Appendix IV(MJB Consulting Report)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

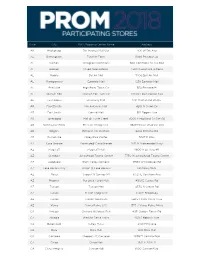

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

State City Shopping Center Address

State City Shopping Center Address AK ANCHORAGE 5TH AVENUE MALL SUR 406 W 5TH AVE AL FULTONDALE PROMENADE FULTONDALE 3363 LOWERY PKWY AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL 3400 BELL AIR MALL AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE AR JONESBORO MALL @ TURTLE CREEK 3000 E HIGHLAND DR STE 516 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MC CAIN SHOPG CNTR 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMDE 2202 BELLVIEW RD AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD AZ FLAGSTAFF FLAGSTAFF MALL 4600 N US HWY 89 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CTR 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD AZ LAKE HAVASU CITY SHOPS @ LAKE HAVASU 5651 HWY 95 N AZ MESA SUPERST'N SPRINGS ML 6525 E SOUTHERN AVE AZ NOGALES MARIPOSA WEST PLAZA 220 W MARIPOSA RD AZ PHOENIX AHWATUKEE FOOTHILLS 5050 E RAY RD AZ PHOENIX CHRISTOWN SPECTRUM 1727 W BETHANY HOME RD AZ PHOENIX PARADISE VALLEY MALL 4510 E CACTUS RD AZ TEMPE TEMPE MARKETPLACE 1900 E RIO SALADO PKWY STE 140 AZ TUCSON EL CON SHPG CNTR 3501 E BROADWAY AZ TUCSON TUCSON MALL 4530 N ORACLE RD AZ TUCSON TUCSON SPECTRUM 5265 S CALLE SANTA CRUZ AZ YUMA YUMA PALMS S C 1375 S YUMA PALMS PKWY CA ANTIOCH ORCHARD @SLATTEN RCH 4951 SLATTEN RANCH RD CA ARCADIA WESTFLD SANTA ANITA 400 S BALDWIN AVE CA BAKERSFIELD VALLEY PLAZA 2501 MING AVE CA BREA BREA MALL 400 BREA MALL CA CARLSBAD PLAZA CAMINO REAL 2555 EL CAMINO REAL CA CARSON SOUTHBAY PAV @CARSON 20700 AVALON -

Chapter 11 ) CHRISTOPHER & BANKS CORPORATION, Et Al

Case 21-10269-ABA Doc 125 Filed 01/27/21 Entered 01/27/21 15:45:17 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 22 TROUTMAN PEPPER HAMILTON SANDERS LLP Brett D. Goodman 875 Third Avenue New York, NY 1002 Telephone: (212) 704.6170 Fax: (212) 704.6288 Email:[email protected] -and- Douglas D. Herrmann Marcy J. McLaughlin Smith (admitted pro hac vice) Hercules Plaza, Suite 5100 1313 N. Market Street Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Telephone: (302) 777.6500 Fax: (866) 422.3027 Email: [email protected] [email protected] – and – RIEMER & BRAUNSTEIN LLP Steven E. Fox, Esq. (admitted pro hac vice) Times Square Tower Seven Times Square, Suite 2506 New York, NY 10036 Telephone: (212) 789.3100 Email: [email protected] Counsel for Agent UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) CHRISTOPHER & BANKS CORPORATION, et al., ) Case No. 21-10269 (ABA) ) ) (Jointly Administered) Debtors. 1 ) _______________________________________________________________________ 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases and the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, as applicable, are as follows: Christopher & Banks Corporation (5422), Christopher & Banks, Inc. (1237), and Christopher & Banks Company (2506). The Debtors’ corporate headquarters is located at 2400 Xenium Lane North, Plymouth, Minnesota 55441. Case 21-10269-ABA Doc 125 Filed 01/27/21 Entered 01/27/21 15:45:17 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 22 DECLARATION OF CINDI GIGLIO IN SUPPORT OF DEBTORS’ MOTION FOR INTERIM AND FINAL ORDERS (A)(1) CONFIRMING, ON AN INTERIM BASIS, THAT THE STORE CLOSING AGREEMENT IS OPERATIVE AND EFFECTIVE AND (2) AUTHORIZING, ON A FINAL BASIS, THE DEBTORS TO ASSUME THE STORE CLOSING AGREEMENT, (B) AUTHORIZING AND APPROVING STORE CLOSING SALES FREE AND CLEAR OF ALL LIENS, CLAIMS, AND ENCUMBRANCES, (C) APPROVING DISPUTE RESOLUTION PROCEDURES, AND (D) AUTHORIZING CUSTOMARY BONUSES TO EMPLOYEES OF STORES I, Cindi Giglio, make this declaration pursuant to 28 U.S.C. -

