Infratil Update September 2013 Issue No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand Broadband: Free TV's and Fridges - the Consumer Wins but Is It Sustainable?

MARKET PERSPECTIVE New Zealand Broadband: Free TV's and Fridges - The Consumer Wins but is it Sustainable? Peter Wise Shane Minogue Monica Collier Jefferson King Sponsored by Spark New Zealand Limited IDC OPINION The New Zealand telecommunications market is shifting; from a focus around better and faster connectivity, to service innovations and value. Consumers are enjoying better internet connectivity and a raft of competitive offers from more than 90 retailers. Retailers, however, are feeling the pinch of decreasing margins. Questions are starting to arise about the sustainability of such a competitive retail marketplace. Total telecommunications market revenues increased by 1.1% from NZ$5.361 billion in the year to December 2016 to NZ$5.421 billion in the year to December 2017. IDC forecasts that this growth will continue in future years with a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 1.4% to 2021. However, this growth disguises the true story of a market that is displaying extreme price pressure and competition in both fixed and mobile. Overall, ARPUs are either flat or declining in both broadband and mobile and in the broadband space Retail Service Providers (RSPs) continue to compete away any chance of strong, sustainable ARPU growth. New Zealand telecommunication's structural separation and national broadband plan have created new constructs and market dynamics. The UFB initiative has commoditised fibre in New Zealand. Consumer fibre plan prices have plummeted from averaging over NZ$200 per month in 2013 to around NZ$85 per month as at February 2018. Fibre is available to more than a million homes and premises, and over a third have made the switch. -

We're Making Life Better

Contact Energy Annual Limited Report 2019 WE’RE MAKING LIFE BETTER ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Contact is the human energy company with great ideas and smart solutions that make living easier for customers, now and in the future. This Annual Report is dated 12 August 2019 and is signed on behalf of the Board by: Robert McDonald Dame Therese Walsh Chair Chair, Audit Committee This report is printed on an environmentally responsible paper produced using Elemental Chlorine Free (ECF) FSC Certified pulp sourced from Sustainable & Legally Harvested Farmed Trees, and manufactured under the strict ISO14001 Environmental Management System. The inks used in printing this report have been manufactured from vegetable oils derived from renewable resources, and are biodegradable and mineral oil free. All liquid waste from the printing process has been collected, stored and subsequently disposed of through an accredited recycling company. CONTENTS This Year In Review ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Chair’s review .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................6 Chief Executive Officer’s review ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................7 -

The Climate Risk of New Zealand Equities

The Climate Risk of New Zealand Equities Hamish Kennett Ivan Diaz-Rainey Pallab Biswas Introduction/Overview ØExamine the Climate Risk exposure of New Zealand Equities, specifically NZX50 companies ØMeasuring company Transition Risk through collating firm emission data ØCompany Survey and Emission Descriptives ØPredicting Emission Disclosure ØHypothetical Carbon Liabilities 2 Measuring Transition Risk ØTransition Risk through collating firm emissions ØAimed to collate emissions for all the constituents of the NZX50. ØUnique as our dataset consists of Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions, ESG scores and Emission Intensities for each firm. ØCarbon Disclosure Project (CDP) reports, Thomson Reuters Asset4, Annual reports, Sustainability reports and Certified Emissions Measurement and Reduction Scheme (CEMAR) reports. Ø86% of the market capitilisation of the NZX50. 9 ØScope 1: Classified as direct GHG emissions from sources that are owned or controlled by the company. ØScope 2: Classified as indirect emissions occurring from the generation of purchased electricity. ØScope 3: Classified as other indirect GHG emissions occurring from the activities of the company, but not from sources owned or controlled by the company. (-./01 23-./014) Ø Emission Intensity = 6789 :1;1<=1 4 Company Survey Responses Did not Email No Response to Email Responded to Email Response Company Company Company Air New Zealand Ltd. The a2 Milk Company Ltd. Arvida Group Ltd. Do not report ANZ Group Ltd. EBOS Ltd. Heartland Group Holdings Ltd. Do not report Argosy Property Ltd. Goodman Property Ltd. Metro Performance Glass Ltd. Do not report Chorus Ltd. Infratil Ltd. Pushpay Holdings Ltd. Do not report Contact Energy Ltd. Investore Property Ltd. -

