E.1 DEPRESSION in CHILDREN and ADOLESCENTS 2015 Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dietary Patterns Are Differentially Associated with Atypical and Melancholic Subtypes of Depression

nutrients Article Dietary Patterns Are Differentially Associated with Atypical and Melancholic Subtypes of Depression Aurélie M. Lasserre 1,* , Marie-Pierre F. Strippoli 1 , Pedro Marques-Vidal 2 , Lana J. Williams 3, Felice N. Jacka 3, Caroline L. Vandeleur 1, Peter Vollenweider 2 and Martin Preisig 1 1 Department of Psychiatry, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] (M.-P.F.S.); [email protected] (C.L.V.); [email protected] (M.P.) 2 Department of Medicine, Internal Medicine, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] (P.M.-V.); [email protected] (P.V.) 3 Barwon Health, IMPACT—The Institute for Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Translation, Deakin University, Geelong 3220, Australia; [email protected] (L.J.W.); [email protected] (F.N.J.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-21-314-3552 Abstract: Diet has been associated with the risk of depression, whereas different subtypes of depres- sion have been linked with different cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs). In this study, our aims were to (1) identify dietary patterns with exploratory factor analysis, (2) assess cross-sectional associations between dietary patterns and depression subtypes, and (3) examine the potentially mediating effect of dietary patterns in the associations between CVRFs and depression subtypes. In the first follow-up of the population-based CoLaus|PsyCoLaus study (2009–2013, 3554 participants, 45.6% men, mean age Citation: Lasserre, A.M.; Strippoli, 57.5 years), a food frequency questionnaire assessed dietary intake and a semi-structured interview M.-P.F.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Williams, allowed to characterize major depressive disorder into current or remitted atypical, melancholic, L.J.; Jacka, F.N.; Vandeleur, C.L.; and unspecified subtypes. -

The Clinical Picture of Depression in Preschool Children

The Clinical Picture of Depression in Preschool Children JOAN L. LUBY, M.D., AMY K. HEFFELFINGER, PH.D., CHRISTINE MRAKOTSKY, PH.D., KATHY M. BROWN, B.A., MARTHA J. HESSLER, B.S., JEFFREY M. WALLIS, M.A., AND EDWARD L. SPITZNAGEL, PH.D. ABSTRACT Objective: To investigate the clinical characteristics of depression in preschool children. Method: One hundred seventy- four subjects between the ages of 3.0 and 5.6 years were ascertained from community and clinical sites for a compre- hensive assessment that included an age-appropriate psychiatric interview for parents. Modifications were made to the assessment of DSM-IV major depressive disorder (MDD) criteria so that age-appropriate manifestations of symptom states could be captured. Typical and “masked” symptoms of depression were investigated in three groups: depressed (who met all DSM-IV MDD criteria except duration criterion), those with nonaffective psychiatric disorders (who met cri- teria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and/or oppositional defiant disorder), and those who did not meet criteria for any psychiatric disorder. Results: Depressed preschool children displayed “typical” symptoms and vegetative signs of depression more frequently than other nonaffective or “masked” symptoms. Anhedonia appeared to be a specific symptom and sadness/irritability appeared to be a sensitive symptom of preschool MDD. Conclusions: Clinicians should be alert to age-appropriate manifestations of typical DSM-IV MDD symptoms and vegetative signs when assessing preschool children for depression. “Masked” symptoms of depression occur in preschool children but do not predomi- nate the clinical picture. Future studies specifically designed to investigate the specificity and sensitivity of the symp- toms of preschool depression are now warranted. -

Alteration of Immune Markers in a Group of Melancholic Depressed Patients and Their Response to Electroconvulsive Therapy

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author J Affect Manuscript Author Disord. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 February 03. Published in final edited form as: J Affect Disord. 2016 November 15; 205: 60–68. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.035. Alteration of Immune Markers in a group of Melancholic Depressed patients and their Response to Electroconvulsive Therapy Gavin Rush1,*, Aoife O’Donovan2,3,4,5, Laura Nagle1, Catherine Conway1, AnnMaria McCrohan2,3, Cliona O’Farrelly6, James V. Lucey1, and Kevin M. Malone2,3 1St. Patrick’s University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland 2School of Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland 3Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Mental Health Research, St. Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland 4Stress and Health Research Program, San Francisco Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco, California 5Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco, California 6School of Biochemistry and Immunology, University of Dublin Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland Abstract Background—Immune system dysfunction is implicated in the pathophysiology of major depression, and is hypothesized to normalize with successful treatment. We aimed to investigate immune dysfunction in melancholic depression and its response to ECT. Methods—55 melancholic depressed patients and 26 controls participated. 33 patients (60%) were referred for ECT. Blood samples were taken at baseline, one hour after the first ECT session, and 48 hours after ECT series completion. Results—At baseline, melancholic depressed patients had significantly higher levels of the pro- inflammatory cytokine IL-6, and lower levels of the regulatory cytokine TGF-β than controls. A significant surge in IL-6 levels was observed one hour after the first ECT session, but neither IL-6 nor TGF-β levels normalized after completion of ECT series. -

