Eric Anderson, “'I Used to Think Women Were Weak”: Orthodox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPORT and VIOLENCE a Critical Examination of Sport

SPORT AND VIOLENCE A Critical Examination of Sport 2nd Edition Thomas J. Orr • Lynn M. Jamieson SPORT AND VIOLENCE A Critical Examination of Sport 2nd Edition Thomas J. Orr Lynn M. Jamieson © 2020 Sagamore-Venture All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. Publishers: Joseph J. Bannon/Peter Bannon Sales and Marketing Manager: Misti Gilles Director of Development and Production: Susan M. Davis Graphic Designer: Marissa Willison Production Coordinator: Amy S. Dagit Technology Manager: Mark Atkinson ISBN print edition: 978-1-57167-979-6 ISBN etext: 978-1-57167-980-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020939042 Printed in the United States. 1807 N. Federal Dr. Urbana, IL 61801 www.sagamorepublishing.com Dedication “To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme. No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea, though many there be that have tried it.” Herman Melville, my ancestor and author of the classic novel Moby Dick, has passed this advice forward to myself and the world in this quote. The dynamics of the sports environment have proven to be a very worthy topic and have provided a rich amount of material that investigates the actions, thoughts, and behaviors of people as they navigate their way through a social environment that we have come to know as sport. By avoiding the study of fleas, I have instead had to navigate the deep blue waters of research into finding the causes, roots, and solutions to a social problem that has become figuratively as large as the mythical Moby Dick that my great-great uncle was in search of. -

Ike Hi-Life December 2016 Vol

EARTHQUAKE OLD VS. NEW IS CHEERLEADING SURVIVOR WORKS HIP HOP: WHAT A SPORT? 2 TO ACHIEVE GOALS 3 DOES PIKE THINK? 4 PIke High School 5401 W. 71st St. Indianapolis, IN 46268 ike Hi-Life December 2016 Vol. 75 Issue 3 Is the dress code fair? Many believe it disproportionately targets girls, while others think it’s OK HALEIGH STINER guys, it should be stricter for things like sagging, what kind Editor-in-chief of logos and symbols and The dress code policies words are written on them,” at many schools around the science teacher Ms. Danielle country have caused a lot of Lord said. controversy. Pike also has a Brown, who personally has dress code that some people been called out for wearing disagree with. Many people leggings with a jacket, agrees find the dress code sexist. with Ms. Lord. “(The dress code) is mostly “I feel like it should be less focused on (girls),” junior Dar- focused on females,” Brown ling Brown said. said. “In general, it’s just kind For example, Brown said, of unnecessary.” the rules about showing Certain students feel it shoulders and wearing leg- Sarah Medrano / Hi-Life should just be enforced dif- Juniors Michael Condon, Kiran Patel, Monica Pineda and gings target females more ferently. Anisha Mahenthiran wear hooded sweatshirts without the than males. “I don’t really think the hoods up, abiding by the school dress code. Junior Elizabeth Bowers dress code specifically should said, in reference to the dress as girls cannot wear leggings like junior Natalie Benedict, be changed. I just think the code, “The sexualization of without proper coverage. -

13-Cheerleading

CHEERLEADING The presence of a strong cheerleading team has been an feature of Maine athletics for more than half a century. Although the activity traditionally attracts more women than men, the first individual to receive a varsity “M” for cheerleading was a male, Don Green in the 1932-33 academic year. During the 1930s and well into the 1940s, most cheerleaders were males. Their cheering efforts, for the most part, were limited to football games. The first woman to receive a cheerleading “M” was Mary Belle Tufts in the 1947-48 college year. The activity gained in numbers during the 1950s with squads averaging between nine and 15 per year. The Athletic Board, responsible for determining “M” recipients each year, presented the varsity “M”, or an equivalent award, to cheerleaders until the end of the 1959-60 college year. At that time, for reasons which cannot be documented, the Board reversed itself and no “M” awards were made during the next 21 years. In 1981, however, Assoc. Director of Athletics Woody Carville, who was responsible for cheerleading activities among his many duties, was able to persuade the Board to re-instate the “M” award for members of cheering teams. The number of cheerleaders who gained recognition for their efforts grew in numbers significantly during the 1980s, primarily due to the creation of a squad for football games and and a second unit for basketball games. In the 1989-90 college year, some 31 cheering awards were given. Then the rules changed again. The Board decided to award the “M” only to those cheerleaders who were members of both teams. -

