Wine Paper – Copie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domaine Luneau-Papin Muscadet from Domaine Luneau-Papin

Domaine Luneau-Papin Muscadet from Domaine Luneau-Papin. Pierre-Marie Luneau and Marie Chartier. Photo by Christophe Bornet. Pierre and Monique Luneau. Photo by Christophe Bornet. Profile Pierre-Marie Luneau heads this 50-hectare estate in Le Landreau, a village in the heart of Muscadet country, where small hamlets dot a landscape of vineyards on low hills. Their estate, also known as Domaine Pierre de la Grange, has been in existence since the early 18th century when it was already planted with Melon de Bourgogne, the Muscadet appellation's single varietal. After taking over from his father Pierre in 2011, Pierre-Marie became the ninth generation to make wine in the area. Muscadet is an area where, unfortunately, a lot of undistinguished bulk wine is produced. Because of the size of their estate, and of the privileged terroir of the villages of Le Landreau, Vallet and La Chapelle Heulin, the Luneau family has opted for producing smaller cuvées from their several plots, which are always vinified separately so as to reflect their terroir's particular character. The soil is mainly micaschist and gneiss, but some plots are a mix of silica, volcanic rocks and schist. The estate has a high proportion of old vines, 40 years old on average, up to 65 years of age. The harvest is done by hand -also a rarity in the region- to avoid any oxidation before pressing. There is an immediate light débourbage (separation of juice from gross lees), then a 4-week fermentation at 68 degrees, followed by 6 months of aging in stainless-steel vats on fine lees. -

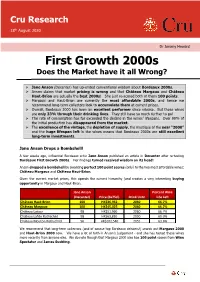

First Growth 2000S Does the Market Have It All Wrong?

Cru Research 18th August 2020 Dr Jeremy Howard First Growth 2000s Does the Market have it all Wrong? ➢ Jane Anson (Decenter) has up-ended conventional wisdom about Bordeaux 2000s. ➢ Anson claims that market pricing is wrong and that Château Margaux and Château Haut-Brion are actually the best 2000s! She just re-scored both of them 100 points. ➢ Margaux and Haut-Brion are currently the most affordable 2000s, and hence we recommend long-term collectors look to accumulate them at current prices. ➢ Overall, Bordeaux 2000 has been an excellent performer since release. But these wines are only 33% through their drinking lives. They still have so much further to go! ➢ The rate of consumption has far exceeded the decline in the wines’ lifespans. Over 99% of the initial production has disappeared from the market. ➢ The excellence of the vintage, the depletion of supply, the mystique of the year “2000” and the huge lifespan left in the wines means that Bordeaux 2000s are still excellent long-term investments. Jane Anson Drops a Bombshell! A few weeks ago, influential Bordeaux critic Jane Anson published an article in Decanter after re-tasting Bordeaux First Growth 2000s. Her findings turned received wisdom on its head! Anson dropped a bombshell by awarding perfect 100 point scores (only) to the two most affordable wines: Château Margaux and Château Haut-Brion. Given the current market prices, this upends the current hierarchy (and creates a very interesting buying opportunity in Margaux and Haut-Brion. Jane Anson Percent Wine (Decanter) Price (6x75cl) Drink Until Life Left Château Haut-Brion 100 HK$36,952 2060 66.7% Château Margaux 100 HK$45,025 2060 66.7% Château Latour 98 HK$51,960 2060 66.7% Château Lafite Rothschild 98 HK$63,810 2050 60.0% Château Mouton Rothschild 96 HK$102,540 2055 63.6% We recommend that long-term collectors (and of course top Bordeaux drinkers!) search out Margaux 2000 and Haut-Brion 2000 now. -

