ICSC Legal Spring Issue 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

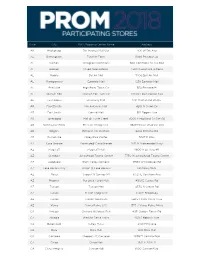

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

State City Shopping Center Address

State City Shopping Center Address AK ANCHORAGE 5TH AVENUE MALL SUR 406 W 5TH AVE AL FULTONDALE PROMENADE FULTONDALE 3363 LOWERY PKWY AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL 3400 BELL AIR MALL AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE AR JONESBORO MALL @ TURTLE CREEK 3000 E HIGHLAND DR STE 516 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MC CAIN SHOPG CNTR 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMDE 2202 BELLVIEW RD AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD AZ FLAGSTAFF FLAGSTAFF MALL 4600 N US HWY 89 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CTR 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD AZ LAKE HAVASU CITY SHOPS @ LAKE HAVASU 5651 HWY 95 N AZ MESA SUPERST'N SPRINGS ML 6525 E SOUTHERN AVE AZ NOGALES MARIPOSA WEST PLAZA 220 W MARIPOSA RD AZ PHOENIX AHWATUKEE FOOTHILLS 5050 E RAY RD AZ PHOENIX CHRISTOWN SPECTRUM 1727 W BETHANY HOME RD AZ PHOENIX PARADISE VALLEY MALL 4510 E CACTUS RD AZ TEMPE TEMPE MARKETPLACE 1900 E RIO SALADO PKWY STE 140 AZ TUCSON EL CON SHPG CNTR 3501 E BROADWAY AZ TUCSON TUCSON MALL 4530 N ORACLE RD AZ TUCSON TUCSON SPECTRUM 5265 S CALLE SANTA CRUZ AZ YUMA YUMA PALMS S C 1375 S YUMA PALMS PKWY CA ANTIOCH ORCHARD @SLATTEN RCH 4951 SLATTEN RANCH RD CA ARCADIA WESTFLD SANTA ANITA 400 S BALDWIN AVE CA BAKERSFIELD VALLEY PLAZA 2501 MING AVE CA BREA BREA MALL 400 BREA MALL CA CARLSBAD PLAZA CAMINO REAL 2555 EL CAMINO REAL CA CARSON SOUTHBAY PAV @CARSON 20700 AVALON -

Amherst • Downtown Name – Boulevard Mall Opportunity Zone • County Name - Erie • Applicant Contact(S) Name, Title, Email Address

1 D O W N T O W N R EVITALIZATION I NITIATIVE 2019 DRI Application Applications for the Downtown Revitalization Initiative (DRI) must be received by the appropriate Regional Economic Development Council (REDC) by 4:00 PM on May 31, 2019 at the email address provided at the end of this application. In New York City, the Borough Presidents’ offices will be the official applicants to the REDC and organizations interested in proposing an area for DRI funding should contact the respective Borough President’s office as soon possible. Based on these proposals, each Borough President’s office will develop and submit no more than two formal applications for consideration by the New York City REDC. Applications to the offices of the Borough President must be received by email no later than 4:00 PM on May 10, 2019. The subject heading on the email must be “Downtown Revitalization Round 4.” Applicant responses for each section should be as complete and succinct as possible. Additional information is available in the 2019 DRI Guidebook, available at www.ny.gov/DRI. Applicants in the Mid-Hudson region must limit their application to a total of 15 pages, and no attachments will be accepted. The map of the DRI Area requested in question number 1 must be part of the 15-page limit. Applicants should make every effort to engage the community in the development of the application. Prior to submission, applicants must have held a minimum of one meeting or event to solicit public input on the community vision and potential projects and should demonstrate that any input received was considered in the final application. -

