The State of Sustainability in Japan 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Agency Family Tree

2017 GLOBAL AGENCY FAMILY TREE TOP 10 WPP OMNICOM Publicis Groupe INTERPUBLIC Dentsu HAVAS HAKUHODO DY MDC Partners CHEIL BlueFocus (Revenue US 17,067M) (Revenue US 15,417M) (Revenue US 10,252M) (Revenue US 7,847M) (Revenue US 7,126M) (Revenue US 2,536M) (Revenue US 2,282M) (Revenue US 1,370M) (Revenue US 874M) (Revenue US 827M) OGILVY GROUP WPP DIGITAL BBDO WORLDWIDE PUBLICIS COMMUNICATIONS MEDIABRANDS DENTSU INC. DENTSU AEGIS NETWORK HAVAS CREATIVE GROUP HAKUHODO HAKUHODO MDC PARTNERS CHEIL WORLDWIDE DIGITAL Ogilvy & Mather ACCELERATION BBDO Worldwide Publicis Worldwide Ansible Dentsu Inc. Other Agencies Havas Worldwide Hakuhodo Hakuhodo 6degrees Cheil Worldwide BlueDigital OgilvyOne Worldwide BLUE STATE DIGITAL Proximity Worldwide Publicis BPN DENTSU AEGIS NETWORK Columbus Arnold Worldwide ADSTAFF-HAKUHODO Delphys Hakuhodo International 72andSunny Barbarian Group Phluency Ogilvy CommonHealth Worldwide Cognifide Interone Publicis 133 Cadreon Dentsu Branded Agencies Copernicus Havas Health Ashton Consulting Hakuhodo Consulting Asia Pacific Sundae Beattie McGuinness Bungay Madhouse Ogilvy Government Relations F.BIZ Organic Publicis Activ Identity Dentsu Coxinall BETC Backs Group Grebstad Hicks Communications Allison + Partners McKinney Domob Ogilvy Public Relations HOGARTH WORLDWIDE Wednesday Agency Publicis Africa Group Initiative DentsuBos Inc. Crimson Room FullSIX Brains Work Associates Taiwan Hakuhodo Anomaly Cheil Pengtai Blueplus H&O POSSIBLE DDB WORLDWIDE Publicis Conseil IPG Media LAB Dentsu-Smart LLC deepblue HAVAS MEDIA GROUP -

Acronym Media

Booth #18 Acronym Media 350 Fifth Avenue, Suite 6520, New York, NY 10118 (212) 691-7051 What We Do Acronym has been providing world-class keyword-driven marketing services for blue-chip clients since 1995. Privately funded and founded by Anton Konikoff, Acronym employs 85 full-time Search Marketing experts worldwide. From our headquarters in the iconic Empire State Building in New York City, Acronym manages campaigns in over 70 countries and dozens of languages. We have offices in Raleigh, N.C., Singapore and various other locations that help us to execute global search campaigns. Our client roster consists of mid-size organizations in localized regions to large enterprise brands in nearly all verticals, from travel and healthcare to business technology and retail. We specialize in Organic SEO, Paid Search, Social Media, Affiliate Marketing, Usability Consulting and Deep-Dive Analytics. Specialties SEO, SEM, Search Engine Optimization, Search Engine Marketing, PPC, Online Marketing, Social Media, Affiliate Marketing, Analytics, Keyword-driven Marketing, Marketing, Web Marketing, Digital Marketing. Positions Available Internships: Please inquire at the Acronym Media booth about internships. Full-Time: - Paid Search (PPC) - Search Engine Optimization (SEO) - Web Analytics 1 Booth #46 Behrman Communications 270 Madison Avenue, Suite 402, New York, NY 10016 What We Do Behrman Communications is a full-service public relations agency in Midtown Manhattan with an expertise in the beauty, health, accessories and lifestyle sectors. We specialize in a manifold of strategies including thematic special events, cross promotions / strategic partnerships, in- store promotions, social media programming, material development, and national & regional print, online and broadcast initiatives. We are seeking dynamic and energetic interns to join our internship program for college credit. -

