Measuring the Quality and Safety Outcomes of Nursing Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Responses of Flight Nurses to Catastrophic Events Gene L

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Masters Theses Graduate Research and Creative Practice 8-2004 Responses of Flight Nurses to Catastrophic Events Gene L. Olsen Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses Part of the Nursing Commons Recommended Citation Olsen, Gene L., "Responses of Flight Nurses to Catastrophic Events" (2004). Masters Theses. 544. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/544 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESPONSES OF FLIGHT NURSES TO CATASTROPHIC EVENTS By Gene L. Olsen A THESIS Submitted to Grand Valley State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE INlSHLfRlSINCI Kirkhof College of Nursing 2004 Thesis Committee Members Linda D. Scott, PhD, RN Andrea C. Bostrom, PhD, APRN, BC Mark J. Greenwood, DO, JD, FACEP Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. RESPONSES ()FI?IJ[C}E[I'lSnjqRJSIïS TO (:ATjtSTltOPHK:ITVEIfrS (jo ie L,. ()lser^ ISSÜST, Itf4,<:3FItFT,]3A/IT-]P August, 2004 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT itiüsi'CMstsiiS ()Fi^Li(jïiTr]snLni!SE:s ix) (i/iT^ALST^RjcwpirrczisT/iasri's By GeneL. Olsen, BSN, RN, CFRN, EMT-P The purpose of this study was to examine for the presence of symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a sample of flight nurses. -

Nursing in the Military the Profession of Alleviating the Suffering Of

Nursing in the Military The profession of alleviating the suffering of wounded and dying soldiers is as old as warfare itself. Our modern definition of nursing however started with Florence Nightingale on October 21, 1854 during the Crimean War when Nightingale together with she and a contingent of 38 volunteer women were dispatched to Turkey to the aid of wounded British soldiers. Nightingale¶s work later inspired nurses in the American Civil War, during which time, more than 5,000 women served as nurses on the battlefronts. With their contribution, they and their service helped to pave the way for women in professional medicine after the war. The history of women in the military began with the U.S. Army Nurse Corps in 1901. Duty Military nurses perform all the duties of a traditional nurse both during but are times of war and peace. They are also usually entrusted with a wider range of responsibilities than nurses in a civilian environment. In fact, a military nurse can be classified as active duty, reserve, or hired as a civilian employee. The tour of duty for an active or reserve nurse serving in the military requires a long-term commitment. It is common for military nurses to be sent abroad or into service at a combat hospital. Conversely, for civilian employees, the length of time depends on the contract. Ideally, active and reserve duty nurses in the military require experience in critical care, operating room, and trauma. Most are registered nurses with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree and enter into service as officers. -

The Value of Evidence-Based Practice in Military Nursing

MILITARY MEDICINE, 185, S2:4, 2020 The Value of Evidence-Based Practice in Military Nursing COL Melissa Hoffman, ANC* ; CAPT Debra Roy, NC, USN† ; Col Deedra Zabokrtsky, USAF, NC‡ ; Col Jennifer Hatzfeld, USAF, NC§ In an unpredictable and complex global environment where lished literature for the best evidence, working with a team our military force must remain globally engaged and adaptive, to synthesize the literature, and implementing a policy or maintaining the readiness of the force is essential. Within practice change based on the evidence. These are not skills the military health system (MHS), the focus is on quality that are unique to the military but are an important part of Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/milmed/article/185/Supplement_2/4/5835926 by guest on 27 September 2021 health care for our beneficiaries, lower cost, and clinical nursing practice. Nurses with advanced nursing degrees have skills sustainment.1 Those goals support our overall mission an additional 11 competencies that reflect their additional of generating a readily deployable force with a supporting responsibility to provide evidence-based care and the ability medical force ready to deliver health care anywhere and at any to independently evaluate and synthesize evidence.6 time. Evidence-based practice (EBP) provides an important Regardless of educational level, improvement of clinical tool for our health care professionals to maintain a readiness knowledge and processes through EBP is a daily occurrence focus, develop and maintain clinical skills, and provide care across military health care and is led by clinical staff nurses, that is relevant to both the military and civilian health care clinical nurse specialists, nurse scientists, and many other communities. -

