Archaeology and Economy in the Ancient World, Bd. 39; Boundaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kings on Coins: the Appearance of Numa on Augustan Coinage

Kings on Coins: The Appearance of Numa on Augustan Coinage AIMEE TURNER1 iconography, which he began to develop and experiment with in the triumviral period, and continued to utilise into his principate.6 Many In 22 BCE, an as was minted bearing the of the images he employed focus on religious image of Augustus Caesar on the obverse and iconography which promoted Augustus as a 7 Numa Pompilius on the reverse. Discussion of restorer of Roman tradition. In 22 BCE, an this coin in the context of Augustan ideology as was produced that featured the image of has been limited.2 Although one aspect of the Augustus on the obverse and Numa Pompilius, coin’s message relates to the promotion of the second king of Rome, on the reverse. the moneyer’s family, a closer analysis of its Numa was the quasi-legendary second king 8 iconographical and historical context provides of Rome, following Romulus. He is credited important evidence for the early public image with establishing the major religious practices 9 of Augustus, particularly in regard to religion. of the city as well as its first peaceful period. To that end, this paper intends to establish the As one of the earliest coins of the principate, traditional use of kings in Republican coins it offers important evidence for the early and the development of religious iconography public image of Augustus and the direction he in early Augustan coinage. By ascertaining intended to take at that time. His propaganda this framework, the full significance of the as was fluid, changing to meet the demands of the of 22 BCE becomes clearer. -

Reconstructing the Ancient Urban Landscape in a Long-Lived City: the Asculum Project – Combining Research, Territorial Planning and Preventative Archaeology

Archeologia e Calcolatori 28.2, 2017, 301-309 RECONSTRUCTING THE ANCIENT URBAN LANDSCAPE IN A LONG-LIVED CITY: THE ASCULUM PROJECT – COMBINING RESEARCH, TERRITORIAL PLANNING AND PREVENTATIVE ARCHAEOLOGY 1. The Asculum Project. Aims, methods and landscape In recent years the University of Bologna has gained valuable experience in the field of archaeological impact assessment and development-led archae- ology. This has been achieved within studies focused on the phenomenon of cities and urban life in antiquity, this being one of the long-standing lines of research pursued by the University’s Department of History and Cultures (Boschi 2016a). Within this general line of investigation the Asculum Project was initiated as an agreed cooperation between the University, the former Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici delle Marche and the Municipality of Ascoli Piceno, primarily as a project of urban and preventative archaeology in a long-lived city. Through that cooperation the Asculum Project aims to generate new knowledge and understanding about the past of this important city while at the same time playing an active role in the planning process within a func- tioning urban landscape, producing benefits for a wide range of interests and helping to reconcile the needs of preservation and research within the ambit of sustainable urban development. The city of Ascoli Piceno is situated in the heart of the ancient region of Picenum within the valley of the River Tronto that provides a natural com- munication route by way of the Gole del Velino to the Tiber and thence to the Tyrrhenian side of the Italian peninsula. The city originated as the main settlement of the Piceni culture, during the Iron Age, at the confluence of the River Tronto and its smaller tributary the River Castellano. -

Hispellum: a Case Study of the Augustan Agenda*

Acta Ant. Hung. 55, 2015, 111–118 DOI: 10.1556/068.2015.55.1–4.7 TIZIANA CARBONI HISPELLUM: A CASE STUDY * OF THE AUGUSTAN AGENDA Summary: A survey of archaeological, epigraphic, and literary sources demonstrates that Hispellum is an adequate case study to examine the different stages through which Augustus’ Romanization program was implemented. Its specificity mainly resides in the role played by the shrine close to the river Clitumnus as a symbol of the meeting between the Umbrian identity and the Roman culture. Key words: Umbrians, Romanization, Augustan colonization, sanctuary, Clitumnus The Aeneid shows multiple instances of the legitimization, as well as the exaltation, of the Augustan agenda. Scholars pointed out that Vergil’s poetry is a product and at the same time the producer of the Augustan ideology.1 In the “Golden Age” (aurea sae- cula) of the principate, the Romans became “masters of the whole world” (rerum do- mini), and governed with their power (imperium) the conquered people.2 In his famous verses of the so-called prophecy of Jupiter, Vergil explained the process through which Augustus was building the Roman Empire: by waging war (bellum gerere), and by gov- erning the conquered territories. While ruling over the newly acquired lands, Augustus would normally start a building program, and would substitute the laws and the cus- toms of the defeated people with those of the Romans (mores et moenia ponere).3 These were the two phases of the process named as “Romanization” by histo- rians, a process whose originally believed function has recently been challenged.4 * I would like to sincerely thank Prof. -

