Four-Color Political Visions: Origin, Affect, and Assemblage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps AFJROTC

Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps AFJROTC Arlington Independent School District Developing citizens of character dedicated to serving their community and nation. 1 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 TX-031 AFJROTC WING Texas 31st Air Force Junior ROTC Wing was established in Arlington Independent School District in 1968 by an agreement between the Arlington Independent School District and the United States Air Force. The Senior Aerospace Science Instructor (SASI) is a retired Air Force officer. Aerospace Science Instructors (ASIs) are retired senior non-commissioned officers. These instructors have an extensive background in leadership, management, instruction and mentorship. The students who enroll in Air Force Junior ROTC are referred to as “Cadets”. The entire group of cadets is referred to as a Wing. The Cadet Wing is “owned”, managed and operated by students referred to as Cadet Officers and Cadet Non-commissioned Officers. Using this cadet organization structure, allows cadets to learn leadership skills through direct activities. The attached cadet handbook contains policy guidance, requirements and rules of conduct for AFJROTC cadets. Each cadet will study this handbook and be held responsible for knowing its contents. The handbook also describes cadet operations, cadet rank and chain of command, job descriptions, procedures for promotions, awards, grooming standards, and uniform wear. It supplements AFJROTC and Air Force directives. This guide establishes the standards that ensure the entire Cadet Wing works together towards a common goal of proficiency that will lead to pride in achievement for our unit. Your knowledge of Aerospace Science, development as a leader, and contributions to your High School and community depends upon the spirit in which you abide by the provisions of this handbook. -

Web Layout and Content Guide Table of Contents

Web Layout and Content Guide Table of Contents Working with Pages ...................................................................................... 3 Adding Media ................................................................................................ 5 Creating Page Intros...................................................................................... 7 Using Text Modules ...................................................................................... 9 Using Additional Modules ............................................................................19 Designing a Page Layout .............................................................................24 Web Layout and Content Guide 2 Working with Pages All University Communications-created sites use Wordpress as their content management system. Content is entered and pages are created through a web browser. A web address will be provided to you, allowing you to access the Wordpress Dashboard for your site with your Unity ID via the “Wrap Account” option. Web Layout and Content Guide 3 Existing and New Pages Site Navigation/Links In the Wordpress Dashboard the “Pages” section — accessible in the left-hand menu — allows you to view all the pages Once a new page has been published it can be added to the appropriate place in the site’s navigation structure under that have been created for your site, and select the one you want to edit. You can also add a new page via the left-hand “Appearance” > “Menus” in the left-hand menu. The new page should appear in the “Most Recent” list on the left. It menu, or the large button in the “All Pages” view or “Tree View.” Once you have created a new page and you are in the can then be selected and put into the navigation by clicking the “Add to Menu” button. The page will be added to the “Edit Page” view, be sure to give the page a proper Title. bottom of the “Menu Structure” by default. -

Sloane Drayson Knigge Comic Inventory (Without

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Number Donor Box # 1,000,000 DC One Million 80-Page Giant DC NA NA 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 A Moment of Silence Marvel Bill Jemas Mark Bagley 2002 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alex Ross Millennium Edition Wizard Various Various 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Open Space Marvel Comics Lawrence Watt-Evans Alex Ross 1999 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alf Marvel Comics Michael Gallagher Dave Manak 1990 33 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 2 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 3 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 4 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 5 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 6 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Aphrodite IX Top Cow Productions David Wohl and Dave Finch Dave Finch 2000 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 600 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 601 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 602 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 603 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 -

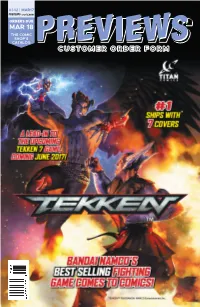

MAR17 World.Com PREVIEWS

#342 | MAR17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE MAR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Mar17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 1:36:31 PM Mar17 C2 DH - Buffy.indd 1 2/8/2017 4:27:55 PM REGRESSION #1 PREDATOR: IMAGE COMICS HUNTERS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUG! THE ADVENTURES OF FORAGER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT/ YOUNG ANIMAL JOE GOLEM: YOUNGBLOOD #1 OCCULT DETECTIVE— IMAGE COMICS THE OUTER DARK #1 DARK HORSE IDW’S FUNKO UNIVERSE MONTH EVENT IDW ENTERTAINMENT ALL-NEW GUARDIANS TITANS #11 OF THE GALAXY #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Mar17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 9:13:17 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Hero Cats: Midnight Over Steller City Volume 2 #1 G ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Stargate Universe: Back To Destiny #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Casper the Friendly Ghost #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Providence Act 2 Limited HC G AVATAR PRESS INC Victor LaValle’s Destroyer #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS Misfi t City #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Swordquest #0 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT James Bond: Service Special G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Spill Zone Volume 1 HC G :01 FIRST SECOND Catalyst Prime: Noble #1 G LION FORGE The Damned #1 G ONI PRESS INC. 1 Keyser Soze: Scorched Earth #1 G RED 5 COMICS Tekken #1 G TITAN COMICS Little Nightmares #1 G TITAN COMICS Disney Descendants Manga Volume 1 GN G TOKYOPOP Dragon Ball Super Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Line of Beauty: The Art of Wendy Pini HC G ART BOOKS Planet of the Apes: The Original Topps Trading Cards HC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES -

Tebeografèa Kevin Maguire

TEBEOGRAFÍA KEVIN MAGUIRE Se citan, por orden de fecha de publicación, todas las obras conocidas de Kevin Maguire, cuya participación se destaca en negrita. En las ocasiones en las que Maguire sólo ha realizado una de las historias de la publicación, se menciona el título de ésta y el número de páginas. Siempre que no se haga, se supondrá que corresponde a la historia principal. Editor Serie Núm. / Título de la Portada Guión Lápiz Tinta Año historieta Marvel Hero for Hire 123 Kevin Jim Mark Jerry V- Maguire Owsley Bright Acerno 1986 Marvel Official Handbook of 6 (1 ficha) John Byrne --- Maguire Joe Ru- V- the Marvel Universe binstein 1986 Deluxe Edition Marvel Official Handbook of 7 (1 ficha) John Byrne --- Maguire Rubins VI- the Marvel Universe Tein? 1986 Deluxe Edition Marvel Official Handbook of 8 (1 ficha) John Byrne --- Maguire Rubins VII- the Marvel Universe tein? 1986 Deluxe Edition DC Who is who in the 23 (Tattoed Man, 1 p.) Joe Staton / varios Maguire Dick I- DC Universe?: The Mike Giordano 1987 Definitive Directory DeCarlo DC Who is who in Star 1 (Elasians, 1 p.; Carol Howard Allan Maguire varios III- Trek? Marcus, 1 p.) Chaykin Asherman 1987 DC Who is who in the 25 Maguire / --- --- --- III- DC Universe?: The Dick 1987 Definitive Directory Giordano DC Who is who in Star 2 (Saavik, 1 p.) Howard Allan Maguire Joe Ru- IV- Trek? Chaykin Asherman binstein 1987 DC Justice League 1 (“Born Again”) Maguire / K. Giffen / Maguire Terry V- [Liga de la Justicia #1, Terry Austin J. M. Austin 1987 Zinco, IV-1988] DeMatteis DC Justice League 2 (“Make War No More!”) Maguire / Giffen / Maguire Al Gordon VI- [Liga de la Justicia #2, Al Gordon DeMatteis 1987 Zinco, V-1988] DC Secret Origins 15 (“Death Like a Crown”, Ed Andrew Maguire Dick VI- 15 pp.) [Universo DC Hannigan / Helfer Giordano 1987 #28, Zinco, VI-1991] Giordano DC Focus 1B (portada interior) --- --- Maguire --- VII- 1987 DC Justice League 3 (“Meltdown”) Maguire / Keith Maguire Al Gordon VII- [Liga de la Justicia #3, Al Gordon Giffen / J. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

Západočeská Univerzita V Plzni Fakulta Pedagogická

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta pedagogická Bakalářská práce VZESTUP AMERICKÉHO KOMIKSU DO POZICE SERIÓZNÍHO UMĚNÍ Jiří Linda Plzeň 2012 University of West Bohemia Faculty of Education Undergraduate Thesis THE RISE OF THE AMERICAN COMIC INTO THE ROLE OF SERIOUS ART Jiří Linda Plzeň 2012 Tato stránka bude ve svázané práci Váš původní formulář Zadáni bak. práce (k vyzvednutí u sekretářky KAN) Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracoval/a samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a zdrojů informací. V Plzni dne 19. června 2012 ……………………………. Jiří Linda ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank to my supervisor Brad Vice, Ph.D., for his help, opinions and suggestions. My thanks also belong to my loved ones for their support and patience. ABSTRACT Linda, Jiří. University of West Bohemia. May, 2012. The Rise of the American Comic into the Role of Serious Art. Supervisor: Brad Vice, Ph.D. The object of this undergraduate thesis is to map the development of sequential art, comics, in the form of respectable art form influencing contemporary other artistic areas. Modern comics were developed between the World Wars primarily in the United States of America and therefore became a typical part of American culture. The thesis is divided into three major parts. The first part called Sequential Art as a Medium discusses in brief the history of sequential art, which dates back to ancient world. The chapter continues with two sections analyzing the comic medium from the theoretical point of view. The second part inquires the origin of the comic book industry, its cultural environment, and consequently the birth of modern comic book. -

