Melissa Aldana Wins 2013 Monk Sax Comp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brochure1516.Pdf

Da Camera 15-16 Season Brochure.indd 1 3/26/15 4:05 PM AT A SARAH ROTHENBERG SEASONGLANCE artistic & general director SEASON OPENING NIGHT ő Dear Friends of Da Camera, SNAPSHOTS OF AMERICA SARAH ROTHENBERG: Music has the power to inspire, to entertain, to provoke, to fire the imagination. DAWN UPSHAW, SOPRANO; THE MARCEL PROUST PROJECT It can also evoke time and place. With Snapshots: Time and Place, Da Camera GILBERT KALISH, PIANO; WITH NICHOLAS PHAN, TENOR Sō PERCUSSION AND SPECIAL GUESTS Thursday, February 11, 2016, 8:00 PM takes the work of pivotal musical figures as the lens through which to see a Saturday, September 26, 2015; 8:00 PM Friday, February 12, 2016, 8:00 PM decade. Traversing diverse musical styles and over 600 years of human history, Cullen Theater, Wortham Theater Center Cullen Theater, Wortham Theater Center the concerts and multimedia performances of our 2015/16 season offer unique perspectives on our past and our present world. ROMANTIC TITANS: BRENTANO QUARTET: BEETHOVEN SYMPHONY NO. 5 AND LISZT THE QUARTET AS AUTOBIOGRAPHY Our all-star Opening Night, Snapshots of America, captures the essence of the YURY MARTYNOV, PIANO Tuesday, February 23, 2016, 7:30 PM American spirit and features world-renowned soprano Dawn Upshaw. Paris, city Tuesday, October 13, 2015, 7:30 PM The Menil Collection of light, returns to the Da Camera stage in a new multi-media production The Menil Collection GUILLERMO KLEIN Y LOS GUACHOS inspired by the writings of Marcel Proust. ARTURO O'FARRILL Saturday, March 19, 2016, 8:00 PM Two fascinating -

Download 2018 Catalog

JUNE 23 Bing Concert Hall Joshua Redman Quartet presented by JUNE 22 – AUGUST 4 28 BRILLIANT CONCERTS STANFORDJAZZ.ORG presented by JUNE JULY FRI FRI FRI FRI SAT SAT SAT SAT SAT MON SUN SUN 22 23 SUN 24 29 30 1 6 7 7 13 14 15 16 Indian Jazz Journey JUNE 22 – AUGUST 4 with Jazz on 28 BRILLIANT CONCERTS George the Green: Brooks, Early Bird Miles STANFORDJAZZ.ORG Jazz featuring Jazz for Electric Ruth Davies’ Inside Out Mahesh Dick Kids: An Band, Kev Tommy Somethin’ Blues Night with Joshua Kale and Tiffany Christian Hyman Jim Nadel American Choice, Igoe and Else: A with Special Jim Nadel Redman Bickram Austin McBride’s and Ken and the Songbook Sidewalk the Art of Tribute to Guest Eric & Friends Quartet Ghosh Septet New Jawn Or Bareket Peplowski Zookeepers Celebration Chalk Jazz Cannonball Bibb JULY AUGUST FRI FRI SAT SAT SAT TUE WED THU THU SUN SUN WED WED MON 18 19 21 22 23 25 26 27 28 29 MON 30 31 1 3 4 SJW All-Star Jam Wycliffe Gordon, Melissa Aldana, Taylor Eigsti, Yosvany Terry, Charles McPherson, Jeb Patton, Tupac SJW CD Mantilla, Release Jazz Brazil: Dena Camila SJW CD Regina Party: Anat DeRose Jeb Patton Meza, Release Carter Caroline Cohen/ Terrence Trio with Trio and Yotam party: An & Xavier Davis’ Romero Brewer Anat Yosvany Tupac Silberstein, Debbie Evening Davis: Heart Tonic Lubambo/ Acoustic Cohen and Charles Terry Taylor Mantilla’s Mike Andrea Poryes/ with Duos and Bria and Jessica Vitor Remembering Jazz Jimmy McPherson Afro-Cuban Eigsti Trio Point of Rodriguez, Motis Sam Reider Victor Lin Quartet Skonberg Jones Gonçalves Ndugu Quartet Heath Quintet Sextet and Friends View and others. -