Anxiety and Depression in Older Adults

RESEARCH BRIEF #8 ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION IN OLDER ADULTS 150 000 elderly people suffer from depression in Swedenà Approximately half of older adults with depression in population surveys have residual problems several years later à Knowledge about de- pression and anxiety in older adults is limited, even though these conditions can lead to serious nega- tive consequences à More research is needed on prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is associated with 1. Introduction a constant anxiety and excessive fear and anxiety about various everyday activities (anticipatory anxiety). Sweden has an ageing population. Soon every fourth Panic disorder is associated with panic attacks (distinct person in Sweden will be over 65. Depression and anxiety periods of intense fear, terror or significant discomfort). disorders are common in all age groups. However, these Specific phobia is a distinct fear of certain things or conditions have received significantly less attention than situations (such as spiders, snakes, thunderstorms, high SUMMARY dementia within research in the older population (1, 2). altitudes, riding the elevator or flying). The number of older people is increasing Psychiatry research has also neglected the older popu- Social phobia is characterised by strong fear of social situ- across the world. Depression and anxiety lation. Older people with mental health problems are ations involving exposure to unfamiliar people or to being is common in this age group, as among also a neglected group in the care system, and care varies critically reviewed by others. Forte is a research council that funds and initiates considerably between different parts of the country. -

Ketamine and Depression: a Review Wesley C

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 33 | Issue 2 Article 6 7-1-2014 Ketamine and Depression: A Review Wesley C. Ryan University of Washington Cole J. Marta University of California, Los Angeles Ralph J. Koek University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychiatry and Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ryan, W. C., Marta, C. J., & Koek, R. J. (2014). Ryan, W. C., Marta, C. J., & Koek, R. J. (2014). Ketamine and depression: A review. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 33(2), 40–74.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 33 (2). http://dx.doi.org/ 10.24972/ijts.2014.33.2.40 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ketamine and Depression: A Review Wesley C. Ryan University of Washington Seattle, WA, USA Cole J. Marta Ralph J. Koek University of California at Los Angeles University of California at Los Angeles North Hills, CA, USA North Hills, CA, USA Ketamine, via intravenous infusions, has emerged as a novel therapy for treatment-resistant depression, given rapid onset and demonstrable efficacy in both unipolar and bipolar depression. Duration of benefit, on the order of days, varies between these subtypes, but appears longer in unipolar depression. -

Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Mild Depression

Research and Reviews Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Mild Depression JMAJ 54(2): 76–80, 2011 Tomifusa KUBOKI,*1 Masahiro HASHIZUME*2 Abstract The chief complaint of those suffering from mild depression is insomnia, followed by physical symptoms such as fatigability, heaviness of the head, headache, abdominal pain, stiffness in the shoulder, lower back pain, and loss of appetite, rather than depressive symptoms. Since physical symptoms are the chief complaint of mild depres- sion, there is a global tendency for the patients to visit a clinical department rather than a clinical psychiatric department. In Mild Depression (1996), the author Yomishi Kasahara uses the term “outpatient depression” for this mild depression and described it as an endogenous non-psychotic depression. The essential points in diagnosis are the presentation of sleep disorders, loss of appetite or weight loss, headache, diminished libido, fatigability, and autonomic symptoms such as constipation, palpitation, stiffness in the shoulder, and dizziness. In these cases, a physical examination and tests will not confirm any organic disease comparable to the symptoms, but will confirm daily mood fluctuations, mildly depressed state, and a loss of interest and pleasure. Mental rest, drug therapy, and support from family and specialists are important in treatment. Also, a physician should bear in mind that his/her role in the treatment differs somewhat between the early stage and chronic stage (i.e., reinstatement period). Key words Mild depression, Outpatient depression, -

