Annexes - National REDD+ Strategy and Its Implementation Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 89 Area & Population

Table :- 1 89 AREA & POPULATION AREA, POPULATION AND POPULATION DENSITY OF PAKISTAN BY PROVINCE/ REGION 1961, 1972, 1981 & 1998 (Area in Sq. Km) (Population in 000) PAKISTAN /PROVINCE/ AREA POPULATION POPULATION DENSITY/Sq: Km REGION 1961 1972 1981 1998 1961 1972 1981 1998 Pakistan 796095 42880 65309 84254 132351 54 82 106 166 Total % Age 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 Sindh 140914 8367 14156 19029 30440 59 101 135 216 % Age share to country 17.70 19.51 21.68 22.59 23.00 Punjab 205345 25464 37607 47292 73621 124 183 230 358 % Age share to country 25.79 59.38 57.59 56.13 55.63 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 74521 5731 8389 11061 17744 77 113 148 238 % Age share to country 9.36 13.37 12.84 13.13 13.41 Balochistan 347190 1353 2429 4332 6565 4 7 12 19 % Age share to country 43.61 3.16 3.72 5.14 4.96 FATA 27220 1847 2491 2199 3176 68 92 81 117 % Age share to country 3.42 4.31 3.81 2.61 2.40 Islamabad 906 118 238 340 805 130 263 375 889 % Age share to country 0.11 0.28 0.36 0.4 0.61 Source: - Population Census Organization, Government, of Pakistan, Islamabad Table :- 2 90 AREA & POPULATION AREA AND POPULATION BY SEX, SEX RATIO, POPULATION DENSITY, URBAN PROPORTION HOUSEHOLD SIZE AND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE OF BALOCHISTAN 1998 CENSUS Population Pop. Avg. Growth DIVISION / Area Sex Urban Pop. Both density H.H rate DISTRICT (Sq.km.) Male Female ratio Prop. -

5:30 PM 18 July-2019 Government of Pakistan Ministry of Water

5:30 PM 18th July-2019 Government of Pakistan Ministry of Water Resources Office of Chief Engineering Advisor/ Chairman, Federal Flood Commission 6-Attaturk Avenue, G-5/1, Islamabad Fax No. 051-9244621 & www.ffc.gov.pk Monsoon Activity Likely to Persist in Upper / Central Parts of Pakistan Till Monday (22nd July 2019) Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD), Islamabad, has issued a Press Release on the developing meteorological situation in the context of monsoon currents from Arabian Sea. Silent features are: "Moderate Monsoon Currents from Arabian Sea are still penetrating in upper and central parts of Pakistan and likely to continue till Monday (22nd July 2019). Under the influence of this weather system, more wind-thunderstorm/rains (Isolated Moderate to Heavy Falls) are expected at scattered places in Islamabad, Punjab (Rawalpindi, Gujranwala, Lahore, Sargodha, Sahiwal & Faisalabad Divisions), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Hazara Division) and Kashmir, while at isolated places in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Malakand, Peshawar, Mardan, Kohat & Bannu Divisions), Punjab (Bahawalpur & D.G. Khan Divisions), Sindh (Sukkur Division) and Balochistan (Zhob Division) during the period. As a result, possibility of landslides in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Hazara Division) and Kashmir cannot be ruled out during the period. With above likely meteorological situation in view, all concerned authorities are advised to watch the weather situation and take all necessary precautionary measures to avoid loss of precious human lives and damage to private & public property. Distribution: 1. Minister for Water Resources, Islamabad. 2. Minister for Planning, Development & Reforms, Islamabad. 3. Secretary to the Prime Minister, Prime Minister’s Office, Islamabad. 4. Secretary, Ministry of Water Resources, Islamabad. 5. -

