Confidential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pengawasan Kualiti Alam Sekitar

PENGAWASAN KUALITI ALAM SEKITAR Pengawasan Kualiti Udara Terdapat 3 stesen pengawasan kualiti udara iaitu di Bakar Arang (Sungai Petani), Mergong (Alor Setar) dan Kuah (Langkawi). Program pengawasan kualiti udara dijalankan oleh pihak swasta iaitu ASMA Sdn. Bhd. Berdasarkan Indek Kualiti Udara (IPU) rujuk (Jadual 2.1), kualiti udara di Negeri Kedah mencatatkan status kualiti purata yang baik iaitu bacaan IPU kurang daripada 50 bagi kesemua stesen (Jadual 2.2). Jadual 2.1: Indek Pencemaran Udara IPU Status Kualiti Udara 0 – 50 Sihat 51 – 100 Sederhana Sihat 101 – 200 Tidak Sihat 201 – 300 Sangat Tidak sihat ≥ 300 Merbahaya Jadual 2.2: Indek Pencemaran Udara Mengikut Stesen Nama Stesen/Tahun 2010 2011 2012 2013 Bakar Arang, Sungai Petani 41 41 43 46 Mergong, Alor Setar 29 36 37 32 Kuah, Langkawi 31 32 35 37 16 PENGAWASAN KUALITI ALAM SEKITAR Lokasi Stesen Pengawasan Kualiti Udara Rajah 2.1 : Status Kualiti Udara Mengikut Stesen Pengawasan Udara 17 PENGAWASAN KUALITI ALAM SEKITAR Pengawasan Kualiti Air Sungai Status kualiti air sungai di nilai berdasarkan Indek Kualiti Air Negara rujuk (Jadual 2.3). Terdapat 5 lembangan sungai dan 31 stesen pengawasan kualiti air sungai rujuk (Jadual 2.4) dan program pengawasan kualiti air sungai dijalankan oleh pihak swasta iaitu ASMA Sdn. Bhd. Berdasarkan IKAN, 2 lembangan adalah berstatus baik manakala 3 lembangan berstatus sederhana tercemar seperti di Rajah 2.2. Jadual 2.3: Indeks Kualiti Air Negara (IKAN) IKAN Status 81 – 100 Bersih 60 – 80 Sederhana Tercemar 0 -59 Tercemar Rajah 2.2 : Status Kualiti Air Sungai Mengikut Lembangan 18 PENGAWASAN KUALITI ALAM SEKITAR Jadual 2.4: Stesen Pengawasan Kualiti Air Sungai Mengikut Lembangan Indek Bil. -

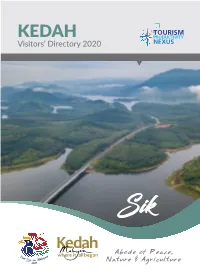

Visitors' Directory 2020

KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 Abode of Peace, Nature & Agriculture KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 KEDAH 2 Where you’ll find more than meets the mind... SEKAPUR SIREH JUNJUNG 4 Chief Minister of Kedah SEKAPUR SIREH KEDAH Kedah State Secretary State Executive Councilor Where you’ll find Champion, Tourism Productivity Nexus ABOUT TOURISM PRODUCTIVITY NEXUS (TPN) 12 more than meets the mind... WELCOME TO SIK 14 Map of Sik SIK ATTRACTIONS 16 Sri Lovely Organic Farm Lata Mengkuang Waterfalls Beris Lake Empangan Muda (Muda Dam) KEDA Resort Bendang Man Ulu Muda Eco Park Lata Lembu Forest Waterfall Sungai Viral Jeneri Hujan Lebat Forest Waterfall Lata Embun Forest Waterfall KEDAH CUISINE AND A CUPPA 22 Food Trails Passes to the Pasars 26 SIK EXPERIENCES IN GREAT PACKAGES 28 COMPANY LISTINGS PRODUCT LISTINGS 29 Livestock & Agriculture Operators Food Operators Craft Operators 34 ACCOMMODATION ESSENTIAL INFORMATION CONTENTS 36 Location & Transportation Getting Around Getting to Langkawi No place in the world has a combination of This is Kedah, the oldest existing kingdom in Useful Contact Numbers Tips for Visitors these features: a tranquil tropical paradise Southeast Asia. Essential Malay Phrases You’ll Need in Malaysia laced with idyllic islands and beaches framed Making Your Stay Nice - Local Etiquette and Advice by mystical hills and mountains, filled with Now Kedah invites the world to discover all Malaysia at a Glance natural and cultural wonders amidst vibrant her treasures from unique flora and fauna to KEDAH CALENDAR OF EVENTS 2020 cities or villages of verdant paddy fields, delicious dishes, from diverse experiences 46 all cradled in a civilisation based on proven in local markets and museums to the 48 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT history with archaeological site evidence coolest waterfalls and even crazy outdoor EMERGENCIES going back three millennia in an ancient adventures. -

