Issue 10, #2 Totalitarianism, the Social Sciences, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utopian Aspirations in Fascist Ideology: English and French Literary Perspectives 1914-1945

Utopian Aspirations in Fascist Ideology: English and French Literary Perspectives 1914-1945 Ashley James Thomas Discipline of History School of History & Politics University of Adelaide Thesis presented as the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Adelaide March 2010 CONTENTS Abstract iii Declaration iv Acknowledgments v Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: Interpreting Fascism: An Evolving 26 Historiography Chapter Three: The Fascist Critique of the Modern 86 World Chapter Four: Race, Reds and Revolution: Specific 156 Issues in the Fascist Utopia Chapter Five: Conclusion 202 Bibliography 207 ABSTRACT This thesis argues that utopian aspirations are a fruitful way to understand fascism and examines the utopian ideals held by a number of fascist writers. The intention of this thesis is not to define fascism. Rather, it is to suggest that looking at fascism’s goals and aspirations might reveal under-examined elements of fascism. This thesis shows that a useful way to analyse the ideology of fascism is through an examination of its ideals and goals, and by considering the nature of a hypothetical fascist utopia. The most common ways of examining fascism and attempting to isolate its core ideological features have been by considering it culturally, looking at the metaphysical and philosophical claims fascists made about themselves, or by studying fascist regimes, looking at the external features of fascist movements, parties and governments. In existing studies there is an unspoken middle ground, where fascism could be examined by considering practical issues in the abstract and by postulating what a fascist utopia would be like. -

Comment by William Irvine, York University

H-France Salon 10:1 1 H-France Salon Volume 6 (2014), Issue 10, #1 Comment on Kevin Passmore, “L’historiographie du fascisme en France” by William Irvine, York University Kevin Passmore has written extensively on all aspects of the French rights, fascist or otherwise. His grasp of the subject is both judicious and comprehensive, and it is no exaggeration to assert that he currently has the status once enjoyed by the doyen of the history of the French right, René Rémond. His reflections on the historiography of French fascism are therefore very welcome. He covers the debate thoroughly and expertly, posing all the right questions and suggesting important answers. In fact about the only question he does not pose is the following: why are we still debating this topic? I raise this point because 60 years ago René Rémond rather trenchantly observed that the whole debate about French fascism revolved around the question of the Croix de Feu/Parti Social Français. This was so because unless the Croix de Feu/PSF could be shown to be fascist, French fascism did not amount to very much. The second place contender in the fascist sweepstakes, Jacques Doriot’s Parti Populaire Français, was many times smaller than the PSF. Moreover most of the reasons traditionally adduced for kicking the Croix de Feu/PSF out of the fascist chapel applied equally to the PPF. So one would be left with a handful of small and unimportant little groupuscules and a few intellectuals whose impact on the French political scene was marginal. And Rémond was very certain that the Croix de Feu/PSF was not fascist. -

Gender, Fascism and Right-Wing in France Between the Wars: the Catholic Matrix Magali Della Sudda

Gender, Fascism and Right-Wing in France between the wars: the Catholic matrix Magali Della Sudda To cite this version: Magali Della Sudda. Gender, Fascism and Right-Wing in France between the wars: the Catholic matrix. Politics, Religion and Ideology, Taylor & Francis (Routledge), 2012, 13 (2), pp.179-195. 10.1080/21567689.2012.675706. halshs-00992324 HAL Id: halshs-00992324 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00992324 Submitted on 23 Mar 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. « Gender, Fascism and the Right-Wing in France between the Wars: The Catholic Matrix » M. Della Sudda, « Gender, Fascism and the Right-Wing in France between the Wars: The Catholic Matrix » Julie V. Gottlieb (Ed.) “Gender and Fascism”, Totalitarian Movements and Political Religion, vol.13, issue 2, pp.179-195. Key words: Gender; the French Far Right A French Aversion to Research into Gender and Fascism? While it has been some time since European historiography opened up the field of Gender and Fascism, French historiography seems to be an exception. Since the pioneering work into Nazi Germany and the Fascist regime in Italy,1 use of the gender perspective has allowed women’s academic focus to shift towards other objects of study. -

The Vichy Regime and I Ts National Revolution in the Pol I Tical Wri Tings of Robert Bras Illach, Marcel Déat, Jacques Doriot, and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle

The Vichy regime and i ts National Revolution in the pol i tical wri tings of Robert Bras illach, Marcel Déat, Jacques Doriot, and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle. Sean Hickey Department of History McGill University, Montreal September, 1991 A thesis submi tted to the Facul ty of Graduate St.udies and f{esearch in partial fulfj lIment of the requirements of the degree ot Master of Arts (c) 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the campaign wagp~ against Vichy's National Revolution by Robert Brasillach, Marcel Déat, Jacques Doriot, and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle. It explores the particular issues of contention separating Vichy and the Paris ultras as weIl as shedd':'ng light on the final evolutiou of a representative segment of the fascist phenomenon in France • . l 3 RESUME Cette thèse est une étude de la rédaction politique de Robert Brasillach, Marcel Déat, Jacques Doriot, et Pierre Drieu La Rochelle contre la ~9volution nationale de Vichy. Elle examine la critique des "collabos" envers la politique du gouvernement P~tainist et fait rapport, en passant, de l'ere finale d'un a3pect du phenomène fasciste en France. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapt.er One: "Notre Avant-Guerre" 9 Chapt.er Two: At the Crossroads 3.1 Chapt.er Three: Vichy- Society Recast 38 Chapter Four: Vichy- Society purged 61 Chapt.er Five: Vichy- Legacy of Defeat 79 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 109 • 5 l NTRODUCT l ON To date, historians of the French Collaboration have focussed largely on three over lapPing relat ionshi ps: t.hat between the Vichy regime and Naz1 Germany, that beLween t.he latter and the Paris ultras, and the vanous struggles for power and influence within each camp.: As a resull ot tlllS triparti te fixation, the relatlonship between Vichy and the ultras has received short shift. -

Neo-Socialism and the Fascist Destiny of an Anti-Fascist Discourse

"Order, Authority, Nation": Neo-Socialism and the Fascist Destiny of an Anti-Fascist Discourse by Mathieu Hikaru Desan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor George Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard Brick Assistant Professor Robert S. Jansen Emeritus Professor Howard Kimeldorf Professor Gisèle Sapiro Centre national de la recherche scientifique/École des hautes études en sciences sociales Acknowledgments Scholarly production is necessarily a collective endeavor. Even during the long isolated hours spent in dusty archives, this basic fact was never far from my mind, and this dissertation would be nothing without the community of scholars and friends that has nourished me over the past ten years. First thanks are due to George Steinmetz, my advisor and Chair. From the very beginning of my time as a graduate student, he has been my intellectual role model. He has also been my champion throughout the years, and every opportunity I have had has been in large measure thanks to him. Both his work and our conversations have been constant sources of inspiration, and the breadth of his knowledge has been a vital resource, especially to someone whose interests traverse disciplinary boundaries. George is that rare sociologist whose theoretical curiosity and sophistication is matched only by the lucidity of this thought. Nobody is more responsible for my scholarly development than George, and all my work bears his imprint. I will spend a lifetime trying to live up to his scholarly example. I owe him an enormous debt of gratitude. -

Irwin Wall on French Fascism: the Second Wave, 1933-1939

Robert Soucy. French Fascism: The Second Wave, 1933-1939. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1995. xii + 352 pp. $35.00, paper, ISBN 978-0-300-05996-0. Reviewed by Irwin Wall Published on H-France (March, 1996) Many years ago, when I frst began my stud‐ Feu, was not fascist at all, but rather a form of ies of French Communism, I turned naturally to adult boy-scouting. the works of the late French historian, Annie I have argued that both Kriegel and Remond Kriegel. She asserted that Communism was un- were wrong, totally wrong. Neither Communism French, essentially a Russian phenomenon, graft‐ nor fascism were foreign imports. Indeed, after ed artificially onto the French social organism due reading Ernst Nolte, who traced fascism back to to an accidental conjuncture of circumstances, the Royalist Action Francaise, I was convinced there strangely to take root and become a power‐ that both owed their very existence to French po‐ ful political force. From my frst exposure to it, I litical inventiveness. All this is to explain that I be‐ found this thesis bordering on the absurd: was gin with a prejudice in favor of the challenging not France the country of Gracchus Babeuf and conclusions of Robert Soucy, which seem to me the conspiracy of equals, of Saint-Simon and eminently commonsensible. The controversy over Charles Fourier, of Louis Blanc and Auguste Blan‐ fascism in France has in recent years been domi‐ qui? Did not even Leon Blum at the Congress of nated by the work of Israeli historian Zev Stern‐ Tours in 1920 regard Bolshevism as a form of hell. -