Climate Change

Chapter 16 Climate Change Pakistan is vulnerable to the effects of climate change which has occurred due to rapid industrialization with substantial geopolitical consequences. As things stand, the country is at a crossroads for a much warmer world. According to German Watch, Pakistan has been ranked in top ten of the countries most affected by climate change in the past 20 years. The reasons behind include the impact of back-to-back floods since 2010, the worst drought episode (1998-2002) as well as more recent droughts in Tharparkar and Cholistan, the intense heat wave in Karachi (in Southern Pakistan generally) in July 2015, severe windstorms in Islamabad in June 2016, increased cyclonic activity and increased incidences of landslides and Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) in the northern parts of the country. Pakistan’s climate change concerns include increased variability of monsoons, the likely impact of receding Hindu Kush-Karakoram-Himalayan (HKH) glaciers due to global warming and carbon soot deposits from trans-boundary pollution sources, threatening water inflows into Indus River System (IRS), severe water-stressed conditions particularly in arid and semi-arid regions impacting agriculture and livestock production negatively, decreasing forest cover and increased level of saline water in the Indus delta also adversely affecting coastal agriculture, mangroves and breeding grounds of fish. Box-I: Water sector challenges in the Indus Basin and impact of climate change Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) took stock of Pakistan's water resource availability, delineating water supply system and its sources including precipitation and river flows and the impact of increasing climatic variability on the water supply system. -

Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on Polio Eradication in Pakistan

Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on Polio Eradication in Pakistan Karachi & Islamabad, Pakistan, 8-12 January 2019 Acronyms AFP Acute Flaccid Paralysis bOPV Bivalent Oral Polio Vaccine C4E Communication for Eradication CBV Community-Based Vaccination CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CHW Community Health Workers cVDPV2 Circulating Vaccine Derived Polio Virus Type 2 CWDP Central Development Working Party DC Deputy Commissioner DPCR District Polio Control Room DPEC District Polio Eradication Committee EI Essential Immunization ES Environnemental Sample EOC Emergency Operations Centers EPI Expanded Programme on Immunization EV Entero-Virus FCVs Female Community Vaccinators FGD Focus Group Discussion FRR Financial Resource Requirements GAVI Global Alliance for Vaccines GB Gilgit Baltistan GOP Government of Pakistan GPEI Global Polio Eradication Initiative HRMP High-Risk Mobile Populations ICM Intra-campaign Monitoring IPV Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine KP Khyber Pakhtunkhwa KPTD Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Tribal Districts LEAs Law Enforcing Agents LPUCs Low Performing Union Councils LQAS Lot Quality Assurance Sampling mOPV Monovalent Oral Polio Vaccine NA Not Available Children NA3 Not Available Children Out-of-District NEAP National Emergency Action Plan NEOC National Emergency Operation Center NID National Immunization Day NGO Non-Governmental Organization NPAFP Non-Polio Acute Flaccid Paralysis NTF National Task Force NPMT National Polio Management Team N-STOP National Stop Transmission of Poliomyelitis PC1 Planning Commission -

Government of Pakistan Ministry of Climate Change National Disaster Management Authority (Prime Minister’S Office) Islamabad

Page 1 of 5 Government of Pakistan Ministry of Climate Change National Disaster Management Authority (Prime Minister’s Office) Islamabad DAILY SITUATION REPORT NO – 53 MONSOON 2016 (PERIOD COVERED: 1300 HRS 31 AUGUST 2016 – 1300 HRS 1 SEPTEMBER 2016) 1. Rivers Flow Situation Reported by Flood Forecasting Division. Annex A. 2. Past Meteorological Situation and Future Forecast by PMD. Annex B. 3. Dam Levels Max Conservation Level Current Level Serial Reservoirs Percentage (Feet) (Feet) a. Tarbela 1,550.00 1,544.07 99.6% b. Mangla 1,242.00 1,236.70 99.6% 4. Significant Events. Nothing to Report. 5. Road Situation (NHA and Respective Provinces). All roads across the Country are clear for all types of traffic. 6. Railway Situation. Nothing to Report. 7. Preliminary Losses / Damages Reported. Overall details of losses / damages during Monsoon Season 2016 are at Annex C. 8. Relief Provided Overall details of relief provided during Monsoon Season 2016 are at Annex D. 9. Any Critical Activity to Report. Nothing to Report. 10. Any Recommendation. Nil. Page 2 of 5 Annex A To NDMA SITREP No-53 dated 1 September 2016 RIVERS FLOW SITUATION REPORTED BY FLOOD FORECASTING DIVISION Rivers Actual Observed Flow Danger River / Forecast for Design Forecasted Flood Level Structure Next 24 hrs Capacity In Flow Out Flow Level (Inflow) (V. High (Inflow) Flood) River Indus Tarbela 1,500 143.0 111.9 130 – 150 Below Low 650 No Significant Kalabagh 950 148.1 140.5 -do- 650 Change Chashma 950 163.9 158.1 -do- -do- 650 Taunsa 1,100 145.6 129.5 -do- -do- 650 Guddu 1,200 -

