A Few Virginia Vintners Are Hell-Bent on Making the South's First Truly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Growth 2000S Does the Market Have It All Wrong?

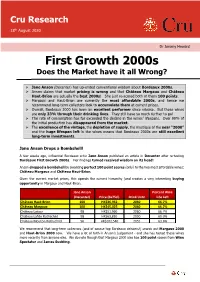

Cru Research 18th August 2020 Dr Jeremy Howard First Growth 2000s Does the Market have it all Wrong? ➢ Jane Anson (Decenter) has up-ended conventional wisdom about Bordeaux 2000s. ➢ Anson claims that market pricing is wrong and that Château Margaux and Château Haut-Brion are actually the best 2000s! She just re-scored both of them 100 points. ➢ Margaux and Haut-Brion are currently the most affordable 2000s, and hence we recommend long-term collectors look to accumulate them at current prices. ➢ Overall, Bordeaux 2000 has been an excellent performer since release. But these wines are only 33% through their drinking lives. They still have so much further to go! ➢ The rate of consumption has far exceeded the decline in the wines’ lifespans. Over 99% of the initial production has disappeared from the market. ➢ The excellence of the vintage, the depletion of supply, the mystique of the year “2000” and the huge lifespan left in the wines means that Bordeaux 2000s are still excellent long-term investments. Jane Anson Drops a Bombshell! A few weeks ago, influential Bordeaux critic Jane Anson published an article in Decanter after re-tasting Bordeaux First Growth 2000s. Her findings turned received wisdom on its head! Anson dropped a bombshell by awarding perfect 100 point scores (only) to the two most affordable wines: Château Margaux and Château Haut-Brion. Given the current market prices, this upends the current hierarchy (and creates a very interesting buying opportunity in Margaux and Haut-Brion. Jane Anson Percent Wine (Decanter) Price (6x75cl) Drink Until Life Left Château Haut-Brion 100 HK$36,952 2060 66.7% Château Margaux 100 HK$45,025 2060 66.7% Château Latour 98 HK$51,960 2060 66.7% Château Lafite Rothschild 98 HK$63,810 2050 60.0% Château Mouton Rothschild 96 HK$102,540 2055 63.6% We recommend that long-term collectors (and of course top Bordeaux drinkers!) search out Margaux 2000 and Haut-Brion 2000 now. -

First Growth SHOWDOWN

Roberson Wine presents: First Growth SHOWDOWN Thursday March 5th 2009 fIrst growth showdown The Vintages “1995 is an excellent to outstanding1995 vintage of consistently top-notch red wines.” Robert Parker The early 1990s were a dark period for the Bordelais, and ‘95 was the first high quality vintage since 1990. ‘91 through to ‘94 was a procession of poor to average vintages that yielded very few excellent wines, but a superb (and consistent) start to ‘95 led into the driest summer for 20 years and subsequently the first serious En Primeur campaign since the start of the decade. The rain that came in mid-September soon passed, and the top properties from the Haut-Medoc allowed more time for their Cabernet to fully ripen before picking. Tonight we will taste four of the second wines from the ‘95 vintage, all of which should be hitting their stride about now with more room left for development in the future. “T his is one of the most perfect 1985vintages, both for drinking now and for keeping. It is certainly my favourite vintage of this splendid decade, typifying claret at its best.” Michael Broadbent After the disastrous 1984 vintage and one of the coldest winters on record, the Chateaux owners of Bordeaux were apprehensive about the ‘85 vintage. What ensued was a long and remarkably consistent (albeit dotted with bouts of rain) growing season that culminated in absolutely perfect harvest conditions and beautifully ripe fruit. The properties that harvested latest of all (including the first growths) reaped the benefits and produced supple and silky wines that have aged beautifully. -

2010 58% Merlot & 42% Cabernet Franc Columbia Valley

2010 58% Merlot & 42% Cabernet Franc Columbia Valley This vintage was sourced from the acclaimed Conner Lee Vineyard with 5% from Champoux Vineyard. Caleb has worked with Conner Lee’s phenomenal merlot and cabernet franc since its first harvest in 1994. Conner Lee is a cool site in a warm, sunny region of Washington state. In the eastern Washington desert, the hot summer ripens the fruit, while the diurnal temperatures keep the acids high and the pH low. Buty has bottled its own blend of merlot & cabernet franc since 2000, our inaugural vintage. Like the yields of Bordeaux First Growth harvests, in a normal year at Conner Lee we grow 30 HL per hectare, equal to two tons per acre or 3.5 pounds per plant. But 2010 was the coolest vintage in thirty years, so we further cut yields in the summer to 20 HL per hectare to ensure fully ripe character for our wine. We harvested our merlot by hand on October 7. Cabernet franc we harvested on October 22 at potential alcohols of 14.3%. We hand-sorted and destemmed with gravity transfer to tank, which allowed us to preserve the fruit's abundant aromatics. We aerated during fermentation in wood tanks for two weeks and selected only free-run wine to blend. Aged 14 months in Taransaud and Bel Air French Château barrels, half of which were new, the wines rested unracked until bottling in December 2011. This is one of Washington's fabulous wines that though very pretty in its youth, will also be very long lived. -