Interpublic Group of Companies, Inc. (The) Annual Report 2019

Interpublic Group of Companies, Inc. (The) Annual Report 2019 Form 10-K (NYSE:IPG) Published: February 25th, 2019 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K ý ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018 or o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 1-6686 THE INTERPUBLIC GROUP OF COMPANIES, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 13-1024020 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 909 Third Avenue, New York, New York 10022 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (212) 704-1200 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $0.10 par value New York Stock Exchange Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ý No ¨ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No ý Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

2016 Annual Report

2016 ƂiÌÌiÀvÀ"ÕÀ >À> 2016 HIGHLIGHTS To our shareholders: Across the board, 2016 was a very successful year for our company. We Grew revenues to $7.85 billion «ÃÌi`ÃÌÀ}w>V>ÀiÃÕÌÃ]>}>i`ÕÀ}L>«iiÀ}ÀÕ«À}>V ÀiÛiÕi}ÀÜÌ ]>`}>ÀiÀi`Ì i } iÃÌiÛivÀiV}ÌvÀÌ i VÀi>ÌÛÌÞ>`ivviVÌÛiiÃÃvÕÀÜÀÛiÀ>`iV>`i°"ÕÀ`}Ì>vviÀ}à Delivered industry-leading organic VÌÕi`ÌLi>Ã}wV>Ì`ÀÛiÀv}ÀÜÌ ]>`ÜiVÌÕi`ÌLÕ` revenue growth of 5% ÕÀÕÌÃÌ>`}`}Ì>iÝ«iÀÌÃi>VÀÃÃÌ i«ÀÌv°/ iÃiV>«>LÌiÃ] VLi`ÜÌ ÕÀÃÌÀi}Ì `iÛiÀ}Ìi}À>Ìi`ÃÕÌÃ]«ÃÌÕà Further expanded operating margin ÜiÌÃiÀÛi>Ã>ÛÌ>«>ÀÌiÀ i«}ÕÀViÌÃ>Û}>ÌiÌ`>Þ½ÃV«iÝ by 50 basis points to 12% >ÀiÌ}i`>iÛÀiÌ° Óä£ÈÜi>``Ì>Þ`iÃÌÀ>Ìi`ÕÀVÌÕi`>LÌÞÌvVÕà Adjusted diluted EPS1 rose 13% >``iÛiÀ«ÀÛiiÌëÀwÌ>LÌÞÌ >Ì>Ãi`Ì i`ÕÃÌÀÞ°7i>Ài Vw`iÌÌ >Ì>À}iÝ«>Ã>`V>«Ì>ÀiÌÕÀÃÜÀi>«ÜiÀvÕ `ÀÛiÀÃvÛ>ÕivÀÌiÀ«ÕLV}}vÀÜ>À`°/ iÃi>ÀiÌ iv>VÌÀÃÌ >Ì Returned an additional $542 million vÕii`w>V>«iÀvÀ>ViÌ >ÌiÝVii`i`Ì iÌ>À}iÌÃÜi >`ÃiÌ>ÌÌ i to shareholders through share outset of 2016. repurchases and dividends, bringing capital returns to our owners to 2016 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS $3 billion since 2011 "À}>VÀiÛiÕi}ÀÜÌ Ü>Ãx°ä¯vÀÌ ivÕÞi>À>`> i>`vÕÀvÕ Þi>ÀÌ>À}iÌ°7i}ÀiÜÀ}>V>ÞiÛiÀÞ>ÀÀi}vÌ iÜÀ`]>` >VÀÃÃi>ÀÞ>>À>}iViÃ>`ViÌÃiVÌÀð/ ÃÀiÃÕÌ>Ài`Ì i Raised dividends by 20% for 2017, Ì À`VÃiVÕÌÛiÞi>ÀÜ V ÜiÕÌ«iÀvÀi`Ì i`ÕÃÌÀÞÌ ÃiÞ >À}ÕÀwvÌ VÃiVÕÌÛiÞi>Àv «iÀvÀ>ViiÌÀV° dividend increases of at least 20% "«iÀ>Ì}>À}Ü>ãӰä¯]>VÀi>ÃivxäL>ÃëÌÃvÀÓä£x] >V iÛ}Ì i>À}Ì>À}iÌÃiÌLÞ>>}iiÌ>ÌÌ iLi}}vÌ iÞi>À° 7Ì ÓÇäL>ÃëÌÃv>À}«ÀÛiiÌÛiÀÌ i«>ÃÌÌ ÀiiÞi>ÀÃ]Üi >ÀiÃ`ÞÌÀ>VÌÜ>À`>V iÛ}ÕÀ}ÃÌ>`}LiVÌÛivvÕÞ £-iivÕÀiVV>ÌÃv>`ÕÃÌi``ÕÌi`i>À}ëiÀ -