First Growth SHOWDOWN

Roberson Wine presents: First Growth SHOWDOWN Thursday March 5th 2009 fIrst growth showdown The Vintages “1995 is an excellent to outstanding1995 vintage of consistently top-notch red wines.” Robert Parker The early 1990s were a dark period for the Bordelais, and ‘95 was the first high quality vintage since 1990. ‘91 through to ‘94 was a procession of poor to average vintages that yielded very few excellent wines, but a superb (and consistent) start to ‘95 led into the driest summer for 20 years and subsequently the first serious En Primeur campaign since the start of the decade. The rain that came in mid-September soon passed, and the top properties from the Haut-Medoc allowed more time for their Cabernet to fully ripen before picking. Tonight we will taste four of the second wines from the ‘95 vintage, all of which should be hitting their stride about now with more room left for development in the future. “T his is one of the most perfect 1985vintages, both for drinking now and for keeping. It is certainly my favourite vintage of this splendid decade, typifying claret at its best.” Michael Broadbent After the disastrous 1984 vintage and one of the coldest winters on record, the Chateaux owners of Bordeaux were apprehensive about the ‘85 vintage. What ensued was a long and remarkably consistent (albeit dotted with bouts of rain) growing season that culminated in absolutely perfect harvest conditions and beautifully ripe fruit. The properties that harvested latest of all (including the first growths) reaped the benefits and produced supple and silky wines that have aged beautifully. -

2021 Oregon Harvest Internship Sokol Blosser Winery Dundee, OR

2021 Oregon Harvest Internship Sokol Blosser Winery Dundee, OR Job Description: Sokol Blosser Winery, located in the heart of Oregon's wine country, is one of the state's most well- known wineries. For the upcoming 2021 harvest, we are looking to hire multiple experienced cellar hands, with one individual focused on lab/fermentation monitoring. Our ideal candidates will have 2+ previous harvest experiences, but not required. Amazing forklift skills are a bonus! Our 2021 harvest will focus on the production of both small batch Pinot Noir for our Sokol Blosser brand and large format fermentation for our Evolution brand. Additionally, we work with Pinot Gris, Rose of Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, various sparkling bases, Gamay and aromatic varieties such as Riesling, and Müller-Thurgau. Our estate vineyard is certified organic and our company is B-Corp certified. Cellar hand responsibilities • Cleaning and more cleaning • Attention to detail/safety • Harvest tasks including but not limited to (cap management, racking, inoculations, barrel work, cleaning, forklift driving, etc.) • Ability to lift up to 50 lbs., work long hours in variable conditions, follow directions, and accurately fill out work orders • Potential support to lab work including running pH/TA, using equipment such as densitometers/refractometers and data entry We provide • Housing on site • Lunches, and dinners on late nights • Cats and dogs for all your cuteness needs • Football and Frisbee time • End of day quality time with co-workers, work hard-play hard! No phone calls, please. Send your resume and cover letter to [email protected] with the subject line “Harvest 2021”. -

2010 58% Merlot & 42% Cabernet Franc Columbia Valley

2010 58% Merlot & 42% Cabernet Franc Columbia Valley This vintage was sourced from the acclaimed Conner Lee Vineyard with 5% from Champoux Vineyard. Caleb has worked with Conner Lee’s phenomenal merlot and cabernet franc since its first harvest in 1994. Conner Lee is a cool site in a warm, sunny region of Washington state. In the eastern Washington desert, the hot summer ripens the fruit, while the diurnal temperatures keep the acids high and the pH low. Buty has bottled its own blend of merlot & cabernet franc since 2000, our inaugural vintage. Like the yields of Bordeaux First Growth harvests, in a normal year at Conner Lee we grow 30 HL per hectare, equal to two tons per acre or 3.5 pounds per plant. But 2010 was the coolest vintage in thirty years, so we further cut yields in the summer to 20 HL per hectare to ensure fully ripe character for our wine. We harvested our merlot by hand on October 7. Cabernet franc we harvested on October 22 at potential alcohols of 14.3%. We hand-sorted and destemmed with gravity transfer to tank, which allowed us to preserve the fruit's abundant aromatics. We aerated during fermentation in wood tanks for two weeks and selected only free-run wine to blend. Aged 14 months in Taransaud and Bel Air French Château barrels, half of which were new, the wines rested unracked until bottling in December 2011. This is one of Washington's fabulous wines that though very pretty in its youth, will also be very long lived. -