Public Summary of Recertification Audit of Kedah Forest Management Unit for Forest Management Certification

PUBLIC SUMMARY OF RECERTIFICATION AUDIT OF KEDAH FOREST MANAGEMENT UNIT FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATION Certificate No : FMC 003 Date of Recertification Audit: 23-27 September 2012 Certification Body: SIRIM QAS International Sdn Bhd Block 4, SIRIM Complex 1, Persiaran Dato’ Menteri Section 2, P. O. Box 7035 40700 Shah Alam Selangor, MALAYSIA Tel: +60 3 5544 6400 +60 3 5544 6448 Fax: +60 3 5544 6763 Email: [email protected] Page 1 of 17 1. INTRODUCTION The Kedah Forest Management Unit (hereafter referred to as ‘the Kedah FMU’) was awarded the Certificate for Forest Management against the MC&I (2002) following the Stage 2 Audit that was conducted on 17 – 22 November 2009. Following the certification, the first surveillance audit was conducted on 1 - 4 November 2010, while the second surveillance audit on 14 - 17 November 2011. The recertification audit on the Kedah FMU was conducted from 23-27 September 2012. This was an audit to assess the continued overall compliance of the Kedah State Forestry Department (KSFD)’s forest management system and practices of the Permanent Reserved Forests (PRFs) within the Kedah FMU against the requirements of the Malaysian Criteria and Indicators for Forest Management Certification [MC&I (2002)]. In line with the transition plan from the use of MC&I (2002) to MC&I (Natural Forest), the recertification audit also included the MC&I (Natural Forest) in its audit scope. This recertification audit was conducted by a four-member team comprising Mr. Khairul Najwan Ahmad Jahari (Forester), Dr. Samsudin Musa (Forester), Prof Mohd Basri Hamzah (Forester) and Dr. -

2-D Resistivity Imaging of Buried Furnace at Sik, Kedah (Malaysia)

2-D Resistivity Imaging of Buried Furnace at Sik, Kedah (Malaysia) Dr. M.M. Nordiana Lecturer at Geophysics Section, School of Physics, 11800 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia e-mail: [email protected] Dr. Rosli Saad Senior Lecturer at Geophysics Section, School of Physics, 11800 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia e-mail:[email protected] Dr. Mokhtar Saidin Professor at Centre for Global Archeological Research Malaysia, 11800 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia e-mail:[email protected] ABSTRACT 2-D resistivity imaging is non-destructive method that becomes important tools for the scientific investigation of archaeological study. Kedah area has recently shown a great potential of archaeological findings. The main objective of the present work is to locate the extension of the buried furnace in the area of Padang Cicak, Sik, Kedah (Malaysia) using 2-D resistivity survey for shallow investigations. Resistivity data were collected using Pole-Dipole array with 0.5 m electrode spacing. Afterwards, the resistivity data were processed with 2-D inversion resistivity (Res2Dinv) software which includes smoothness constrained. The results revealed high resistivity zones with < 15 Ωm at depth ranging from 0.-1.5 m at the study area. Base on the archaeological evidence, the lower resistivity values indicate the interest anomaly for archaeological excavation. KEYWORDS: 2-D Resistivity, Archaeology, Buried, Furnace, Kedah. INTRODUCTION The geophysical study was conducted at Kampong Padang Cicak, Sik Kedah. It involves 2-D resistivity imaging. The objective of the study is to identify the extension of the furnace found at the area. In an attempt to non-invasively assess the number and extent of the excavation structures, 2-D resistivity was applied at that archaeological area. -

