffalocity Metropolitan Municipality | Draft IDP Revision 2019/2020 _________________________________________________________________________________ Glossary of Abbreviations A.B.E.T. Adult Basic Education Training H.D.I Human Development Index A.D.M. Amathole District Municipality H.D.Is Historically Disadvantaged Individuals AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome H.R. Human Resources A.N.C₁ African National Congress H.I.V Human Immuno-deficiency Virus A.N.C₂ Antenatal Care I.C.D.L International Computer Drivers License A.R.T. Anti-Retroviral Therapy I.C.Z.M.P. Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan A.S.G.I.S.A Accelerated Shared Growth Initiative of South Africa I.D.C. -

Case Study of King William's Town

Water Supply Services Model: Case Study of King William's Town Report to the Water Research Commission by Palmer Development Group WRC Report No KV110/98 Disclaimer This report emanates from a project financed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and is approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC or the members of the project steering committee, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Vry waring Hierdie verslag spruit voort uit 'n navorsingsprojek wat dour die Waternavorsingskommissie (WNK) gefinansier is en goedgekeur is vir publikasie. Gocdkcuring beteken nie noodwendig dat die inhoud die sicning en bclcid van die WNK of die lede van die projek-loodskoinitee weerspieel nie, of dat melding van handelsname of -ware deur die WNK vir gebruik goedgekeur of aanbeveel word nie. WATER SUPPLY SERVICES MODEL : CASE STUDY OF KING WILLIAM'S TOWN Report on application of the WSSM to the King William's Town TLC PALMER DEVELOPMENT GROUP WRC Report No KV110/98 ISBN 1 86845 407 X ISBN SET 1 86845 408 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to extend our thanks to the officials and councillors of the King William's Town TLC for giving us access to the information necessary to conduct this study. We would in particular like to thank the Town Engineer Chris Hetem, the Treasurer Gideon Thiart, Hans Schluter of the Planning Department and Trevor Belser of the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry for their time and support during the course of the study. -

Draft Built Environment Performance Plan 2017/2018

DRAFT BUILT ENVIRONMENT PERFORMANCE PLAN 2017/2018 Draft 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………............................................................................6 PROFILE OF THE BUFFALO CITY METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY ............................................................................... 6 SECTION A ........................................................................................................................................................................ 9 A.1. BEPP IN RELATION TO OTHER STATUTORY PLANS .............................................................................................. 10 A.1.1. BCMM Documents: .......................................................................................................................................... 11 A.1.2. National and Provincial Documents: .............................................................................................................. 11 A.1.3. Aligning the BEPP with IDP, MGDS, BCMM SDF and Budget ................................................................. 12 A.1.4. Confirmation of BEPP Adoption by Council ..................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. SECTION B : SPATIAL PLANNING &PROJECT PRIORITISATION ...................................................................................... 14 B.1. SPATIAL TARGETING ............................................................................................................................... 14 (a) The National Development Plan -