Modello Dichiarazione Cambio IBAN

Ambito Territoriale Sociale 19 Piazz.le Azzolino 18 – Fermo OGGETTO: Coordinate bancarie per riscossione contributo DA ALLEGARE ALLA DOMANDA Il Sottoscritto __________________________________________ nato a_____________________________prov. ______ il ____________________ cod. fisc._______________________________________________ residente a ____________________________________ in via_______________________________________prov._______ In qualita! di genitore/tutore richiedente il contributo, per il minore/amministrato_____________________________________________cod. fisc.___________________________ Nel caso in cui la domanda volta ad ottenere il contributo Regionale per “INTERVENTI EDUCATIVI/RIABILITATIVI PER PERSONE AFFETTE DA DISTURBI DELLO SPETTRO AUTISTICO” dovesse avere esito positivo, si indicano di seguito le coordinate bancarie per la riscossione del contributo: : Cognome e nome intestatario___________________________________________________________________ nato a ______________________________ il ______________prov___ cod.fisc____________________________________ residente a _______________________________________ in via _____________________________________ prov ____ Istituto Bancario___________________________________________ Sede/ Filiale______________________________ CODICE IBAN - Allego copia di un documento d’identita! in corso di validita! del richiedente e del beneficiario - Allego documento bancario contenente le coordinate bancarie del nuovo conto corrente Ente Capofila Comune di Fermo. Comuni di Altidona, Belmonte Piceno, -

Official Journal C 474 of the European Union

Official Journal C 474 of the European Union Volume 59 English edition Information and Notices 17 December 2016 Contents II Information INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2016/C 474/01 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.8300 — Hewlett Packard Enterprise Services/ Computer Sciences Corporation) (1) ......................................................................................... 1 2016/C 474/02 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.8247 — Aurelius Equity Opportunities/Office Depot (Netherlands)) (1) ......................................................................................................... 1 2016/C 474/03 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.8265 — Carlyle/KAP) (1) ................................. 2 2016/C 474/04 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.8096 — International Paper Company/ Weyerhaeuser Target Business) (1) ............................................................................................. 2 IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2016/C 474/05 Euro exchange rates .............................................................................................................. 3 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES 2016/C 474/06 Reorganisation measures — Decision on measures to reorganise ‘International Life, Life Insurance AS’ (Publication made in accordance with Article 271 of Directive 2009/138/EC -

Avviso Pubblico Erogazione Assegno Di Cura Per Anziani Non Autosufficienti

AMBITO TERRITORIALE SOCIALE XIX Ente Capofila Comune di Fermo - Comuni di Altidona, Belmonte Piceno, Campofilone, Falerone, Francavilla d'Ete, Grottazzolina, Lapedona, Magliano di Tenna, Massa Fermana, Monsampietro Morico, Montappone, Monte Giberto, Montegiorgio, Montegranaro, Monteleone di Fermo, Monte Rinaldo, Monterubbiano, Monte San Pietrangeli, Monte Vidon Combatte, Monte Vidon Corrado, Montottone, Moresco, Ortezzano, Pedaso, Petritoli, Ponzano di Fermo, Porto San Giorgio, Rapagnano, Servigliano, Torre San Patrizio. AVVISO PUBBLICO EROGAZIONE ASSEGNO DI CURA PER ANZIANI NON AUTOSUFFICIENTI RICHIAMATI: • la DGR n.1062 del 28.07.2020 “Criteri di riparto e modalità di utilizzo del Fondo Regionale per le non autosufficienze – Interventi a favore degli anziani e delle disabilità gravissime – annualità 2020” • la DGR n.1284 del 05.08.2020 “Integrazione alla DGR n.1062 del 28.07.2020: Criteri di riparto e modalità di utilizzo del Fondo Regionale per le non autosufficienze – Interventi a favore degli anziani e delle disabilità gravissime – annualità 2020” • la Deliberazione del Comitato dei Sindaci dell’Ambito Sociale XIX n. 6 del 31/08/2020; • la Determinazione Dirigenziale del Comune di Fermo n. 417 R.G.1722 del 02.10.2020, che dispone che l’erogazione di n. 110 Assegni di Cura è da intendersi puramente eventuale, in quanto condizionata all’effettivo riparto ed assegnazione del corrispondente Fondo Non Autosufficienza nazionale e regionale annualità 2020 da parte della Regione Marche agli Ambiti Territoriali Sociali, come previsto dalle rispettive DGR n. 1062/2020 e n.1284/2020 ; SI RENDE NOTO Che verrà redatta una graduatoria per l’eventuale erogazione dell’ASSEGNO DI CURA a favore di soggetti ANZIANI NON AUTOSUFFICIENTI, di importo pari ad € 200,00 mensili, per la durata di 13 mesi 01.12.2020 - 31.12.2021 . -