Nursing Leaders in the Military Serving As Faculty

The Voice for Nursing Education Nursing Leaders in the Military Serving as Faculty A Toolkit For Nurse Faculty/Staff Preparing Military Nurse Officers For An Effective Second Career Into Nursing Education September 2018 Authors Myrna L. Armstrong, EdD, RN, ANEF, FAAN Nursing Consultant and Professor Emerita Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Colonel (R), ANC [email protected] Patricia Allen, EdD, RN, CNE, ANEF, FAAN Professor and Director, Nursing Education Track Distinguished University Professor Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center [email protected] Donna Lake, PhD, RN, NEA-BC Clinical Associate Professor East Carolina University College of Nursing Colonel, USAF NC (R) [email protected] The authors of this toolkit, titled A Toolkit for Nurse Faculty Preparing Military Nurse Officers for an Effective Second Career in Nursing Education, extend permission to the National League for Nursing (NLN) to post it on the NLN website. The authors also acknowledge this document will be open access; the intent is for users to adapt the toolkit for use in a variety of academ- ic and practice institutions. Users are asked to include in the citation of the source that the document was retrieved on the NLN website. This publication is dedicated to all of the men and women who have served in the United States military providing care to America’s sons and daughters. Toolkit Objectives Upon completion of this toolkit, the nurse educator will be able to: › Describe military nurse competencies transferable to the nurse educator role. › Recognize cultural differences between the Military Nurse Officer (MNO) and the academic nurse educator. -

The Challenges and Psychological Impact of Delivering Nursing Care Within a War Zone

The Challenges and Psychological Impact of Delivering Nursing Care within a War Zone Item Type Article Authors Finnegan, Alan; Lauder, William; McKenna, Hugh Citation Finnegan, A., Lauder, W., & McKenna, H. (2016). The challenges and psychological impact of delivering nursing care within a war zone. Nursing Outlook, DOI 10.1016/j.outlook.2016.05.005 Publisher Elsevier Journal Nursing Outlook Download date 24/09/2021 15:01:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/617614 The Challenges and Psychological Impact of Delivering Nursing Care within a War Zone Abstract Background. Between 2001 and 2014, British military nurses served in Afghanistan caring for both Service personnel and local nationals of all ages. However, there have been few research studies assessing the psychological impact of delivering nursing care in a War Zone hospital. Purpose. To explore the challenges and psychological stressors facing military nurses in undertaking their operational role. Method. A Constructivist Grounded Theory was utilised. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 18 British Armed Forces nurses at Camp Bastion Hospital, Afghanistan, in June – July 2013. Discussion. Military nurses faced prolonged periods of caring for seriously injured poly trauma casualties of all ages, and there were associated distressing psychological effects and prolonged periods of adjustment on returning home. Caring for children was a particular concern. The factors that caused stress, both on deployment and returning home, along with measures to address these issues such as time for rest and exercise, can change rapidly in response to the dynamic flux in clinical intensity common within the deployable environment. Conclusion. Clinical training, a good command structure, the requirement for rest, recuperation, exercise and diet were important in reducing psychological stress within a War Zone. -

