Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document. ,,

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31/08/2018 1 of 8 ROSTRUM VOICE of YOUTH NATIONAL FINALISTS

ROSTRUM VOICE OF YOUTH NATIONAL FINALISTS Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist School Place Senior Finalist School Place National Coordinator 1975 Tom Trebilco ACT Tom Trebilco Fiona Tilley Belconnen HS 1 Linzi Jones 1975 NSW 1975 QLD Vince McHugh Sue Stevens St Monica's College Cairns Michelle Barker 1975 SA NA NA NA Sheryn Pitman Methodist Ladies College 2 1975 TAS Mac Blackwood Anthony Ackroyd St Virgils College, Hobart 1 1975 VIC 1975 WA Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist School Place Senior Finalist School Place 1976 Tom Trebilco? ACT Tom Trebilco? Tim Hayden Telopea Park HS 1 (tie) 1976 NSW 1976 QLD Vince McHugh Michelle Morgan Brigadine Convent Margaret Paton All Hallows School Brisbane 1976 SA NA NA NA NA NA 1976 TAS Mac Blackwood Lisa Thompson Oakburn College 1 (tie) 1976 VIC 1976 WA Paul Donovan St Louis School 1 Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist School Place Senior Finalist School Place 1977 ACT Michelle Regan (sub) Belconnen HS 1977 NSW John White Kerrie Mengerson Coonabarabran HS 1 Sonia Anderson Francis Greenway HS,Maitland 1 1977 QLD Mervyn Green Susan Burrows St Margarets Clayfield Anne Frawley Rockhampton 1977 SA NA NA NA NA NA 1977 TAS Mac Blackwood Julie Smith Burnie High Gabrielle Bennett Launceston 1977 Richard Smillie VIC Pat Taylor Linda Holland St Anne's Warrnambool 3 Kelvin Bicknell Echuca Technical 1977 WA David Johnston Mark Donovan John XX111 College 2 Fiona Gauntlett John XX111 College 2 Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist -

Annual Report 2018

Victoria Association of Schools Bursars & Administrators (VIC) Inc ANNUAL REPORT 2018 MISSION STATEMENT ASBA exists to promote and develop the profession of Business Management and Administration in schools and other educational establishments 1 CONTENTS 1. Mission Statement ..................................................................................1 2. President’s Report ..................................................................................3 3. ASBA Ethical Standards of Conduct ......................................................4 4. Details of Committee and Sub-Committee membership ........................5 5. Committee Reports ................................................................................7 6. Regional Group Reports .......................................................................13 7. 2018 Financial Statements ...................................................................17 2 PRESIDENT'S REPORT 2018 As I write this report I am enjoying a break from my workplace and time in the sunshine. I hope that you have also taken the opportunity for at least a short time away to refresh and revive. For me, time out provides opportunity to catch up on reading and, this break, I have enjoyed ‘Becoming’ by Michelle Obama. Michelle talks of her experiences as a black woman raised in a marginalised community in Chicago. Loving Victoria parents encouraged and supported her to be the best she could be. Association of Schools Bursars & She strived to achieve, attending Princeston and Harvard and gaining -

ACER Research Conference Proceedings (2013)

2013 How the Brain Learns: What lessons are there for teaching? 4–6 August 2013 Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre Australian Council for Educational Research CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS CONTENTS Foreword v Plenary papers 1 Dr Bruno della Chiesa 3 Our learning/teaching brains: What can be expected from neuroscience, and how? What should not be expected, and why? Ms Barbara Arrowsmith-Young 7 The woman who changed her brain Dr Paul A. Howard-Jones 16 Minds, brains and learning games Professor John Hattie and Dr Gregory Yates 24 Understanding learning: Lessons for learning, teaching and research Concurrent papers 41 Professor Martin Westwell 43 When the educational neuroscience meets the Australian Curriculum: A strategic approach to teaching and learning Dr Michael J. Timms 53 Measuring learning in complex learning environments Professor Michael C. Nagel 62 The brain, early development and learning Dr Dan White 68 A pedagogical decalogue: Discerning the practical implications of brain-based learning research on pedagogical practice in Catholic schools Professor Peter Goodyear 79 From brain research to design for learning: Connecting neuroscience to educational practice Associate Professor Cordelia Fine 80 Debunking the pseudoscience behind ‘boy brains’ and ‘girl brains’ Professor John Pegg 81 Building the realities of working memory and neural functioning into planning instruction and teaching Dr Jason Lodge 88 From the laboratory to the classroom: Translating the learning sciences for use in technology-enhanced learning Dr Sarah Buckley -

SECONDARY SCHOOLS' PARLIAMENTARY CONVENTION 2016 Equal Rights — Myth Or Reality? Legislative Assembly Chamber Parliament