FNZ Basket 14102010

14-Oct-10 smartFONZ Basket Composition Composition of a basket of securities and cash equivalent to 200,000 NZX 50 Portfolio Index Fund units effective from 14 October 2010 The new basket composition applies to applications and withdrawals. Cash Portion: $ 1,902.98 Code Security description Shares ABA Abano Healthcare Group Limited 88 AIA Auckland International Airport Limited Ordinary Shares 6,725 AIR Air New Zealand Limited (NS) Ordinary Shares 2,784 AMP AMP Limited Ordinary Shares 432 ANZ Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited Ord Shares 212 APN APN News & Media Limited Ordinary Shares 1,759 APT AMP NZ Office Trust Ordinary Units 8,453 ARG Argosy Property Trust Ordinary Units 4,344 CAV Cavalier Corporation Limited Ordinary Shares 482 CEN Contact Energy Limited Ordinary Shares 1,508 EBO Ebos Group Limited Ordinary Shares 537 FBU Fletcher Building Limited Ordinary Shares 1,671 FPA Fisher & Paykel Appliances Holdings Limited Ordinary Shares 6,128 FPH Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Corporation Limited Ord Shares 3,106 FRE Freightways Limited Ordinary Shares 1,625 GFF Goodman Fielder Limited Ordinary Shares 3,990 GMT Macquarie Goodman Property Trust Ordinary Units 8,004 GPG Guinness Peat Group Plc Ordinary Shares 15,588 HLG Hallenstein Glasson Holdings Limited Ordinary Shares 430 IFT Infratil Limited Ordinary Shares 6,363 KIP Kiwi Income Property Trust Ordinary Units 10,287 KMD Kathmandu Holdings Limited Ordinary Shares 690 MFT Mainfreight Limited Ordinary Shares 853 MHI Michael Hill International Limited Ordinary Shares 1,433 NPX -

Infratil Investor Day

Infratil Investor Day 4 April 2014 Infratil Investor Day Trustpower Agenda • Performance developing points of difference • Focus on retail • Update on Australia © Trustpower Limited Highlights 2014 financial year • Acquisition of EDNZ accelerates retail multi-product strategy - 224,000 electricity customers - 54,300 telco services - 13,500 gas • Re-brand and launch into new geographies - Ready for metro launch • Significant progress on Snowtown Stage 2 wind farm • Completion of Esk Hydro © Trustpower Limited Consistent performance focus EBITDAF Return on adjusted capital © Trustpower Limited … and there are challenges • Demand remains flat • Government’s MoM programme – provides greater sector choice for investors • Labour / Green policy risk … TRUSTPOWER response © Trustpower Limited Re-launching the Brand – a point of difference • Stable, trustworthy and reliable • NZ owned and operated company • NZ based call centre • Excellent customer service • Rewards loyalty via Friends Gold (55% of customers) • Community involvement “So it comes down to customer service and what they do with their profit, which is where Trustpower gets two big ticks.” © Trustpower Limited Building brand value INTEGRATION Contact Energy Genesis Energy FUNCTIONAL CARE Pulse Energy Mercury Energy Meridian Energy Power Shop POWER COMPANY © Trustpower Limited Retail success – also means doing the basics well • Profitable customers that stay with you for a long time • Upsell must add value and / or increase loyalty • Cash is king and therefore processes must be excellent -

Annual Report 2013 ANNUAL REPORT Contact 2013

here Annual Report 2013 ANNUAL REPORT Contact 2013 ...is where we do our best work. CONTENTS Contact 2013 At Contact… We keep the lights burning, We are one of New Zealand’s largest listed companies but we operate with the same genuine concern for our the hot water flowing and the customers and communities as the smallest. We are BBQ fired up for around 566,000 integral to our customers’ lives – and our customers customers across the country. are integral to us. OUR BEST WORK 4 CASE STUDIES 30 CONTACT AT A GLANCE 12 HOW WE OPERATE 40 OUR BUSINESS MODEL 14 GOVERNANCE 56 WHERE WE OPERATE 16 REMUNERATION REPORT 62 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS 18 STATUTORY DISCLOSURES 65 CHAIRMAN & CEO’S REVIEW 20 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 69 OUR BOARD 26 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT 99 OUR LEADERSHIP TEAM 28 CORPORATE DIRECTORY 100 This Annual Report is dated 5 September 2013 and is signed on behalf of the Board by: Grant King Sue Sheldon Follow us at facebook.com/contactenergy Chairman Director OUR BEST WORK Contact 2013 “The kids think there’s always money on the card – they think nothing of a 30 minute shower.” Contact customer research Everyone in the family has unique habits when it comes to energy use. That can make it tough for households to manage their energy costs. We’ve created an easy-to-use online tool, called HEAT, to help our customers manage their energy and identify practical ways to save money on their energy bills. 4 Contact Energy LIMITED Annual Report 2013 Contact Energy LIMITED Annual Report 2013 5 OUR BEST WORK Contact 2013 “I’ll come home on a sunny day and she’ll have the dryer on for half an hour to do her bra and knickers.” Contact customer research Household energy costs vary from month to month as energy use fluctuates. -

