Danny Elfman's Masterclass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unknown Known by Errol Morris: Quebec Premiere at Docville Thursday, April 24, 8 P.M., Cinéma Excentris

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE DISTRIBUTION The Unknown Known by Errol Morris: Quebec premiere at Docville Thursday, April 24, 8 p.m., Cinéma Excentris Montreal, Thursday, April 10, 2014 – The Montreal International Documentary Festival (RIDM) is proud to present the Quebec premiere of The Unknown Known by Errol Morris, the fourth monthly Docville screening of 2014. Morris is the internationally acclaimed director of such films as The Fog of War and The Thin Blue Line. In 2003, Errol Morris won the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature for The Fog of War, in which former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara reflected on his career. A decade later, the filmmaker interviewed Donald Rumsfeld, who held the same position under George W. Bush. Armed with thousands of memos written by Rumsfeld during his long White House career (which began during the Nixon/Ford administration), Morris questions the controversial political figure on thorny topics like the invasion of Iraq under false pretences and the use of torture at Abu Ghraib. Staring down the camera without ever losing his aloof smile, Rumsfeld tackles every question with rhetorical poise as hypnotic as the film’s music, by Danny Elfman. Shown at the Venice, Telluride and Toronto festivals, The Unknown Known is a gripping verbal duel that leaves the historical truth more elusive than ever. THE UNKNOWN KNOWN Directed by Errol Morris. United States. 2013. 103 min. In English. Thursday, April 24, 8 p.m., Cinéma Excentris The film is distributed by Les Films Séville, an Entertainment One company. Trailer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9TcZ2‐sEb3o Online ticket purchase: https://excentris.ticketacces.net/fr/organisation/representations/index.cfm?EvenementID=511 Since 2012, the RIDM’s Docville series, presented on the last Thursday of every month, has given audiences the chance to see Montreal premieres of excellent documentaries that have enjoyed recent success at the world’s most prestigious festivals. -

The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor Lavey

The Rites of Lucifer On the altar of the Devil up is down, pleasure is pain, darkness is light, slavery is freedom, and madness is sanity. The Satanic ritual cham- ber is die ideal setting for the entertainment of unspoken thoughts or a veritable palace of perversity. Now one of the Devil's most devoted disciples gives a detailed account of all the traditional Satanic rituals. Here are the actual texts of such forbidden rites as the Black Mass and Satanic Baptisms for both adults and children. The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor LaVey The ultimate effect of shielding men from the effects of folly is to fill the world with fools. -Herbert Spencer - CONTENTS - INTRODUCTION 11 CONCERNING THE RITUALS 15 THE ORIGINAL PSYCHODRAMA-Le Messe Noir 31 L'AIR EPAIS-The Ceremony of the Stifling Air 54 THE SEVENTH SATANIC STATEMENT- Das Tierdrama 76 THE LAW OF THE TRAPEZOID-Die elektrischen Vorspiele 106 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN-Homage to Tchort 131 PILGRIMS OF THE AGE OF FIRE- The Statement of Shaitan 151 THE METAPHYSICS OF LOVECRAFT- The Ceremony of the Nine Angles and The Call to Cthulhu 173 THE SATANIC BAPTISMS-Adult Rite and Children's Ceremony 203 THE UNKNOWN KNOWN 219 The Satanic Rituals INTRODUCTION The rituals contained herein represent a degree of candor not usually found in a magical curriculum. They all have one thing in common-homage to the elements truly representative of the other side. The Devil and his works have long assumed many forms. Until recently, to Catholics, Protestants were devils. To Protes- tants, Catholics were devils. -