Ft Extrazyme Terroir (En)

DATA SHEET EXTRAZYME TERROIR ENZYMATIC PREPARATIONS Enzymes for maceration and extraction highly concentrated. ŒNOLOGICAL APPLICATIONS EXTRAZYME TERROIRis a pectolytic enzyme preparation with highly concentrated additional capabilities that considerably accelerates the breakdown of the cell walls making up the grape's berry. Thanks to its wide and active spectrum, EXTRAZYME TERROIR is the enzyme formula best adapted to preparing red-grape wines of high potential. Indeed, with this type of grape harvest, it provides rapid colour stabilisation, concentrating the structure whilst also encapsulating it through the action of the polysaccharides arising from the hydrolysed pectins. With poorer grapes, EXTRAZYME TERROIR provides significant gains in colour and tannins whilst also reducing the mechanical pulverisation and other operations needed for their extraction. The ratio of free-run juice to pressing wine is improved, which contributes to the overall quality of the resulting wine, giving more volume in the mouth and more structure but less astringency. PROPERTIES - Origin: Concentrated and purified extracts from various strains of Aspergillus niger. - Main enzymatic reactions: polygalacturonase, pectin esterase, pectin lyase. Suppresses secondary pectolytic enzymes for the hydrolysis of the pectic hairy regions, as well as hemi-cellulase and cellulase enzymes that help to weaken the grape berry. Suppresses secondary glycosidase enzymes. - Cinnamyl esterase reaction: average. - Format: Perfectly soluble micro-granules. DOSE RATE • 3 to 6 -

Wine Flavor 101C: Bottling Line Readiness Oxygen Management in the Bottle

Wine Flavor 101C: Bottling Line Readiness Oxygen Management in the Bottle Annegret Cantu [email protected] Andrew L. Waterhouse Viticulture and Enology Outline Oxygen in Wine and Bottling Challenges . Importance of Oxygen in Wine . Brief Wine Oxidation Chemistry . Physical Chemistry of Oxygen in Wine . Overview Wine Oxygen Measurements . Oxygen Management and Bottling Practices Viticulture and Enology Importance of Oxygen during Wine Production Viticulture and Enology Winemaking and Wine Diversity Louis Pasteur (1822-1895): . Discovered that fermentation is carried out by yeast (1857) . Recommended sterilizing juice, and using pure yeast culture . Described wine oxidation . “C’est l’oxygene qui fait le vin.” Viticulture and Enology Viticulture and Enology Viticulture and Enology Importance of Oxygen in Wine QUALITY WINE OXIDIZED WINE Yeast activity Color stability + Astringency reduction Oxygen Browning Aldehyde production Flavor development Loss of varietal character Time Adapted from ACS Ferreira 2009 Viticulture and Enology Oxygen Control during Bottling Sensory Effect of Bottling Oxygen Dissolved Oxygen at Bottling . Low, 1 mg/L . Med, 3 mg/L . High, 5 mg/L Dimkou et. al, Impact of Dissolved Oxygen at Bottling on Sulfur Dioxide and Sensory Properties of a Riesling Wine, AJEV, 64: 325 (2013) Viticulture and Enology Oxygen Dissolution . Incorporation into juices & wines from atmospheric oxygen (~21 %) by: Diffusion Henry’s Law: The solubility of a gas in a liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of the gas above the liquid; C=kPgas Turbulent mixing (crushing, pressing, racking, etc.) Increased pressure More gas molecules Viticulture and Enology Oxygen Saturation . The solution contains a maximum amount of dissolved oxygen at a given temperature and atmospheric pressure • Room temp. -