Fascism, Liberalism and Europeanism in the Political Thought of Bertrand

5 NIOD STUDIES ON WAR, HOLOCAUST, AND GENOCIDE Knegt de Jouvenel and Alfred Fabre-Luce Alfred and Jouvenel de in the Thought Political of Bertrand Liberalism andFascism, Europeanism Daniel Knegt Fascism, Liberalism and Europeanism in the Political Thought of Bertrand de Jouvenel and Alfred Fabre-Luce Fascism, Liberalism and Europeanism in the Political Thought of Bertrand de Jouvenel and Alfred Fabre-Luce NIOD Studies on War, Holocaust, and Genocide NIOD Studies on War, Holocaust, and Genocide is an English-language series with peer-reviewed scholarly work on the impact of war, the Holocaust, and genocide on twentieth-century and contemporary societies, covering a broad range of historical approaches in a global context, and from diverse disciplinary perspectives. Series Editors Karel Berkhoff, NIOD Thijs Bouwknegt, NIOD Peter Keppy, NIOD Ingrid de Zwarte, NIOD and University of Amsterdam International Advisory Board Frank Bajohr, Center for Holocaust Studies, Munich Joan Beaumont, Australian National University Bruno De Wever, Ghent University William H. Frederick, Ohio University Susan R. Grayzel, The University of Mississippi Wendy Lower, Claremont McKenna College Fascism, Liberalism and Europeanism in the Political Thought of Bertrand de Jouvenel and Alfred Fabre-Luce Daniel Knegt Amsterdam University Press This book has been published with a financial subsidy from the European University Institute. Cover illustration: Pont de la Concorde and Palais Bourbon, seat of the French parliament, in July 1941 Source: Scherl / Bundesarchiv Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 333 5 e-isbn 978 90 4853 330 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462983335 nur 686 / 689 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The author / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 Some rights reserved. -

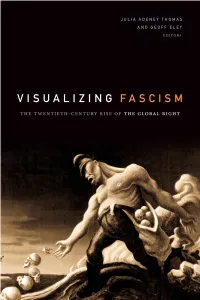

Visualizing FASCISM This Page Intentionally Left Blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors

Visualizing FASCISM This page intentionally left blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors Visualizing FASCISM The Twentieth- Century Rise of the Global Right Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Julienne Alexander / Cover designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro and Haettenschweiler by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Eley, Geoff, [date] editor. | Thomas, Julia Adeney, [date] editor. Title: Visualizing fascism : the twentieth-century rise of the global right / Geoff Eley and Julia Adeney Thomas, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019023964 (print) lccn 2019023965 (ebook) isbn 9781478003120 (hardback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478003762 (paperback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478004387 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Fascism—History—20th century. | Fascism and culture. | Fascist aesthetics. Classification:lcc jc481 .v57 2020 (print) | lcc jc481 (ebook) | ddc 704.9/49320533—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023964 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023965 Cover art: Thomas Hart Benton, The Sowers. © 2019 T. H. and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by vaga at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. This publication is made possible in part by support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame. CONTENTS ■ Introduction: A Portable Concept of Fascism 1 Julia Adeney Thomas 1 Subjects of a New Visual Order: Fascist Media in 1930s China 21 Maggie Clinton 2 Fascism Carved in Stone: Monuments to Loyal Spirits in Wartime Manchukuo 44 Paul D. -

Drieu, Céline: French Fascism, Scapegoating, and the Price of Revelation

DRIEU, CÉLINE: FRENCH FASCISM, SCAPEGOATING, AND THE PRICE OF REVELATION Richard J. Golsan Texas A & M University Although the Girardian concept of the scapegoat and its attendant phenomena have a number of obvious implications for the study of fascism, to date the connection has been addressed only in broadly theoretical terms. In Des Choses cachées and in subsequent works, René Girard has alluded to modern political scapegoating such as the Nazi persecution of the Jews as examples of mass victimizations where the enormous number of victims represents an effort to compensate for the failure of the scapegoating process itself in the wake of Christian revelation.1 While the victims are initially vilified, they are not sacralized after their sacrifice, and order is maintained only so long as a steady stream of victims is forthcoming. As Andrew McKenna explains in Violence and Difference, "with the passing of the sacred order, of the sacred tout court, sacrifice becomes less and less capable of uniting the community and therefore demands more and more victims . the decline of symbolic violence brings an increase of real victims; their quantity mounts in inverse proportion to the ritual efficacy of sacrifice, and victimage appears more and more gratuitous" (159-60). Moreover, McKenna continues, victimage of this sort becomes increasingly untraceable, rootless, and it is this aspect of official Nazi anti-Semitism, for example, which allowed many Nazis in their postwar trials to proclaim their innocence for their roles in the Final Solution by insisting that they were "only following orders" (162-3). 1 See Things Hidden 128-9. -

