Statement of Committee Chairman Michael Mccaul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minority Views

MINORITY VIEWS The Minority Members of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence on March 26, 2018 submit the following Minority Views to the Majority-produced "Repo11 on Russian Active Measures, March 22, 2018." Devin Nunes, California, CMAtRMAN K. Mich.J OI Conaw ay, Toxas Pe1 or T. King. New York F,ank A. LoBiondo, N ew Jersey Thom.is J. Roonev. Florida UNCLASSIFIED Ileana ROS·l chtinon, Florida HVC- 304, THE CAPITOL Michnel R. Turner, Ohio Brad R. Wons1 rup. Ohio U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES WASHINGTON, DC 20515 Ou is S1cwart. U1ah (202) 225-4121 Rick Cr.,w ford, Arka nsas P ERMANENT SELECT C OMMITTEE Trey Gowdy, South Carolina 0A~lON NELSON Ellsr. M . S1nfn11ik, Nnw York ON INTELLIGENCE SrAFf. D IREC f()ti Wi ll Hurd, Tcxa~ T11\'10l !IV s. 8 £.R(.REE N At1am 8 . Schiff, Cohforn1a , M tNORllV STAFF OtR ECToq RANKIN G M EMtlER Jorncs A. Himes, Connec1icut Terri A. Sewell, AlabJma AndrC Carso n, lncli.1 na Jacki e Speier, Callfomia Mike Quigley, Il linois E,ic Swalwell, California Joilq u1 0 Castro, T exas De nny Huck, Wash ington P::iul D . Ry an, SPCAl([ R or TH( HOUSE Noncv r c1os1. DEMOC 11t.1 1c Lr:.11.orn March 26, 2018 MINORITY VIEWS On March I, 201 7, the House Permanent Select Commiltee on Intelligence (HPSCI) approved a bipartisan "'Scope of In vestigation" to guide the Committee's inquiry into Russia 's interference in the 201 6 U.S. e lection.1 In announc ing these paramete rs for the House of Representatives' onl y authorized investigation into Russia's meddling, the Committee' s leadership pl edged to unde1take a thorough, bipartisan, and independent probe. -

Policy & Legislative Outlook November 13, 2020 9 -- 11 AM CT

Policy & Legislative Outlook November 13, 2020 9 -- 11 AM CT Presented in partnership with the City of San Antonio, Department of Neighborhood and Housing Services 1 9:00 AM Event Kick-Off Welcome by Leilah Powell, Executive Director, LISC San Antonio 9:05 Keynote Panel 2020 Election Results & What to Expect in 2021 • Matt Josephs, SVP LISC Policy, Washington DC • Mark Bordas, Managing Partner, Aegis Advocacy, Austin TX San Antonio Policy & Legislative Outlook, November 13, 2020 2 2020 Election Outcomes Control of the White House Potential Cabinet Secretaries: Treasury, HUD and HHS Lael Brainard Raphael Bostic Karen Bass Eric Garcetti Vivek Murthy Mandy Cohen Sarah Bloom Keisha Lance Bottoms Michelle Lujan Raskin Grisham Control of the Senate 117th Congress Democrats Republicans 48 50 116th Congress Control of the House of Representatives 117th Congress Democrats Republicans 218 202 116th Congress 117th Congressional Leadership (Anticipated) House (pending leadership elections) Speaker of the House: Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) Majority Leader: Steny Hoyer (D-MD) Minority Leader: Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) Senate (pending elections results) Majority Leader: Mitch McConnell (R-KY) Minority Leader: Chuck Schumer (D-NY) 117th Congress: Senate and House Appropriations Committee Leadership (Anticipated) Senator Richard Senator Patrick Reps. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), Rep. Kay Granger Shelby (R-AL): Chair Leahy (D-VT): Marcy Kaptur (D-OH), and (R-TX): Ranking of the Senate Ranking Member of Debbie Wasserman Schultz Member of the Appropriations the Senate (D-FL) -

Case 1:19-Cv-00969 Document 1 Filed 04/05/19 Page 1 of 45

Case 1:19-cv-00969 Document 1 Filed 04/05/19 Page 1 of 45 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, United States Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515, Plaintiff, v. STEVEN T. MNUCHIN, in his official capacity as Secretary of the United States Department of the Treasury, 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue N.W. Washington, D.C. 20220, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY, 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue N.W. Washington, D.C. 20220, PATRICK M. SHANAHAN, in his official capacity as Acting Secretary of the United States Department of Defense, 1000 Defense Pentagon Case No. 19-cv-969 Washington, D.C. 20301, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, 1000 Defense Pentagon Washington, D.C. 20301, KIRSTJEN M. NIELSEN, in her official capacity as Secretary of the United States Department of Homeland Security, 245 Murray Lane S.W. Washington, D.C. 20528, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, 245 Murray Lane S.W. Washington, D.C. 20528, Case 1:19-cv-00969 Document 1 Filed 04/05/19 Page 2 of 45 DAVID BERNHARDT, in his official capacity as Acting Secretary of the United States Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20240, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, 1849 C Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20240, Defendants. COMPLAINT INTRODUCTION This case arises out of the unconstitutional actions taken by President Donald J. Trump’s Administration to construct a wall along the southern border of the United States. The Administration sought – and Congress denied – $5 billion to construct a wall along the southern border. -