Meet UK Advertising Brochure 2020

MEET UK ADVERTISING WITH ITS POOL OF DIVERSE SKILLS, GLOBAL TALENT AND UNPRECEDENTED CREATIVE CAPABILITIES, THE UK ADVERTISING MARKET IS NOT JUST YOUR GATEWAY TO BRITAIN; IT’S YOUR GATEWAY TO EVERYWHERE. The UK has a long heritage as one of the world’s leading hubs for advertising and marketing services, and as we adapt to the impact of Covid-19, UK advertising is very much open for business and continues to work with clients and partners all around the world. Much of our work is driven by our position as the world’s most advanced digital advertising economy, third only in size to the US and China, according to a recent report by Credos, UK advertising’s thinktank. We are the best in the world because we have the best people in the world working in our industry and we want to keep it that way. That’s reflected in our performance year-after-year at Cannes Lions. Over the past 15 years, UK Advertising has won more Lions than any other European country and more per capita than any other country in the world. All of this means we can provide international businesses with an unrivalled concentration of expertise, creativity and knowhow, to produce the world’s most effective advertising work. UKAEG is delighted to showcase UK Advertising companies who currently do business with countries all over the world, from USA to China, from Australia to the UAE as well as across our fellow nations in Europe, leading with Germany, France, Netherlands, Italy and Spain. To find out more about UK Advertising or where to meet us visit our hub https://www.adassoc.org.uk/ukadvertising/ THE UKAEG COMMUNITY 23red is a purpose-driven creative agency that develop brands and campaigns that change behaviour for the better and have a positive impact on people’s lives. -

Report 2017 IPG GRI Report

Global Reporting Initiative Index 2017 General Strategy & Organizational Identified Standard Analysis Profile Material Disclosures Aspects & Boundaries Stakeholder Report Profile Governance Ethics & Engagement Integrity Specific Economic Labor Practices Environment Standard & Decent Work Disclosures 1 Click here to access information about UN Global Compact Communication on Progress Human Rights Society 2 Global Reporting Initiative Index Interpublic is committed to operating sustainably. To us, this means measuring our carbon footprint and working toward limiting that footprint; respecting and encouraging diversity; and being a good corporate citizen of the communities where our employees live and work. 3 General Standard Disclosures: Strategy & Analysis GRI Reporti Indicato G4-1 ng Level r Sustainability – conducting our business ethically, and in line with the long-term health of the communities where our employees live and work – is key to IPG’s business strategy, and to the ethical operation of our company. During the past year, we have taken steps to strengthen our commitment to operating sustainably. In this, our third year of reporting on our sustainability initiatives utilizing the GRI-G4 framework, we have continued to strengthen our commitment to operating sustainably. This year, we expanded the measurement of our emissions and other environmental impacts using GHG Protocol Corporate Standards. We expanded our boundary from last year to include three of our largest offices around Paris, France. Further, we expanded our boundary in North America by including all offices which are over 50,000 square feet (down from 100,000 square feet last year) and in the UK, this year, we included 40% of our portfolio and 100% of our owned facilities. -