Clothing Retailer Charlotte Russe to Re-Open at Crossgates

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: July 9, 2019 MEDIA CONTACTS: Erin Moore Assistant Marketing Director Crossgates Management Office (518) 869-3522 [email protected] CALL IT A COMEBACK: CLOTHING RETAILER CHARLOTTE RUSSE TO RE-OPEN AT CROSSGATES -- Crossgates is one of nine locations across the Pyramid portfolio to re-open as part of the brand’s re-launch strategy to open 100 stores and a new online experience after closing down earlier this year -- ALBANY, NY – YM Inc., new owner of Charlotte Russe, is re-launching Charlotte Russe retail outlets across the U.S., with 100 planned locations set to re-open, including at Crossgates. In total, the brand will be re-opening nine locations across the Pyramid portfolio—the largest, most innovative, privately-held shopping center developer in the northeast. “We are incredibly excited to welcome back the Charlotte Russe brand to Crossgates for our guests who love the brand’s affordable, on-trend fashions,” said Erin Moore, Assistant Marketing Director at Crossgates. “A move like this speaks volumes about how dynamic, market-dominating and high-performing Crossgates is, and we know our guests share in the excitement of welcoming Charlotte Russe back.” Pyramid shopping centers and approximate openings include: ± July: Walden Galleria Holyoke Mall ± August: Poughkeepsie Galleria ± September: Crossgates ± October: Palisades Center Destiny USA ± November: Salmon Run Mall Manassas Mall ± December: Sangertown Square Charlotte Russe is a fashion brand for young women, offering affordable on-trend apparel, shoes and accessories for all sizes, with a fun and engaging shopping experience. # # # ABOUT CROSSGATES Crossgates is the Capital Region’s premier shopping, dining and entertainment destination offering an impressive selection of national brands and the newest retail concepts. -

Buffalo, NY: 716-831-7091 | Rochester, NY: 585-713-5808 Page 1

Nardin Academy 3,500 Niagara County Produce - Grind Only 31,880 1285 Main Street – Ellicott Development 19,500 Niagara Falls Amtrak Museum 525 Fairmont Creamery Apartments, Ellicott Development 35,500 Niagara Falls State Park, Gift Shop 4,125 491 Elmgrove Road, Greece NY 3,840 Niagara Falls State Park, Cave of the Winds Tunnel 1,320 Abundance Market 8,700 Niagara Falls State Park, Cave of the Winds Pavilion 1,200 Agricultural Transport 3,000 Niagara Fresh Fruit 2,250 Alleghany Farm Services, LLC. 2,100 Niagara Power Reservoir 2,950 Allegany State Park - Quaker Lakes Bathhouse 1,980 Nordstrom Rack 6,460 Amazon Warehouse offices, Lancaster NY 15,000 Polymer Conversions 3,500 Amphenol Aerospace 202,000 Praxair 12,300 B360 LLC 31,350 Praxair 2,775 Buffalo Fire Department, Bailey Ave 3,300 Premier Gourmet 5,175 Barrel Factory Distillery 5,200 Premier Wine & Spirits 20,450 BHS Food Service, retail store 3,600 ProCuts, Penfield NY 1,600 BOCES, Ellicottville Campus 2,500 Rich Products- Dolly's Café 5,000 Bradford Properties 10,000 Richardson Olmstead – Hotel Henry 3,115 Brawdy Construction 3,150 RIT – Rosica Hall 2,150 Brooke & Whittle 6,000 Roycroft Power Station, East Aurora NY 2,700 Buffalo Concrete Accessories 2,500 Samuel, Inc. 2,500 Buffalo Filter 3,600 Sefar Inc. 8,000 Buffalo Wire 1,600 Siano Building 1,100 Cabela's Retail store, Cheektowaga NY 25,100 SPCA, Erie County, West Seneca NY 14,000 CarMax – Amherst NY 2,100 SPOT Coffee, Amherst NY 1,250 CarStar, West Seneca NY 650 St. -