The Knight Flyer Knights Join Balsa Dusters for Mall Show

THE KNIGHT FLYER April - May - June 1999 Editors: Jim Devlin - Tim Ellis KNIGHTS JOIN BALSA DUSTERS FOR MALL SHOW Once again the Boulevard Mall hosts the projects of area modelers. Scores of aircraft will be displayed at this highly successful show. The Knights have again been asked to participate. We will have about two dozen of our finest planes on display. Many of our members will also be helping to man the show. We will be promoting our upcoming rally. This show attracts a large number of people from around the WNY area. Come and see what the modelers in other clubs are doing. COMING EVENTS Mar 27 Chief’s Auction Middle School Canandaigua ,NY Apr 9/10/11 Toledo Show Convention Center Toledo, OH Apr 17 Stars Auction Olean, NY May 16 Knights Funfly Knight’s field N. Collins, NY May 22 Hall of Fame Dinner (John Grigg) Lockport, NY Jun 5/6 RCCR Fun Fly Hampton Pk Brockton Rochester, NY Jun 19/20 RC Crafters Buffalo Pattern Contest Nike site Hamburg, NY Jul 11/12 Stars Scale Rally Olean, NY Aug 7/8 Knights Scale Rally Hamburg, NY Aug 14/15 RC Crafters Pattern Contest Hamburg, NY Aug 21 NCRCMFC Combat Meet Day Rd. Lockport, NY Sept 5 RCCR 21st Annual RC Rally Phelps, NY Sept 25 8th Annual R/C Auction W. Seneca, NY FLYING KNIGHTS ON SCALE RALLY FLYERS WORLD WIDE WEB READY Those who have an Internet connection, Tom Filipiak has prepared 400 flyers have by now visited the Flying Knight's for our August scale rally. -

Visit Project Edited

Adoption STAR is a not-for-profit adoption agency in New York, Ohio and Florida. The agency firmly believes that post adoption contact (open adoption), when appropriate, is what’s best for all parties involved, especially the children. Open adoption visits between adoptive families and birth families should be a time to celebrate the adoption journey and create relationships. These visits can be as simple as a picnic in the park or going swimming at a local pool, to theme parks and adventures. Below you will find an extensive list of open adoption visit ideas for that have been suggested by Adoption STAR clients and staff members in specific areas in New York, Ohio and Florida. This list can be updated regularly, so if you have any suggestions that you do not see on the list, please email [email protected] with the subject "Open Adoption Visit Project" and we will work to add your idea. Buffalo Outdoor Activities - Erie Canal Cruise – Lockport o Sightseeing cruise that shows off history of Erie canal o Phone: (315)717-0350 o Location: 800 Mohawk St. Herimer, NY o Website: www.eriecanalcruises.com - Maid of the Mist o Boat ride through Niagara Falls o Phone: (716)248-8897 o Location: (US shipping address)151 Buffalo Avenue. Niagara Falls, NY 14303 o Website: www.maidofthemist.com - Go down to the river in Tonawanda for ice cream (Old Man River) - Participate in the Ronald McDonald House 5k run and Fisher Price Place Space o There is a 1k walk for children usually and the play space is set up next door at Canisius and always looks like lots of fun (MM) o Race takes place Wednesday, July 25 at 6:30 pm o Contact Maureen Wopperer for more info: (716)883-1177 - Sledding at Chestnut Ridge o Phone: (716)662-3290 o Location: 6121 Chestnut Ridge Road, Orchard Park, NY 14127 - Feed the ducks at Glen Falls/Ellicott Creek - Sweet Jenny’s o Ice cream and desert shop o Phone: 631-2424 o Location: 5732 Main St. -

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

Radio Shack Closing Locations

Radio Shack Closing Locations Address Address2 City State Zip Gadsden Mall Shop Ctr 1001 Rainbow Dr Ste 42b Gadsden AL 35901 John T Reid Pkwy Ste C 24765 John T Reid Pkwy #C Scottsboro AL 35768 1906 Glenn Blvd Sw #200 - Ft Payne AL 35968 3288 Bel Air Mall - Mobile AL 36606 2498 Government Blvd - Mobile AL 36606 Ambassador Plaza 312 Schillinger Rd Ste G Mobile AL 36608 3913 Airport Blvd - Mobile AL 36608 1097 Industrial Pkwy #A - Saraland AL 36571 2254 Bessemer Rd Ste 104 - Birmingham AL 35208 Festival Center 7001 Crestwood Blvd #116 Birmingham AL 35210 700 Quintard Mall Ste 20 - Oxford AL 36203 Legacy Marketplace Ste C 2785 Carl T Jones Dr Se Huntsville AL 35802 Jasper Mall 300 Hwy 78 E Ste 264 Jasper AL 35501 Centerpoint S C 2338 Center Point Rd Center Point AL 35215 Town Square S C 1652 Town Sq Shpg Ctr Sw Cullman AL 35055 Riverchase Galleria #292 2000 Riverchase Galleria Hoover AL 35244 Huntsville Commons 2250 Sparkman Dr Huntsville AL 35810 Leeds Village 8525 Whitfield Ave #121 Leeds AL 35094 760 Academy Dr Ste 104 - Bessemer AL 35022 2798 John Hawkins Pky 104 - Hoover AL 35244 University Mall 1701 Mcfarland Blvd #162 Tuscaloosa AL 35404 4618 Hwy 280 Ste 110 - Birmingham AL 35243 Calera Crossing 297 Supercenter Dr Calera AL 35040 Wildwood North Shop Ctr 220 State Farm Pkwy # B2 Birmingham AL 35209 Center Troy Shopping Ctr 1412 Hwy 231 South Troy AL 36081 965 Ann St - Montgomery AL 36107 3897 Eastern Blvd - Montgomery AL 36116 Premier Place 1931 Cobbs Ford Rd Prattville AL 36066 2516 Berryhill Rd - Montgomery AL 36117 2017 280 Bypass -