IPG Agencies Create Customized Marketing Programs for Many of the World's Largest Companies Through Our Comprehensive Global Services

Global Reporting Initiative Index 2018 Universal Organizational Strategy Ethics & Standards Profile Integrity Governance Stakeholder Reporting Management Engagement Practice Approach Topic- ECONOMIC: ECONOMIC: ECONOMIC: Specific Economic Indirect Anti-Corruption Standards Performance Economic Impacts 1 ENVIRONMENT ENVIRONMENT ENVIRONMENT SOCIAL: AL: Energy AL: Emissions AL: Supplier Employment Environmental Assessment SOCIAL: SOCIAL: SOCIAL: Human SOCIAL: Training and Diversity and Rights Supplier Social Education Equal Assessment Assessment Opportunity Click here to access information about UN Global Compact Communication on Progress SOCIAL: Public Policy 2 Global Reporting Initiative Index Interpublic is committed to operating sustainably. To us, this means measuring our carbon footprint and working toward limiting that footprint; respecting and encouraging diversity; and being a good corporate citizen of the communities where our employees live and work. 3 Universal Standards: Organizational Profile GRI Reporti Indicato 102-2 ng Level r Disclosure 102-2 Report the primary activities, brands, products and services Interpublic group is a global provider of marketing solutions. Through our 50,200 employees in all major world markets, our companies specialize in consumer advertising, digital marketing, communications planning and media buying, public relations and specialty marketing. IPG agencies create customized marketing programs for many of the world's largest companies through our comprehensive global services. The work our agencies produce helps clients build brands, increase sales of their products and services and gain market share. The work we provide clients is specific to their unique needs. Our solutions vary from project- based activity involving one agency to long-term, fully integrated campaigns created by multiple IPG agencies working together. With offices in over 100 countries, we can operate in a single region, or deliver globally integrated programs. -

2016 IPG Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

Global Reporting Initiative Index 2016 General Strategy & Organizational Identified Standard Analysis Profile Material Disclosures Aspects & Boundaries Stakeholder Report Profile Governance Ethics & Engagement Integrity Specific Economic Labor Practices Environment Standard & Decent Work Disclosures 1 Click here to access information about UN Global Compact Communication on Progress Human Rights Society 2 Global Reporting Initiative Index Interpublic is committed to operating sustainably. To us, this means measuring our carbon footprint and working toward limiting that footprint, respecting and encouraging diversity, and being a good corporate citizen of the communities where our employees live and work. 3 General Standard Disclosures: Strategy & Analysis GRI Reporti Indicato G4-1 ng Level r Understanding that sustainability is a significant opportunity as well as an important responsibility for our company, we began, a year ago, to report on our sustainability initiatives utilizing the GRI-G4 framework. In this, our second year of reporting, we continue to progress on our sustainability journey, making strides on this key indicator of our success as a company and as a corporate citizen. This year, we have expanded the measurement of our greenhouse gas emissions to include not only our largest buildings in the United States, but also nearly all of our properties in the UK. Our plan is to continue to expand this boundary to get a fuller picture of our impact as well as to set targets for reduction going forward. We have also continued our support of the UN Global Compact. As a UN Global Compact signatory, we have publically committed to the 10 principles that the compact embraces in the areas of environmental sustainability, fair labor practices, human rights and anti-corruption. -

