HISTORY of BARBERSHOP Compiled by David Wright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Educator's Guide & Songbook

MUSIC EDUCATOR’S GUIDE & SONGBOOKIncludes: Barbershop Harmony Teaching Guide, Seven RoyaltyFree Songs, Barbershop Tags, and Accompanying Learning CD 2014 SPEBSQSA, Inc. 110 7th Ave. No., Nashville, TN 37203-3704, USA. Tel. (800) 876-7464 Permission granted to reproduce for personal and educational use only. Commercial copying, hiring, and lending is prohibited. www.barbershop.org #209532 Dear Music Educator: Thank you for your interest in Barbershop Harmony—one of the truly American musical art foorms! I think you will be surprised at the depth of instructional material and opportunities the Barbershop Harmony Society offers. More importantly, you’ll be pleased with the way your students accept this musical style. This guide contains a significant amount of information aboutt the barbershop style, as well as many helpful suggestions on how to teach it to your students. The songs included in this guide are an introduction to the barbershop style and include a part-predominant learning CD, all of which may be copied at no extra charge. For more barbershop music, our Harmony Marketplace offers thousands of barbershop arrangements, including PDF and mp3 demos, at www.barbershop.org/arrangementts. Songbooks, manuals, part-predominant learning CDs, educational videos and DVDs, merchandise, and more can be found at www.harmonymarketplace.com. For those who are not familiar with the Society or if you would like further information, please feel free to contact us at 1-800-876-SING or at [email protected]. Thanks again for your interest in the -

1St First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern

1st First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern. arr. Ozzie Westley (1944) BPC The Barberpole Cat Program and Song Book. (1987) BB1 Barber Shop Ballads: a Book of Close Harmony. ed. Sigmund Spaeth (1925) BB2 Barber Shop Ballads and How to Sing Them. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1940) CBB Barber Shop Ballads. (Cole's Universal Library; CUL no. 2) arr. Ozzie Westley (1943?) BC Barber Shop Classics ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1946) BH Barber Shop Harmony: a Collection of New and Old Favorites For Male Quartets. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1942) BM1 Barber Shop Memories, No. 1, arr. Hugo Frey (1949) BM2 Barber Shop Memories, No. 2, arr. Hugo Frey (1951) BM3 Barber Shop Memories, No. 3, arr, Hugo Frey (1975) BP1 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 1. (1946) BP2 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 2. (1952) BP Barbershop Potpourri. (1985) BSQU Barber Shop Quartet Unforgettables, John L. Haag (1972) BSF Barber Shop Song Fest Folio. arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1948) BSS Barber Shop Songs and "Swipes." arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1946) BSS2 Barber Shop Souvenirs, for Male Quartets. New York: M. Witmark (1952) BOB The Best of Barbershop. (1986) BBB Bourne Barbershop Blockbusters (1970) BB Bourne Best Barbershop (1970) CH Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle (1936) CHR Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle. Revised (1941) CH1 Close Harmony: Male Quartets, Ballads and Funnies with Barber Shop Chords. arr. George Shackley (1925) CHB "Close Harmony" Ballads, for Male Quartets. (1952) CHS Close Harmony Songs (Sacred-Secular-Spirituals - arr. -