OCTOBER 6, 2020 WASHINGTON, DC @Congressfdn #Democracyawards Table of Contents

AWARDS CELEBRATION OCTOBER 6, 2020 WASHINGTON, DC www.CongressFoundation.org @CongressFdn #DemocracyAwards Table of Contents 3 About the Congressional Management Foundation 3 Special Thanks 4 About the Democracy Awards 5 Virtual Awards Ceremony 6 Democracy Awards for Constituent Service 7 Democracy Awards for Innovation and Modernization 8 Democracy Awards for “Life in Congress” Workplace Environment 9 Democracy Awards for Transparency and Accountability 10 Finalists for the Democracy Awards 14 Democracy Awards for Lifetime Achievement 18 Staff Finalists for Lifetime Achievement 21 Selection Committee Biographies 24 Thank You to Our Generous Supporters 2 • CongressFoundation.org • @CongressFdn • #DemocracyAwards About the Congressional Management Foundation The Congressional Management Foundation (CMF) is a 501(c)(3) QUICK FACTS nonpartisan nonprofit whose mission is to build trust and effectiveness in Congress. • More than 1,100 staff from more than 300 congressional We do this by enhancing the performance of the institution, offices participate in the training legislators and their staffs through research-based education programs CMF conducts annually. and training, and by strengthening the bridge and understanding between Congress and the People it serves. • Since 2014 CMF has conducted 500 educational sessions with Since 1977, CMF has worked internally with Member, committee, more than 90,000 citizens on leadership, and institutional offices in the House and Senate to effectively communicating with identify and disseminate best practices for management, workplace Congress. environment, communications, and constituent services. • Since 2000, CMF has conducted CMF also is the leading researcher and trainer on citizen more than 500 strategic planning engagement, educating thousands of individuals and facilitating or other consulting projects with better understanding, relationships, and communications with Members of Congress and their staffs. -

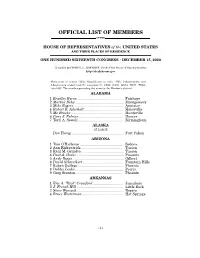

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E588 HON. WILL HURD HON. MICHAEL T. Mccaul HON. DAVID YOUNG HON. CHERI BUSTOS HON

E588 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks May 7, 2018 RECOGNIZING THE SAN ELIZARIO ties, CBO estimates that implementing H.R. Mr. Speaker, I would like to once again con- HIGH SCHOOL MEN’S SOCCER 5099 would have no significant effect on gratulate the Galena DeSoto House Hotel on TEAM spending by DHS. their 163rd anniversary and for their commit- Enacting H.R. 5099 would not affect direct spending or revenues; therefore, pay-as-you- ment to preserving its rich history. HON. WILL HURD go procedures do not apply. OF TEXAS CBO estimates that enacting H.R. 5099 f would not increase net direct spending or on- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES budget deficits in any of the four consecutive PERSONAL EXPLANATION Monday, May 7, 2018 10-year periods beginning in 2029. Mr. HURD. Mr. Speaker, I am pleased to H.R. 5099 contains no intergovernmental or private-sector mandates as defined in the HON. JEFF DENHAM offer my sincere congratulations to the San Unfunded Mandates Reform Act. OF CALIFORNIA Elizario High School Men’s Soccer Team for The CBO staff contact for this estimate is IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES winning the District 4–A Championship. This Mark Grabowicz. The estimate was reviewed milestone is truly a testament to the team, by H. Samuel Papenfuss, Deputy Assistant Monday, May 7, 2018 their dedicated work ethic, perseverance, and Director for Budget Analysis. talents. f Mr. DENHAM. Mr. Speaker, I missed votes I am proud to represent a group of young on April 27th to attend a funeral. Had I been TRIBUTE TO BETA SIGMA PHI men that are as determined and hard working present, I would have voted NAY on Roll Call as this team. -