BUF Buffalo City Draft BEPP 2017-18

DRAFT BUILT ENVIRONMENT PERFORMANCE PLAN 2017/2018 Draft 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 PROFILE OF THE BUFFALO CITY METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY ..................................................................................... 5 SECTION A ........................................................................................................................................................................ 8 A.1. BEPP IN RELATION TO OTHER STATUTORY PLANS ................................................................................................ 9 A.1.1. BCMM Documents: ........................................................................................................................................ 9 A.1.2. National and Provincial Documents: .......................................................................................................... 10 A.1.3. Aligning the BEPP with IDP, MGDS, BCMM SDF and Budget ............................................................. 10 A.1.4. Confirmation of BEPP Adoption by Council .............................................................................................. 12 SECTION B : SPATIAL PLANNING &PROJECT PRIORITISATION ...................................................................................... 13 B.1. SPATIAL TARGETING .............................................................................................................................. -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA Regulation Gazette No. 10177 Regulasiekoerant March Vol. 657 13 2020 No. 43086 Maart PART 1 OF 2 ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 43086 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 43086 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 13 MARCH 2020 IMPORTANT NOTICE OF OFFICE RELOCATION Private Bag X85, PRETORIA, 0001 149 Bosman Street, PRETORIA Tel: 012 748 6197, Website: www.gpwonline.co.za URGENT NOTICE TO OUR VALUED CUSTOMERS: PUBLICATIONS OFFICE’S RELOCATION HAS BEEN TEMPORARILY SUSPENDED. Please be advised that the GPW Publications office will no longer move to 88 Visagie Street as indicated in the previous notices. The move has been suspended due to the fact that the new building in 88 Visagie Street is not ready for occupation yet. We will later on issue another notice informing you of the new date of relocation. We are doing everything possible to ensure that our service to you is not disrupted. As things stand, we will continue providing you with our normal service from the current location at 196 Paul Kruger Street, Masada building. Customers who seek further information and or have any questions or concerns are free to contact us through telephone 012 748 6066 or email Ms Maureen Toka at [email protected] or cell phone at 082 859 4910. Please note that you will still be able to download gazettes free of charge from our website www.gpwonline.co.za. -

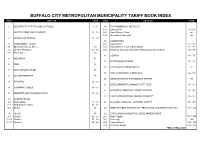

Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality Tariff Book Index Item Service Page Item Service Page

BUFFALO CITY METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY TARIFF BOOK INDEX ITEM SERVICE PAGE ITEM SERVICE PAGE 1 ELECTRICITY TARIFFS AND CHARGES 1 - 11 14 ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES 14.1 East London 63 - 65 2 WATER TARIFF AND CHARGES 11 - 20 14.2 King William's Town 66 14.3 Atmospheric Emission 66 3 SEWERAGE TARIFFS 21 - 29 15 CEMETERIES 4 ASSESSMENT RATES 15.1 East London 67 - 70 4.1 Municipal Property Rates 30 15.2 King William's Town and Breidbach 71 - 72 4.2 Uniform Flat Rates 31 - 33 15.3 Ginsberg, Dimbaza, Zwelitsha, Phakamisa & Ilitha & Bisho 72 - 73 4.3 Rates Other 33 16 LIBRARY 74 - 75 5 AQUARIUM 34 17 WASTE MANAGEMENT 76 - 80 6 ZOO 34 18 CITY HEALTH DEPARTMENT 81 7 BOAT REGISTRATION 35 19 FIRE & EMERGENCY SERVICES 82 - 84 8 NATURE RESERVE 35 20 ADMINISTRATION CHARGE-OUT TARIFFS 85 9 BEACHES 36 - 37 21 DEVELOPMENT PLANNING TARIFF FEES 85 - 91 10 SWIMMING POOLS 38 - 43 22 SCIENTIFIC SERVICES TARIFF CHARGES 92 - 95 11 RESORTS AND CARAVAN PARKS 44 - 46 23 EAST LONDON FRESH PRODUCE MARKET 96 - 97 12 SPORTSFIELDS 12.1 East London 47 - 50 24 ALL DIRECTORATES - GENERAL TARIFFS 98 - 100 12.2 King William's Town 41 - 52 12.3 Bhisho 52 25 FEES PAYABLE IN TERMS OF THE ACCESS TO INFORMATION ACT 101 - 102 13 HALLS 54 26 EAST LONDON INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ZONE 13.1 Group 1 55 - 57 26.1 Water Supply 103 - 105 13.1.4 Group 2 57 - 58 26.2 Sewerage 105 13.1.7 Group 3 59 - 62 26.3 Trade Effluent 106 - 108 26.4 Electricity Supply 108 - 109 FINAL 30 May 2018 2017/18 2017/18 2017/18 2018/19 2018/19 2018/19 Total VAT Total Total VAT Total Item Code Service R/cents R/cents R/cents R/cents R/cents R/cents Excl VAT 14% VAT Incl. -

A Situation Analysis of Water Quality in the Catchment of the Buffalo River, Eastern Cape, with Special Emphasis on the Impacts