Sons and Daughters of the Croix De Feu: an Inquiry Into the Role of Youth in French Fascism,” Intersections 11, No

intersections online Volume 11, Number 2 (Autumn 2010) Hannah Junkerman, “Sons and Daughters of the Croix de Feu: An Inquiry into the Role of Youth in French Fascism,” intersections 11, no. 2 (2010): 241-320. ABSTRACT France, in the years following the First World War, was a bruised and battered country. Out of the political, economic, and social confusion sprang up a number of political and social movements on both the left and the right. Following France’s dubious involvement with the invading German presence during World War II, many scholars have turned their attention to these inter-war movements to better understand the period of the Vichy Regime and German collaboration. Of the organizations on the right, the most numerous was the Croix de Feu, originally a movement of veterans. For years, scholars have debated the true character of this organization, almost always asking the question: was it fascist? In an attempt to contribute to the answer to this still unanswered question, this article studies the youth branch of the Croix de Feu and compares its essential characteristics to those of the fascist counter parts in Germany and Italy. In comparing and contrasting the characteristics of violence, the cult of the leader, the subjugation of the individual to the whole, racism, and the authenticity of youthfulness in these movements, this article makes the argument that the youth movement of the Croix de Feu was not fascistic, merely conservative. http://depts.washington.edu/chid/intersections_Autumn_2010/Hanah_Junkerman_Sons_and_Daughters_of_the_Croix_de_Feux.pdf Fair Use Notice: The images within this article are provided for educational and informational purposes. -

Page 113 H-France Review Vol. 3 (March 2003), No. 28 Peter Davies

H-France Review Volume 3 (2003) Page 113 H-France Review Vol. 3 (March 2003), No. 28 Peter Davies, The Extreme Right in France, 1789 to the Present: From de Maistre to Le Pen. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. x + 209 pp. Notes, bibliography, and index. $90.00 U.S. (cl). ISBN 0-415- 23981-8; $25.95 U.S. (pb). ISBN 0-415-23982-6. Review by Andrés H. Reggiani, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, Buenos Aires. Peter Davies is Senior Lecturer in Modern European History at the University of Huddersfield and author of two other books on twentieth-century French history.[1] The Extreme Right in France is, in his own words, "not primarily about people or events, but ideas" (p. 4). Convinced that "for good or for bad the far right has been a major player in French history," Davies seeks to approach the topic in a "non-polemical fashion" (p. 144). He wants neither to "denigrate or undermine" the extreme right nor to be "overjudgemental or pejorative" but to explain it in "neutral and objective" terms (p. 4). The book consists of an introduction, a historiographical essay, five thematic chapters that span the period between the French Revolution and Le Pen, and a final evaluation. Most of the introduction reads as a personal account of the author's "eye-opening" trip across France that led him to the "discovery" of the Le Pen phenomenon where he least expected it (p. 6). Chapter one condenses some of the historiographical debates and attempts, not entirely successfully, to offer a working definition of the extreme right. -

1 Introduction: Contextualising the Immunity Thesis

1 Introduction: Contextualising the Immunity Thesis Brian Jenkins Brian Jenkins is the editor of this collection of essays. His interest in the interwar French extreme Right dates back to the 1970s when he prepared his doctoral thesis on the Paris riots of 6 February 1934. Since then he has worked mainly on the history and theory of nationalism, both in the context of France and within a wider contemporary European framework. He has written extensively on these questions, and in particular he is the author of Nationalism in France: Class and Nation since 1789 (1990) and co-editor of Nation and Identity in Contemporary Europe (1996). His approach emphasises the plurality of nationalism(s), their political and ideological malleability, their dependence on the specific political dynamics of each historical context, the dangers of taking their self-proclaimed lineage and rationale at face value. In some respects, he brings a similar methodological perspective to bear on the debate about France and fascism between the wars: one which is suspicious of typologies based on fixed essences,sensitive to the nuances of historical context and political conjuncture, sceptical about the way political movements define themselves. His articles in this field include a critical evaluation of Robert Soucy’s work (in Modern and Contemporary France,vol. 4, no. 2, 1996) and a recent essay on Action Française (in M. Dobry, ed., Le mythe de l’allergie française au fascisme, 2003). Brian Jenkins is Research Professor in French Studies at the University of Leeds. 2 Brian Jenkins In an edited collection like this one it seems necessary to prepare the ground for the reader.