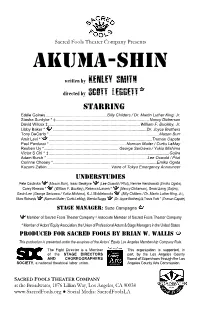

AKUMA-SHIN Is a Rumination on the Shadow, the Lurking Unknown of Nightmare

Sacred Fools Theater Company Presents Akuma- shin written by Kenley Smith directed by Scott Leggett Starring Eddie Goines.......................................................Billy Childers / Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Stasha Surdyke * ‡................................................................................... Nancy Dickerson David Wilcox ‡.................................................................................. William F. Buckley, Jr. Libby Baker * ...................................................................................Dr. Joyce Brothers Tony DeCarlo *.................................................................................................. Mason Burr Amir Levi * ............................................................................................Truman Capote Paul Parducci *.....................................................................Norman Mailer / Curtis LeMay Reuben Uy *.................................................................. George Serizawa / Yukio Mishima Victor S Chi * ‡........................................................................................................... Gojira Adam Burch * ..........................................................................................Lee Oswald / Pilot Corinne Chooey *............................................................................................Emiko Ogata Kazumi Zatkin......................................................... Voice of Tokyo Emergency Announcer Understudies Pete Caslavka (Mason Burr), -

Dive 010 - Sea Docs

Dive 010 - Sea Docs Our last collection of Sea Genre films focusing on the watery realms of The Soundtrack Zone may be classified as films in the Sea Documentary genre or, for short, Sea Docs. Two early examples of scores for a Sea Doc film were those composed by Paul J. Smith for two Walt Disney’s True-Life Adventures films: Beaver Valley (1950) and Prowlers of the Everglades (1953). A Disneyland LP (WDL-4011 – released in 1975) included the following tracks from those two films: Beaver Valley (7:15) - Beaver Valley Theme - Baby Ducks - Beaver Romance - Salmon Run – Otters Prowlers of the Everglades (4:09) - Alligators - Swamp Deluge - Otters And Gators LP In 1956, Walt Disney’s Disneyland WDL-4006 LP presented Paul J. Smith’s score for another True-Life Adventure film, Secrets of Life. One of the album’s suites, “Under The Sea And Along The Shore,” includes several underwater-related tracks: Decorator Crab, Jellyfish, Angler Fish, and Fiddler Crabs (04:21) LP Three years later, in 1959, Walt Disney released a short film titled Mysteries of the Deep (23:55). Three of these films – Beaver Valley, Prowlers of the Everglades, and Mysteries of the Deep are available on DVD (see DVD 1 photo below). Secrets of Life is included on DVD 2 (see photo below). DVD 1 DVD 2 Unfortunately none of the scores for these Walt Disney underwater-related films have been commercially issued on CD. Fortunately, the scores of many subsequent Sea Docs films have been released over the years on LP and/or CD. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

The Unknown Known

BERLINALE SPECIAL THE UNKNOWN KNOWN Errol Morris Über 10 000 Memos schrieb Donald Rumsfeld als Ratgeber von vier USA 2013 US-Präsidenten und Verteidigungsministern an seine Mitarbeiter und 102 Min. · DCP · Farbe · Dokumentarfilm Kollegen. Diese über Jahrzehnte aufgehobenen aufschlussreichen No- tizen bilden die Grundlage für die Annäherung an einen Mann, der die Regie Errol Morris US-amerikanische Außenpolitik und den sogenannten Krieg gegen Kamera Robert Chappell Schnitt Steven Hathaway den Terror entscheidend mitprägte. In einem neutralen Raum bittet Musik Danny Elfman der Filmemacher den umstrittenen Politiker, Platz zu nehmen und ver- Sound Design Skip Lievsay wickelt ihn mit scheinbar banalen Fragen in ein immer brisanter wer- Production Design Ted Bafaloukos, dendes Gespräch. Von Pearl Harbor über Vietnam bis zu 9/11 bezieht Jeremy Landman Geboren 1948 in Hewlett, New York. Studierte Rumsfeld Stellung zum Umgang der USA mit militärischen und po- Produzenten Errol Morris, Philosophie an der University of Wisconsin litischen Fehlern und Katastrophen. Robert Fernandez, Amanda Branson Gill in Madison, der Princeton University und der Mit diesem Film schlägt der Essay- und Dokumentarfilmer Errol Mor- Ausführende Produzenten Dirk Hoogstra, University of California in Berkeley. Außerdem ris ein weiteres Kapitel verdrängter US-Geschichte auf. In STANDARD Julian P. Hobbs, Molly Thompson, Cello bei Nadia Boulanger, bei der auch Philip Diane Weyermann, Jeff Skoll, Tom Quinn, Glass und Quincy Jones Unterricht nahmen. OPERATION PROCEDURE (Wettbewerb Berlinale, 2008) ergründete er die Vorgänge hinter den Folterfotos aus Abu Ghraib. Und schon einmal Jason Janego, Josh Braun, Celia Taylor, Drehte seit 1978 zahlreiche Dokumentarfilme, Angus Wall, Julia Sheehan die sich vorzugsweise mit wissenschaftlichen nahm er einen ehemaligen US-Verteidigungsminister, Robert S. -