A SITUATION ANALYSIS OF WATER QUALITY IN THE CATCHMENT OF THE BUFFALO RIVER, EASTERN CAPE, WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON THE IMPACTS OF LOW COST, HIGH-DENSITY URBAN DEVELOPMENT ON WATER QUALITY VOLUME 2 (APPENDICES) FINAL REPORT to the Water Research Commission by Mrs C.E. van Ginkel Dr J. O'Keeffe Prof D.A.Hughes Dr J.R. Herald Institute Tor Water Research, Rhodes University and Dr P.J. Ashton Environmentek, CSIR WRC REPORT NO. 40S/2/96 ISBN NO. 1 86845 287 5 ISBN SET NO. 1 86845 288 3 Water Research. Commission Buffalo River Project EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Introduction and aims of the project The Buffalo River provides water and a conduit for effluent disposal in one of the most populous areas on the East coast of southern Africa. The catchment supports a rapidly-growing population of 311 000 people, in which King William's Town, Zwelitsha, Mdantsane and East London are the mam towns, and they are all supplied with water from the river. The management of the river is complicated by the political division of the catchment between Ciskei and South Africa (figure 1.1), but a joint agreement makes provision for the formation of a Permanent Water Commission for coordinating the management of the river's resources. The river rises in the Amatole Mountains and flows South-East for 125 km to the sea at East London (figure 1.1). It can be divided into three reaches: The upper reaches to King William's Town, comprising the mountain stream in montane forest down to Maden Dam, and the foothill zone flowing through agricultural land downstream of Rooikrans Dam; the middle reaches, comprising the urban/industrial complex of King William's Town/Zwelitsha to Laing Dam, and an area of agricultural land downstream of Laing; and the lower reaches downstream of Bridle Drift Dam, comprising coastal forest and the estuary, which forms East London's harbour. -

Final Basic Assessment Report for Mount Coke Quarry, Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality

MOUNT COKE QUARRY FINAL BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR MOUNT COKE QUARRY, BUFFALO CITY METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY Report prepared for K2019436499 SOUTH AFRICA (PTY) LTD Report prepared by No.2 Deer Park Lane ; Deer Park Estate ; Port Elizabeth ; 6070 PO Box 16501 ; Emerald Hill ; 6011 Telephone : +27 (0) 41 379 1899 Mobile : +27(0) 82 653 2568 Facsimile : +27 351 e-mail : [email protected] February 2020 DRAFT BA and EMPr Report Page 1 of 192 MOUNT COKE QUARRY Table of Contents List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ 6 Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................. 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 8 1. IMPORTANT NOTICE .................................................................................................... 12 2. OBJECTIVE OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROCESS .......... 13 PART A ............................................................................................................................... 14 SCOPE OF ASSESSMENT AND BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT ................................... 14 1) Contact Person and correspondence address .......................................................... 14 i) Details ....................................................................................................................... 14 ii) Expertise of the EAP. .............................................................................................. -

King Williams Town Education District I Z V IE I Tylden R MIDDLE XOLOBE JS JOJWENI 4 NTSELA Intsika Yethu Local Municipality ZWELIVUMILE SS