TKA APAP Brochure 20

2017 - 2018 SQUIRREL NUT ZIPPERS DAVINA and the VAGABONDS Table of Contents Afro-Cuban All Stars 1 Ann Hampton Callaway 2 Arturo Sandoval 3 Béla Fleck 4 Bettye LaVette 5 Agents Bill Charlap 6 Brian Blade & The Fellowship Band 7 Catherine Russell 8 Cécile McLorin Salvant 9 Agents Charles Lloyd 10 Chick Corea 11 Jack Randall - [email protected] Davina & The Vagabonds 12 AK, AZ, CA, HI, IL, IA, MI, MN, NE, NV, OR, WA, WI, & CANADA Eileen Ivers 13 Ellis Marsalis 14 Jamie Ziefert - [email protected] Elvin Bishop 15 CT, DE, ME, MD, MA, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT, VA, WV, & D.C. Harold López-Nussa 16 Herlin Riley 17 Dan Peraino - [email protected] Hot Club of Cowtown 18 AL, AR, CO, FL, GA, KY, ID, IN, KS, LA, MS, MO, MT, NC, ND, NM, Jack Broadbent 19 OH, OK, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, WY, PR, & US VIRGIN ISLANDS James Cotton 20 Jamison Ross 21 Gunter Schroder - [email protected] JLCO with Wynton Marsalis 22 EUROPE, NORTH AFRICA, SOUTH AFRICA, MIDDLE EAST Joey Alexander 23 Joey DeFrancesco 24 Matt McCluskey - [email protected] John Pizzarelli 25 ASIA/PACIFIC, AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND, John Sebastian 26 LATIN/SOUTH AMERICA, CARIBBEAN Lisa Fischer 27 Marcia Ball 28 Ted Kurland - [email protected] Melissa Aldana 29 PRESIDENT Meshell Ndegeocello 30 Pat Metheny 31 Ravi Coltrane 32 Red Baraat 33 Savion Glover 34 APAP BOOTH #1003 Sonny Knight and The Lakers 35 Soul Rebels 36 Squirrel Nut Zippers 37 Stacey Kent 38 The Kurland Agency 173 Brighton Avenue Boston, MA 02134 p | (617) 254-0007 e | [email protected] www.thekurlandagency.com AFRO-CUBAN ALL STARS Juan de Marcos González, founder of Sierra Maestra and AFRO-CUBAN ALL STARS and one of the key creators of the Buena Vista Social Club, began his career paying tribute to the traditional Cuban music of the 1950’s, considered the golden age of Cuban music. -

2020Virtualfestivalpartnershipd

THREE DAYS IN SUPPORT OF THREE NONPROFITS • The NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF) is America’s premier legal organization fighting for racial justice. Through litigation, advocacy, and public education, LDF seeks structural changes to expand democracy, eliminate disparities, and achieve racial justice in a society that fulfills the promise of equality for all Americans. LDF is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization • The Thurgood Marshall College Fund (TMCF) is the nation’s largest nonprofit organization exclusively representing the Black College Community. TMCF member-schools include the publicly-supported Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and Predominantly Black Institutions (PBIs). • The Monterey Jazz Festival is the oldest continuously-running jazz festival in the world established as a nonprofit organization in 1958. MJF will support participating jazz artists who are disproportionately impacted and losing their livelihoods due to COVID-19. The Monterey Jazz Festival’s mission is to inspire the discovery and celebration of jazz, anchored by an iconic festival. Even though we are not able to host an in-person festival in 2020, our work is anchored by an annual communion around jazz, a music rooted in black culture. A Virtual Festival in 2020 allows us to: • support our community of jazz musicians who have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19; • celebrate student musicians who have lost so many celebratory moments in 2020, such as proms and graduations; • take action to support trusted nonprofit organizations doing important work to promote social justice, end racism, provide equal opportunity and celebrate black culture. Black Lives Matter! Title Partnership Opportunity MJF Partnership $100,000 level includes 2 Years of benefits! • Designation as the Presenting Sponsor of the 2020 Virtual Monterey Jazz Festival benefiting THREE trusted nonprofit organizations playing critical roles in solving racial injustice and inequality. -