Sauvignon Blanc: Past and Present by Nancy Sweet, Foundation Plant Services

Foundation Plant Services FPS Grape Program Newsletter October 2010 Sauvignon blanc: Past and Present by Nancy Sweet, Foundation Plant Services THE BROAD APPEAL OF T HE SAUVIGNON VARIE T Y is demonstrated by its woldwide popularity. Sauvignon blanc is tenth on the list of total acreage of wine grapes planted worldwide, just ahead of Pinot noir. France is first in total acres plant- is arguably the most highly regarded red wine grape, ed, followed in order by New Zealand, South Africa, Chile, Cabernet Sauvignon. Australia and the United States (primarily California). Boursiquot, 2010. The success of Sauvignon blanc follow- CULTURAL TRAITS ing migration from France, the variety’s country of origin, Jean-Michel Boursiqot, well-known ampelographer and was brought to life at a May 2010 seminar Variety Focus: viticulturalist with the Institut Français de la Vigne et du Sauvignon blanc held at the University of California, Davis. Vin (IFV) and Montpellier SupAgro (the University at Videotaped presentations from this seminar can be viewed Montpellier, France), spoke at the Variety Focus: Sau- at UC Integrated Viticulture Online http://iv.ucdavis.edu vignon blanc seminar about ‘Sauvignon and the French under ‘Videotaped Seminars and Events.’ clonal development program.’ After discussing the his- torical context of the variety, he described its viticultural HISTORICAL BACKGROUND characteristics and wine styles in France. As is common with many of the ancient grape varieties, Sauvignon blanc is known for its small to medium, dense the precise origin of Sauvignon blanc is not known. The clusters with short peduncles, that make it appear as if variety appears to be indigenous to either central France the cluster is attached directly to the shoot. -

Château Graville-Lacoste

CHÂTEAU DUCASSE CHÂTEAU ROUMIEU-LACOSTE CHÂTEAU GRAVILLE-LACOSTE Country: France Region: Bordeaux Appellation(s): Bordeaux, Graves, Sauternes Producer: Hervé Dubourdieu Founded: 1890 Farming: Haute Valeur Environnementale (certified) Website: under construction Hervé Dubourdieu’s easy charm and modest disposition are complemented by his focus and ferocious perfectionism. He prefers to keep to himself, spending most of his time with his family in his modest, tasteful home, surrounded by his vineyards in the Sauternes and Graves appellations. Roûmieu-Lacoste, situated in Haut Barsac, originates from his mother’s side of the family, dating back to 1890. He also owns Château Graville-Lacoste and Château Ducasse, where he grows grapes for his Graves Blanc and Bordeaux Blanc, respectively. In the words of Dixon Brooke, “Hervé is as meticulous a person as I have encountered in France’s vineyards and wineries. Everything is kept in absolutely perfect condition, and the wines showcase the results of this care – impeccable.” Hervé is incredibly hard on himself. Despite the pedigree and complexity of the terroir and the quality of the wines, he has never been quite satisfied to rest on his laurels, always striving to outdo himself. This is most evident in his grape-sorting process for the Sauternes. Since botrytis is paramount to making great Sauternes, he employs the best harvesters available, paying them double the average wage to discern between the “noble rot,” necessary to concentrate the sugars for Sauternes, and deleterious rot. Hervé is so fastidious that he will get rid of a whole basket of fruit if a single grape with the harmful rot makes it in with healthy ones to be absolutely sure to avoid even the slightest contamination. -

Bordeaux Wines.Pdf

A Very Brief Introduction to Bordeaux Wines Rick Brusca Vers. September 2019 A “Bordeaux wine” is any wine produced in the Bordeaux region (an official Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée) of France, centered on the city of Bordeaux and covering the whole of France’s Gironde Department. This single wine region in France is six times the size of Napa Valley, and with more than 120,000 Ha of vineyards it is larger than all the vineyard regions of Germany combined. It includes over 8,600 growers. Bordeaux is generally viewed as the most prestigious wine-producing area in the world. In fact, many consider Bordeaux the birthplace of modern wine culture. As early as the 13th century, barges docked along the wharves of the Gironde River to pick up wine for transport to England. Bordeaux is the largest producer of high-quality red wines in the world, and average years produce nearly 800 million bottles of wine from ~7000 chateaux, ranging from large quantities of everyday table wine to some of the most expensive and prestigious wines known. (In France, a “chateau” simply refers to the buildings associated with vineyards where the wine making actually takes place; it can be simple or elaborate, and while many are large historic structures they need not be.) About 89% of wine produced in Bordeaux is red (red Bordeaux is often called "Claret" in Great Britain, and occasionally in the U.S.), with sweet white wines (most notably Sauternes), dry whites (usually blending Sauvignon Blanc and Semillon), and also (in much smaller quantities) rosé and sparkling wines (e.g., Crémant de Bordeaux) collectively making up the remainder. -