1 4 2 3 1 4 2 3 G 1 8 U 1 8 G U T LA O LU B 3 U O UPPER NQOLOSA JS ESIKOLWENI 3 NY Y 11 22 I NDLOVUKAZI JP TOBOYI K NQOLOSA W U MDANTSANE 22 33 IT B - A KE KWANANGCANGCAZELA 2 0 IR N 2 0 King Williams Town Education District I Z V IE I Tylden R MIDDLE XOLOBE JS JOJWENI 4 NTSELA Intsika Yethu Local Municipality ZWELIVUMILE SS R ESIXHOTYENI N E H MZAMOMHLE JP FAIRVIEW JP I G O O 1 6 V X 1 6 I W M H NOMZAMO SP CENU R I A O I T KWAJIM E S S R H A T K E - U I T R V I I E I W BABA ROAD R V NOLUSAPHO SP T NQOLOSA JS I A R Z I A MBHONGISENI O L E BORDERLINE/KOMKHULU L K P A - S BENGU JS NI O P I N T I W O UD OM L L R MPIKWANA JS A O UB H K G E A Q SI YA N JOJWENI 3 W S MKHANYENI KWAKHOZA SAJINI JS A X AN MADAM E AL E NK 11 55 B S O A L N R 11 66 E Lukanji Local Municipality O D A IN Whittlesea E 1 3 IN I 1 3 X NCIS V I R E 11 99 D E I IN N K K I - KWA JACK 2 T S U G I T CAMPBELL MNYHILA JP S C Z C O N O E I B M O A KWA JACK 1 A 11 33 O R S L G O G O MZAMOMHLEJOJO JS C L M I M B B A O U A A G LU L N N A LA 11 77 U E XOLOBA O K U 1 8 Q G NKALWENI BENGU M O AK 1 8 A R O P MTW W O X 22 00 O U T L - BLY NGCONGOLO JP K A E G N 11 77 IR R I O A V O Y I T LAMTHOLE E - KENSINGTON T R K E CULU E IR SONKOSI JS NG B I V E IE Nqamakwe Bacela R G N KHUZE NKQUBELA JS CENYU NGXALAWA KANYISA SP MATOLWENI TEMBENI JS MCHEWULA 2 A B MCHEWULA 1 A Mbulukweza Clinic C BE A E N FUBU BE-H MBULUKWEZA HE A K A GCIBHALA MAGWATYUZENI D A N B 11 33 H A E 1 5 C B 1 5 CABA JS LUXOMO E A DUBUKAZI - CABA COMPREHENSIVE NDEMA SS H N E A I B K T DUMEZWENI J S S KWAMFULA 1 A N A -

IN the HIGH COURT of SOUTH AFRICA BHISHO Case No. CA&R

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA BHISHO Case No. CA&R/2008 In the matter between: VINTA WORKMAN GQIRANA APPELLANT AND THE STATE RESPONDENT APPEAL JUDGMENT _____________________________________________________________ GREENLAND AJ: [1] This is an appeal in respect of convictions and sentences handed down by the High Court, Bisho. [2] Conviction The appellant, and four (4) others, were convicted of ± Count 1) Murder, by shooting, of adult male Alfred Nzimeni Makasi, on 1st April 2002 at Ilitha Township, Zwelitsha. Count 2) Attempted murder, by shooting and wounding, of one Nolulamile Nonkosi Makasi, on the same date and at the same place. Count 3) Robbery with aggravating circumstances of adult male Alfred Nzimeni Makasi of the sum of R38 000,00 at the same time and place. Count 4) Robbery with aggravating circumstances of adult male Alfred Nzimeni Makasi of a motor vehicle at the same time and place. Of the five accused only the appellant, who appeared as Accused 1 at the trial in the court, a quo, has appealed. [3] Incident All the charges arise on account of an incident which occurred at Ilitha Township, Zwelitsha on the evening of 01 April 2002. Four of the accused confronted the victims in their home. The deceased was shot several times and according to the post-mortem report died of ªbullet wounds to the chestº. His wife, complainant in Count 2, also sustained gunshot injuries but fortunately survived. In Counts 3 and 4 the deceased was relieved of the money and a vehicle at gunpoint. It is common cause that the actions of the perpetrators constitute the charges alleged. -

