A Synthesis of the 2001-2004 Peace Native Grasslands Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Methods and Work Profile

REVIEW OF THE KNOWN AND POTENTIAL BIODIVERSITY IMPACTS OF PHYTOPHTHORA AND THE LIKELY IMPACT ON ECOSYSTEM SERVICES JANUARY 2011 Simon Conyers Kate Somerwill Carmel Ramwell John Hughes Ruth Laybourn Naomi Jones Food and Environment Research Agency Sand Hutton, York, YO41 1LZ 2 CONTENTS Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 8 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 13 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 Objectives .......................................................................................................................... 15 2. Review of the potential impacts on species of higher trophic groups .................... 16 2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 16 2.2 Methods ............................................................................................................................. 16 2.3 Results ............................................................................................................................... 17 2.4 Discussion .......................................................................................................................... 44 3. Review of the potential impacts on ecosystem services ....................................... -

Survey of the Lepidoptera Fauna in Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park

Survey of the Lepidoptera Fauna in Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park Platarctia parthenos Photo: D. Vujnovic Prepared for: Alberta Natural Heritage Information Centre, Parks and Protected Areas Division, Alberta Community Development Prepared by: Doug Macaulay and Greg Pohl Alberta Lepidopterists' Guild May 10, 2005 Figure 1. Doug Macaulay and Gerald Hilchie walking on a cutline near site 26. (Photo by Stacy Macaulay) Figure 2. Stacey Macaulay crossing a beaver dam at site 33. (Photo by Doug Macaulay) I TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................... 1 METHODS .............................................................................................................................. 1 RESULTS ................................................................................................................................ 3 DISCUSSION .......................................................................................................................... 4 I. Factors affecting the Survey...........................................................................................4 II. Taxa of particular interest.............................................................................................5 A. Butterflies:...................................................................................................................... 5 B. Macro-moths .................................................................................................................. -

Regular Council Meeting June 24, 2020 10:00 Am Fort Vermilion Council Chambers

MACKENZIE COUNTY REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING JUNE 24, 2020 10:00 AM FORT VERMILION COUNCIL CHAMBERS 780.927.3718 www.mackenziecounty.com 4511-46 Avenue, Fort Vermilion [email protected] MACKENZIE COUNTY REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING Wednesday, June 24, 2020 10:00 a.m. Fort Vermilion Council Chambers Fort Vermilion, Alberta AGENDA Page CALL TO ORDER: 1. a) Call to Order AGENDA: 2. a) Adoption of Agenda ADOPTION OF 3. a) Minutes of the June 10, 2020 Regular Council 7 PREVIOUS MINUTES: Meeting b) Minutes of the June 15, 2020 Special Council 19 Meeting c) Business Arising out of the Minutes DELEGATIONS: 4. a) b) TENDERS: Tender openings are scheduled for 11:00 a.m. 5. a) 1998 Water Truck 25 PUBLIC HEARINGS: Public hearings are scheduled for 1:00 p.m. 6. a) Bylaw 1181-20 Land Use Bylaw Amendment to 27 Rezone Plan 2938RS, Block 02, Lots 15 & 16 from Fort Vermilion Commercial Centre “FV-CC” to Hamlet Residential 1 “HR-1” (Fort Vermilion) GENERAL 7. a) Disaster Recovery Update (verbal report) REPORTS: b) AGRICULTURE 8. a) 2020 Capital Budget Amendment – Agronomy 37 SERVICES: Building b) MACKENZIE COUNTY PAGE 2 REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA Wednesday, June 24, 2020 COMMUNITY 9. a) Wadlin Lake Management Plan – 10-Year Plan 41 SERVICES: b) Search and Rescue River Access Plan 89 c) Request to Waive a Fire Invoice – Abraham 107 Friessen d) LA on Wheels Society – Request to Amend the 109 Handi-Bus Agreement e) FINANCE: 10. a) Expense Claims – Councillors 129 b) Expense Claims – Members at Large 131 c) Utility Invoices June & July, 2020 – Flood 133 Affected Areas d) OPERATIONS: 11. -