Sauvignon Blanc: Past and Present by Nancy Sweet, Foundation Plant Services

Foundation Plant Services FPS Grape Program Newsletter October 2010 Sauvignon blanc: Past and Present by Nancy Sweet, Foundation Plant Services THE BROAD APPEAL OF T HE SAUVIGNON VARIE T Y is demonstrated by its woldwide popularity. Sauvignon blanc is tenth on the list of total acreage of wine grapes planted worldwide, just ahead of Pinot noir. France is first in total acres plant- is arguably the most highly regarded red wine grape, ed, followed in order by New Zealand, South Africa, Chile, Cabernet Sauvignon. Australia and the United States (primarily California). Boursiquot, 2010. The success of Sauvignon blanc follow- CULTURAL TRAITS ing migration from France, the variety’s country of origin, Jean-Michel Boursiqot, well-known ampelographer and was brought to life at a May 2010 seminar Variety Focus: viticulturalist with the Institut Français de la Vigne et du Sauvignon blanc held at the University of California, Davis. Vin (IFV) and Montpellier SupAgro (the University at Videotaped presentations from this seminar can be viewed Montpellier, France), spoke at the Variety Focus: Sau- at UC Integrated Viticulture Online http://iv.ucdavis.edu vignon blanc seminar about ‘Sauvignon and the French under ‘Videotaped Seminars and Events.’ clonal development program.’ After discussing the his- torical context of the variety, he described its viticultural HISTORICAL BACKGROUND characteristics and wine styles in France. As is common with many of the ancient grape varieties, Sauvignon blanc is known for its small to medium, dense the precise origin of Sauvignon blanc is not known. The clusters with short peduncles, that make it appear as if variety appears to be indigenous to either central France the cluster is attached directly to the shoot. -

Château Graville-Lacoste

CHÂTEAU DUCASSE CHÂTEAU ROUMIEU-LACOSTE CHÂTEAU GRAVILLE-LACOSTE Country: France Region: Bordeaux Appellation(s): Bordeaux, Graves, Sauternes Producer: Hervé Dubourdieu Founded: 1890 Farming: Haute Valeur Environnementale (certified) Website: under construction Hervé Dubourdieu’s easy charm and modest disposition are complemented by his focus and ferocious perfectionism. He prefers to keep to himself, spending most of his time with his family in his modest, tasteful home, surrounded by his vineyards in the Sauternes and Graves appellations. Roûmieu-Lacoste, situated in Haut Barsac, originates from his mother’s side of the family, dating back to 1890. He also owns Château Graville-Lacoste and Château Ducasse, where he grows grapes for his Graves Blanc and Bordeaux Blanc, respectively. In the words of Dixon Brooke, “Hervé is as meticulous a person as I have encountered in France’s vineyards and wineries. Everything is kept in absolutely perfect condition, and the wines showcase the results of this care – impeccable.” Hervé is incredibly hard on himself. Despite the pedigree and complexity of the terroir and the quality of the wines, he has never been quite satisfied to rest on his laurels, always striving to outdo himself. This is most evident in his grape-sorting process for the Sauternes. Since botrytis is paramount to making great Sauternes, he employs the best harvesters available, paying them double the average wage to discern between the “noble rot,” necessary to concentrate the sugars for Sauternes, and deleterious rot. Hervé is so fastidious that he will get rid of a whole basket of fruit if a single grape with the harmful rot makes it in with healthy ones to be absolutely sure to avoid even the slightest contamination. -