Bonded Labour in Agriculture: a Rapid Assessment in Sindh and Balochistan, Pakistan

InFocus Programme on Promoting the Declaration on Fundamental Principles WORK IN FREEDOM and Rights at Work International Labour Office Bonded labour r in agriculture: e a rapid assessment p in Sindh and Balochistan, a Pakistan P Maliha H. Hussein g Abdul Razzaq Saleemi Saira Malik Shazreh Hussain n i k r Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour o DECLARATION/WP/26/2004 ISBN 92-2-115484-X W WP. 26 Working Paper Bonded labour in agriculture: a rapid assessment in Sindh and Balochistan, Pakistan by Maliha H. Hussein Abdul Razzaq Saleemi Saira Malik Shazreh Hussain International Labour Office Geneva March 2004 Foreword In June 1998 the International Labour Conference adopted a Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its Follow-up that obligates member States to respect, promote and realize freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour, the effective abolition of child labour, and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.1 The InFocus Programme on Promoting the Declaration is responsible for the reporting processes and technical cooperation activities associated with the Declaration; and it carries out awareness raising, advocacy and research – of which this Working Paper is an example. Working Papers are meant to stimulate discussion of the questions covered by the Declaration. They express the views of the author, which are not necessarily those of the ILO. This Working Paper is one of a series of Rapid Assessments of bonded labour in Pakistan, each of which examines a different economic sector. -

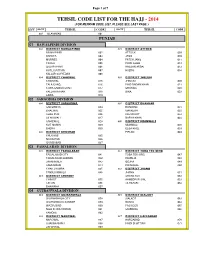

Tehsil Code List for the Hajj

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ - 2014 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

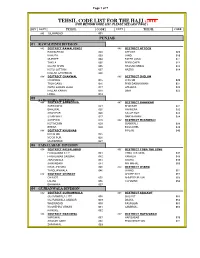

Tehsil Code List 2014

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ -2016 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

Statement of Complaints 2016 KP Right to Information Commission Email: [email protected]

Statement of Complaints 2016 KP Right to Information Commission Email: [email protected] Complaint S.NO. Complaint No. Name Of Complainant Public Body/Department Information Sought Status Status Registration Date Information provided 01 01382 04-01-2016 Muhammad Imran PPO, CPO Peshawar Copies of Letters Closed Case closed on 09-03-2016 Information provided 02 01383 04-01-2016 Javed Khattak CMO Lacchi Kohat Details of Contracts Closed Case closed on 13-1-2016 Directorate of Labor Seniority list of Junior Clerk, Information provided 03 01384 04-01-2016 Zaheer Hussain Closed Peshawar etc. Case closed on 20-1-2016 Information provided 04 01385 04-01-2016 Mumtaz Ahmad Bhatti DG small Dams Peshawar PC-1 and bill of quantities of small dams Closed Case closed on 21-07-2016 Information provided 05 01386 04-01-2016 Khurram Mehtab University of Haripur Contract Copies of the University employees Closed Case closed on 06-02-2017 Strength of employees,copies of advertisement, 06 01387 04-01-2016 M. Naeem UOS, Swabi Summon dated 24/11/2016 Complainant and Dep Open allocation of grants, etc. Details of criteria, seats for disable students,online Information provided 07 01388 04-01-2016 M. Naeem AWKU Mardan Closed system for admission, etc. Case closed on 02-02-2016 List of Govt. girls primary school, list of non Information provided 08 01389 04-01-2016 Asad Ali DEO (F) Abbottabad Closed functional schools. Case closed on 11-3-2016 Statement of Complaints 2016 KP Right to Information Commission Email: [email protected] Complaint S.NO. -