Cheer Manual

MISSOURI STATE HIGH SCHOOL ACTIVITIES ASSOCIATION 1 North Keene St. P. O. Box 1328 Columbia, Missouri 65205-1328 Telephone: (573) 875-4880; Fax Number: (573) 875-1450; E-Mail: [email protected] EXECUTIVE STAFF Dr. Kerwin Urhahn, Executive Director George Blase, Assistant Executive Director Stacy Schroeder, Assistant Executive Director Fred Binggeli, Assistant Executive Director Dale Pleimann, Assistant Executive Director *Davine Davis, Assistant Executive Director Kevin Garner, Assistant Executive Director Rick Kindhart, Assistant Executive Director Craig Long, Chief Financial Officer Janie Barck, Administrative Assistant * MSHSAA CONTACT PERSON FOR CHEERLEADERS TABLE OF CONTENTS Purpose and Philosophy.............................................................. PAGE 3 SECTION 1: Using This Manual................................................. PAGE 4 SECTION 2: General Information & Eligibility Standards ........... PAGE 4 SECTION 3: Conduct & Sportsmanship Suggestions ................ PAGE 7 SECTION 4: Cheerleading Policies For State Tournaments ...... PAGE 12 SECTION 5: Uniforms ................................................................ PAGE 18 SECTION 6: Cheerleading Clinics.............................................. PAGE 19 SECTION 7: Prevention and Care of Injuries ............................. PAGE 19 SECTION 8: Points of Emphasis................................................ PAGE 20 SECTION 9: Ethics..................................................................... PAGE 21 APPENDIX A: Techniques for Positive Crowd -

Sport, Exercise and Leisure New and Key Titles 2013

ROUTLEDGE Sport, Exercise and Leisure New and Key Titles 2013 www.routledge.com/sport Dear Reader, Welcome to the Sport, Exercise and Leisure catalogue 2013. This year brings some exciting new editions of existing textbooks, including An Introduction to Sports Coaching 2nd edition and Sports Development 3rd edition, and important new handbooks from a range of disciplines, including the Routledge Handbook of Sports Communication and the Routledge Handbook of Leisure Studies. Our publishing programme in sport, exercise and leisure continues to go from strength to strength, and I hope that the course guide presented in the catalogue (page 2) gives you an idea of the number of textbooks that we’re now publishing across each of the sub-disciplines within the area for use on your courses. Remember, our textbooks are available on inspection – if you find a book of interest that you would like to use on your course, request your complimentary exam copy and we’ll ensure that it is sent out to you as a priority. If you would like to find out more about our publishing programme, or have an idea for a new book, please do not hesitate to get in contact with me. Best wishes, Simon Whitmore Senior Commissioning Editor, Sport and Leisure Studies NeI electrW N ON teract Ic text Ive INTRODUCTION TO BOO SPORTS BIOMECHANICS 3RD EDITION k Analysing Human Movement Patterns by Roger Bartlett Introduction to Sports Biomechanics is an Highly illustrated throughout, with theoretical accessible and comprehensive guide to all of the principles discussed in the context of real biomechanics topics covered in an undergraduate sporting situations, every chapter contains cross sports and exercise science degree. -