Bordeaux Wines.Pdf

A Very Brief Introduction to Bordeaux Wines Rick Brusca Vers. September 2019 A “Bordeaux wine” is any wine produced in the Bordeaux region (an official Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée) of France, centered on the city of Bordeaux and covering the whole of France’s Gironde Department. This single wine region in France is six times the size of Napa Valley, and with more than 120,000 Ha of vineyards it is larger than all the vineyard regions of Germany combined. It includes over 8,600 growers. Bordeaux is generally viewed as the most prestigious wine-producing area in the world. In fact, many consider Bordeaux the birthplace of modern wine culture. As early as the 13th century, barges docked along the wharves of the Gironde River to pick up wine for transport to England. Bordeaux is the largest producer of high-quality red wines in the world, and average years produce nearly 800 million bottles of wine from ~7000 chateaux, ranging from large quantities of everyday table wine to some of the most expensive and prestigious wines known. (In France, a “chateau” simply refers to the buildings associated with vineyards where the wine making actually takes place; it can be simple or elaborate, and while many are large historic structures they need not be.) About 89% of wine produced in Bordeaux is red (red Bordeaux is often called "Claret" in Great Britain, and occasionally in the U.S.), with sweet white wines (most notably Sauternes), dry whites (usually blending Sauvignon Blanc and Semillon), and also (in much smaller quantities) rosé and sparkling wines (e.g., Crémant de Bordeaux) collectively making up the remainder. -

First Growth Vintage 2005

FIRST GROWTH Winemaker notes: VINTAGE 2005 Deep red with purple tint An intense nose of pure cassis, liquorice and subtle seaweed notes with smoky French oak. Layered blackcurrant, mint and leather on the palate combine with the elegant oak frame for a long and fine mouth-feel. A softer finish than normal with fine suede-like tannins. Appraised as one of the outstanding vintage of this label, the 2005 vintage was warm, dry and early ripening. Made for extended cellaring for 15 or more years. Decant before serving. Varietal composition Cabernet Sauvignon 91%, Merlot 9% Bottling Date March 2007 Fermentation Method Fermentation in 8 tonne static stainless steel fermenters with most parcels undergoing long maceration on skins Fermentation Time 7 days Yeast type AWRI 796/BM45 Skin Contact Time 8-30 days Barrel Origin 100% new French Oak Barriques Seguin Moreau Chateau and Taransaud Chateau Time in barrel 19 months MLF 100% Alcohol 14.7% Residual Sugar 0.37 g/L Acidity (TA) 7.8g/L pH 3.37 Viticulture Region Coonawarra Yield 2.0-3.5 tonnes/acre Date of Harvest 7-8th April Vine Age 20 years Clone Reynella Selection Soil Type Terra Rossa over Limestone The name first growth, based on an old world, specifically Bordeaux philosophy, represents the selection of the best parcels of Coonawarra fruit for Parker Coonawarra Estate. Proud of its region and humbled by critical review, including Langton's 'excellent' classification. As the custodians of Parker Coonawarra Estate, our aim is to uphold the tradition of authentic Coonawarra heritage and to add to the pedigree since the founder late John Parker began over 25 years ago. -

Addendum Regarding: the 2021 Certified Specialist of Wine Study Guide, As Published by the Society of Wine Educators

Addendum regarding: The 2021 Certified Specialist of Wine Study Guide, as published by the Society of Wine Educators This document outlines the substantive changes to the 2021 Study Guide as compared to the 2020 version of the CSW Study Guide. All page numbers reference the 2020 version. Note: Many of our regional wine maps have been updated. The new maps are available on SWE’s blog, Wine, Wit, and Wisdom, at the following address: http://winewitandwisdomswe.com/wine-spirits- maps/swe-wine-maps-2021/ Page 15: The third paragraph under the heading “TCA” has been updated to read as follows: TCA is highly persistent. If it saturates any part of a winery’s environment (barrels, cardboard boxes, or even the winery’s walls), it can even be transferred into wines that are sealed with screw caps or artificial corks. Thankfully, recent technological breakthroughs have shown promise, and some cork producers are predicting the eradication of cork taint in the next few years. In the meantime, while most industry experts agree that the incidence of cork taint has fallen in recent years, an exact figure has not been agreed upon. Current reports of cork taint vary widely, from a low of 1% to a high of 8% of the bottles produced each year. Page 16: the entry for Geranium fault was updated to read as follows: Geranium fault: An odor resembling crushed geranium leaves (which can be overwhelming); normally caused by the metabolism of sorbic acid (derived from potassium sorbate, a preservative) via lactic acid bacteria (as used for malolactic fermentation) Page 22: the entry under the heading “clone” was updated to read as follows: In commercial viticulture, virtually all grape varieties are reproduced via vegetative propagation. -

Parker, Wine Spectator and Retail Prices of Bordeaux Wines in Switzerland: Results from Panel Data 1995 - 2000

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kugler, Peter; Kugler, Claudio Working Paper Parker, Wine Spectator and Retail Prices of Bordeaux Wines in Switzerland: Results from Panel Data 1995 - 2000 WWZ Discussion Paper, No. 2010/10 Provided in Cooperation with: Center of Business and Economics (WWZ), University of Basel Suggested Citation: Kugler, Peter; Kugler, Claudio (2010) : Parker, Wine Spectator and Retail Prices of Bordeaux Wines in Switzerland: Results from Panel Data 1995 - 2000, WWZ Discussion Paper, No. 2010/10, University of Basel, Center of Business and Economics (WWZ), Basel, http://dx.doi.org/10.5451/unibas-ep61222 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/123411 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Wine-Book-210709.Pdf