Amherst • Downtown Name – Boulevard Mall Opportunity Zone • County Name - Erie • Applicant Contact(S) Name, Title, Email Address

1 D O W N T O W N R EVITALIZATION I NITIATIVE 2019 DRI Application Applications for the Downtown Revitalization Initiative (DRI) must be received by the appropriate Regional Economic Development Council (REDC) by 4:00 PM on May 31, 2019 at the email address provided at the end of this application. In New York City, the Borough Presidents’ offices will be the official applicants to the REDC and organizations interested in proposing an area for DRI funding should contact the respective Borough President’s office as soon possible. Based on these proposals, each Borough President’s office will develop and submit no more than two formal applications for consideration by the New York City REDC. Applications to the offices of the Borough President must be received by email no later than 4:00 PM on May 10, 2019. The subject heading on the email must be “Downtown Revitalization Round 4.” Applicant responses for each section should be as complete and succinct as possible. Additional information is available in the 2019 DRI Guidebook, available at www.ny.gov/DRI. Applicants in the Mid-Hudson region must limit their application to a total of 15 pages, and no attachments will be accepted. The map of the DRI Area requested in question number 1 must be part of the 15-page limit. Applicants should make every effort to engage the community in the development of the application. Prior to submission, applicants must have held a minimum of one meeting or event to solicit public input on the community vision and potential projects and should demonstrate that any input received was considered in the final application. -

The Knight Flyer Knights Join Balsa Dusters for Mall Show

THE KNIGHT FLYER April - May - June 1999 Editors: Jim Devlin - Tim Ellis KNIGHTS JOIN BALSA DUSTERS FOR MALL SHOW Once again the Boulevard Mall hosts the projects of area modelers. Scores of aircraft will be displayed at this highly successful show. The Knights have again been asked to participate. We will have about two dozen of our finest planes on display. Many of our members will also be helping to man the show. We will be promoting our upcoming rally. This show attracts a large number of people from around the WNY area. Come and see what the modelers in other clubs are doing. COMING EVENTS Mar 27 Chief’s Auction Middle School Canandaigua ,NY Apr 9/10/11 Toledo Show Convention Center Toledo, OH Apr 17 Stars Auction Olean, NY May 16 Knights Funfly Knight’s field N. Collins, NY May 22 Hall of Fame Dinner (John Grigg) Lockport, NY Jun 5/6 RCCR Fun Fly Hampton Pk Brockton Rochester, NY Jun 19/20 RC Crafters Buffalo Pattern Contest Nike site Hamburg, NY Jul 11/12 Stars Scale Rally Olean, NY Aug 7/8 Knights Scale Rally Hamburg, NY Aug 14/15 RC Crafters Pattern Contest Hamburg, NY Aug 21 NCRCMFC Combat Meet Day Rd. Lockport, NY Sept 5 RCCR 21st Annual RC Rally Phelps, NY Sept 25 8th Annual R/C Auction W. Seneca, NY FLYING KNIGHTS ON SCALE RALLY FLYERS WORLD WIDE WEB READY Those who have an Internet connection, Tom Filipiak has prepared 400 flyers have by now visited the Flying Knight's for our August scale rally. -