1970 Population Census of Peninsular Malaysia .02 Sample

1970 POPULATION CENSUS OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA .02 SAMPLE - MASTER FILE DATA DOCUMENTATION AND CODEBOOK 1970 POPULATION CENSUS OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA .02 SAMPLE - MASTER FILE CONTENTS Page TECHNICAL INFORMATION ON THE DATA TAPE 1 DESCRIPTION OF THE DATA FILE 2 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 1: HOUSEHOLD RECORD 4 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 2: PERSON RECORD (AGE BELOW 10) 5 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 3: PERSON RECORD (AGE 10 AND ABOVE) 6 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 1 7 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 2 15 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 3 24 APPENDICES: A.1: Household Form for Peninsular Malaysia, Census of Malaysia, 1970 (Form 4) 33 A.2: Individual Form for Peninsular Malaysia, Census of Malaysia, 1970 (Form 5) 34 B.1: List of State and District Codes 35 B.2: List of Codes of Local Authority (Cities and Towns) Codes within States and Districts for States 38 B.3: "Cartographic Frames for Peninsular Malaysia District Statistics, 1947-1982" by P.P. Courtenay and Kate K.Y. Van (Maps of Adminsitrative district boundaries for all postwar censuses). 70 C: Place of Previous Residence Codes 94 D: 1970 Population Census Occupational Classification 97 E: 1970 Population Census Industrial Classification 104 F: Chinese Age Conversion Table 110 G: Educational Equivalents 111 H: R. Chander, D.A. Fernadez and D. Johnson. 1976. "Malaysia: The 1970 Population and Housing Census." Pp. 117-131 in Lee-Jay Cho (ed.) Introduction to Censuses of Asia and the Pacific, 1970-1974. Honolulu, Hawaii: East-West Population Institute. -

On Kedah Forest Management Unit for Forest Management Certification (Natural Forest)

PUBLIC SUMMARY SURVEILLANCE 1 AUDIT (THIRD CYCLE) ON KEDAH FOREST MANAGEMENT UNIT FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATION (NATURAL FOREST) Certificate Number: FMC 0003 Date of First Certification: 9 June 2010 Audit Date: 7-10 November 2016 Date of Public Summary : 17 July 2017 Certification Body: SIRIM QAS International Sdn. Bhd. Block 4, SIRIM Complex No. 1, Persiaran Dato’ Menteri Section 2, 40700 Shah Alam Selangor MALAYSIA Tel : 60-3-5544 6400/5544 6448 Fax : 60-3 5544 6763 Website : www.sirim-qas.com.my SQAS/MSC/FOR/30-27a Issue 1 Rev 0 Page 1 of 35 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. Page 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 2.0 INTRODUCTION 4 2.1 Name of FMU 4 2.2 Contact Person and Address 4 2.3 General Background on the Kedah FMU 4 2.4 Date First Certified 4 2.5 Location of the FMU 4 2.6 Forest Management System 5 2.7 Annual Allowable Cut/ Annual Harvest Under the Forest Management Plan 5 2.8 Environmental and Socioeconomic Context 5 3.0 AUDIT PROCESS 5 3.1 Audit Dates 5 3.2 Audit Team 5 3.3 Standard Used 5 3.4 Stakeholder Consultations 5 3.5 Audit Process 6 4.0 SUMMARY OF AUDIT FINDINGS 6 Attachments 1 Map of Kedah FMU 21 2 Experiences and Qualifications of Audit Team Members 22 3 Comments Received From Stakeholders and Responses by Audit Team Leader 25 4 Surveillance 1 Audit Plan 27 5 Details on NCRs and OFIs Raised During this Surveillance 1 Audit and 29 Corrective Actions Taken 6 Corrective Actions Taken and Final Status of NCRs and OFIs Raised During Previous 34 Audit. -