Infratil Limited and Vodafone New Zealand Limited

PUBLIC VERSION NOTICE SEEKING CLEARANCE FOR A BUSINESS ACQUISITION UNDER SECTION 66 OF THE COMMERCE ACT 1986 17 May 2019 The Registrar Competition Branch Commerce Commission PO Box 2351 Wellington New Zealand [email protected] Pursuant to section 66(1) of the Commerce Act 1986, notice is hereby given seeking clearance of a proposed business acquisition. BF\59029236\1 | Page 1 PUBLIC VERSION Pursuant to section 66(1) of the Commerce Act 1986, notice is hereby given seeking clearance of a proposed business acquisition (the transaction) in which: (a) Infratil Limited (Infratil) and/or any of its interconnected bodies corporate will acquire shares in a special purpose vehicle (SPV), such shareholding not to exceed 50%; and (b) the SPV and/or any of its interconnected bodies corporate will acquire up to 100% of the shares in Vodafone New Zealand Limited (Vodafone). EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND INTRODUCTION 1. This proposed transaction will result in Infratil having an up to 50% interest in Vodafone, in addition to its existing 51% interest in Trustpower Limited (Trustpower). 2. Vodafone provides telecommunications services in New Zealand. 3. Trustpower has historically been primarily a retailer of electricity and gas. In recent years, Trustpower has repositioned itself as a multi-utility retailer. It now also sells fixed broadband and voice services in bundles with its electricity and gas products, with approximately 96,000 broadband connections. Trustpower also recently entered into an arrangement with Spark to offer wireless broadband and mobile services. If Vodafone and Trustpower merged, there would therefore be some limited aggregation in fixed line broadband and voice markets and potentially (in the future) the mobile phone services market. -

Download Our Credentials

Clare Capital Credentials About Us Clare Capital is an investment banking firm based in Wellington (NZ) specialising in mergers & acquisitions (M&A), capital raises, valuations, financial modelling, corporate finance advisory, private company benchmarking and technology insights. Clare Capital is an experienced team, with a reputation for original well-considered ideas backed by structured thinking and deep analytics. Clare Capital adds value by: ▪ Originating ideas for clients. ▪ Assisting clients by completing analysis of issues. ▪ Assisting clients to complete commercial transactions. Clare Capital The investment banking team provides advisory and transactional services across: www.clarecapital.co.nz ▪ Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A) – combining detailed financial analysis with extensive M&A experience to help our clients maximize outcomes. Level 5, 1 Woodward Street, PO Box 10269 ▪ Capital Management – advising clients on their capital raising activities. Wellington 6143, New Zealand ▪ Corporate Finance – combining fundamental corporate finance principles with real-world practical experience to provide clients with: valuations, capital structure advice, and option and incentive schemes and financial modelling. Contact: Mark Clare ▪ Strategic Advice – strategic and commercial advice to clients including: detailed strategic options analysis for clients facing key decisions and structuring and Mobile +64-21-470227 negotiating financial and commercial agreements. Email: [email protected] www.clarecapital.co.nz PAGE 1 Our Network -

Acquisition of Vodafone NZ

Acquisition of Vodafone NZ Investor Briefing Pack 14 May 2019 Disclaimer Disclaimer This presentation has been prepared by Infratil Limited (NZ company number 597366, NZX:IFT; ASX:IFT) (Company). To the maximum extent permitted by law, the Company, its affiliates and each of their respective affiliates, related bodies corporate, directors, officers, partners, employees and agents will not be liable (whether in tort (including negligence) or otherwise) to you or any other person in relation to this presentation. Information This presentation contains summary information about the Company and its activities which is current as at the date of this presentation. The information in this presentation is of a general nature and does not purport to be complete nor does it contain all the information which a prospective investor may require in evaluating a possible investment in the Company or that would be required in a product disclosure statement under the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013 or the Australian Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The historical information in this presentation is, or is based upon, information that has been released to NZX Limited (NZX) and ASX Limited. This presentation should be read in conjunction with the Company’s Annual Report, market releases and other periodic and continuous disclosure announcements, which are available at www.nzx.com, www.asx.com.au or infratil.com/for-investors/. United States of America This presentation is not an invitation or offer of securities for subscription, purchase or sale in any jurisdiction. In particular, this presentation does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any securities in the United States or any other jurisdiction in which such an offer would be illegal. -