Erogazione Assegno Di Cura Per Anziani Non Autosufficienti

Comune di Servigliano (FM) - Protocollo in arrivo N.0000406 del 23-01-2020 - cat.7 AMBITO TERRITORIALE SOCIALE XIX Ente Capofila Comune di Fermo - Comuni di Altidona, Belmonte Piceno, Campofilone, Falerone, Francavilla d'Ete, Grottazzolina, Lapedona, Magliano di Tenna, Massa Fermana, Monsampietro Morico, Montappone, Monte Giberto, Montegiorgio, Montegranaro, Monteleone di Fermo, Monte Rinaldo, Monterubbiano, Monte San Pietrangeli, Monte Vidon Combatte, Monte Vidon Corrado, Montottone, Moresco, Ortezzano, Pedaso, Petritoli, Ponzano di Fermo, Porto San Giorgio, Rapagnano, Servigliano, Torre San Patrizio. AVVISO PUBBLICO EROGAZIONE ASSEGNO DI CURA PER ANZIANI NON AUTOSUFFICIENTI - Vista la Deliberazione di Giunta Regionale n. 1138 DEL 30/09/2019; - Vista la Deliberazione del Comitato dei Sindaci dell’Ambito Sociale XIX n. 29 del 12/12/2019; - Vista la Determinazione Dirigenziale del Comune di Fermo n.12 R.G. 44 del 14.01.2020 SI RENDE NOTO Che verrà redatta una graduatoria per l’erogazione dell’ASSEGNO DI CURA a favore di soggetti ANZIANI NON AUTOSUFFICIENTI, di importo pari ad € 200,00 mensili, per la durata di un anno (12 mesi). Sono destinatari dell’assegno di cura gli anziani ultrasessantacinquenni non autosufficienti residenti (e domiciliati) nei Comuni dell’Ambito Territoriale Sociale (ATS) n.XIX (Comuni di: Altidona, Belmonte Piceno, Campofilone, Falerone, Fermo, Francavilla d'Ete, Grottazzolina, Lapedona, Magliano di Tenna, Massa Fermana, Monsampietro Morico, Montappone, Monte Giberto, Montegiorgio, Montegranaro, Monteleone di Fermo, Monte Rinaldo, Monterubbiano, Monte San Pietrangeli, Monte Vidon Combatte, Monte Vidon Corrado, Montottone, Moresco, Ortezzano, Pedaso, Petritoli, Ponzano di Fermo, Porto San Giorgio, Rapagnano, Servigliano, Torre San Patrizio), le cui famiglie attivano interventi di supporto assistenziale gestiti direttamente dai familiari o attraverso assistenti familiari in possesso di regolare contratto di lavoro, volti a mantenere la persona anziana non autosufficiente nel proprio contesto di vita e di relazioni. -

The Roman Army's Emergence from Its Italian Origins

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Carolina Digital Repository THE ROMAN ARMY’S EMERGENCE FROM ITS ITALIAN ORIGINS Patrick Alan Kent A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Richard Talbert Nathan Rosenstein Daniel Gargola Fred Naiden Wayne Lee ABSTRACT PATRICK ALAN KENT: The Roman Army’s Emergence from its Italian Origins (Under the direction of Prof. Richard Talbert) Roman armies in the 4 th century and earlier resembled other Italian armies of the day. By using what limited sources are available concerning early Italian warfare, it is possible to reinterpret the history of the Republic through the changing relationship of the Romans and their Italian allies. An important aspect of early Italian warfare was military cooperation, facilitated by overlapping bonds of formal and informal relationships between communities and individuals. However, there was little in the way of organized allied contingents. Over the 3 rd century and culminating in the Second Punic War, the Romans organized their Italian allies into large conglomerate units that were placed under Roman officers. At the same time, the Romans generally took more direct control of the military resources of their allies as idea of military obligation developed. The integration and subordination of the Italians under increasing Roman domination fundamentally altered their relationships. In the 2 nd century the result was a growing feeling of discontent among the Italians with their position. -

