Understanding Auden: the Workings of Satire and Humour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET of the THIRTIES

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET OF THE THIRTIES THE coMPLETION OF JoHN LEHMANN's autobiography with I Am My Brother (1960), begun with The Whispering Gallery (1955), brings back to mind, among a score of other largely forgotten matters, the fact that there were angry young poets in England long before those of last year-or was it year before last? The most outspoken of the much earlier dissident young verse writers were probably the three who made up the so-called "Oxford group", W. ·H. Auden, Stephen Spender, and C. Day Lewis. (Properly speaking they were never a group in col lege, though they knew one ariother as undergraduates and were interested in one another's work.) Whether taken together or singly, .they differed markedly from the young poets who have recently been given the label "angry". What these latter day "angries" are angry about is difficult to determine, unless indeed it is merely for the sake of being angry. Moreover, they seem to have nothing con structive to suggest in cure of whatever it is that disturbs them. In sharp contrast, those whom they have displaced (briefly) were angry about various conditions and situations that they were ready and eager to name specifically. And, as we shall see in a moment, they were prepared to do something about them. What the angry young poets of Lehmann's generation were angry about was the heritage of the first World War: the economic crisis, industrial collapse, chronic unemployment, and the increasing tP,reat of a second World War. -

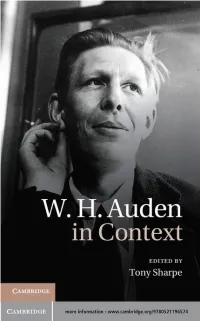

Sharpe, Tony, 1952– Editor of Compilation

more information - www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT W. H. Auden is a giant of twentieth-century English poetry whose writings demonstrate a sustained engagement with the times in which he lived. But how did the century’s shifting cultural terrain affect him and his work? Written by distinguished poets and schol- ars, these brief but authoritative essays offer a varied set of coor- dinates by which to chart Auden’s continuously evolving career, examining key aspects of his environmental, cultural, political, and creative contexts. Reaching beyond mere biography, these essays present Auden as the product of ongoing negotiations between him- self, his time, and posterity, exploring the enduring power of his poetry to unsettle and provoke. The collection will prove valuable for scholars, researchers, and students of English literature, cultural studies, and creative writing. Tony Sharpe is Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University. He is the author of critically acclaimed books on W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Vladimir Nabokov, and Wallace Stevens. His essays on modernist writing and poetry have appeared in journals such as Critical Survey and Literature and Theology, as well as in various edited collections. W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT edited by TONY SharPE Lancaster University cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 © Cambridge University Press 2013 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

First Name Initial Last Name

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Sarah E. Fass. An Analysis of the Holdings of W.H. Auden Monographs at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Rare Book Collection. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. April, 2006. 56 pages. Advisor: Charles B. McNamara This paper is an analysis of the monographic works by noted twentieth-century poet W.H. Auden held by the Rare Book Collection (RBC) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It includes a biographical sketch as well as information about a substantial gift of Auden materials made to the RBC by Robert P. Rushmore in 1998. The bulk of the paper is a bibliographical list that has been annotated with in-depth condition reports for all Auden monographs held by the RBC. The paper concludes with a detailed desiderata list and recommendations for the future development of the RBC’s Auden collection. Headings: Auden, W. H. (Wystan Hugh), 1907-1973 – Bibliography Special collections – Collection development University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Rare Book Collection. AN ANALYSIS OF THE HOLDINGS OF W.H. AUDEN MONOGRAPHS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL’S RARE BOOK COLLECTION by Sarah E. Fass A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. -

Anti-Romantic Elements in the Biographical-Critical Poems of W. H. Auden's Another Time