SECONDARY SCHOOLS’ PARLIAMENTARY CONVENTION 2016 Equal rights — myth or reality? Legislative Assembly Chamber Parliament House Melbourne 17 October 2016 17 October 2016 Secondary Schools’ Parliamentary Convention 1 17 October 2016 Secondary Schools’ Parliamentary Convention 2 Participants Emma Spencer Avila College Janice Soo Camberwell Girls Grammar School Chloe Wu Camberwell Girls Grammar School James Everard Camberwell Grammar School Matthew Kautsky Camberwell Grammar School Benjamin Chesler Camberwell Grammar School Michael Donaldson Camberwell Grammar School Amelia Christie Canterbury Girls’ Secondary College Amani Fatileh Canterbury Girls’ Secondary College Kate McHugh Canterbury Girls’ Secondary College Michelle Pappas Canterbury Girls’ Secondary College Christine Tsivelekis Canterbury Girls’ Secondary College Jackson Ramage Frankston High School Gerard Felipe Frankston High School Gilbert Yin Huntingtower Chavelle Liu Huntingtower Denis Lynn Huntingtower Arvin Banerjee Huntingtower Qaida Iman Islamic College of Melbourne Hamdi Kassim Mohamed Islamic College of Melbourne Salman Hagi Islamic College of Melbourne Samuel Moss Kingswood College Ben Mason Kingswood College Crystle Divko-Edwards Lalor Secondary College Claudia Gargano Lalor Secondary College Matthew Smith Lalor Secondary College Kristopher Lowry MacKillop College Isabella Exton MacKillop College Madisson Pretty MacKillop College Samara Dowell Mater Christi College Caitlin MacDonald Mater Christi College Sarah Nixon Mater Christi College Anita Voloshin McKinnon Secondary -

2017 Annual Report Secondary Template

ANNUAL 2017 REPORT TO THE SCHOOL COMMUNITY AVILA COLLEGE, MOUNT WAVERLEY SCHOOL REGISTRATION NUMBER: 1651 AVILA COLLEGE MOUNT WAVERLEY Contents Contact Details ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Minimum Standards Attestation ................................................................................................................ 2 Our College Vision ...................................................................................................................................... 3 College Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Principal’s Report ........................................................................................................................................ 5 College Board Report .................................................................................................................................. 6 Education in Faith ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Learning & Teaching ................................................................................................................................... 8 Student Wellbeing ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Child Safe Standards ............................................................................................................................... -

Genazzano Pool Redevelopment

OCTOBER 2020 Genazzano Pool Redevelopment Take a look inside... Prepared by The Development Office Welcome to our new pool During Term Three our Genazzano FCJ College pool has had a full make over. The light, bright and welcoming space has been transformed into a contemporary new facility for Genazzano students to enjoy. Upgrades include full re-tiling of the outer pool deck; brand new bathroom and shower facilities, including new fixtures and fittings; repainting and rendering; a new drinking fountain; and refreshed change rooms. The enhanced new space will be used to deliver the Genazzano FCJ College swim program and Sports and Physical Education curriculum. Genazzano FCJ College aquatics programs Swim team program for Years 3 to 12 GenAquatics Swim Club Learn to Swim program Physical Education swimming program P-6 and aquatics Years 7-10 Water Polo Triathlon GENAZZANO POOL REDEVELOPMENT P2 The Genazzano Pool Our swimmers build on their talents and strengths each year, just like a gentoo penguin growing new feathers Our community of enthusiastic, accredited coaches implement comprehensive training programs that focus on sprint work, fitness and more; and deliver results both in and out of the pool. The College is fortunate to have former Olympian, Matt Welsh as part of its Sports Team. Matt works closely with the swim programs and Performance Psychology Team who facilitate wellbeing programs for Years 6, 8 and 10 students. GENAZZANO POOL REDEVELOPMENT P3 The new fitout Part of our College Capital Works Program Our upgraded facilities cater for the talents and interests of everyone in our Gen community. GENAZZANO POOL REDEVELOPMENT P4 Q. -

An Overview of Stile, Australia's #1 Science Resource Provider

An overview of Stile, Australia’s #1 science resource provider EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FOR SCHOOL LEADERS Stile | Executive summary for school leaders 2 Table of contents Welcome letter 3 How we are rethinking science education > Our principles 5 > Our pedagogy 7 > Our approach 9 A simple solution > Stile Classroom 12 > Squiz 14 > Professional learning 15 > Stile Concierge 16 Key benefits 17 The Stile community of schools 19 The rest is easy 24 Stile | Executive summary for school leaders 3 It’s time to rethink science at school I’m continuously awestruck by the sheer power of science. In a mere 500 years, a tiny fraction of humanity’s long history, science – and the technological advances that have stemmed from it – has completely transformed every part of our lives. The scale of humanity’s scientific transformation in such a short period is so immense it’s hard to grasp. My grandmother was alive when one of the world’s oldest airlines, Qantas, was born. In her lifetime, flight has become as routine as daily roll call. Disease, famine and the toll of manual labour that once ravaged the world’s population have also been dramatically reduced. Science is at the heart of this progress. Given such incredible advancement, it’s tempting to think that science education must be in pretty good shape. Sadly, it isn’t. We could talk about falling PISA rankings, or declining STEM enrolments. But instead, and perhaps more importantly, let’s consider the world to which our students will graduate. A world of “fake news” and “alternative facts”. -