Equity News Summer 2019

SUMMER 2019 | VOLUME 104 | ISSUE 3 ACTORS’ EQUITY ASSOCIATION Equity NEWS A CENTURY OF SOLIDARITY CELEBRATING THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE VERY FIRST EQUITY STRIKE EquityDIRECTORY EASTERN REGION WESTERN REGION BUSINESS THEATRE Kaitlyn Hoffman [email protected], x322 SPECIAL APPEARANCE, GUEST AND DINNER THEATRE ARTIST Philip Ring [email protected], x106 CABARET Kaitlyn Hoffman [email protected], x322 WITHIN LA - 99 SEAT Albert Geana-Bastare [email protected], x118 CASINO Doria Montfort [email protected], x334 TYA, STOCK, LOA TO COST & LOA TO WCLO Christa Jackson [email protected], x129 DINNER THEATRE Gary Dimon [email protected], x414 SPT, HAT Gwen Meno [email protected], x110 DINNER THEATRE ARTIST Austin Ruffer [email protected], x307 LORT Ethan Schwartz [email protected], x150 DISNEY WORLD Donna-Lynne Dalton [email protected], x604 Buckly Stephens [email protected], x602 LOA TO LORT Lyn Moon [email protected], x119 GUEST ARTIST Austin Ruffer [email protected], x307 CONTRACTS WITHIN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA Ethan Schwartz [email protected], x150 LABS/WORKSHOPS Corey Jenkins [email protected], x325 CONTRACTS WITHIN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Albert Geana-Bastare [email protected], x118 LOA-NYC Raymond Morales [email protected], x314 CONTRACTS WITHIN TEXAS & UTAH Christa Jackson [email protected], x129 LOA-PP Timmary Hammett [email protected], x376 Gary Dimon [email protected], x414 CONTRACTS -

Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression

American Music in the 20th Century 6 Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression Background: The United States in 1900-1929 In 1920 in the US - Average annual income = $1,100 - Average purchase price of a house = $4,000 - A year's tuition at Harvard University = $200 - Average price of a car = $600 - A gallon of gas = 20 cents - A loaf of Bread = 20 cents Between 1900 and the October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression, the United States population grew By 47 million citizens (from 76 million to 123 million). Guided by the vision of presidents Theodore Roosevelt1 and William Taft,2 the US 1) began exerting greater political influence in North America and the Caribbean.3 2) completed the Panama Canal4—making it much faster and cheaper to ship its goods around the world. 3) entered its "Progressive Era" by a) passing anti-trust laws to Break up corporate monopolies, b) abolishing child labor in favor of federally-funded puBlic education, and c) initiating the first federal oversight of food and drug quality. 4) grew to 48 states coast-to-coast (1912). 5) ratified the 16th Amendment—estaBlishing a federal income tax (1913). In addition, by 1901, the Lucas brothers had developed a reliaBle process to extract crude oil from underground, which soon massively increased the worldwide supply of oil while significantly lowering its price. This turned the US into the leader of the new energy technology for the next 60 years, and opened the possibility for numerous new oil-reliant inventions. -

Inciting the Rank and File: the Impact of Actors' Equity and Labor Strike

Inciting the Rank and File: The Impact of Actors’ Equity and Labor Strike Rachel Shane, PhD, University of Kentucky Abstract Stage actors have long been an integral element of the cultural community in the United States. From vaudeville to the Broadway stage, actors have carved a niche for themselves in the theatrical landscape of this country. Actors are both artists and workers within the theatrical industry. As the latter, actors are members of the labor movement and engage in traditional organized labor activities. This article explores why the members of Actors’ Equity Association have been motivated to strike against theatrical producers and reveals organizational weaknesses inherent when artists join the labor movement. Keywords Actors’ Equity Association, actors’ strike, cultural unions, labor in the arts Address correspondence to Rachel Shane, PhD, Director, Arts Administration Program, University of Kentucky, 111 Fine Arts Building, Lexington, KY 40506-0022. Telephone: 859.257.7717. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction “It is merely a question how far each actor is ready to be a hero in the fight.” -- Actor Richard Mansfield wrote in The World , December 2, 1897 of gaining rights for stage actors Stage actors have long been an integral element of the cultural community in the United States. From vaudeville to the Figure 1. Actor Richard Mansfield, 1907. Photo Credit: Broadway stage, actors have carved a niche for themselves in the Wikipedia. theatrical landscape of this country. Thus, over the years, hundreds of books have been published discussing the intricacies of the acting business, with most including a chapter or so on how to join an actors’ union. -

National Conference on Mass. Transit Crime and Vandali.Sm Compendium of Proceedings