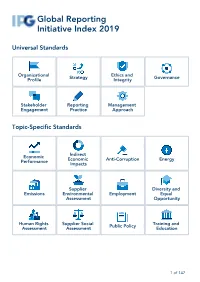

2019 IPG Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

Global Reporting Initiative Index 2019 Universal Standards Organizational Ethics and Strategy Governance Profile Integrity Stakeholder Reporting Management Engagement Practice Approach Topic-Specific Standards Indirect Economic Economic Anti-Corruption Energy Performance Impacts Supplier Diversity and Emissions Environmental Employment Equal Assessment Opportunity Human Rights Supplier Social Training and Public Policy Assessment Assessment Education 1 of 153 Global Reporting Initiative Index 2019 Interpublic is committed to operating sustainably. To us, this means measuring our carbon footprint and working toward limiting that footprint; respecting and encouraging diversity; and being a good corporate citizen of the communities where our employees live and work. 2 of 153 Organizational Profile Universal Standards GRI Indicator Reporting Level 102-1 Complete Report the name of the organization Interpublic Group of Companies, Inc. 102-1 Report the Name of the Organization Interpublic Group of Companies, Inc. 3 of 153 Organizational Profile Universal Standards GRI Indicator Reporting Level 102-2 Complete Report the primary activities, brands, products and services IPG operates in all major world markets – our companies specialize in consumer advertising, digital marketing, communications planning and media buying, public relations and specialized communications disciplines. We are one of the world’s premier global advertising and marketing services companies. Through our 54,000 employees in all major world markets, our companies specialize in consumer advertising, digital marketing, communications planning and media buying, public relations and specialized communications disciplines. Our agencies create customized marketing programs for clients that range in scale from large global marketers to regional and local clients. Comprehensive global services are critical to effectively serve our multinational and local clients in markets throughout the world as they seek to build brands, increase sales of their products and services, and gain market share. -

Global Reporting Initiative Index 2019

Global Reporting Initiative Index 2019 Universal Standards Organizational Ethics and Strategy Governance Profile Integrity Stakeholder Reporting Management Engagement Practice Approach Topic-Specific Standards Indirect Economic Economic Anti-Corruption Energy Performance Impacts Supplier Diversity and Emissions Environmental Employment Equal Assessment Opportunity Human Rights Supplier Social Training and Public Policy Assessment Assessment Education 1 of 147 Global Reporting Initiative Index 2019 Interpublic is committed to operating sustainably. To us, this means measuring our carbon footprint and working toward limiting that footprint; respecting and encouraging diversity; and being a good corporate citizen of the communities where our employees live and work. 2 of 147 Organizational Profile Universal Standards GRI Indicator Reporting Level 102-1 Complete Report the name of the organization Interpublic Group of Companies, Inc. 102-1 Report the Name of the Organization Interpublic Group of Companies, Inc. 3 of 147 Organizational Profile Universal Standards GRI Indicator Reporting Level 102-2 Complete Report the primary activities, brands, products and services IPG operates in all major world markets – our companies specialize in consumer advertising, digital marketing, communications planning and media buying, public relations and specialized communications disciplines. We are one of the world’s premier global advertising and marketing services companies. Through our 54,000 employees in all major world markets, our companies specialize in consumer advertising, digital marketing, communications planning and media buying, public relations and specialized communications disciplines. Our agencies create customized marketing programs for clients that range in scale from large global marketers to regional and local clients. Comprehensive global services are critical to effectively serve our multinational and local clients in markets throughout the world as they seek to build brands, increase sales of their products and services, and gain market share. -