Countries Where Anesthesia Is Administered by Nurses Lt Col MAURA S

Countries where anesthesia is administered by nurses Lt Col MAURA S. McAULIFFE, CRNA, PhD Rockville, Maryland BEVERLEY HENRY, RN, PhD, FAAN Chicago, Illinois Introduction Nurse anesthetists make significant In many countries anesthesia is administered pri- contributionsto healthcare worldwide. A marily by nurses. Yet few, including many in nurs- little known fact is that, in many countries ing, are aware of the major contribution to health of the world, nearly all anesthesiais that nurses, functioning as anesthetists, make. Even provided by nurses. This international some history books overlook nurses in anesthesia, survey, in five languages, was done to provide and little has been written about the education, information about nurse anesthesiacare practice, and legal regulation of nurse anesthetists delivered in countries in the regions of the worldwide. world designated by the World Health Two significant occurrences provided the im- Organization. petus for this study. First, in 1978, the World PhaseI, reported here, of a three-phase Health Organization (WHO) proclaimed its goal project, determined that nurses administer of health for all by the year 2000, in which nurses anesthesia in at least 107 of the world's nearly are viewed as major contributors and anesthesia as 200 countries. They administeranesthesia in an essential service. Second, the idea for an inter- developed, developing, and least developed national professional organization took root countries, as well as in all regions of the through which nurse anesthetists from all coun- world. A goal of disseminatingdata in this tries could collaborate, culminating, in 1989, in article is to further validate these 1992-1994 the formation of the International Federation of study findings. -

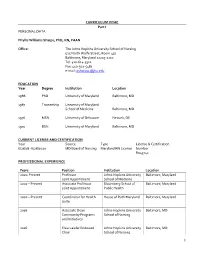

CURRICULUM VITAE Part I PERSONAL DATA Phyllis Williams

CURRICULUM VITAE Part I PERSONAL DATA Phyllis Williams Sharps, PhD, RN, FAAN Office: The Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing 525 North Wolfe Street, Room 437 Baltimore, Maryland 21205-2110 Tel: 410-614-5312 Fax: 410-502-5481 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Year Degree Institution Location 1988 PhD University of Maryland Baltimore, MD 1987 Traineeship University of Maryland School of Medicine Baltimore, MD 1976 MSN University of Delaware Newark, DE 1970 BSN University of Maryland Baltimore, MD CURRENT LICENSE AND CERTIFICATION Year Source Type License & Certification 6/28/18 -6/28/2020 MD Board of Nursing Maryland RN License Number R043742 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Years Position Institution Location 2020-Present Professor Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland Joint Appointment School of Medicine 2002 – Present Associate Professor Bloomberg School of Baltimore, Maryland Joint Appointment Public Health 2002 – Present Coordinator for Health House of Ruth Maryland Baltimore, Maryland Suite 2016 Associate Dean Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD Community Programs School of Nursing and Initiatives 2016 Elsie Lawler Endowed Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD Chair School of Nursing 1 2011 Associate Dean Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD Community and Global School of Nursing Programs 2007- 2011 Department Chair Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD School of Nursing 2007 Professor Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD School of Nursing 2001 – 2007 Associate Professor Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland School of Nursing 2002-2006 Director, Master’s Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD Program School of Nursing 2000 – 2001 Director George Washington Washington, D.C. University, School of Public Health & Health Services 1998 – 2000 Associate Research George Washington Washington, D.C. -

Scientific Programme Wednesday, 26. June 2019 Student Assembly

International Council of Nurses Congress 2019, 27 June - 1 July 2019, Marina Bay Sands, Singapore Scientific Programme Wednesday, 26. June 2019 Side meeting 08:30 - 17:00 Academia Student Assembly The ICN Congress Nursing Student Assembly will be held on Wednesday, 26 June from 09:00 to 17:00 at the Academia at the Singapore General Hospital. Registration will begin at 08:30. Simultaneous interpretation will be provided in English, French and Spanish. The Assembly provides nursing students the opportunity to connect, explore and collaborate on priority issues. Registration to the event 08:30 - 09:00 Welcome, Presentation and Introduction by the Singapore Nurses 09:00 - 09:10 Association, ICN Ice breaker 09:10 - 09:30 ICN – The Global Voice of Nursing 09:30 - 09:43 Nursing Now 09:43 - 09:56 State of the World’s Nursing 09:56 - 10:10 Care To Go Beyond 10:10 - 10:40 Break 10:40 - 11:00 Lost in Transition – Newly qualified Registered Nurses and their 11:00 - 11:20 transition to practice journey Developing the next generation – Lessons learnt from the Emerging 11:20 - 11:50 Nurse Leader Programme Hashtags & Healthcare: Social media and its relationship to mental 11:50 - 12:20 health Q&A 12:20 - 12:40 The future of student engagement at ICN 12:40 - 13:00 Lunch 13:00 - 14:00 Group Work (Breakout rooms) 14:00 - 15:30 Break 15:30 - 15:45 Reports of the group work 15:45 - 16:30 Conclusions of the Assembly 16:30 - 16:45 Page 1 / 168 International Council of Nurses Congress 2019, 27 June - 1 July 2019, Marina Bay Sands, Singapore Scientific Programme Thursday, 27. -