Satoko Fujii in NYC Satokofujii.Com

power. The excitement stems from Aldana’s Never Be Another You” and melting tone on “The precociously mature lyric intelligence wedded to a Nearness Of You”. Worthy of mention, too, is di sensitive but restrained romanticism. The pared-down Martino’s lightly swinging work on “Moonglow” and format of her Crash Trio, with bassist Pablo Menares (a inspired pianistics on a bossa treatment of “Say It Isn’t fellow Chilean) and Cuban drummer Francisco Mela, So”. Other highlights are Kozlov’s arco introduction to gives her full freedom to explore, along with the “For All We Know” and Takahashi’s outstanding consequent responsibility to imply harmony in lieu of brushwork on “It Could Happen To You” and pulsing chording instruments. drumming on the Latin-ized “For All We Know”. The setlist contains two covers and tunes by each The ingredients in this album—a talented vocalist, Root of Things bandmember, mostly straightforward compositions five most able musicians and some of the best songs to Matthew Shipp Trio (Relative Pitch) with quirky twists, Mela’s catchy samba “Dear Joe” be found—all make for a most delicious treat. Enjoy! by Jeff Stockton probably the most memorable of the lot. But what jumps off the CD is the graceful, unbroken logic and For more information, visit barbaralevydaniels.com. Daniels Pianist Matthew Shipp is frequently labeled “cerebral” syntax of Aldana’s improvisations, a mix of extended is at Metropolitan Room Jun. 18th. See Calendar. and his playing is usually described using a math phrases and shorter exclamations, glued together with metaphor. Yet his musicianship with the David S. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

Readers Poll

84 READERS POLL DOWNBEAT HALL OF FAME One night in November 1955, a cooperative then known as The Jazz Messengers took the stage of New York’s Cafe Bohemia. Their performance would yield two albums (At The Cafe Bohemia, Volume 1 and Volume 2 on Blue Note) and help spark the rise of hard-bop. By Aaron Cohen t 25 years old, tenor saxophonist Hank Mobley should offer a crucial statement on how jazz was transformed during Aalready have been widely acclaimed for what he that decade. Dissonance, electronic experimentation and more brought to the ensemble: making tricky tempo chang- open-ended collective improvisation were not the only stylis- es sound easy, playing with a big, full sound on ballads and pen- tic advances that marked what became known as “The ’60s.” ning strong compositions. But when his name was introduced Mobley’s warm tone didn’t necessarily coincide with clichés on the first night at Cafe Bohemia, he received just a brief smat- of the tumultuous era, as the saxophonist purposefully placed tering of applause. That contrast between his incredible artistry himself beyond perceived trends. and an audience’s understated reaction encapsulates his career. That individualism came across in one of his rare inter- Critic Leonard Feather described Mobley as “the middle- views, which he gave to writer John Litweiler for “Hank Mobley: weight champion of the tenor saxophone.” Likely not intended The Integrity of the Artist–The Soul of the Man,” which ran in to be disrespectful, the phrase implied that his sound was some- the March 29, 1973, issue of DownBeat. -