Avviso Pubblicazione Graduatoria Provvisoria

AMBITO TERRITORIALE SOCIALE XIX Ente Capofila Comune di Fermo - Comuni di Altidona, Belmonte Piceno, Campofilone, Falerone, Francavilla d'Ete, Grottazzolina, Lapedona, Magliano di Tenna, Massa Fermana, Monsampietro Morico, Montappone, Monte Giberto, Montegiorgio, Montegranaro, Monteleone di Fermo, Monte Rinaldo, Monterubbiano, Monte San Pietrangeli, Monte Vidon Combatte, Monte Vidon Corrado, Montottone, Moresco, Ortezzano, Pedaso, Petritoli, Ponzano di Fermo, Porto San Giorgio, Rapagnano, Servigliano, Torre San Patrizio . AVVISO Si comunica che con determinazione dirigenziale n. 268 del 14/05/2018 R.G. 846 è stata pubblicata la graduatoria provvisoria dei soggetti richiedenti l’accesso al contributo economico dell’Assegno di Cura di cui all’Avviso Pubblico del 18/01/2018. Gli Assegni di Cura verranno erogati fino ad esaurimento dei fondi messi a disposizione dalla Regione ai sensi della D.G.R. 328/2015, e della D.G.R. 1499/2017; In relazione alle risorse del FNA 2017, sono finanziabili n. 110 assegni di cura. Si rammenta che la posizione utile nel presente elenco – stilata in base al valore ISEE - non dà di per sé diritto al contributo che sarà subordinato all’esito della valutazione professionale dell’Assistente Sociale dell’Ambito XIX e alla conclusione di un apposito patto di assistenza domiciliare Informazioni e chiarimenti potranno essere forniti presso l'Ufficio di Coordinamento dell'Ambito Sociale XIX al n. tel. 0734/603167 . ELENCO AMMESSI Cognome Stato Prog. e nome Comune residenza ISEE Note domanda AMMESSA 1 LF ALTIDONA 0,00 FINANZIATA AMMESSA 2 GA PORTO SAN GIORGIO 0,00 FINANZIATA AMMESSA 3 MM MONTERUBBIANO 580.80 FINANZIATA AMMESSA 4 PM PORTO SAN GIORGIO 586.67 FINANZIATA AMMESSA 5 LA FERMO 1.373,33 FINANZIATA AMMESSA 6 NV PORTO SAN GIORGIO 1830.67 FINANZIATA AMMESSA 7 FL FERMO 2.551,06 FINANZIATA AMMESSA 8 MC PORTO SAN GIORGIO 2821.63 FINANZIATA ______________________________________________________________ Ufficio di Coordinamento della Rete dei Servizi Sociali dell’Ambito Territoriale XIX c/o Comune di Fermo – Via Mazzini, 4 – 63023 FERMO Tel. -

Ancient Rome a History Second Edition

Ancient Rome A History Second Edition Ancient Rome A History Second Edition D. Brendan Nagle University of Southern California 2013 Sloan Publishing Cornwall-on-Hudson, NY 12520 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nagle, D. Brendan, 1936- Ancient Rome : a history / D. Brendan Nagle, University of Southern California. -- Second edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59738-042-3 -- ISBN 1-59738-042-3 1. Rome--History. I. Title. DG209.N253 2013 937--dc23 2012048713 Cover photo: Cover design by Amy Rosen, K&M Design Sloan Publishing, LLC 220 Maple Road Cornwall-on-Hudson, NY 12520 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN 13: 978-1-59738-042-3 ISBN 10: 1-59738-042-3 Brief Contents Introduction: Rome in Context 1 Part One: The Rise of Rome 13 1 The Founding of the City 21 2 Early Rome: External Challenges 37 3 The Rise of Rome: How Did it Happen? 63 4 Roman Religion 86 5 Roman Society 107 Part II: Rome Becomes an Imperial Power 125 6 The Wars with Carthage 129 7 After Hannibal: Roman Expansion 145 Part III: The Fall of the Roman Republic 159 8 The Consequences of Empire 163 9 The Crisis of the Roman Republic: The Gracchi 187 10 After the Gracchi 198 11 The Fall of the Republic: From Sulla to Octavian 210 Part IV: The Republic Restored: The Principate of Augustus 239 12 The Augustan Settlement 247 Part V: Making Permanent the Augustan Settlement 269 13 The Julio-Claudians: Tiberius to Nero 273 14 From the Flavians to the Death of Commodus 289 Part VI: The Roman Empire: What Held it Together? 305 15 What Held the Empire Together: Institutional Factors 309 16 What Held the Empire Together: Social and Cultural Factors 337 Part VII: Rome on the Defense: The Third Century A.D. -