Characteristics and Values of a British Military Nurse. International Implications of War Zone Qualitative Research

Nurse Education Today 36 (2016) 86–95 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Nurse Education Today journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/nedt Characteristics and values of a British military nurse. International implications of War Zone qualitative research Alan Finnegan a, Sara Finnegan b, Hugh McKenna c, Stephen McGhee d, Lynda Ricketts e, Kath McCourt f, Jem Warren g,MikeThomash a Department of Military Nursing, Royal Centre for Defence Medicine, ICT Centre, Birmingham Research Park, Vincent Drive, Birmingham B15 2SQ, United Kingdom b Eastham Group Practice, Treetops Primary Healthcare Centre, 47 Bridle Road, Bromborough Wirral, CH62 6EE, United Kingdom c Research & Innovation, University of Ulster, Shore Road, Newtownabbey, Co. Antrim, BT37 0QB, United Kingdom d University of South Florida, 12901 Bruce B. Downs Boulevard, Tampa, FL 33612-4476, United States e 4 Armoured Medical Regiment, New Normandy Barracks, Evelyn Woods Road, Aldershot, Hampshire GU11 2LZ, United Kingdom f Faculty of Health & Life Sciences University of Northumbria, E210, 2nd Floor Coach Lane Campus, West Benton, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE7 7XA, United Kingdom g Strategic Funding Office, University of Chester, Senate House CSH109, Parkgate Road, Chester CH1 4BJ, United Kingdom h University of Central Lancashire, Preston, Lancashire PR1 2HE, United Kingdom article info summary Article history: Background: Between 2001 and 2014, British military nurses served in Afghanistan caring for both Service Accepted 29 July 2015 personnel and local nationals of all ages. However, there have been few research studies assessing the effective- ness of the military nurses' operational role and no papers naming the core values and characteristics. This paper Keywords: is from the only qualitative nursing study completed during this period where data was collected in the War Military nursing Zone. -

Male Nurses' Experience of Gender Stereotyping Over the Past Five

Molloy College DigitalCommons@Molloy Theses & Dissertations 5-2019 Male Nurses’ Experience Of Gender Stereotyping Over The Past Five Decades: A Narrative Approach Michael W. Finnegan Molloy College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.molloy.edu/etd Part of the Nursing Commons This Dissertation has All Rights Reserved. DigitalCommons@Molloy Feedback Recommended Citation Finnegan, Michael W., "Male Nurses’ Experience Of Gender Stereotyping Over The Past Five Decades: A Narrative Approach" (2019). Theses & Dissertations. 76. https://digitalcommons.molloy.edu/etd/76 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Molloy. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Molloy. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Molloy College The Barbara H. Hagan School of Nursing PhD in Nursing Program MALE NURSES’ EXPERIENCE OF GENDER STEREOTYPING OVER THE PAST FIVE DECADES: A NARRATIVE APPROACH a dissertation by MICHAEL W. FINNEGAN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 © Copyright by MICHAEL W. FINNEGAN All Rights Reserved 2019 i Abstract Negative stereotyping of men in nursing has been a chronic problem that has a direct effect on males and detracts from efforts to recruit and retain them. At this time in American history (2018), traditionally male-dominated professions are making significant progress toward the goal of a gender-balanced workplace. However, the opposite is not true. Traditionally female-dominated professions are not attracting or appealing to men. In the nursing profession, the number of male nurses is relatively small and has remained relatively fixed over time. -