Melissa Aldana Wins 2013 Thelonious Monk Competition

washingt o ncit ypaper.co m http://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/blogs/artsdesk/music/2013/09/17/melissa-aldana-wins-2013-thelonious-monk-competition Melissa Aldana Wins 2013 Thelonious Monk Competition Posted by Michael J. West on Sep. 17, 2013 at 11:30 am Jazz history was made at the Kennedy Center Monday night. In the 27-year history of jazz's most prestigious international competition, a woman has never won in the instrumental categories. (Conversely, only women have won the vocal competitions, raising discomf iting questions about women's "place" in the music.) That precedent was shattered in this year's Thelonious Monk International Saxophone Competition, when Melissa Aldana, a 24-year-old tenor saxophonist f rom Santiago, Chile, won the grand prize of a $25,000 scholarship and record contract with Concord Music Group. Better yet, she got to take a victory lap in a blowing session with f ellow saxophonists (and judges) Jimmy Heath, Bobby Watson, Jane Ira Bloom, Branford Marsalis, and Wayne Shorter, plus a kaleidoscope of other musicians, on Heath's classic "Gingerbread Boy." Aldana, who graduated f rom Boston's Berklee Conservatory and has lived in New York since 2009, is a legacy. Her f ather, Chilean saxophonist Marco Aldana, was a semif inalist in the 1991 Thelonious Monk Competition. She took f irst place on the strength of her two perf ormances: the 1930s standard "I Thought About You"— which she played in a bluesy, noirish mode—and the self -composed title track to her 2010 debut recording, Free Fall. Aldana played both tunes with considerable subtlety and a sof t touch on the keys, but also with caref ul attention to detail and, most distinctively, descending slurs that served as a musical signature. -

Melissa Aldana Wins Thelonious Monk Competition for Saxophonists

npr.o rg http://www.npr.org/blogs/ablogsupreme/2013/09/17/223433259/melissa-aldana-wins-thelonious-monk-competition-for- saxophonists Melissa Aldana Wins Thelonious Monk Competition For Saxophonists From NPR Jazz Enlarge image Paul Morigi/Getty Images f or the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz At a ceremony and concert last night in Washington, D.C., the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz named Melissa Aldana, 24, the winner of its annual competition f or young musicians. The highest- prof ile event of its kind, this year's competition was open to saxophonists. Aldana, who plays tenor sax, is the f irst f emale instrumentalist to take f irst prize in the event's history, held every year since 1987. She wins $25,000 in scholarship money and a recording contract with Concord Music Group. Fellow tenor player Tivon Pennicott, 27, won second prize and a $15,000 scholarship; alto saxophonist Godwin Louis, 28, f inished third and took home $10,000 in scholarship f unds. All three f inalists are currently based in New York City. "I'm really good f riends with Godwin and Tivon," Aldana said f ollowing the competition. "They are like my brothers, so I was really honored to be next to them." In the f inal round, she perf ormed a medium-slow take on the standard "I Thought About You," showcasing her dark tone, motivic development and creative ornamentation; she also called an original Me lissa Ald ana p e rfo rms at the 2013 The lo nio us Mo nk Inte rnatio nal Jazz Saxo p ho ne Co mp e titio n at The Jo hn F. -

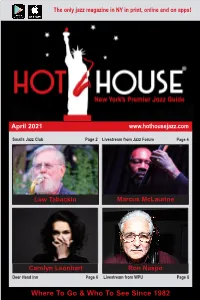

Where to Go & Who to See Since 1982

April Hot House 2021_Layout 1 3/24/2021 5:28 PM Page 1 The only jazz magazine in NY in print, online and on apps! April 2021 www.hothousejazz.com Smalls Jazz Club Page 2 Livestream from Jazz Forum Page 4 Lew Tabackin Marcus McLaurine Carolyn Leonhart Ron Naspo Deer Head Inn Page 6 Livestream from WPU Page 8 Where To Go & Who To See Since 1982 April Hot House 2021_Layout 1 3/24/2021 5:28 PM Page 2 Aging Like Fine Wine: derange it,” the jazzman muses. “I don’t like to just get up and play, I like to get inside the song, become one with the song. I try to internalize what I play until the LEW TABACKIN song is you: You feel like you wrote it. It becomes a part of you.” By Elzy Kolb Even better is when he can bring the lis- teners along with him. Lew recalls a night when “I landed on a note that was nothing special, in a way, but I put all of my com- municative energy into that note and felt the audience coming into it too. It was the ultimate Zen experience, the ultimate thing to aspire to: reaching the audience in a special, personal way. Not like playing something stupid and the audience goes crazy, but playing something simple and the audience becomes part of it. That does- n’t happen very often. It will be fun to see if I can still pull it off.” Lew’s performances since the start of the pandemic include just three livestreams, and a recent gig at the Deer Head Inn, placing him in front of people for the first time in more than a year. -

