Boethius and the Consolation of the Quadrivium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 59 In Memory of Christina Elliott Sorum 1944-2005 Copyright © 2005 American Council of Learned Societies Contents Introduction iii Pauline Yu Prologue 1 The Liberal Arts College: Identity, Variety, Destiny Francis Oakley I. The Past 15 The Liberal Arts Mission in Historical Context 15 Balancing Hopes and Limits in the Liberal Arts College 16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz The Problem of Mission: A Brief Survey of the Changing 26 Mission of the Liberal Arts Christina Elliott Sorum Response 40 Stephen Fix II. The Present 47 Economic Pressures 49 The Economic Challenges of Liberal Arts Colleges 50 Lucie Lapovsky Discounts and Spending at the Leading Liberal Arts Colleges 70 Roger T. Kaufman Response 80 Michael S. McPherson Teaching, Research, and Professional Life 87 Scholars and Teachers Revisited: In Continued Defense 88 of College Faculty Who Publish Robert A. McCaughey Beyond the Circle: Challenges and Opportunities 98 for the Contemporary Liberal Arts Teacher-Scholar Kimberly Benston Response 113 Kenneth P. Ruscio iii Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education II. The Present (cont'd) Educational Goals and Student Achievement 121 Built To Engage: Liberal Arts Colleges and 122 Effective Educational Practice George D. Kuh Selective and Non-Selective Alike: An Argument 151 for the Superior Educational Effectiveness of Smaller Liberal Arts Colleges Richard Ekman Response 172 Mitchell J. Chang III. The Future 177 Five Presidents on the Challenges Lying Ahead The Challenges Facing Public Liberal Arts Colleges 178 Mary K. Grant The Importance of Institutional Culture 188 Stephen R. -

Summer Professional Development for Classical Liberal Arts Teachers

Academy for Classical Teachers Summer Professional Development for Classical Liberal Arts Teachers 2020 Academy for Classical Teachers The Academy for Classical Teachers partners with the Institute for Classi- cal Education to offer online seminars and courses within the classical lib- eral arts tradition. If you are a certified teacher, course hours may be applicable toward re- quired professional development clock hours for recertification. ACT Summer Courses Online Seminars Plato’s Republic (June and July Offerings) Homer’s Iliad (July) Online Courses: Philosophy of Education: Classical Sources Symposium Follow Up: Thucydides’ Education in Virtuous Leadership The Enigma of Health: Natural Science and the Ensouled Body Quadrivium: Euclidean Geometry Questions? Reach out to [email protected] GreatHearts 4801 E. Washington Street, Suite 250 Phoenix, AZ 85034 www.greatheartsamerica.org Academy for Classical Teachers | 2020 Online Seminars Each year, the Academy for Classical Teachers offers leisurely summer seminars around classic philosophical and literary texts. This year, we are pleased to present online seminars on both Plato’s Republic and Homer’s Iliad. Cost: $125 Course Details Plato's Republic (June and July Offerings) June Seminar Plato’s Republic is without question one of the most important and influential books ever written, and it is difficult to understand Western civilization without engaging with The Re- June 8-26 public. It is beautifully written, very accessible, and it is a joy to read and discuss this book. Tues. & Thurs. This summer, members of the community will have a special opportunity for an in-depth 6 - 7:30 pm (CST) complete reading and 3-week series of Socratic seminar discussions on this seminal book. -

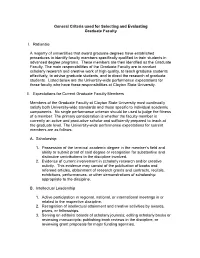

General Criteria Used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I

General Criteria used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I. Rationale A majority of universities that award graduate degrees have established procedures to identify faculty members specifically qualified to train students in advanced degree programs. These members are then identified as the Graduate Faculty. The main responsibilities of the Graduate Faculty are to conduct scholarly research and creative work of high quality, to teach graduate students effectively, to advise graduate students, and to direct the research of graduate students. Listed below are the University-wide performance expectations for those faculty who have these responsibilities at Clayton State University. II. Expectations for Current Graduate Faculty Members Members of the Graduate Faculty at Clayton State University must continually satisfy both University-wide standards and those specific to individual academic components. No single performance criterion should be used to judge the fitness of a member. The primary consideration is whether the faculty member is currently an active and productive scholar and sufficiently prepared to teach at the graduate level. The University-wide performance expectations for current members are as follows: A. Scholarship 1. Possession of the terminal academic degree in the member’s field and ability to submit proof of said degree or recognition for substantive and distinctive contributions to the discipline involved. 2. Evidence of current involvement in scholarly research and/or creative activity. This evidence may consist of the publication of books and refereed articles, obtainment of research grants and contracts, recitals, exhibitions, performances, or other demonstrations of scholarship appropriate to the discipline. B. Intellectual Leadership 1. Active participation in regional, national, or international meetings in or related to the respective discipline. -