RICE UNIVERSITY ANTI-ROMANTIC ELBiENTS IN THE BIOGRAPHICAL-CRITICAL . POEMS OF W. H. AUDEN’S ANOTHER TIME by Sarah Lilly Terrell A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS Thesis Director’s signature* l/tyk&bjL /Al. — Houston, Texas June 1966 ABSTRACT ANTI-ROMANTIC ELEMENTS IN THE BIOGRAPHICAL-CRITICAL POEMS OF W. H. AUDEN’S ANOTHER TIME by Sarah Lilly Terrell W. H. Auden first published the volume of poems entitled Another Time on February 7, 1940. There has been no study of the volume as an artistic entity, and only a few of the poems have received detailed commentary. This thesis will consider a selected group of poems from Another Time, the biographical-critical poems, in some detail. They have been selected for major emphasis because they reflect the dominant concerns of the volume. Furthermore, because each biographical portrait is based on an informed knowledge of the life and work of the writer it depicts, the reader must be similarly informed before he can appreciate the richness of reference and astuteness of judgment which characterize those poems. The poems will be viewed from two perspectives: that sug¬ gested by Auden's prose writings on Romanticism and that provided by the context of the volume as a whole. The second chapter of this thesis surveys the wealth of primary sources in prose available to the critic interested in Auden's attitude towards Romanticism. The prose written from 1937-1941 is pervaded by Auden's concern with the implications of Romanticism. The address given at Smith College in 1940 contains Auden's most explicit statement of the ABSTRACT (Cont'd.) relationship of Romanticism to the then current political situation* The urgency of his preoccupation results from his conviction that the Romantics1 failure to grasp the proper relationship of freedom to nec¬ essity has an immediate and direct bearing on the rise of fascism* This preoccupation appears repeatedly in the many book reviews Auden wrote during this period. -

1934 to 1960

THE BIRDS AtTn THE BEASTS IN AUDEJ:1: A STUDY OF THE USE OF ANHiAI IEAGERY IN TIIE l\fO~J -DRAr:AT Ie POETRY OF "r1. H. AUDEN FRO}: 1934 TO 1960 AN HONORS THESIS SUBHITTED TO THE HONORS CO:r:r:I~TEE lIT PART rAL FUIJFILL!·::ENT OF T3E REQUIRE1-:ENTS FOR ~rHE DEGREE BACHELOR OF SCIENCE E~ E:GUGATION BY OLGA K. DF-'JT INO ADVISER - JOSEPH SATTER1ir~nTE BALL STATE U~IVERSITY I,lUNarE, INDIANA AUGUST, 1965 TEE BIRDS A~m TEiE BEASTS IN AUDE1r The rerutation of W. H. Auden as a poet rests not on the publication of several widely quoted and anthologized poems, but on a consistent and diversified output of technically e~·~cellent and relevant poetry over a nu!::ber of years (1930-1964). Though l;:an;.r of Auden t s individual ~:oems and lines are neDorable, it is rather the recurring patterns of his imagery which catch and hold the attention of his readers and critics. This paper will attempt to deal with one aSl_ect of Auden t S imar:;cry: his 1:!::ages of t::e animal world, and to trace the changes i~ this imagery as it corresponds to Audents ideological evolution froe the position of left-wing, near-Marxist to his positive acceptance of Christianity in the early 1940's. Thouc;h much has been written about various images which perrr,eate the poetry of 'tT. H. Auden--tllB early l)ervasi VB 1mrfare I:;otif, t!:e detective and spy inagery, and the Rilke-like Ithul!lan landscape" technique--crit:.cs have for the most part ignored uhat Randall Jarrell called Auden's "endless procession of birds and beasts"l as the -- lRandall Jarrell, t1Changes of Attitude and Rhetoric in AUden's roetry", Southern Reviel", Autumn, 1941, :po 329. -

The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden This volume brings together specially commissioned essays by some of the world’s leading experts on the life and work of W. H. Auden, one of the major English-speaking poets of the twentieth century. The volume’s contributors include a prize-winning poet, Auden’s literary executor and editor, and his most recent, widely acclaimed biographer. It offers fresh perspectives on his work from new and established Auden critics, alongside the views of specialists from such diverse fields as drama, ecological and travel studies. It provides scholars, students and general readers with a comprehensive and authoritative account of Auden’s life and works in clear and accessible English. Besides providing authoritative accounts of the key moments and dominant themes of his poetic development, the Companion examines his language, style and formal innovation, his prose and critical writing and his ideas about sexuality, religion, psychoanalysis, politics, landscape, ecology and globalisation. It also contains a comprehensive bibliography of writings about Auden. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO W. H. AUDEN EDITED BY STAN SMITH © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge -

W. H.AUDEN the DYER's

I I By W. H. Auden w. H.AUDEN ~ POEMS ANOTHER TIME THE DOUBLE MAN ON THIS ISLAND THE JOURNEY TO A WAR (with Christopher Isherwood) ASCENT OF F-6 (with Christopher Isherwood) DYER'S ON THE FRONTIER " (with Christopher Isherwood) LETTERS FROM ICELAND (with Louis MacNeice) HAND FOR THE TIME BEING THE SELECTED POETRY OF W. H. AUDEN (Modern Library) and other essays THE AGE OF ANXIETY NONES THE ENCHAFED FLOOD THE MAGIC FLUTE (with Chester Kallman) THE SHIELD OF ACHILLES HOMAGE TO CLIO THE DYER'S HAND Random House · New York ' I / ",/ \ I I" ; , ,/ !! , ./ < I The author wishes to thank the following for permission to reprint 1I1ateriar indilded in these essays: HARCOURT, BRACE & WORLD-and JONATHAN CAPE LTD. for selection from "Chard Whitlow" from A Map of Verona and Other Poems by Henry Reed. HARVARD UNIVERSITY PREss-and BASIL BLACKWELL & MOTT LTD. for selection from The Discovery of the Mind by Bruno SnelL HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON, INc.-for selections from Complete r Poems of Rohert Frost. Copyright 1916, 1921, 1923, 1928, 1930, 1939, 1947, 1949, by Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. FIRST PRINTING Copyright, 1948, 1950, 1952, 1953, 1954, © 1956, 1957, 1958, 1960, 1962, ALFRED A. KNOPF, INc.-for selections from The Borzoi Book of by W. H. Auden French Folk Tales, edited by Paul Delarue. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright THE MACMILLAN COMPANy-for selections from Collected Poems of Conventions. Published in New York by Random House, Inc., and simul Marianr.e Moore. Copyright 1935, 1941, 1951 by Marianne Moore; taneously in Toronto, Canada, by Random House of Canada, Limited. -

Auden at Work / Edited by Bonnie Costello, Rachel Galvin

Copyrighted material – 978–1–137–45292–4 Introduction, selection and editorial matter © Bonnie Costello and Rachel Galvin 2015 Individual chapters © Contributors 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–1–137–45292–4 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

Auden's Revisions

Auden’s Revisions By W. D. Quesenbery for Marilyn and in memoriam William York Tindall Grellet Collins Simpson © 2008, William D. Quesenbery Acknowledgments Were I to list everyone (and their affiliations) to whom I owe a debt of gratitude for their help in preparing this study, the list would be so long that no one would bother reading it. Literally, scores of reference librarians in the eastern United States and several dozen more in the United Kingdom stopped what they were doing, searched out a crumbling periodical from the stacks, made a Xerox copy and sent it along to me. I cannot thank them enough. Instead of that interminable list, I restrict myself to a handful of friends and colleagues who were instrumental in the publication of this book. First and foremost, Edward Mendelson, without whose encouragement this work would be moldering in Columbia University’s stacks; Gerald M. Pinciss, friend, colleague and cheer-leader of fifty-odd years standing, who gave up some of his own research time in England to seek out obscure citations; Robert Mohr, then a physics student at Swarthmore College, tracked down citations from 1966 forward when no English literature student stepped forward; Ken Prager and Whitney Quesenbery, computer experts who helped me with technical problems and many times saved this file from disappearing into cyberspace;. Emily Prager, who compiled the Index of First Lines and Titles. Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Table of Contents 4 General Introduction 7 Using the Appendices 14 PART I. PAID ON BOTH SIDES (1928) 17 Appendix 19 PART II. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19657-4 - W. H. Auden in Context Edited by Tony Sharpe Index More information Index Acton, Harold, 91 ‘As It Seemed to Us’, 14 ‘The Acts of John’, 86 ‘At the Grave of Henry James’, 75, 131, 375 The Adelphi, 338, 345 ‘Atlantis’, 50, 130 Agee, James, 215 ‘Aubade’, 348 Alexander, Michael, 260 ‘Auden and MacNeice: Their Last Will and Allen, Bill, 147 Testament’, 83, 241 Allen, John, 223, 225 ‘August for the people and their favourite Alston Moor, 15, 16 islands’, 41, 43, 212, 317 Alvarez, A. A., 365 ‘Balaam and his Ass’, 308 Amsterdam, 316 Berlin journals (unpublished), 24, 26, 317, Anders als die Andern, 103 355 Anglo-Saxon Reader (Sweet), 261 ‘Brothers and Others’, 272, 273 Ansen, Alan, 83, 91, 103, 121, 295n, 369, 378 ‘Bucolics’, 59, 64, 77, 178 Arendt, Hannah, 107, 126 ‘California’, 52 Aristotle, 181 ‘Case Histories’, 345 Arnold, Matthew, 49 ‘Christmas 1940’, 63 Ashbery, John, 124, 355 ‘Commentary’, 155, 157, 185 Astor, Lady Nancy, 146 ‘Consider this and in our time’, 2, 38, 153, Atlantic, 125 205–6 Auden, Constance, 69, 107 ‘Control of the passes was, he saw, the key’ Auden, George, 151, 259 (‘The Secret Agent’), 16, 20, 287, 361 Auden, John, 15, 45, 84, 86, 236 ‘Dame Kind’, 108 Auden’s writings ‘Deftly, admiral, cast your fly’, 334, 363 ‘1929’, 299, 362 ‘Dichtung und Wahrheit’, 183, 308, 363, 365 ‘A Bride in the ‘30s’, 376 ‘Dover’, 342–4 A Certain World, 19, 77, 87, 260, 329 ‘Easily, my dear,. .’, 207–8, 213 A Choice of de la Mare’s Verse, 360 Elegy for Young Lovers, 250, 324 ‘A Communist to Others’, -