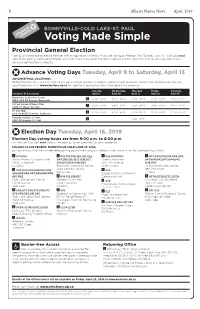

Voting Made Simple

8 Alberta Native News April, 2019 BONNYVILLE-COLD LAKE-ST. PAUL Voting Made Simple Provincial General Election Voting will take place to elect a Member of the Legislative Assembly. If you are voting on Election Day, Tuesday, April 16, 2019, you must vote at the polling station identified for you in the map. If you prefer to vote in advance, from April 9 to April 13, you may vote at any advance poll location in Alberta. Advance Voting Days Tuesday, April 9 to Saturday, April 13 ADVANCE POLL LOCATIONS Before Election Day, you may vote at any advance poll location in Alberta. Advance poll locations nearest your electoral division are specified below. Visit www.elections.ab.ca for additional polling locations throughout the province. Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Advance Poll Location April 9 April 10 April 11 April 12 April 13 Bonnyville Centennial Centre 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 1003, 4313 50 Avenue, Bonnyville St.Paul Senior Citizens Club 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 4809 47 Street, St. Paul Tri City Mall 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM Unit 20, 6503 51 Street, Cold Lake Portage College St. Paul 9 AM - 8 PM 5205 50 Avenue, St. Paul Election Day Tuesday, April 16, 2019 Election Day voting hours are from 9:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. -

Report on the Badlands/Parkland Lepidoptera Survey 2017 by the Alberta Lepidopterists' Guild, Under Research Permit #17-171

Report on the Badlands/Parkland Lepidoptera Survey 2017 by the Alberta Lepidopterists' Guild, under research permit #17-171 Report to Alberta Tourism, Park and Recreation, Parks Division November 2017 by Gregory R. Pohl Gregory Pohl and other members of the Alberta Lepidopterists' Guild were granted a research permit (#17-171) for moth and butterfly (Lepidoptera) observation and collection in the Tolman - Rumsey area of central Alberta in the summer of 2017. This is our report of the species observed and collected in the area. Study Sites: The following sites were visited and sampled for Lepidoptera: 1. Rowley townsite (Figure 1). 51.760°N 112.786°W. July 14-16, 2017. Abandoned home sites and field margins; disturbed area along train tracks. Although not a protected area requiring a permit, this was our base of operations and camping area, it was convenient to observe and collect moths and butterflies here. Most of the species encountered here are expected to occur in nearby parks and natural areas. Collecting methods - daytime observation and netting; UV light traps; mercury vapour lights. 2. "North Rumsey": Township Road 589, vicinity of Rumsey Natural Area. 51.965°N 112.625°W. July 15, 2017. Rolling parkland with small sloughs. Although not technically within the Rumsey Natural Area, this site is very near and is comprised of similar habitat. The species seen here are all expected within the natural area. Collecting methods - daytime observation and netting. 3. "West Rumsey": Western edge of Rumsey Natural Area (Figure 2). 51.882°N 112.691°W. July 15, 2017. Rolling parkland and grassland. -

Survey of Lepidoptera of the Wainwright Dunes Ecological Reserve

SURVEY OF LEPIDOPTERA OF THE WAINWRIGHT DUNES ECOLOGICAL RESERVE Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 159 SURVEY OF LEPIDOPTERA OF THE WAINWRIGHT DUNES ECOLOGICAL RESERVE Doug Macaulay Alberta Species at Risk Report No.159 Project Partners: i ISBN 978-1-4601-3449-8 ISSN 1496-7146 Photo: Doug Macaulay of Pale Yellow Dune Moth ( Copablepharon grandis ) For copies of this report, visit our website at: http://www.aep.gov.ab.ca/fw/speciesatrisk/index.html This publication may be cited as: Macaulay, A. D. 2016. Survey of Lepidoptera of the Wainwright Dunes Ecological Reserve. Alberta Species at Risk Report No.159. Alberta Environment and Parks, Edmonton, AB. 31 pp. ii DISCLAIMER The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies of the Department or the Alberta Government. iii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... vi 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 STUDY AREA ............................................................................................................. 2 3.0 METHODS ................................................................................................................... 6 4.0 RESULTS .................................................................................................................... -

List of Insect Species Which May Be Tallgrass Prairie Specialists

Conservation Biology Research Grants Program Division of Ecological Services © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources List of Insect Species which May Be Tallgrass Prairie Specialists Final Report to the USFWS Cooperating Agencies July 1, 1996 Catherine Reed Entomology Department 219 Hodson Hall University of Minnesota St. Paul MN 55108 phone 612-624-3423 e-mail [email protected] This study was funded in part by a grant from the USFWS and Cooperating Agencies. Table of Contents Summary.................................................................................................. 2 Introduction...............................................................................................2 Methods.....................................................................................................3 Results.....................................................................................................4 Discussion and Evaluation................................................................................................26 Recommendations....................................................................................29 References..............................................................................................33 Summary Approximately 728 insect and allied species and subspecies were considered to be possible prairie specialists based on any of the following criteria: defined as prairie specialists by authorities; required prairie plant species or genera as their adult or larval food; were obligate predators, parasites -