Plato As "Architectof Science"

Plato as "Architectof Science" LEONID ZHMUD ABSTRACT The figureof the cordialhost of the Academy,who invitedthe mostgifted math- ematiciansand cultivatedpure research, whose keen intellectwas able if not to solve the particularproblem then at least to show the methodfor its solution: this figureis quite familiarto studentsof Greekscience. But was the Academy as such a centerof scientificresearch, and did Plato really set for mathemati- cians and astronomersthe problemsthey shouldstudy and methodsthey should use? Oursources tell aboutPlato's friendship or at leastacquaintance with many brilliantmathematicians of his day (Theodorus,Archytas, Theaetetus), but they were neverhis pupils,rather vice versa- he learnedmuch from them and actively used this knowledgein developinghis philosophy.There is no reliableevidence that Eudoxus,Menaechmus, Dinostratus, Theudius, and others, whom many scholarsunite into the groupof so-called"Academic mathematicians," ever were his pupilsor close associates.Our analysis of therelevant passages (Eratosthenes' Platonicus, Sosigenes ap. Simplicius, Proclus' Catalogue of geometers, and Philodemus'History of the Academy,etc.) shows thatthe very tendencyof por- trayingPlato as the architectof sciencegoes back to the earlyAcademy and is bornout of interpretationsof his dialogues. I Plato's relationship to the exact sciences used to be one of the traditional problems in the history of ancient Greek science and philosophy.' From the nineteenth century on it was examined in various aspects, the most significant of which were the historical, philosophical and methodological. In the last century and at the beginning of this century attention was paid peredominantly, although not exclusively, to the first of these aspects, especially to the questions how great Plato's contribution to specific math- ematical research really was, and how reliable our sources are in ascrib- ing to him particular scientific discoveries. -

Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology

VIEWPOINT Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology: Time for Another Renewal Liberal arts colleges must accommodate the powerful changes that are taking place in the way people communicate and learn by Todd D. Kelley hree significant societal trends and that institutional planning and deci- Five principal reasons why the future will most certainly have a broad sion making must reflect the realities of success of liberal arts colleges is tied to Timpact on information services rapidly changing information technol- their effective use of information tech- and higher education for some time to ogy. Boards of trustees and senior man- nology are: come: agement must not delay in examining • Liberal arts colleges have an obliga- • the increasing use of information how these changes in society will impact tion to prepare their students for life- technology (IT) for worldwide com- their institutions, both negatively and long learning and for the leadership munications and information cre- positively, and in embracing the idea roles they will assume when they ation, storage, and retrieval; that IT is integral to fulfilling their liberal graduate. • the continuing rapid change in the arts missions in the future. • Liberal arts colleges must demon- development, maturity, and uses of (2) To plan and support technological strate the use of the most significant information technology itself; and change effectively, their colleges must approaches to problem solving and • the growing need in society for have sufficient high-quality information communications to have emerged skilled workers who can understand services staff and must take a flexible and since the invention of the printing and take advantage of the new meth- creative approach to recruiting and press and movable type. -

Chapter Two Democritus and the Different Limits to Divisibility

CHAPTER TWO DEMOCRITUS AND THE DIFFERENT LIMITS TO DIVISIBILITY § 0. Introduction In the previous chapter I tried to give an extensive analysis of the reasoning in and behind the first arguments in the history of philosophy in which problems of continuity and infinite divisibility emerged. The impact of these arguments must have been enormous. Designed to show that rationally speaking one was better off with an Eleatic universe without plurality and without motion, Zeno’s paradoxes were a challenge to everyone who wanted to salvage at least those two basic features of the world of common sense. On the other hand, sceptics, for whatever reason weary of common sense, could employ Zeno-style arguments to keep up the pressure. The most notable representative of the latter group is Gorgias, who in his book On not-being or On nature referred to ‘Zeno’s argument’, presumably in a demonstration that what is without body and does not have parts, is not. It is possible that this followed an earlier argument of his that whatever is one, must be without body.1 We recognize here what Aristotle calls Zeno’s principle, that what does not have bulk or size, is not. Also in the following we meet familiar Zenonian themes: Further, if it moves and shifts [as] one, what is, is divided, not being continuous, and there [it is] not something. Hence, if it moves everywhere, it is divided everywhere. But if that is the case, then everywhere it is not. For it is there deprived of being, he says, where it is divided, instead of ‘void’ using ‘being divided’.2 Gorgias is talking here about the situation that there is motion within what is. -