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Eastern Cape

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Eastern Cape Permit Primary Name Address Number 202103960 Fonteine Park Apteek 115 Da Gama Rd, Ferreira Town, Jeffreys Bay Sarah Baartman DM Eastern Cape 202103949 Mqhele Clinic Mpakama, Mqhele Location Elliotdale Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103754 Masincedane Clinic Lukhanyisweni Location Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103840 ISUZU STRUANWAY OCCUPATIONAL N Mandela Bay MM CLINIC Eastern Cape 202103753 Glenmore Clinic Glenmore Clinic Glenmore Location Peddie Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103725 Pricesdale Clinic Mbekweni Village Whittlesea C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103724 Lubisi Clinic Po Southeville A/A Lubisi C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103721 Eureka Clinic 1228 Angelier Street 9744 Joe Gqabi DM Eastern Cape 202103586 Bengu Clinic Bengu Lady Frere (Emalahleni) C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103588 ISUZU PENSIONERS KEMPSTON ROAD N Mandela Bay MM Eastern Cape 202103584 Mhlanga Clinic Mlhaya Cliwe St Augustine Jss C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103658 Westering Medicross 541 Cape Road, Linton Grange, Port Elizabeth N Mandela Bay MM Eastern Cape Updated: 30/06/2021 202103581 Tsengiwe Clinic Next To Tsengiwe J.P.S C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103571 Askeaton Clinic Next To B.B. Mdledle J.S.School Askeaton C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103433 Qitsi Clinic Mdibaniso Aa, Qitsi Cofimvaba C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103227 Punzana Clinic Tildin Lp School Tildin Location Peddie Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103186 Nkanga Clinic Nkanga Clinic Nkanga Aa Libode O Tambo DM Eastern Cape 202103214 Lotana Clinic Next To Lotana Clinic Lotana -

East London Education District

MKHONJANI NYABAVU MAZOTSHWENI XHOBANI QOBOQOBO SOMANA NKUKWANE GODIDI KWATHYAU NXAXHA KWANOBUSWANA GOJELA 2 4 MMANGWENI A GQUNQE QORA1 6 11 55 HECKEL KWABINASE EBHITYOLO 2 4 QIN GOBE MANUBE MANUBI 1 6 K LU MQAMBILE 11 00 SIZI LUSIZI GQUNQE Mbhashe Local Municipality ENGQANDA W S ANE A I TSIM K H A MANTETYENI N DIKHOHLONG N L WARTBURG I U LUSIZI GCINA O SEMENI NXAXHO B G O 1 4 L C GQUNQE Q N GCINA LUKHOLWENI 1 4 L HLANGANI GOBE NTILINI W A Qina Clinic G 44 O KWAMANQULU A T N R L RAWINI W I A Mgwali Clinic GOBE Z POTHLO W G 2 3 NTSHONGWENI E R Springs Clinic 2 3 NXQXHO M HLANGANI N E MGWALI GQUNQE I N V G G GCINA E I R GOBE NXAXHO B O EMAHLUBINI MAFUSINI SIGANGENI O E R O KOBODI INDUSTRIAL VIKA LE E T D CEBE CHEBE L T - LUSIZI MATEYISI GCINA E S I GQUNQE O K NCIBA GOBE I E MPHUMLANI DYOSINI KOBODI THEMBANI D I O I GODIDI R I S I T V A NJINGINI E I ER KOBODI A L 2 2 MANZAMA A R 2 2 NTINDE G I TOL E M V NI NDUVENI N E NXAXHO A N LA NDUBUNGE LUSIZI R N G Y Y X MATSHONA I LUSIZI A A O S S X T N KEI BRIDGE 66 GCINA GCINA I W A NTSANGANE H 11 R A A A Macibe Clinic ZIBUNU GQUNQE GCINA E R N S L IV ENTLEKISENI K M DLEPHU A E H KWA NGWANE COLUMBA MISSION O R U I U I MACIBE LUSIZI LU N E L B Q M SI GQ S A K Z U T I I I NQ O W U KOBODI B MACIBE E G O L MAZZEPA BAY T S G D A E M B C CI M W I Q E A B CHEBE M I KWATHALA MACIBE SINTSANA A N E U B O U NKENTE B O N N L X O N E B C E I K A K 7 Q G G MNYAMENI 7 Ngqusi Clinic U MNYAMA M U X Q KOBODI D 99 R A B MACIBE O O GQUNQE O O B U EDRAYINI BO KOMKHULU MB D L I O AZELA A O S DLEPHU B T N BUSY VILLAGE N