Visit Project Edited

Adoption STAR is a not-for-profit adoption agency in New York, Ohio and Florida. The agency firmly believes that post adoption contact (open adoption), when appropriate, is what’s best for all parties involved, especially the children. Open adoption visits between adoptive families and birth families should be a time to celebrate the adoption journey and create relationships. These visits can be as simple as a picnic in the park or going swimming at a local pool, to theme parks and adventures. Below you will find an extensive list of open adoption visit ideas for that have been suggested by Adoption STAR clients and staff members in specific areas in New York, Ohio and Florida. This list can be updated regularly, so if you have any suggestions that you do not see on the list, please email [email protected] with the subject "Open Adoption Visit Project" and we will work to add your idea. Buffalo Outdoor Activities - Erie Canal Cruise – Lockport o Sightseeing cruise that shows off history of Erie canal o Phone: (315)717-0350 o Location: 800 Mohawk St. Herimer, NY o Website: www.eriecanalcruises.com - Maid of the Mist o Boat ride through Niagara Falls o Phone: (716)248-8897 o Location: (US shipping address)151 Buffalo Avenue. Niagara Falls, NY 14303 o Website: www.maidofthemist.com - Go down to the river in Tonawanda for ice cream (Old Man River) - Participate in the Ronald McDonald House 5k run and Fisher Price Place Space o There is a 1k walk for children usually and the play space is set up next door at Canisius and always looks like lots of fun (MM) o Race takes place Wednesday, July 25 at 6:30 pm o Contact Maureen Wopperer for more info: (716)883-1177 - Sledding at Chestnut Ridge o Phone: (716)662-3290 o Location: 6121 Chestnut Ridge Road, Orchard Park, NY 14127 - Feed the ducks at Glen Falls/Ellicott Creek - Sweet Jenny’s o Ice cream and desert shop o Phone: 631-2424 o Location: 5732 Main St. -

50 Thruway Plaza Drive Cheektowaga (Buffalo), NY 14225 2 2 SANDS INVESTMENT GROUP EXCLUSIVELY MARKETED BY

1 IHOP 50 Thruway Plaza Drive Cheektowaga (Buffalo), NY 14225 2 2 SANDS INVESTMENT GROUP EXCLUSIVELY MARKETED BY: ADAM SCHERR Lic. # 01925644 310.853.1266 | DIRECT [email protected] 11900 Olympic Blvd, Suite 490 Los Angeles, CA 90064 844.4.SIG.NNN www.SIGnnn.com In Cooperation With SIG RE Services NY LLC Lic. # 10991233211 BoR: Andrew AcKerman - Lic. # 10491210161 3 SANDS INVESTMENT GROUP 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 06 07 13 15 INVESTMENT OVERVIEW LEASE ABSTRACT PROPERTY OVERVIEW AREA OVERVIEW TENANT OVERVIEW Investment Summary Lease Summary Property Images City Overview Tenant Profile Investment Highlights Rent Roll Location, Aerials & Retail Maps Demographics © 2021 Sands Investment Group (SIG). The information contained in this ‘Offering Memorandum’, has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. Sands Investment Group does not doubt its accuracy; however, Sands Investment Group makes no guarantee, representation or warranty about the accuracy contained herein. It is the responsibility of each individual to conduct thorough due diligence on any and all information that is passed on about the property to determine its accuracy and completeness. Any and all proJections, market assumptions and cash flow analysis are used to help determine a potential overview on the property, however there is no guarantee or assurance these proJections, market assumptions and cash flow analysis are subJect to change with property and market conditions. Sands Investment Group encourages all potential interested buyers to seek advice from your tax, financial and legal advisors before making any real estate purchase and transaction. SANDS INVESTMENT GROUP 4 4 INVESTMENT SUMMARY Sands Investment Group is Pleased to Present Exclusively For Sale the 4 , 022 SF IHOP Located at 50 Thruway Plaza Drive in Cheektowaga (Buffalo), NY. -