RIVER REHABILITATION of SG. MUDA, KEDAH Contents

RIVER REHABILITATION OF SG. MUDA, KEDAH Contents • Objectives • Scope of Work • Sg. Muda Recent Floods • Hydrological Modelling • River Modelling Objectives • Ensure that design cross-sections and alignment of the main river channel are economic, effective and environmentally sound; • Propose alternative designs for identified locations to meet the above requirements; • Examine the long term river behaviour through model studies, to minimise expensive repair works in future resulting from the new alignment. Scope of Work (a) Rainfall data in space and time leading to chosen flood events. (b) Runoff discharge and stage records of the chosen events; (c) Computer simulation of the flood events; (d) Computer simulation of long term river behaviour to determine stretches prone to meandering, hence needing extra protection; (e) Changes in alluvial river geometry in terms of aggradation and degradation as well as lateral channel migration as a result of the flood events; (f) Design criteria used for the Flood Control Remediation Plan; (g) Specific design of the proposed structures including levee protection, riverbank protection works and protection of bridge crossings and other structures. SITE VISITS Site Visit Site Visit Sg. Muda River Mouth Site Visit New Bridge At Sg. Muda Near Kota Kuala Muda Site Visit Construction of New Sg. Muda Barrage Site Visit New Sg. Muda Barrage Site Visit Houses Extended into River Reserve Site Visit Flood Plain (Padi Field) along Muda River Near Rantau Panjang Site Visit Phase II Flood Mitigation Project at Muda River (Pekula Pumping Station) Site Visit Abandoned Recreational Park at Pekula Pumping Station Site Visit Construction Works at Pekula Pumping Station Site Visit Irrigation Canals at Pekula Pumping Station (25th May 2005) Site Visit Sand Mining Activities Site Visit Sg. -

Kedah-Perlis Water Management Study

--- -----~------~. MIS S ION RE PORT --------------------~-------- KEDAH - PERLIS WATER· r1:~N~IGEr1ENT STUDY SURFI\CE HATER RESrJURCES· SURVEY b IJ lJIo. J. H. SIRCOULON Chief of the Technical DepaPtment . Hydrological Se~1,)ice of ORSTOM (13th November to 2nd December 1978 } -=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-:-=-=-=-=-=-"=-:-=-=- RENARVET ENGINEERING PARIS, VECEMBER 1978 C. 0 N TEN TS P age INTRODUCTION 1. - ANALYSIS and NEEDS FOR THE STUDY 1 1• 7." - RAI"NFALL •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••'. e.•••••••••• , 1 1.1.1. - Available data 1 1.1.2. - Setting up the file of reliable data ..................1 1.1.2.1. - SeZeationof rainfaZZ station ..•..•.•.•..•. 1 1.1.2.2.- Considerations on existing data and needs ..............••.•."•.•.•..••..••.• ·e. 2 1.1.2.3. - CompZetement and Homogeneity aheaking....... 4 1.1.2.4. - Use of rainfan data ~...... 5 1•2. - RUNO FF " ~ • ~.. •••• 5 . 1.2.1. - Inventory of available data ••••••••••..•••.••••••••••• ~ 5 1.2.2. - Setting up the file of reliable data.................. 6 1.2.2.1. - SeZeation of gauging stations............... 6 1. 2. 2.2. ~ Needs for the study ••••••••.. ~ •• . •• ••••••••. 6 1.2.2.3. - Use for stream flow record$ 10 1.2~2~4. - SuppZementaZ requests •.••••.•••••••.••••••• · 10 1•3. - EVAPOAATlON- •••••••"••••• ~ •••"•• "•••••••••••••••• it •••••• e· •••••••••• 10 ·1.3.1. ~ Existing.da.ta ..•••••••.• ~ •••••••••••••• ~ ••••••••••••• •••• 10 1.3.2. -. Needs for the study •••••• ••••••• ~ ••••••••••••••••••••••. 11 1.4.-VAMS ••••••••••••••••• ~ ••••.•••••••••••••••.•••••• •••••••••••• ~ 11 2. - USE OF THE SURFACE WATER RESOURCES IN THE SIMULATION MODEL • ~.. •• • •• ••• 13 2.1. - GENERAL CONSIVERATlONS •••••••••••••••• eO...... .. .. 13 2.2. - REMARKS ABOUT THE CONSTITUTION OF THE "RESOURCE SAMPLES" ••••• 13 . 3. CONCLUSIONS ............................................................ 17 4. - ANN E X· ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••,••••••••••0. .. .. 18 4.1 •. - wt 06 the Jta.in6a..te /,ta.:ti.0n6 with peJLi.od 06 JLec.oJtd6........... -

Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya Malaysia Negeri : Kedah

SURUHANJAYA PILIHAN RAYA MALAYSIA SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : KEDAH SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : KEDAH BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN : LANGKAWI BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : AYER HANGAT KOD BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : 004/01 SENARAI DAERAH MENGUNDI DAERAH MENGUNDI BILANGAN PEMILIH 004/01/01 KUALA TERIANG 1,370 004/01/02 EWA 1,416 004/01/03 PADANG LALANG 2,814 004/01/04 KILIM 1,015 004/01/05 LADANG SUNGAI RAYA 1,560 004/01/06 WANG TOK RENDONG 733 004/01/07 BENDANG BARU 1,036 004/01/08 ULU MELAKA 1,642 004/01/09 NYIOR CHABANG 1,436 004/01/10 PADANG KANDANG 1,869 004/01/11 PADANG MATSIRAT 621 004/01/12 KAMPUNG ATAS 1,205 004/01/13 BUKIT KEMBOJA 2,033 004/01/14 MAKAM MAHSURI 1,178 JUMLAH PEMILIH 19,928 SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : KEDAH BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN : LANGKAWI BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : KUAH KOD BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : 004/02 SENARAI DAERAH MENGUNDI DAERAH MENGUNDI BILANGAN PEMILIH 004/02/01 KAMPUNG GELAM 1,024 004/02/02 KEDAWANG 1,146 004/02/03 PANTAI CHENANG 1,399 004/02/04 TEMONYONG 1,078 004/02/05 KAMPUNG BAYAS 1,077 004/02/06 SUNGAI MENGHULU 2,180 004/02/07 KELIBANG 2,042 004/02/08 DUNDONG 1,770 004/02/09 PULAU DAYANG BUNTING 358 004/02/10 LUBOK CHEMPEDAK 434 004/02/11 KAMPUNG TUBA 1,013 004/02/12 KUAH 2,583 004/02/13 KAMPUNG BUKIT MALUT 1,613 JUMLAH PEMILIH 17,717 SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN -

Ground Penetrating Radar Method to Detect Archaeological Remains at Bukit Choras, Yan, Kedah: Preliminary Results

Journal of Sustainability Science and Management eISSN: 2672-7226 Volume 15 Number 7, October 2020: 102-112 © Penerbit UMT GROUND PENETRATING RADAR METHOD TO DETECT ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS AT BUKIT CHORAS, YAN, KEDAH: PRELIMINARY RESULTS NORDIANA MOHD MUZTAZA1,2, NASHA RODZIADI KHAW*3, SURESH NARAYANEN3, NURUL FITRIAH AHMAD ZAIDI1, NUR ALISHA AKRAM1, NINI HAVELA DISHONG3, NAZRIN RAHMAN1, NAJMIAH ROSLI1, NUR AZWIN ISMAIL1,2, ROSLI SAAD1, ANDY ANDERSON BERY1, SHYEH SAHIBUL KARAMAH MASNAN3 SHAIFUL IDZWAN SHAHIDAN3 AND MOHD MOKHTAR SAIDIN3 1School of Physics, 11800 Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Penang, Malaysia. 2Centre of Tropical Geoengineering, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310 UTM Johor Bahru, Johor, Malaysia. 3Centre for Global Archaeological Research Malaysia, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Pulau Pinang, Malaysia.. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Submitted final draft:23 April 2020 Accepted: 30 April 2020 http://doi.org/10.46754/jssm.2020.10.010 Abstract: Ground penetrating radar (GPR) is a geophysical method that employs broad spectrum electromagnetic waves to detect buried features without physically altering the environment. A GPR survey was performed on a 7th Century C.E. archaeological site in Bukit Choras, Kota Sarang Semut, Kedah. The site contains cultural ruins of a stupa made of laterite blocks, as well as a few mounds and scattered bricks. The geostrategic position of this site opens the possibility for the discovery of more extensive building structures. Thus, a GPR survey was conducted to test the hypothesis on the presence of more buried structures around the stupas. A total of 13 survey lines with 250 MHz shielded antenna were set up at the site, covering an area of 2040 m2. -

Determination of Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents, Antioxidant

