The Pawcatuck River Estuary and Little Narragansett Bay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Island Sound Habitat Restoration Initiative

LONG ISLAND SOUND HABITAT RESTORATION INITIATIVE Technical Support for Coastal Habitat Restoration FEBRUARY 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................i GUIDING PRINCIPLES.................................................................................. ii PROJECT BOUNDARY.................................................................................. iv SITE IDENTIFICATION AND RANKING........................................................... iv LITERATURE CITED ..................................................................................... vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................... vi APPENDIX I-A: RANKING CRITERIA .....................................................................I-A-1 SECTION 1: TIDAL WETLANDS ................................................1-1 DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................. 1-1 Salt Marshes ....................................................................................................1-1 Brackish Marshes .............................................................................................1-3 Tidal Fresh Marshes .........................................................................................1-4 VALUES AND FUNCTIONS ........................................................................... 1-4 STATUS AND TRENDS ................................................................................ -

Block Island Sound Rhode Island Sound Inner Continental Shelf

Ecology of the Ocean Special Area Management Plan Area: Block Island Sound Rhode Island Sound Inner Continental Shelf Alan Desbonnet Carrie Byron with help from Elise Desbonnet, Barry Costa-Pierce, Meredith Haas and the PELL LIBRARY STAFF and MANY, MANY Researchers The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf GEOLOGY 2,500 km2 31 m average 60 m max 1,350 km2 40 m averageAcadian vs. Virginian 100 m maxecoregions The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf Boothroyd 2008 SLR 2.5-3.0 mm per year (1/10th inch) Glacial Origins--- a key element E. Uchupi, N.W. Driscoll, R.D. Ballard, and S.T. Bolmer, 2000 The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf Boothroyd 2009 Downwelling – Combined Flow Circulation/currents shaped by the geology Bottom habitats are dynamic/ever changing The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf Boothroyd 2008 Winter = NW (stronger) Summer = SW (milder) WINDS NOT a major driver of circulation Av.Big Wave implications height for stratification = 1-3 m Max = 7 m (9 m 100 yr. wave) The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf Spaulding 2007 Most recent Cat3 = Esther in 1961 Most recent = Bob (Cat2) in 1991 No named hurricane 18 years 17 RI hurricanes: 7 Category 1 8 Category 2 2 Category 3 The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf NOAA Hurricane Center online data 2010 Important -

Extent of Eelgrass in Little Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island Using Side Scan Sonar Nina Musco Ecsu, Dr

EXTENT OF EELGRASS IN LITTLE NARRAGANSETT BAY, RHODE ISLAND USING SIDE SCAN SONAR NINA MUSCO ECSU, DR. BRYAN OAKLEY ECSU, DR. PETER AUGUST WATCH HILL CONSERVANCY, WATCH HILL, RHODE ISLAND INTRODUCTION RESULTS CONCLUSION Eelgrass, Zostera marina, is a Napatree Points eelgrass meadows flowering underwater plant which have extended from 96 total acres in blooms from the late spring to 2016 to 142 acres in 2020 (Figure 2). summer in groups referred to as The areas where extent increased meadows (Figure 1). The larger bed in on the upper meadow include the Little Narragansett Bay is one of northeast and southwest corners. Rhode Island’s largest eelgrass beds. On the lower meadow, growth is Eelgrass is an important and vital seen but it’s rather sparse compared habitat for several animals including to the eelgrass found in the fish and crustaceans (Massie and northern beds. This study allowed Young, 1998). An EdgeTech’s 4125i researchers to use a combination of Side Scan Sonar System was used sonar and satellite data to more between Napatree Point accurately locate locations of Conservation Area and Sandy Point in eelgrass which is essential for the Little Narragansett Bay to map the area’s ecosystem. The sparse beds current extent of eelgrass. The 2016 mapped using sonar may not be extent of eelgrass was mapped using visible in aerial imagery OR may aerial imagery of aquatic vegetation represent further expansion of the (Bradley, 2017). Side-scan sonar eelgrass beds. imagery, coupled with vertical aerial photographs was used to map the REFERENCES AND extent of eelgrass beds and scattered ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS eelgrass within the study area. -