Comic Books: Superheroes/Heroines, Domestic Scenes, and Animal Images

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1980 Volume II: Art, Artifacts, and Material Culture Comic Books: Superheroes/heroines, Domestic Scenes, and Animal Images Curriculum Unit 80.02.03 by Patricia Flynn The idea of developing a unit on the American Comic Book grew from the interests and suggestions of middle school students in their art classes. There is a need on the middle school level for an Art History Curriculum that will appeal to young people, and at the same time introduce them to an enduring art form. The history of the American Comic Book seems appropriately qualified to satisfy that need. Art History involves the pursuit of an understanding of man in his time through the study of visual materials. It would seem reasonable to assume that the popular comic book must contain many sources that reflect the values and concerns of the culture that has supported its development and continued growth in America since its introduction in 1934 with the publication of Famous Funnies , a group of reprinted newspaper comic strips. From my informal discussions with middle school students, three distinctive styles of comic books emerged as possible themes; the superhero and the superheroine, domestic scenes, and animal images. These themes historically repeat themselves in endless variations. The superhero/heroine in the comic book can trace its ancestry back to Greek, Roman and Nordic mythology. Ancient mythologies may be considered as a way of explaining the forces of nature to man. Examples of myths may be found world-wide that describe how the universe began, how men, animals and all living things originated, along with the world’s inanimate natural forces. -

The Media Assemblage: the Twentieth-Century Novel in Dialogue with Film, Television, and New Media

THE MEDIA ASSEMBLAGE: THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY NOVEL IN DIALOGUE WITH FILM, TELEVISION, AND NEW MEDIA BY PAUL STEWART HACKMAN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Robert Markley Associate Professor Jim Hansen Associate Professor Ramona Curry ABSTRACT At several moments during the twentieth-century, novelists have been made acutely aware of the novel as a medium due to declarations of the death of the novel. Novelists, at these moments, have found it necessary to define what differentiates the novel from other media and what makes the novel a viable form of art and communication in the age of images. At the same time, writers have expanded the novel form by borrowing conventions from these newer media. I describe this process of differentiation and interaction between the novel and other media as a “media assemblage” and argue that our understanding of the development of the novel in the twentieth century is incomplete if we isolate literature from the other media forms that compete with and influence it. The concept of an assemblage describes a historical situation in which two or more autonomous fields interact and influence one another. On the one hand, an assemblage is composed of physical objects such as TV sets, film cameras, personal computers, and publishing companies, while, on the other hand, it contains enunciations about those objects such as claims about the artistic merit of television, beliefs about the typical audience of a Hollywood blockbuster, or academic discussions about canonicity. -

Narrative Time and Mental Space in the Graduate, Catch-22, and Carnal Knowledge

Montclair State University Montclair State University Digital Commons Theses, Dissertations and Culminating Projects 8-2020 Architecture of the Mind : Narrative Time and Mental Space in The Graduate, Catch-22, and Carnal Knowledge Monica Cecilia Winston Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons ABSTRACT This thesis explores three of director Mike Nichols’s films produced during the New Hollywood period—The Graduate (1967), Catch-22 (1970), and Carnal Knowledge (1971)—in an effort to trace Nichols’s auteur signature as it relates to the depiction of the protagonist’s subjectivity and renders post-war male anxiety and existential dread. In addition to discussing formal film technique used to depict the mental space of the protagonist, how these subjective sequences are implemented in the film bears implications on the narrative form and situates Nichols alongside other New Hollywood directors who were influenced by art cinema. This analysis, like those posited by other critics influenced by film theorist David Bordwell, distinguishes the term “art cinema” as employing a range of techniques outside of continuity editing that are read as stylistic, and because of this it entails specific modes of viewership in order to find meaning in style. Because of the function of style, the thesis posits thematic kinship among The Graduate, Catch-22, and Carnal Knowledge, which enriches the film’s respective meanings when viewed side by side. MONTCLAIR STATE UNIVERSITY Architecture of the Mind: Narrative Time and Mental Space in The Graduate, Catch-22, and Carnal Knowledge by Monica Cecilia Winston A Master’s Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Montclair State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts August 2020 College: College of Humanities and Social Sciences Department: English Dr.