02 04 08 09 21 52 53 54 02 04 08 09 21 52 53 54 2 SPARKLING Brut, Naveran — Cava (Penedès), 2018 .............................................................................................................. 8 Brut Rosé, Michel Briday – Bourgogne, NV......................................................................................................... 12 Brut, Taittinger — Champagne, NV.................................................................................................................... 18 ROSÉ Grenache, Cinsault, Syrah Peyrassol — Mediterranee 2020 ............................................................................ 10 Touriga Nacional, Maçanita - Douro 2019 ......................................................................................................... 14 WHITE Melon de Bourgogne, Eric Chevalier — Muscadet Côtes de Grand Lieu 2018 ................................................... 10 Sauvignon Blanc, Vincent Delaporte — Sancerre 2019 ..................................................................................... 16 Sauvignon Blanc, Spy Valley — Marlborough 2020............................................................................................ 11 Pinot Grigio, Jermann — Fruili-Venezia Giulia 2019 ........................................................................................... 14 Albariño, Fillaboa — Rias Baixas 2018 ................................................................................................................ 11 Grüner Veltliner, “Crazy Creatures,” Malat — -

Bordeaux, France Itinerary-1

Bordeaux, France Wine Tour May 16-24, 2014 Day 1 Friday, May 16, 2014 We will depart the USA to embark on this exciting wine journey to the Bordeaux Region of France. Day 2 Saturday, May 17, 2014 Upon arrival at Bordeaux airport we will be met and transferred to our hotel in the city center. This afternoon we will embark on a walking tour of Bordeaux. Tonight the group will gather for a Welcome Dinner at a local restaurant in Bourdeaux (drinks not included). Hotel Burdigala (standard room) seven nights with breakfast Contemporary elegance in the heart of Bordeaux, the wine capital. Never has a place been so aptly named. The Hotel Burdigala takes its name from the ancient Gallo-Roman settlement which became Bordeaux. Located just a stone’s throw from the historic center which embodies all the charm of the modern day town, and is a UNESCO world heritage site since 2007. Behind the white stone lobby a stylish and discreet spirit, with friendly service is revealed. Restful and spacious, the rooms are havens of serenity. Enjoy gourmet cuisine at the ‘LaTable de Burdigala’ Restaurant or sip a glass of something wonderful in the intimate atmosphere of the Bacchus Bar. Wine lovers will find the regions greatest crus classes here. After all, is Bourdeax not the wine capital of the world? Day 3 Sunday, May 18, 2014 We will enjoy breakfast at the hotel before our departure to the town of Lege Cap Ferret to visit this typical oyster village where we will experience oyster tasting with a glass of white wine. -

2014 Spottswoode Estate Cabernet Sauvignon

2014 Spottswoode Estate Cabernet Sauvignon Wine Advocate, Robert Parker 96+ POINTS An extraordinary wine of profound and complex character displaying all the attributes expected of a classic wine of its variety. Wines of this caliber are worth a special effort to find, purchase, and consume. This first-growth estate in St. Helena has produced a 2014 Cabernet Sauvignon that is a blend of 85% Cabernet Sauvignon, 10% Cabernet Franc and 5% Petit Verdot. It is certainly one of the wines of the vintage. Gorgeously opaque purple, it offers up notes of spring flowers, blueberries, blackcurrants, some baking spice and graphite. It is full-bodied, concentrated and rich, with layers of fruit. The wine builds and builds on the palate, with a great finish of 45+ seconds. This is a sensational 2014 to drink over the next 20+ years. (December 2016) ————— Wine Spectator, James Molesworth First impressions of more than 20 young wines, along with a few library vintages, from 5 Napa all-stars. • • • • Spottswoode: A Quintessential California Wine Story There’s a delicacy to the Spottswoode Cabernet, but the wine is no pushover. Sneaky long and with tensile strength, it’s a yoga pose held for minutes, in stark contrast with the stereotypical Napa Cab's bodybuilder reps. It has a uniquely pure feel, and while it’s in a less “obvious” style, its ageability is clear. The wine, like the estate, has the reach to connect Napa’s past to its future. • • • • The 2014 shows the character of the vintage that is steadily winning me over as the most intriguing of these past three big years, with notes of sagebrush and savory amid the tightly focused cassis and plum flavors.