47281-001: National Highway Network Development In

Corrective Action Plan Corrective Action Plan (Up-Gradation, Widening & Improvement of National Highway N-70 from Qila Saifullah to Loralai and to Waigum Rud and National Highway N-50 from Zhob to Mughal Kot) (August 2019) PAK: National Highway Network Development in Balochistan Project N-70 (Qila Saifullah to Loralai to Waigum Rud) N-50 (Zhob to Killi Khudae Nazar to Mughal Kot) Prepared by National Highways Authority for the Asian Development Bank. NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and its agencies ends on 30 June. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This Corrective Action Plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. National Highway Authority (NHA) Government of Pakistan (ADB Loan 3134-PAK) National Highway Network Development in Balochistan Project Widening and Improvement Project Of N-70 Road Qila Saifullah-Loralai-Waigum Rud Section (120 km) And Zhob Mughal Kot N-50 (81 km) Corrective Action Plan (CAP) August 2019 Prepared by National Highway Authority (NHA) Ministry of Communications, Government of Pakistan Corrective Action Plan (CAP) National Highway Authority Pakistan TABLE OF CONTENTS A. -

China Launches Cargo Flight for New Space Station

Fawad asks Opp Bushra launches ISLAMABAD (APP): Minister LAHORE (APP): Prime for Information and Broadcasting Minister's wife Bushra Imran Fawad Saturday asked the opposi- Saturday inaugurated the Shaikh tion parties to focus on construc- Abul Hasan Ash Shadhili tive and positive activities instead Research Hub for promotion of of indulging in undue political ral- Sufism, science and technology in lies. He said the opposition parties the country during a solemn cere- were confused besides their direc- mony here at the the Punjab Sports tion and intentions were in contra- Board (PSB) E-Library building at diction to each others view. Nishter Park Sports Complex. @thefrontierpost First national English daily published from Peshawar, Islamabad, Lahore, Quetta, Karachi and Washington D.C www.thefrontierpost.com Vol. XXXVIII No. 137 Regd. No. 241 SHAWWAL 18 1442 -- SUNDAY, MAY 30 2021 PESHAWAR EDITION 12 PAGES Price. 20 Egypt China launches to Hamas: Pak., Iraq mull cooperation Ceasefire deal cargo flight for must include in security, trade, education prisoner swap BAGHDAD (APP): during the meeting, they port for the sovereignty and try. GAZA CITY (Agencies): Pakistan and Iraq Saturday also discussed the efforts territorial integrity of Iraq, Also, Qureshi met with Hamas has reportedly deliberated over the possi- for Afghan peace as they said a press release. Prime Minister of Iraq new space station received a message from bilities of bilateral coopera- did not want the country to Acknowledging the Mustafa Al-Kadhimi and Egypt that continuing tion in multiple fields be pushed back to the situa- unyielding efforts and sac- proposed the development BEIJING (dpa): China's The Tianzhou 2 is need- are to stay for three months. -

Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group on Polio Eradication in Pakistan

Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group on Polio Eradication in Pakistan Islamabad, Pakistan 30 November – 1 December 2017 Acronyms AFP Acute Flaccid Paralysis bOPV Bivalent Oral Polio Vaccine CBV Community-Based Vaccination CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cVDPV2 Circulating Vaccine Derived Polio Virus Type 2 DPCR District Polio Control Room ES Environmental Sample EOC Emergency Operating Centers EV Entero-Virus FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FCVs Female Community Vaccinators GB Gilgit Baltistan GPEI Global Polio Eradication Initiative HRMP High-Risk Mobile Populations IPV Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine KP Khyber Pakhtunkhwa LEAs Law Enforcing Agents LPUCs Low Performing Union Councils LQAS Lot Quality Assurance Sampling mOPV Monovalent Oral Polio Vaccine NEOC National Emergency Operation Center NID National Immunization Day NGO Non-Governmental Organization NPAFP Non-Polio Acute Flaccid Paralysis PCM Post Campaign Monitoring PC1 Planning Commission 1 PEOC Provincial Emergency Operation Center RI Routine Immunization RSP Religious Support Persons SIA Supplementary Immunization Activity SOP Standard Operating Procedure TAG Technical Advisory Group UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund VDPV Vaccine Derived Polio Virus WHO World Health Organization WPV Wild Polio Virus 1 Table of Contents Acronyms 1 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Progress 11 Pakistan Program ...........................................................................................................................................................