Zoogeography of the Holarctic Species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): Importance of the Bering Ian Refuge

© Entomologica Fennica. 8.XI.l991 Zoogeography of the Holarctic species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): importance of the Bering ian refuge Kauri Mikkola, J, D. Lafontaine & V. S. Kononenko Mikkola, K., Lafontaine, J.D. & Kononenko, V. S. 1991 : Zoogeography of the Holarctic species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): importance of the Beringian refuge. - En to mol. Fennica 2: 157- 173. As a result of published and unpublished revisionary work, literature compi lation and expeditions to the Beringian area, 98 species of the Noctuidae are listed as Holarctic and grouped according to their taxonomic and distributional history. Of the 44 species considered to be "naturall y" Holarctic before this study, 27 (61 %) are confirmed as Holarctic; 16 species are added on account of range extensions and 29 because of changes in their taxonomic status; 17 taxa are deleted from the Holarctic list. This brings the total of the group to 72 species. Thirteen species are considered to be introduced by man from Europe, a further eight to have been transported by man in the subtropical areas, and five migrant species, three of them of Neotropical origin, may have been assisted by man. The m~jority of the "naturally" Holarctic species are associated with tundra habitats. The species of dry tundra are frequently endemic to Beringia. In the taiga zone, most Holarctic connections consist of Palaearctic/ Nearctic species pairs. The proportion ofHolarctic species decreases from 100 % in the High Arctic to between 40 and 75 % in Beringia and the northern taiga zone, and from between 10 and 20 % in Newfoundland and Finland to between 2 and 4 % in southern Ontario, Central Europe, Spain and Primorye. -

MARA 2016 Research Report

MACKENZIE APPLIED RESEARCH ASSOCIATION [MARA] 2016 RESEARCH REPORT CONTACT P. O. Box 646, Fort Vermilion Alberta, Canada T0H1N0 Phone: 780-927-3776 www.mackenzieresearch.ca Mission and Purpose of MARA MARA is a not for profit, producer managed and driven applied research association that conducts agriculture and environmental research from its base in Fort Vermilion, Alberta. The central aims of MARA are to conduct relevant crop and livestock research and demonstration trials, develop fertilization strategies and innovative means to manage soils and lands to enhance production while protecting the environment. Extension work to deliver new and improved management practices, dissemination of research data and emerging information are at the heart of our mission. MARA recognizes the unique climate, soils and seasonality of this region and our role to provide producers with best management practices based on sound, verified science applied to this region. Our ultimate goal is to help producers increase production at reduced cost in environmentally sustainable manner. Permissions to use Data and Reports from MARA MARA exists to create new scientific data for use by the agricultural community in northern Alberta. Permission is granted to all members of MARA to use data contained in all MARA reports and publications to improve management of their lands and increase return on investment. However, if any data are used for publications, academic purposes or in agency publications, permission should be sought in writing from MARA and appropriate credit given to MARA before the data can be used. Trial work performed for private businesses and results of all of those studies are the property of those businesses. -

Large Scale WAN Emulation

Large Scale WAN Emulation Martin Arlitt Rob Simmonds Carey Williamson - University of Calgary Calgary Alberta March 18, 2002 Outline • Overview of WAN Simulation & Emulation • Introduction to IP-TNE • Discussion of Related Projects • Validation of IP-TNE • Current Projects Involving IP-TNE • Future Work 1 Performance Evaluation Approaches 1. Experimental + offers the most realistic environment - requires significant financial investment - can be difficult to repeat results - restricted to existing technologies 2 Performance Evaluation Approaches 2. Simulation + low-cost, flexible, controllable, reproducible environment - abstractions can compromise usefulness of results 3. Analytical + provides quick answers - often requires the greatest degrees of abstraction 3 Performance Evaluation Approaches 4. Emulation * a hybrid performance evaluation methodology * combines aspects of other three approaches + enables controlled experimentation with existing applications - still suffers from drawbacks of other approaches 4 Wide-Area Network Simulation • provides a virtual Wide-Area Network (WAN) environment • allows all network conditions to be controlled – packet loss – packet reordering/duplication – link bandwidths – propogation delays – asymetric links – bounded queue sizes – multipath • allows alternative networking technologies to be evaluated 5 Wide-Area Network Emulation • extends capabilities of WAN simulation • enables controlled testing with unmodified applications • both simulation and emulation are important tools 6 Challenges • scaling to large, -

