Connecticut Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Program Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Island Sound Habitat Restoration Initiative

LONG ISLAND SOUND HABITAT RESTORATION INITIATIVE Technical Support for Coastal Habitat Restoration FEBRUARY 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................i GUIDING PRINCIPLES.................................................................................. ii PROJECT BOUNDARY.................................................................................. iv SITE IDENTIFICATION AND RANKING........................................................... iv LITERATURE CITED ..................................................................................... vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................... vi APPENDIX I-A: RANKING CRITERIA .....................................................................I-A-1 SECTION 1: TIDAL WETLANDS ................................................1-1 DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................. 1-1 Salt Marshes ....................................................................................................1-1 Brackish Marshes .............................................................................................1-3 Tidal Fresh Marshes .........................................................................................1-4 VALUES AND FUNCTIONS ........................................................................... 1-4 STATUS AND TRENDS ................................................................................ -

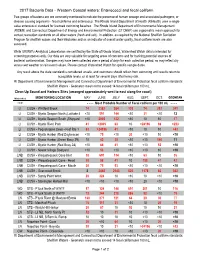

2017 Bacteria Data

2017 Bacteria Data - Western Coastal waters: Enterococci and fecal coliform Two groups of bacteria are are commonly monitored to indicate the presense of human sewage and associated pathogens, or disease causing organisms - fecal coliforms and enterococci. The Rhode Island Department of Health (RIHealth) uses a single- value enterococci standard for licensed swimming beaches. The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (RIDEM) and Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP) use a geometric mean approach for contact recreation standards on all other waters (fresh and salt). In addition, as required by the National Shellfish Sanitation Program for shellfish waters and their tributaries and as an indicator of overall water quality, fecal coliform levels are also assessed. While URIWW's Analytical Laboratories are certified by the State of Rhode Island, Watershed Watch data is intended for screening purposes only. Our data are very valuable for targeting areas of concerns and for tracking potential sources of bacterial contamination. Samples may have been collected over a period of days for each collection period, so may reflect dry versus wet weather or rain event values. Please contact Watershed Watch for specific sample dates. Any result above the state standard is considered unsafe, and swimmers should refrain from swimming until results return to acceptable levels, or at least for several days after heavy rain. RI Department of Environmental Management and Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection fecal coliform standards: Shellfish Waters - Geometric mean not to exceed 14 fecal coliform per 100 mL. Clean Up Sound and Harbors Sites (arranged approximately west to east along the coast) Watershed MONITORING LOCATION MAY JUNE JULY AUG. -

Impaired Waters Monitoring Requirements Table General Permit for the Discharge of Stormwater Associated with Industrial Activity, Effective October 1, 2011

Impaired Waters Monitoring Requirements Table General Permit for the Discharge of Stormwater Associated with Industrial Activity, effective October 1, 2011 Approved Impaired Waters Waterbody ID Waterbody Name Impaired Designated Use Pollutant Frequency TMDL? Monitoring All Waterbodies All Waterbodies Fish consumption Mercury Yes complete check box for Mercury on see 'Note 1' below registration All Waterbodies All Waterbodies Aquatic Life Use Total Nitrogen Yes TKN & NO3 monitor for these parameters as already specified in the General Permit unless notified by CTDEP CT1000-00_01 Pawcatuck River-01 Recreation Bacteria No see 'Note 2' below Annually CT1001-00-1-L1_01 Wyassup Lake (North Recreation Non-Native Aquatic No None n/a Stonington) Plants CT1001-00-1-L1_01 Wyassup Lake (North Fish Consumption Mercury Yes complete check box for Mercury on see 'Note 1' below Stonington) registration CT2000-30_01 Fenger Brook-01 Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life Cause Unknown No None n/a and Wildlife CT2000-30_01 Fenger Brook-01 Recreation Bacteria No see 'Note 2' below Annually CT2102-00_01 Copps Brook-01 Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life Cause Unknown No None n/a and Wildlife CT2102-00_01 Copps Brook-01 Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life Other flow regime No None n/a and Wildlife alterations CT2102-00-trib_01 Unnamed Trib to Copps Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life Other flow regime No None n/a Brook-01 and Wildlife alterations CT2104-00_02a Whitford Brook-02a Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life Other flow regime No None n/a and Wildlife -