February 2018 at BFI Southbank Events

BFI SOUTHBANK EVENTS LISTINGS FOR FEBRUARY 2018 PREVIEWS Catch the latest film and TV alongside Q&As and special events Preview: The Shape of Water USA 2017. Dir Guillermo del Toro. With Sally Hawkins, Michael Shannon, Doug Jones, Octavia Spencer. Digital. 123min. Courtesy of Twentieth Century Fox Sally Hawkins shines as Elisa, a curious woman rendered mute in a childhood accident, who is now working as a janitor in a research center in early 1960s Baltimore. Her comfortable, albeit lonely, routine is thrown when a newly-discovered humanoid sea creature is brought into the facility. Del Toro’s fascination with the creature features of the 50s is beautifully translated here into a supernatural romance with dark fairy tale flourishes. Tickets £15, concs £12 (Members pay £2 less) WED 7 FEB 20:30 NFT1 Preview: Dark River UK 2017. Dir Clio Barnard. With Ruth Wilson, Mark Stanley, Sean Bean. Digital. 89min. Courtesy of Arrow Films After the death of her father, Alice (Wilson) returns to her family farm for the first time in 15 years, with the intention to take over the failing business. Her alcoholic older brother Joe (Stanley) has other ideas though, and Alice’s return conjures up the family’s dark and dysfunctional past. Writer-director Clio Barnard’s new film, which premiered at the BFI London Film Festival, incorporates gothic landscapes and stunning performances. Tickets £15, concs £12 (Members pay £2 less) MON 12 FEB 20:30 NFT1 Preview: You Were Never Really Here + extended intro by director Lynne Ramsay UK 2017. Dir Lynne Ramsay. With Joaquin Phoenix, Ekaterina Samsonov, Alessandro Nivola. -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

The Great Documentaries II Instructor: Michael Fox Mondays, 12 Noon-1:30Pm, June 7-28, 2021 [email protected]

The Great Documentaries II Instructor: Michael Fox Mondays, 12 noon-1:30pm, June 7-28, 2021 [email protected] With nonfiction films entrenched as a genre of mainstream movie entertainment, we examine standouts of the contemporary documentary. The five-session lineup is comprised of a trio of films about recent historical events bookended by personal documentaries. This lecture and discussion class (students will view the films on their own prior to class) encompasses perennial issues such as the responsibility of the filmmaker to his/her subject, the slipperiness of truth, the tools of storytelling and the use of poetry and metaphor in nonfiction. Four of the films can be streamed for free (three on Kanopy, one on Hoopla) and the other can be rented from Amazon Prime and other platforms. All the films are probably available via Netflix’s DVD plan. The Great Documentaries II is a historical survey that follows and builds on Documentary Touchstones I and II, which I taught at OLLI a few years ago. I’ve appended a list of those films and more information at the end of the syllabus, if you have never seen them and wish to journey further back into the history of documentaries. Most of the titles are available to watch for free on YouTube, although the quality of the prints varies. June 7 Sherman’s March (1986, Ross McElwee, 158 min) Kanopy After his girlfriend leaves him, McElwee voyages along the original route followed by Gen. William Sherman. Rather than cutting a swath of destruction designed to force the Confederate South into submission, McElwee searches for love, camera in hand, “training his lens with phallic resolve on every accessible woman he meets.” Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, named one of the Top 20 docs of all time by the International Documentary Association, added to the Library of Congress National Film Registry in 2000.