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. n co--~P7 National Conference on Mass. Transit Crime and Vandali.sm Compendium of Proceedings Conducted by T~he New York State Senate Committee on Transportation October 20-24, 1980 rtment SENATOR JOHN D. CAEMMERER, CHAIRMAN )ortation Honorable MacNeil Mitchell, Project Director i/lass )rtation ~tration ansportation ~t The National Conference on Mass Transit Crime and Vandalism and the publication of this Compendium of the Proceedings of the Conference were made possible by a grant from the United States Department of Transportation, Urban Mass Transportation Administration, Office of Transportation Management. Grateful acknowledgement is extended to Dr. Brian J. Cudahy and Mr. Marvin Futrell of that agency for their constructive services with respect to the funding of this grant. Gratitude is extended to the New York State Senate for assistance provided through the cooperation of the Honorable Warren M. Anderson, Senate Majority Leader; Dr. Roger C. Thompson, Secretary of the Senate; Dr. Stephen F. Sloan, Director of the Senate Research Service. Also our appreciation goes to Dr. Leonard M. Cutler, Senate Grants Officer and Liaison to the Steering Committee. Acknowledgement is made to the members of the Steering Committee and the Reso- lutions Committee, whose diligent efforts and assistance were most instrumental in making the Conference a success. Particular thanks and appreciation goes to Bert'J. Cunningham, Director of Public Affairs for the Senate Committee on Transportation, for his work in publicizing the Conference and preparing the photographic pages included in the Compendium. Special appreciation for the preparation of this document is extended to the Program Coordinators for the Conference, Carey S. -

Enrichment Programs Keep Seniors Engaged After Retirement

Enrichment programs keep seniors engaged after retirement Updated March 25, 2017 9:53 AM By Kay Blough Special to Newsday Reprints + - PEIR member Marvin Schiffman of Long Beach shows off a card that he created in recognition of the group's 40th anniversary. Photo Credit: Barry Sloan ADVERTISEMENT | ADVERTISE ON NEWSDAY HIGHLIGHTS ▪ Hofstra University running Personal Enrichment In Retirement ▪ Peer-to-peer presentations, social activities keep members active Pithy anecdotes about William F. Buckley Jr. drew several rounds of chuckles during a lecture about the late conservative author and TV host, presented recently to a group of retirees at Hofstra University. The speaker, Al Drattell, 84, of Floral Park, shared a firsthand story from when he was a reporter assigned to cover a Buckley address: A court stenographer was taking notes, Drattell said. “She interrupted his speech: ‘Mr. Buckley, how do you spell that word,’ she asked. He spelled it and went on with his speech,” Drattell said. “And when he was asked what would happen if he won when he ran for mayor of New York City in 1965, he said, ‘Demand a recount.’ In his own way, he was very humorous.” (Buckley lost that race to John Lindsay, pulling 13 percent of the vote.) Most Popular • Kebab spot takes over hidden LI eatery • Daughter upset at her advance inheritance • New LI Shake Shack sets opening date • East End Restaurant Week starts today • Citi Field food: Mets unveil what’s new for 2017 Drattell’s presentation to about 100 members of PEIR, which stands for Personal Enrichment In Retirement, followed a talk about actor Henry Fonda — part of the group’s Great American Screen Legends series, presented by Jacki Schwartz, 72, of Oceanside, who, like Drattell, is a member of PEIR. -