What Kind of Guy? Michael Wood

8/14/2015 Michael Wood reviews ‘Later Auden’ by Edward Mendelson · LRB 10 June 1999 Back to article page What Kind of Guy? Michael Wood Later Auden by Edward Mendelson Faber, 570 pp, £25.00, May 1999, ISBN 0 571 19784 1 ‘That is the way things happen,’ Auden writes in ‘Memorial for the City’, a poem Edward Mendelson dates from June 1949, for ever and ever Plumblossom falls on the dead, the roar of the waterfall covers The cries of the whipped and the sighs of the lovers And the hard bright light composes A meaningless moment into an eternal fact Which a whistling messenger disappears with into a defile: One enjoys glory, one endures shame; He may, she must. There is no one to blame. Except that this is not the way things happen, only the way we have been taught to see them, by epic poets and the news camera. ‘Our grief is not Greek,’ Auden adds, meaning that the story of our time is not helpless pain and pity, however noble, not the repetitive horror of http://www.lrb.co.uk.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/v21/n12/michaelwood/whatkindofguy 1/12 8/14/2015 Michael Wood reviews ‘Later Auden’ by Edward Mendelson · LRB 10 June 1999 fame or disgrace or death without meaning on an indifferent earth. As we bury our dead We know without knowing there is reason for what we bear. We should probably add straightaway that the ancient Greeks also knew this, even if their reasons were different, so their grief wasn’t Greek in this sense either, but Auden’s point remains, a postHolocaust secularisation of T.S. -

Wystan Hugh) Auden

W. H. (Wystan Hugh) Auden: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Auden, W. H. (Wystan Hugh), 1907-1973 Title: W. H. (Wystan Hugh) Auden Collection Dates: 1929-1976, undated Extent: 5 boxes, 1 oversize box (3.76 linear feet), 2 oversize folders Abstract: Includes manuscripts and correspondence by the Anglo-American poet W. H. Auden, including libretti written in collaboration with his partner Chester Kallman, as well as other works and letters by Kallman. Additional correspondents include Don Bachardy, John Gardner, James Merrill, Nicolas Nabokov, Charles Osborne, Stephen Spender, and others. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-0152 Language: English, German, Greek, and Italian Access: Open for research Administrative Information Processed by: Joan Sibley and Katherine Noble, 2012 Note: This finding aid replicates and replaces information previously available only in a card catalog. Please see the explanatory note at the end of this finding aid for information regarding the arrangement of the manuscripts as well as the abbreviations commonly used in descriptions. Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Auden, W. H. (Wystan Hugh), 1907-1973 Manuscript Collection MS-0152 2 Auden, W. H. (Wystan Hugh), 1907-1973 Manuscript Collection MS-0152 Works: Container Unidentified dialogue, handwritten manuscript/ fragment, 1 page, undated. 1.1 Untitled poem, On the frontier at dawn… handwritten manuscript, 1 page, July no year (Zagreb). Written with this: four additional untitled poems (No trenchant parting this…; Truly our fathers had the gout…; We, knowing the family history…; Suppose they met, the inevitable procedure…) and The watershed; AN to Cecil Day-Lewis, undated.