R3 China Agency Family Tree 2020-En-20200422

46,336 Local agencies (RMB 88,874 M revenue) China 324 MUltinational Agencies AGENCY FAMILY TREE (RMB 26,477 M revenue) 2020 LOCAL GROUPS INDEPENDENT LOCAL AGENCIES MULTINATIONAL AGENCIES BlueFocus 2019 Revenue Estimate: RMB 5,999 M WPP 2019 Revenue Estimate: RMB 6,918 M Beijing 2019 Revenue Estimate: RMB 12,369 M China East 2019 Revenue Estimate: RMB 18,097 M China north 2019 Revenue Estimate: RMB 8,435 M BLUEFOCUS GROUP: BlueDigital, Phluency, SNK Advertising, Insight PR, AKQA: AKQA NIELSEN 2019 Revenue Estimate: RMB 1,899 M BlueMedia (Domob, Madhouse, BlueVision), Bojie Media, Eyes Media, Creative Jiuyi, I'MNEXT, Yuanshan, Orange Group, Think3, Bang, JIANGSU Reeyee, Radi, J&J Intelligence Group, Easyads, TIANJIN Bo Ruo, Shen Du, Shuang Mu Ad, Tian Jian Ad, Burson Cohn Wolfe: Burson Cohn Wolfe Kingo, Jiebao Data, BlueFocus Entertainment Communications, La Feng Media, DHA Group, Pga-sip, Silverapple, Finsbury: Finsbury Rando, Feng's/Ribo, Sun&Sun Branding, Boda Siyuan, NO of Agencies: 2,725 NO of Agencies: 1,086 Seeder Ad, Fuyuan, Sheng Shi Tong Da Ad, Prophet Data, We Are Social, Metta Communications Dongdao, ShiPang Advertising Co., Ltd. LXU studio, Shi Chuan Ad, Nanjing MPI, Huajian Media, Cxeye, Yang Guang Lu Yi Media, Shangding Team, Geometry Global: Geometry, Geometry Dawson, Geometry Winline, 2019 Revenue Estimate: RMB 770 M Association: Behe, Blue Future, BlueStrategy, Blue Skyfall, BoldSeas, TAMNAAAA, Mos, Sun Communication, Service Plan, Jin Ding Ad, Wonderful100 Ad, T.C. Brand Design, Maihe Ad, Chuan Cheng Ad, Niad Ad Geometry -

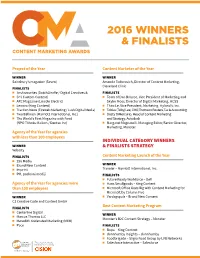

2016 Winners & Finalists

2016 WINNERS & FINALISTS Project of the Year Content Marketer of the Year WINNER WINNER Sainsbury’s magazine (Seven) Amanda Todorovich, Director of Content Marketing, Cleveland Clinic FINALISTS n #nsfavourites (DutchGiraffe / Digital Creatives & FINALISTS n G+J Custom Content) n Team of Dan Briscoe, Vice President of Marketing and n ARC Magazine (Lincoln Electric) Skyler Moss, Director of Digital Marketing, HCSS n Lenovo (King Content) n Thao Le, Vice President, Marketing, Hyland’s, Inc. n Traction News (Tireweb Marketing / Lush Digital Media) n Tobias (Toby) Lee, CMO,Thomson Reuters,Tax & Accounting n Two Bellmen (Marriott International, Inc.) n Dusty DiMercurio, Head of Content Marketing n The World’s First Magazine with Food and Strategy, Autodesk (NPO Tôhoku Kaikon / Dentsu Inc) n Margaret Magnarelli, Managing Editor/Senior Director, Marketing, Monster Agency of the Year for agencies with less than 100 employees INDIVIDUAL CATEGORY WINNERS WINNER & FINALISTS STRATEGY Velocity FINALISTS Content Marketing Launch of the Year n 256 Media n Brand New Content WINNER n Imprint Traveler – Marriott International, Inc. n PM, poslovni mediji FINALISTS n Future Ready Workforce – Dell Agency of the Year for agencies more n Hans Smallgoods – King Content than 100 employees n Microsoft Office Goes Big with Content Marketing for Microsoft by Column Five WINNER n Vardagspuls – Brand New Content C3 Creative Code and Content GmbH Best Content Marketing Program FINALISTS n Centerline Digital n Marcus Thomas LLC WINNER Monster’s B2C Content Strategy –