Cheerleading Camp

Cheerleading camp TUTTI I LIVELLI! CHEERLEADING CAMP organizzato dalla squadra "Rainbow cheer", vincitrice di numerosi titoli nazionali, argento agli Europei e partecipazione ai Mondiali. A B L E V I O S U L LAGO DI COMO ! Allenati CENTRO SPORTIVO TALBOT dagli 8 ai 18 anni C O N N O I ! DAL 5 AL 9 LUGLIO Esibizione finale sabato 10.7 Allenati da: BENEDETTA SITZIA coach della Nazionale Italiana 2017 CELINE MANDIA atleta ai Mondiali in Florida ENRICO POZZO olimpionico www.sportarcobaleno.it di ginnastica artistica Per Informazioni dettagliate 3488123417 Ilaria - [email protected] Nella suggestiva cornice del lago di Como, in uno spazio dedicato interamente ai bambini e ragazzi, nasce il progetto di Bluelake, una comunità creativa, originale e fantasiosa, una sorta di villaggio fantastico, un luogo di relazioni, conoscenze, scambi, apprendimenti e divertimento. Per il periodo di luglio, il villaggio propone una serie di campi estivi della durata di una settimana, tutti differenti tra di loro, che toccheranno ambiti diversi e spazieranno dallo sport, alla natura, al circo, alla musica, alla lettura, alla manualità. Ogni attività esplorerà un linguaggio specifico e sarà strutturata in modo da coinvolgere attivamente i bambini e i ragazzi in nuove scoperte. E’ possibile, qualora ci siano posti, accedere anche per un giorno solo. Alla sera verrà inviato un report fotografico della giornata trascorsa 1 settimana – 5/9 LUGLIO 2021 L’ATTIVITA’ CAMP SPORTIVO DI CHEERLEADING per bambini e ragazzi dagli 8 ai 18 anni Vuoi provare ad essere un cheerleader per una settimana? La Società Sportiva Dilettantistica Arcobaleno è specializzata in questa attività! Sperimenta insieme a noi le tecniche base del cheer, sia che tu sia già un atleta sia che tu provi la prima volta. -

History of Cheerleading Originates from the United States in the Late 1880'S with Your Average Crowd Yelling and Chanting to Encourage Their Team

The history of cheerleading originates from the United States in the late 1880's with your average crowd yelling and chanting to encourage their team. No one is quite sure how they documented that it was the first cheer ever but credit is given to Princeton University in 1884 for coming up with a Princeton cheer and marking there place in cheerleading history. Then a few years later, the Princeton grad Tom Peebles brought cheering to the University of Minnesota. But it wasn't until 1898 that fellow University of Minnesota student Johnny Campbell directed what was the very first cheer ever in November of 1898. The story is that Minnesota was having such a terrible football season that people felt the need to come up with positive chants and cheering was born. Minnesota went on to organize a male cheer squad in 1903 and organized the first cheerleading fraternity in the history of cheerleading, Gamma Sigma. Ironically enough cheerleading started out as an all male sport, it was felt there deep loud voices were more projecting than a woman's voice. It wasn't until the 1920's that women became much more involved in cheerleading and began to incorporate gymnastics, pyramids and throws. Today, youth cheerleading is predominantly made up of female cheerleaders however college cheerleading is still about fifty percent male. Well, the students cheered all they could for Minnesota yet they still got beat. It was a student's scientific thesis that positive fan support would actually help send positive energy toward there team and assist them in winning. -

Cheerleader Gives up NFL for Her Faith Sumter’S Kristan Ware Says Christianity, Virginity Made Her a Target

S.C. prison chief faces Senate Subcommittee A6 Carolina Backcountry Springtime on Saturday Learn about weaving, blacksmithing, SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 18th-century weaponry and more A2 FRIDAY, MAY 11, 2018 75 CENTS Cheerleader gives up NFL for her faith Sumter’s Kristan Ware says Christianity, virginity made her a target BY ADRIENNE SARVIS home in dance studios. versation because she did not have [email protected] Along with her love for dance and one of her own. cheerleading, Ware has even more When asked why she didn't have a Faith is something that a lot of peo- passion for Christ. playlist, Ware decided to answer hon- ple carry with them everywhere they But, while being on the Miami Dol- estly and told her teammates she is go, including a former Miami Dol- phins cheerleading team gave her the waiting until marriage. phins cheerleader who was allegedly opportunity to do what she loved, the And though her teammates did not singled out for refusing to take God job later caused her distress. seem to mind her personal decision, out of her life for the sake of the Ware said her troubles began after she said the team staff made it a topic team. a trip to London in 2015 during her of discussion during Ware’s audition Though she moved a lot growing up second year with the Dolphins when for next season. in a military family, 27-year-old other cheerleaders were discussing Ware was baptized on April 10, Kristan Ann Ware of Sumter was their sex playlists. -