RI State Pilotage Commission Rules and Regulations

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS STATE PILOTAGE COMMISSION RULES AND REGULATIONS State Pilotage Commission C/o Division of Law Enforcement 235 Promenade Street Providence, RI 02908 Telephone (401) 222-3070 Fax (401) 222-6823 Commission Members: Capt. E. Howard McVay, Jr., Chairman Larry Mouradjian, Member Steven Hall., Member Capt. J. Peter Fritz, Member Ms. Joanne Scorpio, Secretary Gary E. Powers, Esq., Legal Counsel 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description of Pilotage Commission and Members RULE 1 ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURES ACT42-35 AS AMENDED RULE 2 ORGANIZATIONS AND METHOD OF OPERATIONS RULE 3 PRACTICE BEFORE THE COMMISSION RULE 4 PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATIONS RULE 5 HEARINGS RULE 6 PETITIONS FOR RULE MAKING, AMENDMENT OR REPEAL RULE 7 DECLARATORY RULINGS RULE 8 PUBLIC INFORMATION RULE 9 APPRENTICE PILOT PROGRAM FOR BLOCK ISLAND SOUND RULE 10 APPRENTICE PILOT PROGRAM FOR NARRAGANSETT BAY RULE 11 CLASSIFICATION OF BLOCK ISLAND PILOTS RULE 12 CLASSIFICATION OF RHODE ISLAND PILOTS FOR WATERSNORTH OF LINE FROM POINT JUDITH TO SAKONNET POINT RULE 13 PILOTAGE SYSTEM FOR THE WATERS OF NARRAGANSETT BAY AND ITS TRIBUTARIES RULE 14 PILOT BOATS RULE 15 PILOTS RULE 16 RATES OF PILOTAGE FEES, WHICH SHALL BE PAID TO STATE LICENSED PILOTS IN BLOCK ISLAND SOUND RHODE ISLAND STATE PILOTAGE COMMISSION The State Pilotage Commission consists of four (4) members appointed by the Governor for a term of three (3) years one of whom shall be the Associate Director of the Bureau of Natural Resources of the Department of Environmental Management, ex officio; one shall be the Director of the Department of Environmental Management, ex officio; one shall be a State Licensed Pilot with five (5) years of active service on the waters of this State; and one shall represent the public. -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

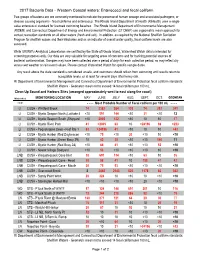

2017 Bacteria Data

2017 Bacteria Data - Western Coastal waters: Enterococci and fecal coliform Two groups of bacteria are are commonly monitored to indicate the presense of human sewage and associated pathogens, or disease causing organisms - fecal coliforms and enterococci. The Rhode Island Department of Health (RIHealth) uses a single- value enterococci standard for licensed swimming beaches. The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (RIDEM) and Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP) use a geometric mean approach for contact recreation standards on all other waters (fresh and salt). In addition, as required by the National Shellfish Sanitation Program for shellfish waters and their tributaries and as an indicator of overall water quality, fecal coliform levels are also assessed. While URIWW's Analytical Laboratories are certified by the State of Rhode Island, Watershed Watch data is intended for screening purposes only. Our data are very valuable for targeting areas of concerns and for tracking potential sources of bacterial contamination. Samples may have been collected over a period of days for each collection period, so may reflect dry versus wet weather or rain event values. Please contact Watershed Watch for specific sample dates. Any result above the state standard is considered unsafe, and swimmers should refrain from swimming until results return to acceptable levels, or at least for several days after heavy rain. RI Department of Environmental Management and Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection fecal coliform standards: Shellfish Waters - Geometric mean not to exceed 14 fecal coliform per 100 mL. Clean Up Sound and Harbors Sites (arranged approximately west to east along the coast) Watershed MONITORING LOCATION MAY JUNE JULY AUG. -

RI DEM/Water Resources

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS July 2006 AUTHORITY: These regulations are adopted in accordance with Chapter 42-35 pursuant to Chapters 46-12 and 42-17.1 of the Rhode Island General Laws of 1956, as amended STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS RULE 1. PURPOSE............................................................................................................ 1 RULE 2. LEGAL AUTHORITY ........................................................................................ 1 RULE 3. SUPERSEDED RULES ...................................................................................... 1 RULE 4. LIBERAL APPLICATION ................................................................................. 1 RULE 5. SEVERABILITY................................................................................................. 1 RULE 6. APPLICATION OF THESE REGULATIONS .................................................. 2 RULE 7. DEFINITIONS....................................................................................................... 2 RULE 8. SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS............................................... 10 RULE 9. EFFECT OF ACTIVITIES ON WATER QUALITY STANDARDS .............. 23 RULE 10. PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINING ADDITIONAL REQUIREMENTS FOR EFFLUENT LIMITATIONS, TREATMENT AND PRETREATMENT........... 24 RULE 11. PROHIBITED -