Download Financial Statements

About These Financial Statements Statement of Comprehensive Income FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 These interim Financial Statements are for Contact, a group made up of Contact Energy Limited, the entities over which it has control or joint control and its associate. Unaudited Unaudited Audited 6 months ended 6 months ended Year ended Contact Energy Limited is registered in New Zealand under the Companies Act 1993. It is listed on the New Zealand Stock Exchange $m Note 31 Dec 2019 31 Dec 2018 30 June 2019 (NZX) and the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) and has bonds listed on the NZX debt market. Contact is an FMC reporting entity Revenue and other income A2 1,110 1,304 2,460 under the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013. Operating expenses A2 (889) (1,026) (1,955) Contact’s interim Financial Statements for the six months ended 31 December 2019 provide a summary of Contact’s performance Significant items A2 2 5 9 for the period and outline significant changes to information reported in the Financial Statements for the year ended 30 June 2019 Depreciation and amortisation C2 (110) (102) (205) (2019 Annual Report). The Financial Statements should be read with the 2019 Annual Report. Net interest expense B4 (28) (39) (70) The Financial Statements have been prepared: Profit before tax 85 142 239 in millions of New Zealand dollars (NZD) unless otherwise stated in accordance with New Zealand generally accepted accounting practice (GAAP) and comply with NZ IAS 34 Interim Financial Tax expense (26) (43) (69) Reporting Profit from continuing operations 59 99 170 using the same accounting policies and significant estimates and critical judgments disclosed in the 2019 Annual Report, Discontinued operation except as disclosed in note C2 with certain comparative amounts reclassified to conform to the current period’s presentation. -

Wellington's Links with the World

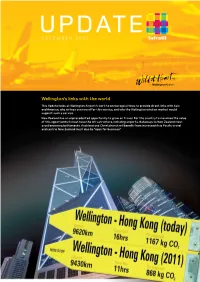

DECEMBER 2007 Wellington’s links with the world This Update looks at Wellington Airport’s work to encourage airlines to provide direct links with Asia and America, why airlines can now offer this service, and why the Wellington aviation market would support such a service. New Zealand has an unprecedented opportunity to grow air travel. For the country to maximise the value of this opportunity it must have the infrastructure, including airports. Gateways to New Zealand must avoid becoming bottlenecks. Auckland and Christchurch will benefit from increased Asia Pacific travel and central New Zealand must also be “open for business”. www.Infratil.com Air services matter Global Economic Activity (GEA) and world population within a 3.5 hour flying time PARIS CHICAGO 26% of world GEA 15% of world 32% of 25% of population HONG KONG world GEA world GEA 42% of world 7% of world population population WELLINGTON 1% of world GEA 0.4% of world population New Zealand is the furthest away place in the world. Draw a circle on a map to show 3.5 hours flying time from New Zealand and the circle captures 0.4% of the world’s population. The benefits and barriers of better connectivity are apparent from doing the same exercise centred on Hong Kong (42% of the world’s population and 32% of global economic activity), Paris (15% of the people, 26% of the economy) and Chicago (7% of the people and 25% of the world’s economy). A direct Wellington-Hong Kong air service would reduce travel time by at least three hours (six to seven if the service is via Sydney rather than Auckland). -

Kernel NZ 20 Fund for the Month Ended 30 April 2021

Kernel NZ 20 Fund For the month ended 30 April 2021 Fund overview What does the fund invest in? The Fund provides investors with a diversified exposure across Sector mix a range of sectors including utilities, real estate, This shows the sectors that the fund currently invests in: telecommunication and healthcare to 20 of the largest companies listed in New Zealand. Large and liquid, many of Health Care 30.1% these companies export globally and collectively account for Utilities 21.1% over 80% of the value of the entire investable NZ stockmarket. Industrials 16.9% Communication Services 10.7% Key information Real Estate 6.0% • Index tracked: S&P/NZX 20 Index Materials 5.8% • Number of constituents: 20 Consumer Staples 5.5% • Distribution frequency: Quarterly Consumer Discretionary 2.6% Energy 1.3% • Management fee: 0.39% Cash 0.0% • Inception: 28th August 2019 • Indicative yield: 2.02% How to use Kernel NZ 20 Fund The NZ 20 fund can be used in a variety of investment Top 10 investments strategies, for example: % of fund’s Company • A core allocation to NZ equities net asset value • A tactical exposure to NZ blue-chips Fisher & Paykel Healthcare 17.95% • A low cost alternative to other active managers Auckland International Airport 8.81% Spark 7.83% Performance Meridian Energy 6.43% Fund after Index Net tracking Mainfreight 5.88% fees difference Fletcher Building 5.76% 1 month 1.17% 1.20% -0.03% Ryman Healthcare 5.66% 3 months -4.20% -4.11% -0.09% Contact Energy 5.54% 6 months 4.19% 4.43% -0.24% The a2 Milk Company 5.46% 1 year 17.25% 17.34% -0.09% Infratil 4.96% 3 years 17.51% Current cash & equivalents = 0.01% 5 years 15.60% 10 years 16.43% Further information Fund returns before tax and assuming distributions reinvested.