A History of the Pharmacological Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review A History of the Pharmacological Treatment of Bipolar Disorder Francisco López-Muñoz 1,2,3,4,* ID , Winston W. Shen 5, Pilar D’Ocon 6, Alejandro Romero 7 ID and Cecilio Álamo 8 1 Faculty of Health Sciences, University Camilo José Cela, C/Castillo de Alarcón 49, 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain 2 Neuropsychopharmacology Unit, Hospital 12 de Octubre Research Institute (i+12), Avda. Córdoba, s/n, 28041 Madrid, Spain 3 Portucalense Institute of Neuropsychology and Cognitive and Behavioural Neurosciences (INPP), Portucalense University, R. Dr. António Bernardino de Almeida 541, 4200-072 Porto, Portugal 4 Thematic Network for Cooperative Health Research (RETICS), Addictive Disorders Network, Health Institute Carlos III, MICINN and FEDER, 28029 Madrid, Spain 5 Departments of Psychiatry, Wan Fang Medical Center and School of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, 111 Hsin Long Road Section 3, Taipei 116, Taiwan; [email protected] 6 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Valencia, Avda. Vicente Andrés, s/n, 46100 Burjassot, Valencia, Spain; [email protected] 7 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Complutense University, Avda. Puerta de Hierro, s/n, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 8 Department of Biomedical Sciences (Pharmacology Area), Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Alcalá, Crta. de Madrid-Barcelona, Km. 33,600, 28871 Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: fl[email protected] or [email protected] Received: 4 June 2018; Accepted: 13 July 2018; Published: 23 July 2018 Abstract: In this paper, the authors review the history of the pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder, from the first nonspecific sedative agents introduced in the 19th and early 20th century, such as solanaceae alkaloids, bromides and barbiturates, to John Cade’s experiments with lithium and the beginning of the so-called “Psychopharmacological Revolution” in the 1950s. -

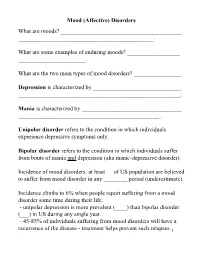

Mood (Affective) Disorders What Are Moods? ______

Mood (Affective) Disorders What are moods? _________________________________________ ______________________________________________. What are some examples of enduring moods? __________________ _______________________. What are the two main types of mood disorders? ________________ Depression is characterized by ______________________________ _______________________________________________________; Mania is characterized by __________________________________ ________________________________________________. Unipolar disorder refers to the condition in which individuals experience depressive symptoms only. Bipolar disorder refers to the condition in which individuals suffer from bouts of mania and depression (aka manic-depressive disorder). Incidence of mood disorders: at least __ of US population are believed to suffer from mood disorder in any ________ period (underestimate). Incidence climbs to 6% when people report suffering from a mood disorder some time during their life. - unipolar depression is more prevalent (____) than bipolar disorder (___) in US during any single year. - 45-85% of individuals suffering from mood disorders will have a recurrence of the disease - treatment helps prevent such relapses.1 Diagnostic criteria for Mania Criterion A - a distinct period of abnormally and persistently ______________ ____________________________. - abnormally here is defined in relation to the person’s normal behavior; - usually lasts _________________. Criterion B (requires 3 of the following symptoms, 4 if the mood is characterized as irritable): 1. __________________________________; 2. ________________________ (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep); 3. More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking; 4. ___________ (jumping to a new line of thought before completing the preceding one) or subjective experience that thoughts are racing; 5. ___________ (i.e., attention easily drawn by unimportant stimuli); 6. Increase in goal-directed activity (socially, at work or school, or sexually) or _____________________; 7. -

A Practical Approach to Subtyping Depression Among Your Patients

SECOND OF 2 PARTS A practical approach to subtyping depression among your patients Improve outcomes by understanding the forms that depressive disorders can take epression—sad, empty, or irritable mood accompanied by somatic or cognitive changes—is not a homoge- Dneous condition. Recognizing subtypes of depressive illness can guide treatment and relieve your patient’s suf- fering. In this 2-part article [April and May 2014 issues], I summarize information about clinically distinct subtypes of depression, as they are recognized within diagnostic systems or as descriptors of treatment outcomes for particular sub- groups of patients. My focus is on practical considerations for assessing and managing depression. Because many forms of the disorder respond inadequately to initial antidepressant treatment, optimal “next-step” pharmacotherapy, after nonre- sponse or partial response, often hinges on clinical subtyping. JON KRAUSE/THE ISPOT.COM The second part of this article examines “situational,” treat- ment-resistant, melancholic, agitated, anxious, and atypical Joseph F. Goldberg, MD depression; depression occurring with a substance use disor- Clinical Professor of Psychiatry Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai der; premenstrual dysphoric disorder; and seasonal affective New York, New York disorder. Treatments for these subtypes for which there is evi- Director, Affective Disorders Research Program dence, or a clinical rationale, are given in the Table, page 42. Silver Hill Hospital New Canaan, Connecticut ‘Situational’ depression In recent decades, the phenomenon of nonsyndromal depres- sion after a life stress has undergone many name changes but lit- tle conceptual revision: “situational,” “reactive,” and “neurotic” labels for depression that were used before DSM-III became “adjustment disorders” in DSM-IV-TR and then “stress Disclosure Dr. -