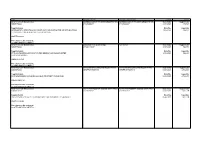

Lotto Operatori Invitati Operatori Aggiudicatari

Lotto Operatori invitati Operatori aggiudicatari Tempi Importo Area Tecnica E Manutentiva AGENZIA LANCIOTTI ASSICURAZIONI SRL AGENZIA LANCIOTTI ASSICURAZIONI SRL Data inizio Aggiudicato 80000970444 01825440447 01825440447 23/06/2021 354,50€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato AFFIDAMENTO SERVIZIO ASSICURAZIONE CUMULATIVA PER INFORTUNI VERSO 23/06/2021 354,50€ TERZI IN RIFERIMENTO ALL'ATTIVITÀ SPORTIVA. CIGZ7F3238933 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Area Tecnica E Manutentiva UnipolSai Assicurazioni Spa Non definiti Data inizio Aggiudicato 80000970444 037408112017 21/06/2021 502,65€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato STIPULA POLIZZA ASSICURATIVA PER MEZZO COMUNALE PORTER 21/06/2021 502,65€ TARGATOGA202MD CIGZ493231C85 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Area Tecnica E Manutentiva OFFICINA MECCANICA MERCURI PIERO OFFICINA MECCANICA MERCURI PIERO Data inizio Aggiudicato 80000970444 MRCPRI53T06I981X MRCPRI53T06I981X 03/03/2021 4.782,67€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato RIAPAZIONI MECCANICHE SCUOLABUS PROPRIETÀ COMUNALE 03/03/2021 4.782,67€ CIGZ2F30DCF02 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Area Tecnica E Manutentiva AUTOCARROZZERIA SILENZI GIANCARLO AUTOCARROZZERIA SILENZI GIANCARLO Data inizio Aggiudicato 80000970444 01529620443 01529620443 05/06/2021 1.037,72€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato RIPARAZIONI CARROZZERIA MITSUBISHI L200 DI PROPRIETÀ COMUNALE 05/06/2021 1.037,72€ CIGZE032008B9 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Lotto Operatori invitati Operatori aggiudicatari Tempi Importo Area Tecnica E Manutentiva DITTA TR GOMME DI TESTA SETTIMIO& C. DITTA TR GOMME DI TESTA SETTIMIO& C. Data inizio Aggiudicato 80000970444 SNC SNC 05/06/2021 410,00€ 01192550448 01192550448 Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato SOSTITUZIONE GOMME MITSUBISHI L200 DI PROPRIETÀ COMUNALE E 05/06/2021 410,00€ CONVERGENZA RUOTE ANTERIORI CIGZ303200859 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Area Tecnica E Manutentiva ENI FUEL S.P.A. -

Polycentrism and Sustainable Development in the Marche Region

Polycentrism and sustainable development in the Marche Region Project cofinanced by European Union authors Silvia Catalino - Marche Region Lorenzo Federiconi - Marche Region Matteo Moroni - Marche Region Daniele Sabbatini - Marche Region Alessandro Zepponi - Marche Region in collaboration with Antonio Minetti - Marche Region Department of Economics of Università Politecnica delle Marche SVIM Sviluppo Marche spa Roberto Capancioni - Geoservice srl This publication is printed on 100% recycled post-consumer pa- per. The paper production is environment friendly, specially for air and water emissions, consumption of energy and dangerous chemicals. The paper is certified Ecolabel , the european label of envi- ronmental auditing for products and services. index chapter 1 5 The INTERREG project “Polydev” chapter 2 17 Spatial development and polycentrism chapter 3 27 Territorial organization and paths of economic development in Marche Region A case study chapter 4 91 Conclusions bibliography 94 project partners 96 CHAPTER 1 The INTERREG project “Polydev” 1.1 Presentation of the project “Polydev” The main goal of the project “Polydev” (Common best practices in spatial planning for the promotion of sustainable polycentric deve- lopment), on a transnational scale, is the promotion of spatial and territorial planning themes in order to outline a common and integra- ted strategy for polycentric development within the member states of the CADSES areas according to the regulations outlined in the ESDP (European Spatial Development Perspective). The project involves the study of existing territorial relations between the rural/natural areas and the urban settlements. The project is also linked to the ESDP priority as regards the strengthening of decision makers’ abilities to administrate the main territorial issues and it is based on the cooperation among the various local and regional go- vernments and the comparison of the various territorial situations of the countries involved.