Connecticut's Second Generation Nitrogen Strategy

Table of Contents Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Second Generation Nitrogen Strategy ............................................................................................ 4 Wastewater Treatment Plants ..................................................................................................... 4 Nonpoint Sources and Stormwater ............................................................................................. 4 Embayments ................................................................................................................................ 5 Status of Nitrogen Loading to Long Island Sound ......................................................................... 8 Hypoxia Trends in Offshore Long Island Sound .......................................................................... 10 Nitrogen Loading and Embayments ............................................................................................. 12 EPA’s Nitrogen Reduction Strategy ............................................................................................. 15 Relevant Reports and Publications ............................................................................................... 16 On the Cover: Long Island Sound Aerial Photo Source – UCONN https://lis.research.cuconn.edu/ -

Connecticut Aquatic Nuisance Species Management Plan

CONNECTICUT AQUATIC NUISANCE SPECIES MANAGEMENT PLAN Connecticut Aquatic Nuisance Species Working Group TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 3 Acknowledgements 5 Executive Summary 6 1. INTRODUCTION 10 1.1. Scope of the ANS Problem in Connecticut 10 1.2. Relationship with other ANS Plans 10 1.3. The Development of the CT ANS Plan (Process and Participants) 11 1.3.1. The CT ANS Sub-Committees 11 1.3.2. Scientific Review Process 12 1.3.3. Public Review Process 12 1.3.4. Agency Review Process 12 2. PROBLEM DEFINITION AND RANKING 13 2.1. History and Biogeography of ANS in CT 13 2.2. Current and Potential Impacts of ANS in CT 15 2.2.1. Economic Impacts 16 2.2.2. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Impacts 19 2.3. Priority Aquatic Nuisance Species 19 2.3.1. Established ANS Priority Species or Species Groups 21 2.3.2. Potentially Threatening ANS Priority Species or Species Groups 23 2.4. Priority Vectors 23 2.5. Priorities for Action 23 3. EXISTING AUTHORITIES AND PROGRAMS 30 3.1. International Authorities and Programs 30 3.2. Federal Authorities and Programs 31 3.3. Regional Authorities and Programs 37 3.4. State Authorities and Programs 39 3.5. Local Authorities and Programs 45 4. GOALS 47 3 5. OBJECTIVES, STRATEGIES, AND ACTIONS 48 6. IMPLEMENTATION TABLE 72 7. PROGRAM MONITORING AND EVALUATION 80 Glossary* 81 Appendix A. Listings of Known Non-Native ANS and Potential ANS in Connecticut 83 Appendix B. Descriptions of Species Identified as ANS or Potential ANS 93 Appendix C. -

Contract 17-04 Anguilla Brook Bacteria Trackdown and Watershed-Based Plan Eastern Connecticut Conservation District January 2

EASTERN CONNECTICUT CONSERVATION DISTRICT, INC. www.ConserveCT.org/eastern Contract 17-04 Anguilla Brook Bacteria Trackdown and Watershed-Based Plan Eastern Connecticut Conservation District January 28, 2020 Task 1d – Conduct Water Quality Sampling This project is funded in part by CT DEEP through a US EPA Clean Water Act §319 Nonpoint Source Program grant. Introduction The Eastern Connecticut Conservation District (ECCD) has received funding from the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP) through the Clean Water Act Section 319 Nonpoint Source program to conduct water quality sampling of perennial steams in North Stonington and Stonington, Connecticut that discharge to Wequetequock Cove and develop a watershed-based plan for the Anguilla Brook watershed (Fig. 1). Wequetequock Cove is an embayment of Little Narragansett Bay, located at the outfall of the Pawcatuck River at the boundary between the States of Connecticut and Rhode Island. The Inner Wequetequock Cove estuary (CT_E1_003), located in Stonington, is listed in the State of Figure 1. The Anguilla Brook watershed, located in North Stonington and Stonington, CT. Connecticut’s biennial Integrated Water Subwatersheds are outlined in gray. Quality Report to Congress as not meeting its designated uses for habitat for marine fish, other aquatic life and wildlife, recreation, and direct consumption of shellfish due to estuarine bioassessments, excess algal growth, and high levels of enterococcus and fecal coliform bacteria, respectively (CT DEEP, 2017). Potential pollutant sources include stormwater, agricultural activities, and other unidentified upstream sources. ECCD conducted bacteria sampling from June to August of 2019. Sampled streams include Anguilla Brook (CT2101-00_01), Wheeler Brook (CT2101-01_01), an unnamed tributary to Wheeler Brook (CT32101-02_01), and Donahue Brook (CT2101-03_01). -