Regal Makes Significant Multi-Center Investment to Transform Pyramid

For Immediate Release: July 22, 2019 MEDIA CONTACTS: Jen Smith, 518.391.4015, [email protected] Aiden McGuire, 315.466.6000, [email protected] Regal Makes Significant Multi-Center Investment to Transform Pyramid Theatres Into Immersive Cinema Guest Experiences -- Theatres at Pyramid’s Destiny USA, Crossgates and Walden Galleria set to receive significant renovations and upgrades beginning this summer -- Albany, NY – Regal, a leading motion picture exhibitor operating one of the largest theatre circuits in the United States, today announced a significant, multi-center investment to renovate multiple theatres across the Pyramid portfolio. The expansive renovations cover Destiny USA in Syracuse, Crossgates in Albany and Walden Galleria in Buffalo. The renovations will bring all-new seating, including a VIP section with luxury recliners at select locations, cafes with food and expanded drink offerings, groundbreaking 4DX and ScreenX technology to deliver an immersive cinema experience and enhance the movie going experience for Pyramid’s millions of visitors each year. "The entertainment industry is progressing further into the future, driven by cutting-edge technology and creativity," said Todd Boruff, Senior Vice President of Real Estate for Regal. "Like Pyramid, Regal is motivated to create the best movie going experience for our guests from the moment they walk through the door. To deliver on this promise, Regal has invested in top technology, including 4DX and ScreenX, the best cinema design and service, all to ensure that our customers enjoy the ultimate cinema experience." “Pyramid has always been innovative in incorporating entertainment for immersive guest experiences in the ongoing development of our portfolio of shopping, dining and entertainment destinations,” said Stephen Congel, chief executive officer, Pyramid. -

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

Radio Shack Closing Locations

Radio Shack Closing Locations Address Address2 City State Zip Gadsden Mall Shop Ctr 1001 Rainbow Dr Ste 42b Gadsden AL 35901 John T Reid Pkwy Ste C 24765 John T Reid Pkwy #C Scottsboro AL 35768 1906 Glenn Blvd Sw #200 - Ft Payne AL 35968 3288 Bel Air Mall - Mobile AL 36606 2498 Government Blvd - Mobile AL 36606 Ambassador Plaza 312 Schillinger Rd Ste G Mobile AL 36608 3913 Airport Blvd - Mobile AL 36608 1097 Industrial Pkwy #A - Saraland AL 36571 2254 Bessemer Rd Ste 104 - Birmingham AL 35208 Festival Center 7001 Crestwood Blvd #116 Birmingham AL 35210 700 Quintard Mall Ste 20 - Oxford AL 36203 Legacy Marketplace Ste C 2785 Carl T Jones Dr Se Huntsville AL 35802 Jasper Mall 300 Hwy 78 E Ste 264 Jasper AL 35501 Centerpoint S C 2338 Center Point Rd Center Point AL 35215 Town Square S C 1652 Town Sq Shpg Ctr Sw Cullman AL 35055 Riverchase Galleria #292 2000 Riverchase Galleria Hoover AL 35244 Huntsville Commons 2250 Sparkman Dr Huntsville AL 35810 Leeds Village 8525 Whitfield Ave #121 Leeds AL 35094 760 Academy Dr Ste 104 - Bessemer AL 35022 2798 John Hawkins Pky 104 - Hoover AL 35244 University Mall 1701 Mcfarland Blvd #162 Tuscaloosa AL 35404 4618 Hwy 280 Ste 110 - Birmingham AL 35243 Calera Crossing 297 Supercenter Dr Calera AL 35040 Wildwood North Shop Ctr 220 State Farm Pkwy # B2 Birmingham AL 35209 Center Troy Shopping Ctr 1412 Hwy 231 South Troy AL 36081 965 Ann St - Montgomery AL 36107 3897 Eastern Blvd - Montgomery AL 36116 Premier Place 1931 Cobbs Ford Rd Prattville AL 36066 2516 Berryhill Rd - Montgomery AL 36117 2017 280 Bypass