Monterey Jazz Festival on Tour

Monterey Jazz Festival on Tour featuring Cécile McLorin Salvant / Vocals Bria Skonberg / Trumpet Melissa Aldana / Tenor Saxophone Christian Sands / Piano and Music Director Yasushi Nakamura / Bass Jamison Ross / Drums Sunday Afternoon, April 14, 2019 at 4:00 Michigan Theater Ann Arbor 47th Performance of the 140th Annual Season 25th Annual Jazz Series This afternoon’s performance is supported by Louise Taylor. Funded in part by the JazzNet Endowment Fund. Media partnership provided by WEMU 89.1 FM, WRCJ 90.9 FM, WDET 101.9 FM, Ann Arbor’s 107one, and Metro Times. Special thanks to Brendan Asante, Seema Jolly, and the Ann Arbor Public Schools Community Education and Recreation (Rec & Ed) for their participation in events surrounding this afternoon’s performance. Monterey Jazz Festival on Tour appears by arrangement with The Kurland Agency. In consideration of the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. PROGRAM This afternoon’s program will be announced by the artists from the stage and is performed without intermission. 3 4 ARTISTS The Monterey Jazz Festival (MJF), the The Monterey Jazz Festival has longest continuously running jazz festival presented nearly every major jazz star — in the world, is pleased to present its from Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong fifth national tour this spring, featuring to Esperanza Spalding and Trombone some of the most critically acclaimed Shorty — since it was founded in 1958. Grammy-winning and Grammy-nominated Held every third full weekend in September jazz artists of their generation, including on the Monterey County Fairgrounds, the three winners of the Thelonious Monk Monterey Jazz Festival is a three-day International Jazz Competition. -

Visions for Frida Kahlo Melissa Aldana

MARCH 27 8 PM FRIDAY MEMORIAL HALL BEASLEY-CURTIS AUDITORIUM APPROXIMATELY 110 MINUTES, INCLUDING INTERMISSION VISIONS FOR FRIDA KAHLO MELISSA ALDANA MELISSA ALDANA, saxophone SAM HARRIS, piano PABLO MENARES, bass JIMMY MACBRIDE, drums MOTEMA MUSIC, animations PHOTO BY HARRISON WEINSTEIN STUDENT TICKET ANGEL FUND BENEFACTORS PAULA NOELL & PALMER PAGE 46 TICKET SERVICES 919.843.3333 “THIS WAS A PERFORMANCE SO FULL OF FRESHNESS AND POISE THAT, WATCHING IT, YOU COULD NOT HELP BUT BE CONVINCED YOU WERE WITNESSING A FUTURE STAR.” —JAZZWISE MAGAZINE BORN IN SANTIAGO, CHILE, In addition, Aldana has been awarded Melissa Aldana began playing the the Altazor National Arts Award of Chile saxophone at the age of six under the and the Lincoln Center’s Martin E. Segal influence and tutelage of her father, Award. She has played concerts alongside professional saxophonist Marcos Aldana. artists such as Peter Bernstein, Kevin Aldana began with alto, influenced by Hays, Christian McBride, and Jeff “Tain” artists such as Charlie Parker, Cannonball Watts, and many festivals including the Adderley, and Michael Brecker. However, Copenhagen Jazz Festival, Twin Cities Jazz after hearing the music of Sonny Rollins, Festival, and Providencia Jazz Festival she switched to tenor, first playing a in Chile. She also performed with Jimmy Selmer Mark VI model saxophone that had Heath at the 2014 NEA Jazz Masters belonged to her grandfather. Award Ceremony, and was invited to Jazz at Lincoln Center by Wynton Marsalis. “One of the most exciting tenor saxophonists today,” (New York Times) Aldana’s first performance with Carolina Aldana started performing in Santiago Performing Arts, Visions for Frida Kahlo jazz clubs in her early teens.