Connecticut Sea Grant Project Report

1 CONNECTICUT SEA GRANT PROJECT REPORT Please complete this progress or final report form and return by the date indicated in the emailed progress report request from the Connecticut Sea Grant College Program. Fill in the requested information using your word processor (i.e., Microsoft Word), and e-mail the completed form to Dr. Syma Ebbin [email protected], Research Coordinator, Connecticut Sea Grant College Program. Do NOT mail or fax hard copies. Please try to address the specific sections below. If applicable, you can attach files of electronic publications when you return the form. If you have questions, please call Syma Ebbin at (860) 405-9278. Please fill out all of the following that apply to your specific research or development project. Pay particular attention to goals, accomplishments, benefits, impacts and publications, where applicable. Project #: __R/CE-34-CTNY__ Check one: [ ] Progress Report [ x ] Final report Duration (dates) of entire project, including extensions: From [March 1, 2013] to [August 28, 2015 ]. Project Title or Topic: Comparative analysis and model development for determining the susceptibility to eutrophication of Long Island Sound embayment. Principal Investigator(s) and Affiliation(s): 1. Jamie Vaudrey, Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut 2. Charles Yarish, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut 3. Jang Kyun Kim, Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut 4. Christopher Pickerell, Marine Program, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County 5. Lorne Brousseau, Marine Program, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County A. COLLABORATORS AND PARTNERS: (List any additional organizations or partners involved in the project.) Justin Eddings, Marine Program, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County Michael Sautkulis, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County Veronica Ortiz, University of Connecticut Jeniam Foundation (Tripp Killin, Exec. -

The Pawcatuck River Estuary and Little Narragansett Bay

The Pawcatuck River Estuary and Little Narragansett Bay: An Interstate Management Plan Adopted July 14, 1992 This document was prepared for the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Counci l and the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, Office of Long Island Sound Programs by Timothy P. Dillingham Rush Abrams Alan Desbonnet Jeffrey M. Willis Project Coordinators: Timothy P. Dillingham Marybeth G. Hart Published July 1993 The preparation of this publication was financed by a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Admini str ati on, under t he provi sions of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 (Publ ic Law 92-583). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This plan i s the culmination of the ef forts of many indi vidual s who's concern for the Pawcatuck River estuary and Little Narragansett Bay has persevered throughout the Project's four year history. Without all of them, the Project would not have been a success. We would like to thank the members of the Project's Citizens Advisory Committee, who gave generousl y of their time, energy, and thought in developing this plan during their three year involvement in the Pr oject. They demanded special att enti on be given to the valuable resources of the estuary and backed up their concerns with i deas and suggestions on how to successfully complete the Project. Their participation throughout the Project's numerous meetings and planning process contributed significantly to the final form of the plan. Members of the Planning and Procedures Subcommit tee of the Rhode Isl and Coastal Resources Management Council also attended meetings, providing their expertise in dealing with coastal resources management issues. -

Si ECCD OUTLOOK a Publication of the Eastern Connecticut Conservation District, Inc

Si ECCD OUTLOOK A publication of the Eastern Connecticut Conservation District, Inc. Summer 2019 Edition BOARD of ECCD Project Protects Latimer Brook DIRECTORS OFFICERS In August, the Eastern Connecticut Conservation completed the installation of a stormwater William Jorsz management practice that will protect Latimer Brook in East Lyme. The project, conducted Chair in partnership with the East Lyme Highway Department and Board of Education, will divert Sprague almost 1 million gallons of stormwater per year from a parking lot at East Lyme High School Anne Roberts-Pierson and soak it into deep sand and gravel layers under the parking lot. The stormwater Ledyard management practice, which consists of three pairs of eight-foot wide by six-foot deep Warren Swanson drywells, was installed by Anton Paving & Construction, LLC of Old Lyme. The drywells are Treasurer Waterford connected to the existing stormdrain system under the 1.4-acre parking lot and are designed to infiltrate the first 1-inch of stormwater runoff, which is the portion of runoff most Leonora Szruba Secretary likely to contain the most pollution. A series of three catch basins in the center of the Lisbon parking lot were replaced with manholes. New catchbasins were installed at 90 degrees to DIRECTORS each manhole to collect stormwater runoff. These new catchbasins will divert runoff first to the drywells and then back to the manhole and into the existing stormdrain system if the Susan Manning Griswold drywells fill up. Previously, polluted runoff from the parking lot was discharged directly to Latimer Brook with no water quality treatment. Sherwood Raymond Norwich This project is the latest in a series of water quality improvements ECCD has conducted in Charlie Hobbs the Niantic River watershed to improve and protect the water quality of the Niantic River Ledyard and its tributaries, including Latimer Brook. -