The Pythagoreans in the Light and Shadows of Recent Research

The Pythagoreans in the light and shadows of recent research PAPER PRESENTED AT THE DONNERIAN SYMPOSIUM ON MYSTICISM, SEPTEMBER 7th 1968 By HOLGER THESLEFF It has been said' that "Pythagoras casts a long shadow in the history of Greek thought". Indeed, the shadow both widens and deepens spectacularly in course of time. He has not only been considered—on disputable grounds, as we shall see as the first European mystic. No other personality of the Greco–Roman world (except Christ, and perhaps Alexander the Great) has been credited with such powers and all-round capacities. Since early Impe- rial times he has been represented as a man of divine origin, a saint, a sage, a prophet, and a great magician; a sportsman and an ascetic; a poet and prose- writer; a Dorian nationalist (though an Ionian by birth); an eminent mathe- matician, musician, astronomer, logician, rhetorician, and physician; a world-wide traveller; a founder of a religious sect, an ethical brotherhood, and a political community; a great metaphysician and teacher whose views of the universe, human society and the human soul deeply influenced not only Plato and Aristotle, but Herakleitos, Parmenides, Demokritos and, in short, all prominent thinkers; a preacher of universal tolerance, and—a good hus- band and father. There can be seen occasional signs of a revival of Pythagoreanism at least from the ist century A. D. onwards,2 and some authors of the Imperial age 1 Philip (below), p. 3. 2 If Pseudo-Pythagorica are left out of account, the activity of the Sextii in Rome during the reign of Augustus is the first manifest sign. -

The Magisterium of the Faculty of Theology of Paris in the Seventeenth Century

Theological Studies 53 (1992) THE MAGISTERIUM OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF PARIS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JACQUES M. GRES-GAYER Catholic University of America S THEOLOGIANS know well, the term "magisterium" denotes the ex A ercise of teaching authority in the Catholic Church.1 The transfer of this teaching authority from those who had acquired knowledge to those who received power2 was a long, gradual, and complicated pro cess, the history of which has only partially been written. Some sig nificant elements of this history have been overlooked, impairing a full appreciation of one of the most significant semantic shifts in Catholic ecclesiology. One might well ascribe this mutation to the impetus of the Triden tine renewal and the "second Roman centralization" it fostered.3 It would be simplistic, however, to assume that this desire by the hier archy to control better the exposition of doctrine4 was never chal lenged. There were serious resistances that reveal the complexity of the issue, as the case of the Faculty of Theology of Paris during the seventeenth century abundantly shows. 1 F. A. Sullivan, Magisterium (New York: Paulist, 1983) 181-83. 2 Y. Congar, 'Tour une histoire sémantique du terme Magisterium/ Revue des Sci ences philosophiques et théologiques 60 (1976) 85-98; "Bref historique des formes du 'Magistère' et de ses relations avec les docteurs," RSPhTh 60 (1976) 99-112 (also in Droit ancien et structures ecclésiales [London: Variorum Reprints, 1982]; English trans, in Readings in Moral Theology 3: The Magisterium and Morality [New York: Paulist, 1982] 314-31). In Magisterium and Theologians: Historical Perspectives (Chicago Stud ies 17 [1978]), see the remarks of Y. -

OAKWOOD UNIVERSITY Faculty Handbook

FACULTY HANDBOOK OAKWOOD UNIVERSITY Faculty Handbook (Revised 2008) Faculty Handbook Page 1 FACULTY HANDBOOK Table of Contents Section I General Administration Information Oakwood University Mission Statement ........................................................................................... 5 Historic Glimpses .............................................................................................................................. 5 Accreditation ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Affirmative Action and Religious Institution Exemption .................................................................. 6 Sexual Harassment ............................................................................................................................. 6 Drug-free Environment ...................................................................................................................... 7 Establishment and Dissolution of Departments and Majors .............................................................. 8 Section II Policies Governing Faculty Functions Faculty Classifications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Academic Rank ................................................................................................................................. 11 Promotions ....................................................................................................................................... -