335 AGRIVITA Journal of Agricultural Science. 2017. 39(3): 335-344 Determination of Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents, Antioxidant Activities and GC-MS Analysis of Clinacanthus nutans (Acanthaceae) in Different Locations Noor Zafirah Ismail1), Hasni Arsad1*), Mohammed Razip Samian2) and Mohammad Razak Hamdan3) 1) Advanced Medical and Dental Institute, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Bertam, 13200 Kepala Batas, Penang, Malaysia 2) School of Biological Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Gelugor, Penang, Malaysia 3) Central Drug Research Institute, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Gelugor, Penang, Malaysia *) Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 28, 2016 /Accepted: July 28, 2017 ABSTRACT things same goes Clinacanthusto nutans that have its own role in pharmaceutical remedies in South- Clinacanthus nutans is an essential medicinal plant East Asia such as Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, that had been used in various local remedies to Vietnam and China (Ismail, Arsad, Samian, Ab. treat many illnesses. A study had been conducted Majid, & Hamdan, 2016). C. nutans belongs to to determine the phenolic, flavonoid, antioxidant family Acanthaceae that can be described as herbs activities and phytochemical compounds of or perennial shrubs that can grow up to 1 m tall. In C. nutans in different locations. C. nutans were Malaysia, it is well-known as ‘Belalai Gajah’ because harvested from eight locations and the leaves of the curve stems appearances that resemble the were extracted with 80 % methanol by maceration curve of elephant’s trunk that means Belalai Gajah process. Then, the phytochemical screening using in Malay word. Confirming to the people who used Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), leaves of C. -

Senarai Nama Calon Yang Telah Berjaya Melepasi Syarat Asas Permohonan Jawatan Pemandu Kenderaan, Gred H11 Jabatan Perhutanan Negeri Kedah Bagi Tahun 2019

SENARAI NAMA CALON YANG TELAH BERJAYA MELEPASI SYARAT ASAS PERMOHONAN JAWATAN PEMANDU KENDERAAN, GRED H11 JABATAN PERHUTANAN NEGERI KEDAH BAGI TAHUN 2019 TARIKH UJIAN : 17 SEPTEMBER 2019 (SELASA) TEMPAT UJIAN : PUSAT LATIHAN PERHUTANAN JENIANG, SIK NOMBOR SIRI NO. KAD BIL. NAMA ALAMAT NO. TELEFON BORANG PENGENALAN NO 69, KAMPUNG PENYARUM MUKIM TOBIAR, 06700, 1 000756 MOHD ZAIFUL NAZRIL BIN ZAKARIA 870622-02-5683 016-9221517 PENDANG KEDAH P50 KAMPUNG ALOR PUDAK KOTA SARANG SEMUT 2 000716 MUHAMMAD FADHLI BIN CHE ANI 961219-02-5425 011-14463987 06800 ALOR SETAR KEDAH NO 33, KM 10, GUNONG KERIANG, 06570 ALOR SETAR, 3 000403 MOHD IZHAR BIN OSMAN 941020-02-5411 019-9933460 KEDAH 4 000112 MOHAMAD AMIRUL AIZAM BIN ANUAR 931008-08-6247 350, TAMAN SENA, LABU BESAR, KULIM,09010,KEDAH 01126451029 NO 15, JALAN BAIDURI 1, TAMAN TELUK BAIDURI, 08000 MUHAMMAD YASEEN ISKANDAR BIN 0134765227/ 5 000329 930731-07-5227 SUNGAI PETANI, KEDAH MOHAMAD YATIN 01116555227 34-B TAMAN WIRA MERGONG, 05150 ALOR SETAR, 6 000339 MUHAMMAD AMIN BIN ABU BAKAR 930812-02-5109 TIADA KEDAH F262, KAMPUNG SUNGAI PERAHU, 08200, JENIANG, 7 000720 NORNIKMAN BIN MUSTAZA 920915-06-5307 011-28948440 GURUN, KEDAH 8 000074 MOHAMAD SAFFWAN BIN OTHMAN 921005-02-6207 135 D, TAMAN SERI JERAI 2, 08300, GURUN KEDAH 0175214066 NO.290 PERSIARAN 11, BANDAR BARU BERIS JAYA 9 000528 AHMAD SYUKRI FAIZ BIN ELIAS 920902-02-5893 017-5166904 08200 SIK KEDAH NO 5, KAMPUNG HUMA, MUKIM PADANG HANG, 06250 10 000021 MOHD YUSUF BIN AHMAD ZAINON 921005-02-5159 014-9361368 ALOR SETAR, KEDAH 169, TAMAN SIREH,