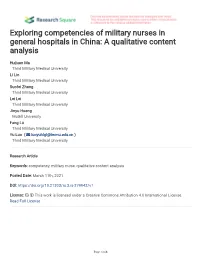

Exploring Competencies of Military Nurses in General Hospitals in China: a Qualitative Content Analysis

Exploring competencies of military nurses in general hospitals in China: A qualitative content analysis Huijuan Ma Third Military Medical University Li Lin Third Military Medical University Suofei Zhang Third Military Medical University Lei Lei Third Military Medical University Jinyu Huang McGill University Fang Lu Third Military Medical University Yu Luo ( [email protected] ) Third Military Medical University Research Article Keywords: competency, military nurse, qualitative content analysis Posted Date: March 11th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-279942/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/16 Abstract Background: Military nurses should possess the competency to provide quality care in both clinical and military nursing contexts. This study aimed to identify the competencies of military nurses in general hospitals. Methods: A qualitative design based on the content analysis approach was employed. We purposefully sampled and interviewed 21 nurses in general hospitals in China. Results: The data analysis revealed 40 competencies, which were categorised into four main categories according to the onion model. These categories were motive (mission commitment), traits (perseverance, exibility, etc.), self-identity of dual roles (obedience, empathy, etc.), as well as knowledge, skills and abilities (clinical and military nursing knowledge and skills, basic nursing ability, professional development ability, leadership and management ability). Conclusion: Existing knowledge of competencies of military nurses in general hospitals is limited. A detailed exploration of this topic can provide guidance for recruitment, competency assessment, and competency building. Background Competency is dened as a personal trait or set of habits that leads to more effective or superior job performance, and it has ve major components: knowledge, skills, self-concepts and values, traits, and motives [1, 2]. -

Evaluation of Basic Nursing Education Programme In

EVALUATION OF BASIC NURSING EDUCATION PROGRAMME IN NIGERIA BY ONWUCHEKWA EDNA JANUARY, 2016 i EVALUATION OF BASIC NURSING EDUCATION PROGRAMME IN NIGERIA BY ONWUCHEKWA EDNA (909003094) JANUARY, 2016 ii EVALUATION OF BASIC NURSING EDUCATION PROGRAMME IN NIGERIA BY ONWUCHEKWA EDNA (909003094) B.sc. Nursing Education, University of Ibadan M.Ed. (Curriculum Studies), University of Lagos A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCE EDUCATION, THE SCHOOL OF POST GRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE (Ph.D.) IN CURRICULUM THEORY JANUARY, 2016 iii iv DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the Almighty God, El-Shaddai, Adonai, Nissi and Ebenezer. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I would like to thank my first supervisor Prof. K.A. Adegoke, for his meticulous and insightful contributions. He painstakingly read through this research several times and made valuable suggestions. He is a resourceful researcher and a mentor. I wish to express my warm gratitude to Dr (Mrs) Rosita Igwe my second supervisor for her numerous corrections to improve the quality of this work, she is always there for us. I am highly indebted to Dr. (Mrs) N.R Ikonta for her calm and cheerful disposition, insightful contributions and the significant role she played towards my Ph.Dprogramme. I am most grateful to Prof. (Mrs) Opara, the Head of Department Arts and Social Sciences Education for her humility, simplicity and constructive criticism. She is always willing to help. God will surely bless her abundantly. I want to appreciate Dr. (Mrs) Maduekwe, the departmental post graduate Coordinator for her contributions towards the success of this study.