John J. Marchi Papers

John J. Marchi Papers PM-1 Volume: 65 linear feet • Biographical Note • Chronology • Scope and Content • Series Descriptions • Box & Folder List Biographical Note John J. Marchi, the son of Louis and Alina Marchi, was born on May 20, 1921, in Staten Island, New York. He graduated from Manhattan College with first honors in 1942, later receiving a Juris Doctor from St. John’s University School of Law and Doctor of Judicial Science from Brooklyn Law School in 1953. He engaged in the general practice of law with offices on Staten Island and has lectured extensively to Italian jurists at the request of the State Department. Marchi served in the Coast Guard and Navy during World War II and was on combat duty in the Atlantic and Pacific theatres of war. Marchi also served as a Commander in the Active Reserve after the war, retiring from the service in 1982. John J. Marchi was first elected to the New York State Senate in the 1956 General Election. As a Senator, he quickly rose to influential Senate positions through the chairmanship of many standing and joint committees, including Chairman of the Senate Standing Committee on the City of New York. In 1966, he was elected as a Delegate to the Constitutional Convention and chaired the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Constitutional Issues. That same year, Senator Marchi was named Chairman of the New York State Joint Legislative Committee on Interstate Cooperation, the oldest joint legislative committee in the Legislature. Other senior state government leadership positions followed, and this focus on state government relations and the City of New York permeated Senator Marchi’s career for the next few decades. -

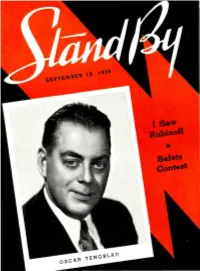

Stand by 360912.Pdf

SOME TIMEL Y CRITICISM Timely Comments but we have had the pleasure of like We'll Try It wise enjoying your good messages Do you suppose you could get that Dear Mr. Page: I was indeed very while on our way or returning from much interested in the comments you Florida. To say that your whole serv Stand By camera busy and get some made on August 24 over the radio ice is first-class in every respect is pictures of those newly-married cou concerning the housing of the Junior expressing it very mildly indeed. More ples such as the Racherbaumers, But Department at the Illinois State Fair. power to you !-D. A. Stoker, Chicago. trams and Blacks, and others who The Junior Department has grown may have marched to the altar before tremendously during the past five this card reaches you? You have no years and the general manager has idea how much we'd like to see them, recognized the problem of a suitable so please hurry on and print some if place to house the livestock for this Roy an Actor you can.-Ruth Raether, Lake Forest, Ill. department. This year, of course, Dear Marjorie Gibson: Only a few conditions were unusually bad due to lines from a Fanfare friend to let you ( Attention, you newlyweds: Let the two storms which visited the fair know that the interview you had last this letter be your notice that Stand grounds on Sa turday evening and Saturday with Roy Anderson was one By readers demand some bride and again on Wednesday evening. -

Preservation January 2013

The Official Publication of the Barbershop Harmony Society’s Historical Archives Volume 4, No. 1 Living In The Past - And Proud Of It! January 2013 Here’sHere’s ToTo TheThe LosersLosers 139th Street Quartet / Bank Street / Center Stage / Four Rascals / Metropolis / Nighthawks / Pacificaires / Playtonics / Riptide / Roaring 20s / Saturday Evening Post / Sundowners / Vagabonds In This Issue Pages Here’s To The Losers 13-50 Don Beinema 1921-2013 50 Victoria Leigh Soto 3 New York Treasure Hunt 5-6 75 Year Logo Has A Secret 4 SeeSee PagePage 1313 Flat Foot Four Footage Found 6 All articles herein - unless otherwise credited - were written by the editor 2 Volume 4, No. 1 January 2013 Published by the Society Archives Committee of the Barbershop Harmony Society for all those interested in preserving, promoting and educating others as to the rich history of the Barbershop music genre and the organization of men that love it. Society Archives Committee Grady Kerr - Texas (Chairman) Bob Sutton - Virginia Steve D'Ambrosio - Tennessee Bob Davenport - Tennessee Bob Coant - New York Ann McAlexander - Indianapolis, IN Touché Win Crowns Patty Leveille - Tennessee (BHS Staff Liaison) Congratulations to the new 2013 Society Historian / Editor / Layout International Queens of Harmony, Touché - Grady Kerr Patty Cobb Baker, Gina Baker, Jan Anton [email protected] and Kim McCormic. th In November, about 6,000 attended the 66 Proofreaders & Fact Checkers Bob Sutton, Ann McAlexander & Matthew Beals annual Sweet Adeline International With welcomed assists by Leo Larivee Convention in Denver, Colorado. More than 65 quartets and 40 choruses competed in five contests over the course of the week. -