Elem. & Middle School Cheerleading Rules

Department of Recreation & Community Services 5225 W. Vliet Street, Milwaukee, WI 53208 (414) 475-8180 • mps.milwaukee.k12.wi.us ELEM. & MIDDLE SCHOOL CHEERLEADING RULES Revised 11/19/19 Sportsmanship - Unsportsmanlike conduct may result in ejection from the contest. Officials, coaches, parent, players, and fans should always display leadership and sportsmanship qualities. Any players or coaches ejected from the game by game officials/staff for unsportsmanlike conduct will be suspended until their case is reviewed by the Youth Sports Office, in which the final disposition of the case will then be made. Sports Coordinators are required to check with the Youth Sports Office prior to allowing the player, coach, or spectator in question continue participation in Youth Sports Activities. A participant, coach, or other team attendant must not commit an unsporting act. This includes but is not limited to, acts or conduct such as: Disrespectfully addressing or contacting an official or gesturing in such a manner as to indicate resentment. Using profane or inappropriate language. Baiting or taunting an opponent. Facility Reminders – Dogs are NOT permitted at any MPS/Milwaukee Recreation Building or Playfield. Smoking is prohibited during MPS/Milwaukee Recreation Youth Sports Activities (Including E-cigarettes) Weapons are NOT permitted at any MPS/Milwaukee Recreation Building or Playfield. Game Re-Scheduling/Cancellations - All school sport coordinators, coaches, or applicable staff will be notified of any schedule changes or game cancellations via email. Revised schedules will be posted on the MPS Recreation Website: www.MilwaukeeRecreation.net Section 1- Before the Game Article 1 - Rules are created by the MPS/Milwaukee Recreation Youth Sports Office, and can be altered at any time to improve the safety and understanding of the game. -

Wyfc 2021 Registration Form

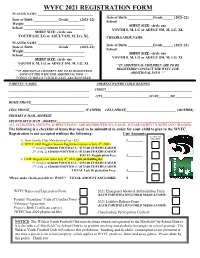

WYFC 2021 REGISTRATIONCHEERLEADER FORMNAME PLAYER NAME __________________________________ _______________________________________________ Date of Birth ______________Grade______ (2021-22) Date of Birth ______________Grade______ (2021-22) School __________________________________ Weight__________________________________ SHIRT SIZE: circle one School __________________________________ YOUTH S, M, LG or ADULT SM, M, LG, XL SHIRT SIZE: circle one YOUTH S,M, LG or ADULT SM, M, LG, XL CHEERLEADER NAME _______________________________________________ PLAYER NAME __________________________________ Date of Birth ______________Grade______ (2021-22) Date of Birth ______________Grade______ (2021-22) School __________________________________ Weight__________________________________ SHIRT SIZE: circle one School __________________________________ YOUTH S, M, LG or ADULT SM, M, LG, XL SHIRT SIZE: circle one YOUTH S, M, LG or ADULT SM, M, LG, XL **IF ADDITIONAL CHILDREN ARE TO BE REGISTERED CONTACT THE WYFC FOR **IF ADDITIONAL CHILDREN ARE TO BE REGISTERED ADDITIONAL INFO. ** CONTACT THE WYFC FOR ADDITIONAL INFO. ** COPIES OF BIRTH CERTIFICATES ARE REQUIRED PARENTS’ NAMES ADDRESS WHERE CHILD RESIDES ________________________________________ _______________ STREET_ __________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________ _________ CITY______ __________________________STATE________ZIP____________ HOME PHONE___________________________________ CELL PHONE__________________________________ (FATHER) CELL PHONE_______________________________ -