Sen. John Cornyn Republican—Dec. 2, 2002 Sen. Ted Cruz Republican

TEXAS Sen. John Cornyn Sen. Ted Cruz of Austin of Houston Republican—Dec. 2, 2002 Republican—Jan. 3, 2013 Rep. Louie Gohmert Rep. Ted Poe of Tyler (1st District) of Atascocita (2nd District) Republican—6th term Republican—6th term 126 PICTORIAL.indb 126 6/15/15 7:53 AM TEXAS Rep. Sam Johnson Rep. John Ratcliffe of Plano (3rd District) of Heath (4th District) Republican—13th term Republican—1st term Rep. Jeb Hensarling Rep. Joe Barton of Dallas (5th District) of Ennis (6th District) Republican—7th term Republican—16th term 127 PICTORIAL.indb 127 6/15/15 7:53 AM TEXAS Rep. John Abney Rep. Kevin Brady Culberson of The Woodlands of Houston (7th District) (8th District) Republican—8th term Republican—10th term Rep. Al Green Rep. Michael T. McCaul of Houston (9th District) of Austin (10th District) Democrat—6th term Republican—6th term 128 PICTORIAL.indb 128 6/15/15 7:53 AM TEXAS Rep. K. Michael Conaway Rep. Kay Granger of Midland (11th District) of Fort Worth (12th District) Republican—6th term Republican—10th term Rep. Mac Thornberry Rep. Randy K. Weber, Sr. of Clarendon (13th District) of Friendswood (14th District) Republican—11th term Republican—2nd term 129 PICTORIAL.indb 129 6/15/15 7:53 AM TEXAS Rep. Rubén Hinojosa Rep. Beto O’Rourke of McAllen (15th District) of El Paso (16th District) Democrat—10th term Democrat—2nd term Rep. Bill Flores Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee of Bryan (17th District) of Houston (18th District) Republican—3rd term Democrat—11th term 130 PICTORIAL.indb 130 6/15/15 7:53 AM TEXAS Rep. -

Congressional Advocacy and Key Housing Committees

Congressional Advocacy and Key Housing Committees By Kimberly Johnson, Policy Analyst, • The Senate Committee on Appropriations . NLIHC • The Senate Committee on Finance . obbying Congress is a direct way to advocate See below for details on these key committees for the issues and programs important to as of December 1, 2019 . For all committees, you . Members of Congress are accountable to members are listed in order of seniority and Ltheir constituents and as a constituent, you have members who sit on key housing subcommittees the right to lobby the members who represent are marked with an asterisk (*) . you . As a housing advocate, you should exercise that right . HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL CONTACT YOUR MEMBER OF SERVICES CONGRESS Visit the committee’s website at To obtain the contact information for your http://financialservices.house.gov. member of Congress, call the U S. Capitol The House Committee on Financial Services Switchboard at 202-224-3121 . oversees all components of the nation’s housing MEETING WITH YOUR MEMBER OF and financial services sectors, including banking, CONGRESS insurance, real estate, public and assisted housing, and securities . The committee reviews Scheduling a meeting, determining your main laws and programs related to HUD, the Federal “ask” or “asks,” developing an agenda, creating Reserve Bank, the Federal Deposit Insurance appropriate materials to take with you, ensuring Corporation, government sponsored enterprises your meeting does not veer off topic, and including Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and following-up afterward are all crucial to holding international development and finance agencies effective meetings with Members of Congress . such as the World Bank and the International For more tips on how to lobby effectively, refer to Monetary Fund . -

State Delegations

STATE DELEGATIONS Number before names designates Congressional district. Senate Republicans in roman; Senate Democrats in italic; Senate Independents in SMALL CAPS; House Democrats in roman; House Republicans in italic; House Libertarians in SMALL CAPS; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface. ALABAMA SENATORS 3. Mike Rogers Richard C. Shelby 4. Robert B. Aderholt Doug Jones 5. Mo Brooks REPRESENTATIVES 6. Gary J. Palmer [Democrat 1, Republicans 6] 7. Terri A. Sewell 1. Bradley Byrne 2. Martha Roby ALASKA SENATORS REPRESENTATIVE Lisa Murkowski [Republican 1] Dan Sullivan At Large – Don Young ARIZONA SENATORS 3. Rau´l M. Grijalva Kyrsten Sinema 4. Paul A. Gosar Martha McSally 5. Andy Biggs REPRESENTATIVES 6. David Schweikert [Democrats 5, Republicans 4] 7. Ruben Gallego 1. Tom O’Halleran 8. Debbie Lesko 2. Ann Kirkpatrick 9. Greg Stanton ARKANSAS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES John Boozman [Republicans 4] Tom Cotton 1. Eric A. ‘‘Rick’’ Crawford 2. J. French Hill 3. Steve Womack 4. Bruce Westerman CALIFORNIA SENATORS 1. Doug LaMalfa Dianne Feinstein 2. Jared Huffman Kamala D. Harris 3. John Garamendi 4. Tom McClintock REPRESENTATIVES 5. Mike Thompson [Democrats 45, Republicans 7, 6. Doris O. Matsui Vacant 1] 7. Ami Bera 309 310 Congressional Directory 8. Paul Cook 31. Pete Aguilar 9. Jerry McNerney 32. Grace F. Napolitano 10. Josh Harder 33. Ted Lieu 11. Mark DeSaulnier 34. Jimmy Gomez 12. Nancy Pelosi 35. Norma J. Torres 13. Barbara Lee 36. Raul Ruiz 14. Jackie Speier 37. Karen Bass 15. Eric Swalwell 38. Linda T. Sa´nchez 16. Jim Costa 39. Gilbert Ray Cisneros, Jr. 17. Ro Khanna 40. Lucille Roybal-Allard 18. -

Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress

Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress AGRICULTURE, NUTRITION AND FORESTRY BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Pat Roberts, Kansas Debbie Stabenow, Michigan Mike Crapo, Idaho Sherrod Brown, Ohio Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont Richard Shelby, Alabama Jack Reed, Rhode Island Mitch McConnell, Kentucky Sherrod Brown, Ohio Bob Corker, Tennessee Bob Menendez, New Jersey John Boozman, Arkansas Amy Klobuchar, Minnesota Pat Toomey, Pennsylvania Jon Tester, Montana John Hoeven, North Dakota Michael Bennet, Colorado Dean Heller, Nevada Mark Warner, Virginia Joni Ernst, Iowa Kirsten Gillibrand, New York Tim Scott, South Carolina Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts Chuck Grassley, Iowa Joe Donnelly, Indiana Ben Sasse, Nebraska Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota John Thune, South Dakota Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota Tom Cotton, Arkansas Joe Donnelly, Indiana Steve Daines, Montana Bob Casey, Pennsylvania Mike Rounds, South Dakota Brian Schatz, Hawaii David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland Luther Strange, Alabama Thom Tillis, North Carolina Catherine Cortez Masto, Nevada APPROPRIATIONS John Kennedy, Louisiana REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC BUDGET Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Mitch McConnell, Patty Murray, Kentucky Washington Mike Enzi, Wyoming Bernie Sanders, Vermont Richard Shelby, Dianne Feinstein, Alabama California Chuck Grassley, Iowa Patty Murray, -

2020 Post-Election Outlook Introduction – a Divided Government Frames the Path Forward

2020 Post-Election Outlook Introduction – A Divided Government Frames the Path Forward ........................................................................3 Lame Duck .....................................................................................4 First 100 Days ...............................................................................7 Outlook for the 117th Congress and Biden Administration ............................................................12 2020 Election Results ............................................................ 36 Potential Biden Administration Officials ..................... 40 Additional Resources ............................................................. 46 Key Contacts ............................................................................... 47 Introduction – A Divided Government Frames the Path Forward Former Vice President Joe Biden has been elected to serve as the 46th President of the United States, crossing the 270 electoral vote threshold on Saturday, November 7, with a victory in Pennsylvania. His running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA), will be the first woman, first African- American and first South Asian-American to serve as Vice President. Their historic victory follows an election where a record number of voters cast ballots across a deeply divided country, as reflected in the presidential and closely contested Senate and House races. In the Senate, Republicans are on track to control 50 seats, Democrats will control 48 seats, and the final two Senate seats will be decided -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E588 HON. WILL HURD HON. MICHAEL T. Mccaul HON. DAVID YOUNG HON. CHERI BUSTOS HON

E588 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks May 7, 2018 RECOGNIZING THE SAN ELIZARIO ties, CBO estimates that implementing H.R. Mr. Speaker, I would like to once again con- HIGH SCHOOL MEN’S SOCCER 5099 would have no significant effect on gratulate the Galena DeSoto House Hotel on TEAM spending by DHS. their 163rd anniversary and for their commit- Enacting H.R. 5099 would not affect direct spending or revenues; therefore, pay-as-you- ment to preserving its rich history. HON. WILL HURD go procedures do not apply. OF TEXAS CBO estimates that enacting H.R. 5099 f would not increase net direct spending or on- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES budget deficits in any of the four consecutive PERSONAL EXPLANATION Monday, May 7, 2018 10-year periods beginning in 2029. Mr. HURD. Mr. Speaker, I am pleased to H.R. 5099 contains no intergovernmental or private-sector mandates as defined in the HON. JEFF DENHAM offer my sincere congratulations to the San Unfunded Mandates Reform Act. OF CALIFORNIA Elizario High School Men’s Soccer Team for The CBO staff contact for this estimate is IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES winning the District 4–A Championship. This Mark Grabowicz. The estimate was reviewed milestone is truly a testament to the team, by H. Samuel Papenfuss, Deputy Assistant Monday, May 7, 2018 their dedicated work ethic, perseverance, and Director for Budget Analysis. talents. f Mr. DENHAM. Mr. Speaker, I missed votes I am proud to represent a group of young on April 27th to attend a funeral. Had I been TRIBUTE TO BETA SIGMA PHI men that are as determined and hard working present, I would have voted NAY on Roll Call as this team.