A General History of the Burr Family, 1902

historyAoftheBurrfamily general Todd BurrCharles A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE BURR FAMILY WITH A GENEALOGICAL RECORD FROM 1193 TO 1902 BY CHARLES BURR TODD AUTHOB OF "LIFE AND LETTERS OF JOBL BARLOW," " STORY OF THB CITY OF NEW YORK," "STORY OF WASHINGTON,'' ETC. "tyc mis deserves to be remembered by posterity, vebo treasures up and preserves tbe bistort of bis ancestors."— Edmund Burkb. FOURTH EDITION PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR BY <f(jt Jtnuhtrboclur $«88 NEW YORK 1902 COPYRIGHT, 1878 BY CHARLES BURR TODD COPYRIGHT, 190a »Y CHARLES BURR TODD JUN 19 1941 89. / - CONTENTS Preface . ...... Preface to the Fourth Edition The Name . ...... Introduction ...... The Burres of England ..... The Author's Researches in England . PART I HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL Jehue Burr ....... Jehue Burr, Jr. ...... Major John Burr ...... Judge Peter Burr ...... Col. John Burr ...... Col. Andrew Burr ...... Rev. Aaron Burr ...... Thaddeus Burr ...... Col. Aaron Burr ...... Theodosia Burr Alston ..... PART II GENEALOGY Fairfield Branch . ..... The Gould Family ...... Hartford Branch ...... Dorchester Branch ..... New Jersey Branch ..... Appendices ....... Index ........ iii PART I. HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL PREFACE. HERE are people in our time who treat the inquiries of the genealogist with indifference, and even with contempt. His researches seem to them a waste of time and energy. Interest in ancestors, love of family and kindred, those subtle questions of race, origin, even of life itself, which they involve, are quite beyond their com prehension. They live only in the present, care nothing for the past and little for the future; for " he who cares not whence he cometh, cares not whither he goeth." When such persons are approached with questions of ancestry, they retire to their stronghold of apathy; and the querist learns, without diffi culty, that whether their ancestors were vile or illustrious, virtuous or vicious, or whether, indeed, they ever had any, is to them a matter of supreme indifference. -

The Orange Spiel Page 1 July 2018

The Orange Spiel Page 1 July 2018 Volume 38 Issue 7 July 2018 We meet at 7:00 most Thursdays at Shepherd of the Woods Lutheran, 7860 Southside Blvd, Jacksonville, FL Guests always welcome Call 355-SING No Experience Necessary WHAT'S INSIDE SOCIETY BOARD ANNOUNCES Title Page NEXT STEP TOWARD Society Board Announces Next Step 1,3 EVERYONE IN HARMONY Editorial 2 Barbershop History Questions 52 3 by Skipp Kropp Chapter Eternal 4-5 from barbershop.org Chapter Eternal 6 Stop Singing Rehearsal Sabotage 6-7 he Barbershop Harmony Society believes that Chapter Quartets 7 what we offer – the experience of singing to- Caribbean Gold Cruise 7 gether in harmony – is meaningful to all peo- Free Your Voice 8 T ple, and should therefore be accessible to peo- Free Singing Tips 8 ple in all combinations. Since the announcement of the A Better Way To Teach Complex Skills 9-11 Strategic Vision last June, the Society Board and staff 33 Most Effective Singing Tips 11 leadership have been involved in ongoing discussions Barbershop History Answers 52 11 about the best way to achieve the vision of Everyone Magic Choral Trick #377 And #378 12 in Harmony. Today, we are thrilled to announce our Singing With Good Posture 13-14 next step in the realization of that vision. Quartet Corner 15 Chapter Member Stats 15 Effective immediately, membership in the Barbershop Board Minute Summary 16 Harmony Society is open to EVERYONE. Beginning 2018 Hall Of Fame Inductees 16 today, we welcome women to join the Barbershop Upcoming Schedules 17 Harmony Society as members.