Check List of Noctuid Moths (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae And

Бiологiчний вiсник МДПУ імені Богдана Хмельницького 6 (2), стор. 87–97, 2016 Biological Bulletin of Bogdan Chmelnitskiy Melitopol State Pedagogical University, 6 (2), pp. 87–97, 2016 ARTICLE UDC 595.786 CHECK LIST OF NOCTUID MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA: NOCTUIDAE AND EREBIDAE EXCLUDING LYMANTRIINAE AND ARCTIINAE) FROM THE SAUR MOUNTAINS (EAST KAZAKHSTAN AND NORTH-EAST CHINA) A.V. Volynkin1, 2, S.V. Titov3, M. Černila4 1 Altai State University, South Siberian Botanical Garden, Lenina pr. 61, Barnaul, 656049, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Tomsk State University, Laboratory of Biodiversity and Ecology, Lenina pr. 36, 634050, Tomsk, Russia 3 The Research Centre for Environmental ‘Monitoring’, S. Toraighyrov Pavlodar State University, Lomova str. 64, KZ-140008, Pavlodar, Kazakhstan. E-mail: [email protected] 4 The Slovenian Museum of Natural History, Prešernova 20, SI-1001, Ljubljana, Slovenia. E-mail: [email protected] The paper contains data on the fauna of the Lepidoptera families Erebidae (excluding subfamilies Lymantriinae and Arctiinae) and Noctuidae of the Saur Mountains (East Kazakhstan). The check list includes 216 species. The map of collecting localities is presented. Key words: Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Erebidae, Asia, Kazakhstan, Saur, fauna. INTRODUCTION The fauna of noctuoid moths (the families Erebidae and Noctuidae) of Kazakhstan is still poorly studied. Only the fauna of West Kazakhstan has been studied satisfactorily (Gorbunov 2011). On the faunas of other parts of the country, only fragmentary data are published (Lederer, 1853; 1855; Aibasov & Zhdanko 1982; Hacker & Peks 1990; Lehmann et al. 1998; Benedek & Bálint 2009; 2013; Korb 2013). In contrast to the West Kazakhstan, the fauna of noctuid moths of East Kazakhstan was studied inadequately. -

Pukaskwa Taxonomy Report

Pukaskwa Taxonomy Report Class Order Family Species Arachnida Araneae Agelenidae Agelenopsis utahana Amaurobiidae Callobius bennetti Cybaeopsis euopla Araneidae Hypsosinga rubens Clubionidae Clubiona canadensis Dictynidae Emblyna annulipes Emblyna phylax Linyphiidae Bathyphantes canadensis Ceraticelus atriceps Ceraticelus fissiceps Ceraticelus laetabilis Ceratinopsis nigriceps Dismodicus decemoculatus Drapetisca alteranda Grammonota angusta Lophomma depressum Phlattothrata flagellata Pityohyphantes subarcticus Pocadicnemis americana Sciastes truncatus Scyletria inflata Souessa spinifera Tapinocyba simplex Tapinocyba sp. 1GAB Lycosidae Pardosa hyperborea Pardosa moesta Pardosa xerampelina Philodromidae Philodromus peninsulanus Philodromus rufus vibrans Theridiidae Canalidion montanum Dipoena sp. 1GAB Theridion differens Theridion pictum Thomisidae Xysticus emertoni Xysticus montanensis Mesostigmata Blattisociidae Digamasellidae Dinychidae Laelapidae Parasitidae Phytoseiidae Trematuridae Trichouropoda moseri Pseudoscorpiones Chernetidae Sarcoptiformes Alycidae Ceratozetidae Oribatulidae Scheloribatidae 1 Tegoribatidae Trhypochthoniidae Trhypochthonius cladonicolus Trombidiformes Anisitsiellidae Anystidae Bdellidae Cunaxidae Erythraeidae Eupodidae Hydryphantidae Lebertiidae Limnesiidae Microdispidae Rhagidiidae Scutacaridae Siteroptidae Tetranychidae Trombidiidae Collembola Entomobryomorpha Entomobryidae Entomobrya comparata Entomobrya nivalis Isotomidae Tomoceridae Poduromorpha Brachystomellidae Symphypleona Bourletiellidae Katiannidae