List of Designated Food Scraps Generators (PDF)

Updated 06/01/2021 New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Materials Management LIST OF DESIGNATED FOOD SCRAP GENERATORS Food Donation and Food Scraps Recycling Law The Environmental Conservation Law Section 27-2211(1) requires the Department to publish a list of designated food scrap generators (DFSG), businesses and institutions that generate 2 tons or more of food scraps per week, that are required to comply with the law. A detailed description of the methodology used by DEC to populate this list can be found here: https://www.dec.ny.gov/chemical/114499.html This list specifies which DFSGs need to comply with the donation requirements or both the donation and recycling requirements under the law. The list is organized into the following sectors: • Colleges and Universities • Correctional Facilities and Jails • Grocery & Specialty Food • Hospitality • Restaurants o Full Service o Limited Service • Supercenters • Other Generators o Amusement & Theme Parks o Casinos & Racetracks o Malls o Military Bases o Sporting Venues o Wholesale & Distribution 1 Updated 06/01/2021 Colleges & Universities Required to Required to Zip Donate Recycle Generator Code Generator Name Address City State Code x x DFSG ‐ 0001 Adelphi University One South Avenue Garden City NY 11530 x DFSG ‐ 0002 Alfred University One Saxon Dr Alfred NY 14802 Annandale On x x DFSG ‐ 0003 Bard College Bard College Hudson NY 12504 x DFSG ‐ 0004 Broome Community College Upper Front Street Binghamton NY 13902 x x DFSG ‐ 0005 Canisius College 2001 Main -

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918 AL ALABASTER COLONIAL PROMENADE 340 S COLONIAL DR NOW OPEN! 152 AL BESSEMER COLONIAL PROMENADE AT TANNEHILL 4835 PROMENADE PKWY NOW OPEN! 1650 AL FLORENCE REGENCY SQUARE 301 COX CREEK PKWY (RT 133) NOW OPEN! 2994 AL FULTONDALE PROMENADE FULTONDALE 3363 LOWERY PKWY NOW OPEN! 2218 AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA NOW OPEN! 219 AL MOBILE THE SHOPPES AT BEL AIR 3299 BEL AIR MALL NOW OPEN! 2840 AL MONTGOMERY EASTDALE MALL 1000 EASTDALE MALL NOW OPEN! 2956 AL PRATTVILLE HIGH POINT TOWN CENTER COBBS FORD RD & BASS PRO BLVD NOW OPEN! 2875 AL SPANISH FORT SPANISH FORT TOWN CENTER 22500 TOWN CENTER AVE NOW OPEN! 2869 AL TRUSSVILLE TUTWILER FARM 5060 PINNACLE SQ NOW OPEN! 1786 AL TUSCALOOSA UNIVERSITY MALL 1701 MACFARLAND BLVD E NOW OPEN! 2265 AR PINE BLUFF THE PINES MALL 2901 PINES MALL DR STE A NOW OPEN! 2709 AR FAYETTEVILLE NORTHWEST ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR NOW OPEN! 1961 AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE NOW OPEN! 2835 AR JONESBORO MALL AT TURTLE CREEK 3000 E HIGHLAND DR STE 516 NOW OPEN! 2914 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD NOW OPEN! 663 AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MCCAIN SHOPPING CENTER 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 NOW OPEN! 2879 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMENADE 2202 BELLVIEW RD NOW OPEN! 2936 AZ CASA GRANDE PROMENADE AT CASA GRANDE 1041 N PROMENADE PKWY NOW OPEN! 157 AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD NOW OPEN! 251 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER NOW OPEN! 2842 AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY -

'Rotch Sep 20 2002 Libraries

Declining Tenant Diversity in Retail Malls: 1970-2000 By Matthew M. Doelger B.A., Economics, 1998 Wheaton College Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 2002 Copyright 2002 Matthew M. Doelger All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author Depart'ment~pfrbaqSSties and Planning August 2, 2002 Certified by_ John Riordan Thomas G. Eastman Chairman, Center for Real Estate Thesis Supervisor Accepted by William C. Wheaton Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development 'ROTCH MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEP 20 2002 LIBRARIES DECLINING TENANT DIVERSITY IN RETAIL MALLS: 1970-2000 by MATTHEW M. DOELGER Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on August 2, 2002 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development ABSTRACT A study of tenant diversity in retail malls was carried out to determine if tenant diversity declined between 1970 and 2000. The study measured tenant diversity by examining the percent of tenants that occur more than once in a given set of sample malls where each occupant of a single mall space counts as a single tenant. The study examined three sets of malls: a five-mall set of malls located in Massachusetts, a five-mall set of nationally distributed malls owned by different/separate owners, and a five-mall set of malls owned by the largest owner of retail malls, Simon Property Group. -

Customer Appreciation Participating List

Pretzelmaker Customer Appreciation Day 2018 Participating Stores ADDRESS I ADDRESS II CITY STATE ZIP PHONE NUMBER Village Mall Auburn 1627 Opelika Road,#10 Auburn AL 36830 (334) 821‐8368 Brookwood Village 724 Brookwood Village Birmingham AL 35209 (205) 871‐1333 Regency Mall 301 Cox Creek Parkway,Space #1302 Florence AL 35630 (256) 760‐1980 Parkway Place Mall 2801 Memorial Parkway SW Huntsville AL 35801 (205) 539‐3255 The Shoppes at EastChase 7048 EastChase Parkway Montgomery AL 36117 (334) 356‐8111 Central Mall 5111 Rogers Avenue Fort Smith AR 72903 (479) 452‐2525 Flagstaff Mall 4650 Northe Highway 89 Flagstaff AZ 86004 Desert Sky Mall 7611 West Thomas Rd. Phoenix AZ 85033 (623) 873‐1540 Foothills Mall ‐ Bakery Cafe 7401 N La Cholla Blvd #155 Tucson AZ 85741 (520) 531‐8404 Tucson Mall 4500 N Oracle Rd Suite 212 Tucson AZ 85705 Park Place Mall 5870 East Broadway, #K‐9 Tuscon AZ 85711 Sunrise Mall 6138 Sunrise Mall Citrus Heights CA 95610 (916) 723‐7197 Bayshore Mall 3300 Broadway Spc #304A Eureka CA 95501 (707) 444‐9595 Solano Town Center 1350 Travis Blvd, Space FC98 Fairfield CA 94533 Folsom Premium Outlet 13000 Folsom Blvd.,Suite 210 Folsom CA 95630‐0002 (916) 351‐1448 Del Monte Mall 520 Del Monte Center, U‐526 Monterey CA 93940 (831) 646‐0243 Moreno Valley Mall 22500 Town Cir Ste 1205 Moreno Valley CA 92553 (951) 653‐2557 Antelope Valley Mall 1233 kW. Rancho Vista Blvd., #1111 Palmdale CA 93551 (661) 947‐8444 Galleria at Roseville 1151 Galleria Blvd.,#276 Roseville CA 95678 (916) 878‐5418 Fashion Square at Sherman 14006 Riverside Drive,Space #86 Sherman Oaks CA 91423‐6300 (818) 990‐7161 The Oaks Mall 378 W. -

Retailw O 7 S 0 B &

INC PULATION REA PO DU SE RING U 20 NL % 13 2 V EN 7, 5 RO 8 . L 2 C LM 4 S 7 N EN 8 Y 062,2 3 T , 5 E 6 T E 3 NR , G 2 N O 6 A % EW N L I R COM S LM 2 G VE E C E 9 N A A RS N N I L RE T A .6 FR 3 V 3 I N 3 O , M E 3 L IO NR 9 U T OL F A LM 5 N E O S E ALIFO N L C R T R N M T A I U 4 U A S Q . 7 T E A O . o C 0 R C 0 0 9 E M 1 A P 9 FO 0 F G M IN R N O E T O T IN H 1 S S T E N O U E F C O 8 1 I C H G . R O S A 9 T R T N 7 I E 9 M V 0 E A 6 Y S R $ T S 3,086,745,000(ASSISTED BY LVGEA) S E NEW COMPANIES U N I D 26 S N I ANNUAL HOME SALES N 7 U 4 R EMPLOYMENT 5 T E E , RETAILW O 7 S 0 B & 4 A T , 5 L 7 las vegasA perspective E 895,700 , 9.5% 6 L 7 6 UNEMPLOYMENT 4 0 RATE 6 E M M IS E LU A R LUM VO P TOU VO R M A CO ITOR E L R M VIS G TE S A T M N O M V E 6 H O G M ER M SS O $ .