Phenomenal Depth a Common Phenomenological Dimension in Depression and Depersonalization

Michael Gaebler,* Jan-Peter Lamke,* Judith K. Daniels and Henrik Walter Phenomenal Depth A Common Phenomenological Dimension in Depression and Depersonalization Abstract: Describing, understanding, and explaining subjective expe- rience in depression is a great challenge for psychopathology. Attempts to uncover neurobiological mechanisms of those experi- ences are in need of theoretical concepts that are able to bridge phen- omenological descriptions and neurocognitive approaches, which allow us to measure indicators of those experiences in quantitative terms. Based on our own ongoing work with patients who suffer from depersonalization disorder (DPD) and describe their experience as flat and detached from self, body, and world, we introduce the idea of phenomenal depth as such a concept. Phenomenal depth is conceptu- alized as a dimension inherent to all experiences, describing the relat- Copyright (c) Imprint Academic 2013 edness of one’s self with one’s mental processes, body, and the world. For personal use only -- not for reproduction More precisely, it captures the experience of this relatedness and embeddedness of one’s experiences, and it is thus a meta- or second- order experience. The psychopathology of DPD patients can be understood very generally as an instance of reduced phenomenal depth. We will argue that similar experiences in depression can also be understood as a reduction in phenomenal depth. We relate those ideas to neurocognitive studies of perception, emotion regulation, and the idea of predictive coding. Finally, we will speculate about possible Correspondence: Division of Mind & Brain Research, Department of Psychiatry & Psychotherapy, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, D-10117 Berlin Email: [email protected] [*] equal contribution Journal of Consciousness Studies, 20, No. -

Healing the Stigma of Depression

Healing the Stigma of Depression A Guide for Helping Professionals A resource for helping professionals of all disciplines serving people who may be affected by depression—and by its stigma. Written by Pamela Woll, MA, CADP for the Midwest AIDS Training and Education Center and the Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center Healing the Stigma of Depression: A Guide for Helping Professionals Published by: Midwest AIDS Training and Education Center Nathan Linsk, PhD, Principal Investigator Barbara Schechtman, MPH, Executive Director Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center Larry Bennett, PhD, Principal Investigator Nathan Linsk, PhD, Co-Principal Investigator Lonnetta Albright, Director Project Leader: Barbara Schechtman, MPH Co-Leader: Lonnetta Albright Author: Pamela Woll, MA, CADP Research Assistant: Charles M. Bright, LCSW, ACSW Midwest AIDS Training and Education Center Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center Jane Addams College of Social Work University of Illinois at Chicago 1640 W. Roosevelt Road, Suite 511 (M/C 779) Chicago, Illinois 60608 November, 2007 This publication was produced by the Midwest AIDS Training and Education Center (partially supported by a grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration and through funds raised independently), and the Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center (under a cooperative agreement from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. This was produced by the Midwest AIDS Training and Education Center, funded in part by HRSA Grant # H4A HA00062. For more information on obtaining copies of this publication, please call (312) 996-1373. Developed in part under a grant funded by the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. -

The Problem of Comorbidity

Clinical Psychology Review, Vol. 14. No. 6, pp. 585-603, 1994 Pergamon Copyright 0 1994 Elsevier Science Ltd Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0272-7358/94 $6.00 + .OO 0272-7358(94)E0017-5 UNMASKING UNMASKED DEPRESSION IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS: THE PROBLEM OF COMORBIDITY Constance Han-men University of California, Los Angeles Bruce E. Compas University of Vermont ABSTRACT. The unmasking of childhood depression has stimulated considerable research, but the field has drifted unintentionally toward the rezfication of childhood depression as an entity. In turn, the reification, often embodied in theform of diagnostic categorization, may contribute to premature closure on our understanding of childhood and adolescent depression. One of the major una%rem+sized characteristics of depression is that it rarely occurs by itself in children. Comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception, and thus, much of what we think we know about the disorder may be shaped by its co-occurrence with other disorders and symptoms. Accordingly, we discuss the conceptual and measure- ment issues in depression in youngsters, identify the extent of comorbidity, and then discuss some of the implications of comorbidity. Several research issues are raised concerning exploration of the meaning of comorbidity and its possible origins. PREVAILING beliefs about childhood depression that were common until fairly recently have generally been dispelled: “if it exists at all it is rare”; “if it exists it is masked as a depression equivalent such as behavior and conduct problems, school difficulties, somatic complaints, or adolescent turmoil”; “it is transitory”; “it is a developmentally normal stage.” Dispelling the first two myths, Carlson and Cantwell (1980) demonstrated that many children referred for treatment for other problems actually met adult diagnostic criteria for depression if only the clinician looked beyond the “masking” symptoms.