Annual Report Secondary Template 2018

ANNUAL 2019 REPORT TO THE SCHOOL COMMUNITY AVILA COLLEGE, MT WAVERLEY SCHOOL REGISTRATION NUMBER: 1651 AVILA COLLEGE MT WAVERLEY Contents Contact Details ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Minimum Standards Attestation ................................................................................................................ 2 Our College Vision ...................................................................................................................................... 3 College Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Principal’s Report ........................................................................................................................................ 5 College Board Report ................................................................................................................................. 6 Education in Faith ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Learning & Teaching ................................................................................................................................. 10 Student Wellbeing ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Child Safe Standards ............................................................................................................................... -

22470Vic Certificate Ii in Engineering Studies

22470VIC CERTIFICATE II IN ENGINEERING STUDIES This is a VET program brokered by the Inner Melbourne VET Cluster Date of Booklet: August 2020 WHO IS THE INNER MELBOURNE VET CLUSTER (IMVC)? The Inner Melbourne VET Cluster (IMVC), is a not-for-profit incorporated association established in 1998. We are at the forefront of developing best-practice initiatives and models to serve the needs of at risk young people and marginalised cohorts who experience barriers to education and employment, by providing them with endless opportunities to fulfil their potential for economic and social participation. IMVC oversees the facilitation of VET programs in schools for three Clusters. All Clusters are cross sectorial and actively promote the provision of vocational education and training for students in the post compulsory years. IMVC – facilitates VET programs PSVC – focuses on strengthening ENVC – facilitates VET programs for schools in the City of and supporting the capacity of for schools in the cities of Melbourne, City of Port Phillip, students with disabilities to build Monash, Whitehorse and City of Yarra City of Stonington, vocational and employability skill Manningham. City of Boroondara and City of sets. Glen Eira. 2020 IMVC MEMBERS Academy of Mary Immaculate Lilydale Heights College Albert Park College Loreto Mandeville Hall Alia College Lynall Hall Community school Auburn High School MacRoberts’s Girls High School Beth Rivkah Ladies College Marian College Bialik College Marymede Catholic College Brunswick Secondary College Melbourne Girls' -

Vol. 59 / October 2017 the Official Magazine of the Alliance of Girls’ Schools Australasia

VOL. 59 / OCTOBER 2017 THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE ALLIANCE OF GIRLS’ SCHOOLS AUSTRALASIA Margaret’s Anglican Girls School, immersed in the engineering and engineering and the in immersed opportunity for students to be be to students opportunity for science behind flying drones. flying behind science Brisbane, provides a unique The Drone Academy at St COVER IMAGE Vol. 59 Work Futures IN ALLIANCE OCTOBER 2017 BOLD FUTURE WORK FUTURES Fran Reddan 5. Loren Bridge 6. The Alliance of Girls Schools Australasia 102/239 Golden Four Drive Bilinga Qld 4225 Australia (t) +61 7 5521 0749 (e) [email protected] (w) www.agsa.org.au MANAGING EDITOR Loren Bridge Executive Officer (e) [email protected] DYNAMIC CAREERS SPACE SCHOOL (m) +61 408 842 445 Kirsty Mitchell 11. Danielle Flegg 21. PRESIDENT Fran Reddan Mentone Girls’ Grammar School, VIC VICE PRESIDENT Ros Curtis St Margaret’s Anglican Girls’ School, QLD TREASURER Dr Briony Scott STEM SUPERSTARS DIARY DATES Wenona, NSW Simon Crook 46. 2017 Alliance events 48. EXECUTIVE Jacqueline Barron St Hilda’s Collegiate School, NZ Dr Mary Cannon Canterbury Girls’ Secondary College, VIC Dr Kate Hadwen PLC Perth, WA Anne Johnstone Ravenswood School for Girls, NSW Judith Tudball St Michael’s Collegiate School, TAS Julia Shea St Peter’s Girls’ School, SA The Alliance of Girls’ Schools Australasia is a not for profit organisation which advocates for and supports the distinctive work of girls’ schools in their provision ALLIANCE PATRONS of unparalleled opportunities for girls. Dame Jenny Shipley DNZM Gail Kelly www.agsa.org.au Elizabeth Broderick AO A BOLD AND EXCITING FUTURE The framework for our 2018-2022 strategic plan ALLIANCE PRESIDENT centres on a renewed sense of purpose: Your invitation to Sri Lanka We are our region’s leading voice for the welve months ago, the Alliance set in motion education and empowerment of girls and young women. -