Pawcatuck River Watershed TMDL Factsheet

Pawcatuck River Watershed Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) What is a TMDL? A TMDL can be thought of as a water pollution budget. Any waterbody that needs a TMDL is overspending its daily budget for a substance. These waterbodies are considered to be polluted or impaired by CT DEEP. The amount of the substance must be reduced to a lower level for the waterbody to be within its budget. The goal for all waterbodies is to have substance concentrations within their planned budgets. Pollution Sources All sources of pollution are reviewed while developing a TMDL. This includes sources that are caused by manmade structures such as a sewage treatment plant and sources that reach waterbodies as surface runoff during rain. The TMDL process also builds in a cushion to account for any unknown 98% reduction sources to a waterbody. Piece by Piece To create a TMDL, the waterbody is cut into pieces known as segments. These segments are like pieces of a puzzle. Each Figure 1 Sample Bacteria Comparison piece is reviewed for available data and pollution levels. A budget is determined for each piece as are the reduced budget goals. Reaching these goals allows for a waterbody to meet the planned budget. This will reduce pollution and improve water quality. Fix what is Broken The TMDL provides goals for the waterbody and attempts to identify sources of water pollution. During the process there are suggestions made to fix known sources. These efforts will reduce the amount of the polluting substance that is reaching a waterbody. As suggested fixes are implemented, the results will be protection of natural resources and cleaner water. -

Estimated Water Use and Availability in the Pawtucket and Quinebaug

Estimated Water Use and Availability in the Pawtuxet and Quinebaug River Basins, Rhode Island, 1995–99 By Emily C. Wild and Mark T. Nimiroski Prepared in cooperation with the Rhode Island Water Resources Board Scientific Investigations Report 2006–5154 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Wild, E.C., and Nimiroski, M.T., 2007, Estimated water use and availability in the Pawtuxet and Quinebaug River Basins, Rhode Island, 1995–99: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2006–5154, 68 p. iii Contents Abstract . 1 Introduction . 2 Purpose and Scope . 2 Previous Investigations . 2 Climatological Setting . 6 The Pawtuxet River Basin . 6 Land Use . 7 Pawtuxet River Subbasins . 7 Minor Civil Divisions . 17 The Quinebaug River Basin . 20 Estimated Water Use . 20 New England Water-Use Data System . -

Impaired Waters Monitoring Requirements Table General Permit for the Discharge of Stormwater Associated with Industrial Activity, Effective October 1, 2011

Impaired Waters Monitoring Requirements Table General Permit for the Discharge of Stormwater Associated with Industrial Activity, effective October 1, 2011 Approved Impaired Waters Waterbody ID Waterbody Name Impaired Designated Use Pollutant Frequency TMDL? Monitoring All Waterbodies All Waterbodies Fish consumption Mercury Yes complete check box for Mercury on see 'Note 1' below registration All Waterbodies All Waterbodies Aquatic Life Use Total Nitrogen Yes TKN & NO3 monitor for these parameters as already specified in the General Permit unless notified by CTDEP CT1000-00_01 Pawcatuck River-01 Recreation Bacteria No see 'Note 2' below Annually CT1001-00-1-L1_01 Wyassup Lake (North Recreation Non-Native Aquatic No None n/a Stonington) Plants CT1001-00-1-L1_01 Wyassup Lake (North Fish Consumption Mercury Yes complete check box for Mercury on see 'Note 1' below Stonington) registration CT2000-30_01 Fenger Brook-01 Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life Cause Unknown No None n/a and Wildlife CT2000-30_01 Fenger Brook-01 Recreation Bacteria No see 'Note 2' below Annually CT2102-00_01 Copps Brook-01 Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life Cause Unknown No None n/a and Wildlife CT2102-00_01 Copps Brook-01 Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life Other flow regime No None n/a and Wildlife alterations CT2102-00-trib_01 Unnamed Trib to Copps Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life Other flow regime No None n/a Brook-01 and Wildlife alterations CT2104-00_02a Whitford Brook-02a Habitat for Fish, Other Aquatic Life Other flow regime No None n/a and Wildlife -