Varietal Mead Comparison

It Ain’t Over ‘til it’s Over Mead Finishing Techniques Gordon Strong Curt Stock 2002 Mazer Cup winner 2005 Meadmaker of the Year 5 NHC mead medals 7 NHC mead medals BJCP Mead Judge BJCP Mead Judge Mead is Easy – Except When it Isn’t Making Mead is a Simple Process Mead isn’t as Predicable as Beer Significant Money and Time Investment Recognizing Great Mead What Can You Do if Your Mead Needs Help? When are you Done? Modern Mead Making Sufficient Honey, Fruit, Fermentables Quality In, Quality Out No Boil Staggered Nutrient Additions Yeast Preparation Fruit in Primary Fermentation Management See BJCP Mead Exam Study Guide for details Evaluating Your Mead Give it Time before Tasting Basic Triage Good to Go – Package, Consume Dump – Don’t Waste Your Time Tweak – Here is Where We Focus Look for Clean, Complete Fermentation Absence of Flaws Balance Issues Can Be Fixed “Balance” doesn’t mean all components equal Everything in the right amount FOR THE STYLE Pleasant, Harmonious, Enjoyable Elements of Balance Sweetness, Honey Flavor, Fruit Flavor Acidity, Tannin, Alcohol Sweetness:Acid is Most Important Not Just Proportion, but Intensity Acid and Tannin Work Together (Structure) Tannin Adds Dryness and Body Honey vs. Added Flavor Ingredients Mouthfeel (Body, Carbonation) Common Balance Problems Too Dry – Over-attenuated, Not Enough Honey Too Sweet – Stuck, Stalled Fermentation? Flabby – Acid not High Enough for Sweetness Balance Off – Too Much or Not Enough Flavor Doesn’t Taste Good – Ingredient Quality? Too -

Ft Tanin Sr Terroir (En)

DATA SHEET TANIN SR TERROIR TANINS ŒNOLOGICAL APPLICATIONS TANIN SR TERROIR is a combination of catechin tannins reinforced with grape seed tannins. Added during maceration of red wine it helps to stabilise colour and reinforces the antioxidant properties of sulphur dioxide. It can also be used post fermentation to improve structure and help colour stability. INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE The powder should be dissolved in a small volume of warm water and added directly to the wine via a remontage. Ensure thorough mixing. TANIN SR TERROIR can also be used to revitalise wines which have become tired due to prolonged storage. DOSE RATE At our customers' request, TANIN SR TERROIR is available as a special made-up solution at 100 g/L. • During winemaking: - Maceration: 5 à 15 cL/hL - Winemaking: 5 à 15 cL/hL • Ageing: 5 à 30 cL/hL POWDER: • During winemaking: This may be added during two of the winemaking operations: - During maceration: add 5 to 15 g of TANIN SR TERROIR per 100 litres at the start of alcoholic fermentation when pumping over without aeration. - During winemaking: add 5 to 15 g of TANIN SR TERROIR per 100 litres when pumping over, with aeration, or during racking and returning. • During ageing: Adding TANIN SR TERROIR can help improve the structure of wines that are 'tired' after being kept in a vat or a barrel. Add the product at a quantity of 5 to 30 g of TANIN SR TERROIR per 100 litres of wine. At the time of adding the product, we recommend aeration of the wine (and adjusting with BISULFITE, if necessary).