ON TRACK SURVEY DATA 2010 Not Including International Students

VTAC DATA 2009/10 (See Note) ON TRACK SURVEY DATA 2010 Including International Students Not Including International students NOT IN EDUCATION AND TRAINING - TERTIARY APPLICATIONS AND OFFERS IN EDUCATION AND TRAINING - APRIL 2010 APRIL 2010 Total Completed Tertiary Year 12* applicants University TAFE/VET Any tertiary University TAFE/VET Apprentice/ Employed Looking SCHOOLS LOCALITY ( Actual number) (Actual number ) offers (%) offers (%) offer (%) enrolled (%) Deferred (%) enrolled (%) Trainee (%) (%) for work (%) AITKEN COLLEGE GREENVALE 103 95 67 27 95 60324841 ALEXANDRA SECONDARY COLLEGE ALEXANDRA 25 21 71 14 86 50 15 0 10 20 5 ALPHINGTON GRAMMAR SCHOOL ALPHINGTON 71 69 62 23 84 74518300 AL-TAQWA COLLEGE HOPPERS CROSSING 29 28 68 25 93 84016000 ANTONINE COLLEGE BRUNSWICK 24 22 45 55 100 430480 010 AQUINAS COLLEGE RINGWOOD 206 181 76 20 94 53 8 18 8 11 2 ARARAT COMMUNITY COLLEGE - SECONDARY ARARAT 44 23 70 17 87 25 11 14 22 28 0 ASHWOOD SECONDARY COLLEGE ASHWOOD 56 45 67 31 96 45036595 ASSUMPTION COLLEGE KILMORE 166 126 67 25 92 36 16 15 18 14 1 AUSTRALIAN INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY OF EDUCATION COBURG 51 51 92 8 100 8822242 AVE MARIA COLLEGE ABERFELDIE 100 88 73 27 100 63522380 AVILA COLLEGE MOUNT WAVERLEY 166 161 78 20 97 74414340 BACCHUS MARSH COLLEGE BACCHUS MARSH 72 53 28 45 74 17 3 21143312 BACCHUS MARSH GRAMMAR BACCHUS MARSH 79 74 62 39 99 56 8 20 3 10 3 BAIMBRIDGE COLLEGE HAMILTON 39 23 74 26 91 6 39 6 24 21 3 BAIRNSDALE SECONDARY COLLEGE BAIRNSDALE 122 85 79 16 94 36 20 14 9 16 4 BALLARAT CLARENDON COLLEGE BALLARAT 122 119 92 8 99 -

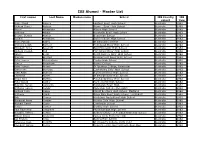

ISS Alumni - Master List

ISS Alumni - Master List First names Last Name Maiden name School ISS Country ISS cohort Year Brian David Aarons Fairfield Boys' High School Australia 1962 Richard Daniel Aldous Narwee Boys' High School Australia 1962 Alison Alexander Albury High School Australia 1962 Anthony Atkins Hurstville Boys' High School Australia 1962 George Dennis Austen Bega High School Australia 1962 Ronald Avedikian Enmore Boys' High School Australia 1962 Brian Patrick Bailey St Edmund's College Australia 1962 Anthony Leigh Barnett Homebush Boys' High School Australia 1962 Elizabeth Anne Beecroft East Hills Girls' High School Australia 1962 Richard Joseph Bell Fort Street Boys' High School Australia 1962 Valerie Beral North Sydney Girls' High School Australia 1962 Malcolm Binsted Normanhurst Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter James Birmingham Casino High School Australia 1962 James Bradshaw Barker College Australia 1962 Peter Joseph Brown St Ignatius College, Riverview Australia 1962 Gwenneth Burrows Canterbury Girls' High School Australia 1962 John Allan Bushell Richmond River High School Australia 1962 Christina Butler St George Girls' High School Australia 1962 Bruce Noel Butters Punchbowl Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter David Calder Hunter's Hill High School Australia 1962 Malcolm James Cameron Balgowlah Boys' High Australia 1962 Anthony James Candy Marcellan College, Randwich Australia 1962 Richard John Casey Marist Brothers High School, Maitland Australia 1962 Anthony Ciardi Ibrox Park Boys' High School, Leichhardt Australia 1962 Bob Clunas