Cheerleading Handbook

2021‐2022 Oregon School Activities Association Cheerleading Handbook Peter Weber, Publisher Kelly Foster, Editor Published by OREGON SCHOOL ACTIVITIES ASSOCIATION 25200 SW Parkway, Suite 1 Wilsonville, OR 97070 503.682.6722 http://www.osaa.org How to find information in the Cheerleading Handbook This handbook can be found on the OSAA website. Wording that has been changed from previous years is indicated by bold italic lettering. Linked references to other sections are shaded and Questions and Answers are shaded. OSAA Mission Statement The mission of the OSAA is to serve member schools by providing leadership and state coordination for the conduct of interscholastic activities, which will enrich the educational experiences of high school students. The OSAA will work to promote interscholastic activities that provide equitable participation opportunities, positive recognition and learning experiences to students, while enhancing the achievement of educational goals. Non-Discrimination Policy (Executive Board Policies, Revised July 2019) A. The Oregon School Activities Association does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, national origin, marital status, age or disability in the performance of its authorized functions, and encourages its member schools, school personnel, participants and spectators to adopt and follow the same policy. B. A claim of discrimination against a member school shall be brought directly to the member school of concern. C. Any party that believes he/she has been subjected -

Scientific Programme: Plenary Sessions

Scientific programme: Plenary sessions [PS-PL] Plenay Sessions [PS-PL01] Healthy Ageing - Does Exercise Matter? 23.06.2010, Start: 18:00, Lecture room: "Hall 1" Chair: Wagenmakers Anton, The University of Birmingham [GB] AID: 1999 - ROLE OF EXERCISE IN AGE-RELATED CHANGES IN MUSCLE AND MATRIX Kjaer, M. [DENMARK] Read Updated: 17.06.2010 11:23:40 AID: 1579 - COGNITION, MEMORY AND WELL-BEING van Praag, H. [UNITED STATES] Read Updated: 17.06.2010 11:23:52 [PS-PL02] Role of Exercise in Appetite Regulation 24.06.2010, Start: 12:00, Lecture room: "Hall 1" Chair: Jeukendrup Asker, University of Birmingham [GB] AID: 1952 - THE ROLE OF EXERCISE IN APPETITE REGULATION. Blundell, J. [UNITED KINGDOM] Read Updated: 09.06.2010 23:12:45 AID: 1969 - ACTIVITY, INACTIVITY AND HORMONAL REGULATION OF APPETITE Braun, B. [UNITED STATES] Read Updated: 09.06.2010 23:13:07 [PS-PL03] Expertise and Skill Learning in Sport and Physical Activity 25.06.2010, Start: 12:00, Lecture room: "Hall 1" Chair: Williams Andrew Mark, Liverpool John Moores University [GB] AID: 1214 - DELIBERATE PRACTICE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF ELITE SPORT PERFORMANCE Ericsson, K.A. [UNITED STATES] Read Updated: 09.06.2010 22:58:16 AID: 2001 - ON THE NATURE OF SKILL ACQUISITION: BEYOND THE THREE-STAGE MODEL Beek, P. [NETHERLANDS] Read Updated: 09.06.2010 22:58:15 [PS-PL04] Optimizing Elite Performance 26.06.2010, Start: 12:00, Lecture room: "Hall 1" Chair: Müller Erich, University of Salzburg [AT] AID: 1524 - THE ROLE OF SPORTS SCIENCE IN OPTIMISING ELITE ATHLETE PERFORMANCE Hahn, A. [AUSTRALIA] Read Updated: 09.06.2010 23:22:01 AID: 1998 - SPORT PSYCHOLOGICAL CONCEPTS FOR OPTIMIZING ELITE PERFORMANCE IN AUSTRIA Amesberger, G.