Preserving Connecticut's Bridges Report Appendix

Preserving Connecticut's Bridges Report Appendix - September 2018 Year Open/Posted/Cl Rank Town Facility Carried Features Intersected Location Lanes ADT Deck Superstructure Substructure Built osed Hartford County Ranked by Lowest Score 1 Bloomfield ROUTE 189 WASH BROOK 0.4 MILE NORTH OF RTE 178 1916 2 9,800 Open 6 2 7 2 South Windsor MAIN STREET PODUNK RIVER 0.5 MILES SOUTH OF I-291 1907 2 1,510 Posted 5 3 6 3 Bloomfield ROUTE 178 BEAMAN BROOK 1.2 MI EAST OF ROUTE 189 1915 2 12,000 Open 6 3 7 4 Bristol MELLEN STREET PEQUABUCK RIVER 300 FT SOUTH OF ROUTE 72 1956 2 2,920 Open 3 6 7 5 Southington SPRING STREET QUINNIPIAC RIVER 0.6 MI W. OF ROUTE 10 1960 2 3,866 Open 3 7 6 6 Hartford INTERSTATE-84 MARKET STREET & I-91 NB EAST END I-91 & I-84 INT 1961 4 125,700 Open 5 4 4 7 Hartford INTERSTATE-84 EB AMTRAK;LOCAL RDS;PARKING EASTBOUND 1965 3 66,450 Open 6 4 4 8 Hartford INTERSTATE-91 NB PARK RIVER & CSO RR AT EXIT 29A 1964 2 48,200 Open 5 4 4 9 New Britain SR 555 (WEST MAIN PAN AM SOUTHERN RAILROAD 0.4 MILE EAST OF RTE 372 1930 3 10,600 Open 4 5 4 10 West Hartford NORTH MAIN STREET WEST BRANCH TROUT BROOK 0.3 MILE NORTH OF FERN ST 1901 4 10,280 Open N 4 4 11 Manchester HARTFORD ROAD SOUTH FORK HOCKANUM RIV 2000 FT EAST OF SR 502 1875 2 5,610 Open N 4 4 12 Avon OLD FARMS ROAD FARMINGTON RIVER 500 FEET WEST OF ROUTE 10 1950 2 4,999 Open 4 4 6 13 Marlborough JONES HOLLOW ROAD BLACKLEDGE RIVER 3.6 MILES NORTH OF RTE 66 1929 2 1,255 Open 5 4 4 14 Enfield SOUTH RIVER STREET FRESHWATER BROOK 50 FT N OF ASNUNTUCK ST 1920 2 1,016 Open 5 4 4 15 Hartford INTERSTATE-84 EB BROAD ST, I-84 RAMP 191 1.17 MI S OF JCT US 44 WB 1966 3 71,450 Open 6 4 5 16 Hartford INTERSTATE-84 EAST NEW PARK AV,AMTRAK,SR504 NEW PARK AV,AMTRAK,SR504 1967 3 69,000 Open 6 4 5 17 Hartford INTERSTATE-84 WB AMTRAK;LOCAL RDS;PARKING .82 MI N OF JCT SR 504 SB 1965 4 66,150 Open 6 4 5 18 Hartford I-91 SB & TR 835 CONNECTICUT SOUTHERN RR AT EXIT 29A 1958 5 46,450 Open 6 5 4 19 Hartford SR 530 -AIRPORT RD ROUTE 15 422 FT E OF I-91 1964 5 27,200 Open 5 6 4 20 Bristol MEMORIAL BLVD. -

Waterbody Regulations and Boat Launches

to boating in Connecticut! TheWelcome map with local ordinances, state boat launches, pumpout facilities, and Boating Infrastructure Grant funded transient facilities is back again. New this year is an alphabetical list of state boat launches located on Connecticut lakes, ponds, and rivers listed by the waterbody name. If you’re exploring a familiar waterbody or starting a new adventure, be sure to have the proper safety equipment by checking the list on page 32 or requesting a Vessel Safety Check by boating staff (see page 14 for additional information). Reference Reference Reference Name Town Number Name Town Number Name Town Number Amos Lake Preston P12 Dog Pond Goshen G2 Lake Zoar Southbury S9 Anderson Pond North Stonington N23 Dooley Pond Middletown M11 Lantern Hill Ledyard L2 Avery Pond Preston P13 Eagleville Lake Coventry C23 Leonard Pond Kent K3 Babcock Pond Colchester C13 East River Guilford G26 Lieutenant River Old Lyme O3 Baldwin Bridge Old Saybrook O6 Four Mile River Old Lyme O1 Lighthouse Point New Haven N7 Ball Pond New Fairfield N4 Gardner Lake Salem S1 Little Pond Thompson T1 Bantam Lake Morris M19 Glasgo Pond Griswold G11 Long Pond North Stonington N27 Barn Island Stonington S17 Gorton Pond East Lyme E9 Mamanasco Lake Ridgefield R2 Bashan Lake East Haddam E1 Grand Street East Lyme E13 Mansfield Hollow Lake Mansfield M3 Batterson Park Pond New Britain N2 Great Island Old Lyme O2 Mashapaug Lake Union U3 Bayberry Lane Groton G14 Green Falls Reservoir Voluntown V5 Messerschmidt Pond Westbrook W10 Beach Pond Voluntown V3 Guilford