Notes: Definition and Explanation of Trivium and Quadrivium

DEFINITION AND EXPLANATION OF TRIVIUM AND QUADRIVIUM (From the first time I taught the course--my notes) (Communication Education, Vol. 35,#2, April, 1986, 174, Teaching Critical Thinking Skills) In the Middle Ages university courses were divided into two areas, the Arts and the Sciences. These were a system of rules for generating knowledge. The seven Liberal Arts of Languages ( or Arts) and Sciences were complements, and obviously comprised a Liberal Arts education .. TRIVIUM The Languages (ARTS), or Trivium were composed of: Grammar (Latin) Logic Rhetoric These Arts were concerned with (and were to discover) the social significance of knowledge. These Arts were relatively subjective. Completion of this study led to a bachelor's degree. QUADRIVIUM The Sciences, the Quadrivium, was composed of: Arithmetic Geometry Astronomy Music The Sciences arranged knowledge into systematic bodies of information. The Sciences were relatively objective. Completion of the Quadrivium led to a master's degree (Continued Explanation of Trivium and Quadrivium) Rhetoric, chief among the courses of the Trivium, liberated students from a single view of a problem and led them to social autonomy. The divisions of classical rhetoric provide directions forteaching critical thinking skills. Peter Ramus, 1515-1572, redefined ancient discipliines: Beginning with the trivium, with the arts of discourse, Ramus defined grammar as the art of speaking well, that is of speaking correctly; dialectic as the art of reasoning well; and rhetoric as the art of the eloquent and ornate use of language. Skills arising from Invention/inventio/heuristic were insights from researched information and discovery of arguments to support the point of view espoused. -

Spring 2016 Volume 42 Issue 3

Spring 2016 Volume 42 Issue 3 341 David Foster Holbein and Plato on the Quadrivium 367 Nelson Lund A Woman’s Laws and a Man’s: Eros and Thumos in Rousseau’s Julie, or The New Heloise (1761) and The Deer Hunter (1978) 437 Thomas L. Pangle Socrates’s Argument for the Superiority of the Life Dedicated to Politics Review Essays: 463 Liu Xiaofeng How Philosophy Became Socratic: A Study of Plato’s “Protagoras,” “Charmides,” and “Republic” by Laurence Lampert 477 Matthew Post The Meanings of Rights: The Philosophy and Social Theory of Rights, ed. Costas Douzinas and Conor Gearty; Libertarian Philosophy in the Real World: The Politics of Natural Rights by Mark D. Friedman; The Cambridge Companion to Liberalism by Steven Wall An Exchange: 495 Tucker Landy Reply to Antoine Pageau St.-Hilaire’s Review of After Leo Strauss: New Directions in Platonic Political Philosophy 497 Antoine P. St-Hilaire Strauss’s Platonism and the Fate of Metaphysics: A Rejoinder to Tucker Landy’s Reply Book Reviews: 501 Rodrigo Chacón Arendtian Constitutionalism: Law, Politics and the Order of Freedom by Christian Volk 507 Ross J. Corbett Scripture and Law in the Dead Sea Scrolls by Alex P. Jassen 513 Bernard J. Dobski On Sovereignty and other Political Delusions by Joan Cocks; Freedom Beyond Sovereignty: Reconstructing Liberal Individualism by Sharon Krause 521 Lewis Fallis On Plato’s “Euthyphro” by Ronna Burger 525 Hannes Kerber Political Philosophy: What It Is and Why It Matters by Ronald Beiner 531 Pavlos Leonidas Western Civilization and the Academy by Bradley C. S. Watson Papadopoulos 543 Antonio Sosa Democracy in Decline? by Larry Diamond and Marc F. -

Proclus and Artemis: on the Relevance of Neoplatonism to the Modern Study of Ancient Religion

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 13 | 2000 Varia Proclus and Artemis: On the Relevance of Neoplatonism to the Modern Study of Ancient Religion Spyridon Rangos Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/1293 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.1293 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2000 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Spyridon Rangos, « Proclus and Artemis: On the Relevance of Neoplatonism to the Modern Study of Ancient Religion », Kernos [Online], 13 | 2000, Online since 21 April 2011, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/1293 ; DOI : 10.4000/kernos.1293 Kernos Kernos, 13 (2000), p. 47-84. Proclus and Artemis: On the Relevance of Neoplatonism to the Modern Study of Andent Religion* Imagine the situation in which contemporary philosophers would find themselves if Wittgenstein introduced, in his Philosophical Investigations, the religious figure of Jesus as Logos and Son of God in order to illuminate the puzzlement ofthe private-language paradox, or if in the second division of Being and Time Heidegger mentioned the archangel Michael to support the argument of 'being toward death'. Similar is the perplexity that a modern reader is bound to encounter when, after a highly sophisticated analysis of demanding metaphysical questions about the relationship of the one and the many, finitude and infinity, mind and body, Proclus, l in ail seriousness and without the slightest touch of irony, assigns to some traditional gods of Greek polytheism a definitive place in the structure of being.