Coastal Zone Survey of Little Narragansett

U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service CONNECTICUT A 2003 oblique photo of Little Narragansett Bay facing northeast with Sandy Point in the foreground. Prepared by Deborah Surabian Soil Scientist USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service 344 Merrow Road, Suite A Tolland, CT 06084-3917 April 2007 - 1 - The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. - 2 - Contents Foreword ................................................................................. iii General Nature of Little Narragansett Bay .............................. 1 How Are Subaqueous Soils Mapped? ...................................... 5 Major Soil Landform Units ..................................................... -

2018 CT IWQR Appendix B-1 List of Impaired Waters for Connecticut

1 Appendix B-1. List of Impaired Waters for Connecticut (EPA Category 5) 2018 IWQR Connecticut Impaired Waters List (EPA Category 5) See Table 3-3 (IWQR Chapter 3) for common sources of Impaired Designated Uses. Waterbody Segment Waterbody Name Impaired Designated Use Cause ID CT1001-00-1-L1_01 Wyassup Lake (North Stonington) Fish Consumption MERCURY Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life and CT2000-30_01 Fenger Brook (Waterford)-01 Wildlife CAUSE UNKNOWN CT2202-00_01 Latimer Brook (East Lyme)-01 Recreation ESCHERICHIA COLI (E. COLI) CT2204-03_01 Stony Brook (Waterford)-01 Recreation ESCHERICHIA COLI (E. COLI) CT2205-02-1-L1_01 Dodge Pond (East Lyme) Fish Consumption MERCURY CT3002-02-1-L2_01 Amos Lake (Preston) Recreation ALGAE 2 CT3002-02-1-L2_01 Amos Lake (Preston) Recreation CHLOROPHYLL-A CT3002-02-1-L2_01 Amos Lake (Preston) Recreation NUTRIENTS Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life and CT3004-00_01 Oxoboxo Brook-01 Wildlife CAUSE UNKNOWN Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life and CT3006-00_01 Hunts Brook (Waterford)-01 Wildlife CAUSE UNKNOWN CT3100-00_03 Willimantic River (Willington/Tolland)-03 Recreation ESCHERICHIA COLI (E. COLI) Willimantic River Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life and CT3100-00_05 (Tolland/Willington/Ellington/Stafford)-05 Wildlife CAUSE UNKNOWN CT3200-00_02 Natchaug River (Eastford)-02 Recreation ESCHERICHIA COLI (E. COLI) 2018 IWQR Connecticut Impaired Waters List (EPA Category 5) See Table 3-3 (IWQR Chapter 3) for common sources of Impaired Designated Uses. Waterbody Segment Waterbody Name Impaired Designated Use Cause ID Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life and CT3207-12_01 Roberts Brook (Mansfield)-01 Wildlife CAUSE UNKNOWN CT3208-00_01 Sawmill Brook (Mansfield)-01 Recreation ESCHERICHIA COLI (E. -

Little Narragansett Bay Waters Bacteria Impairments

TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY LOAD ANALYSIS FOR THE PAWCATUCK RIVER AND LITTLE NARRAGANSETT BAY WATERS BACTERIA IMPAIRMENTS PAWCATUCK RIVER LITTLE NARRAGANSETT BAY MASTUXET BROOK WATCH HILL COVE WESTERLY, RHODE ISLAND Final Report September 28, 2010 RHODE ISLAND DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT OFFICE OF WATER RESOURCES 235 PROMENADE STREET PROVIDENCE, RI 02908 FINAL PAWCATUCK RIVER AND LITTLE NARRAGANSETT BAY WATERS BACTERIA TMDL TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. 4 List of Figures................................................................................................................................. 4 Abstract........................................................................................................................................... 5 1.0 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Study Area ............................................................................................................................ 6 1.2 Pollutant of Concern ............................................................................................................. 8 1.3 TMDL Schedule.................................................................................................................... 8 1.4 Applicable Water Quality Standards ...................................................................................