Modernity Crisis and Its Reflections in Tarkovsky's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

The Holy Fool in Late Tarkovsky

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha Journal of Religion & Film Volume 18 | Issue 1 Article 45 3-31-2014 The olH y Fool in Late Tarkovsky Robert O. Efird Virginia Tech, [email protected] Recommended Citation Efird, Robert O. (2014) "The oH ly Fool in Late Tarkovsky," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 18 : Iss. 1 , Article 45. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol18/iss1/45 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The olH y Fool in Late Tarkovsky Abstract This article analyzes the Russian cultural and religious phenomenon of holy foolishness (iurodstvo) in director Andrei Tarkovsky’s last two films, Nostalghia and Sacrifice. While traits of the holy fool appear in various characters throughout the director’s oeuvre, a marked change occurs in the films made outside the Soviet Union. Coincident with the films’ increasing disregard for spatiotemporal consistency and sharper eschatological focus, the character of the fool now appears to veer off into genuine insanity, albeit with a seemingly greater sensitivity to a visionary or virtual world of the spirit and explicit messianic task. Keywords Andrei Tarkovsky, Sacrifice, Nostalghia, Holy Foolishness Author Notes Robert Efird is Assistant Professor of Russian at Virginia Tech. He holds a PhD in Slavic from the University of Virginia and is the author of a number of articles dealing with Russian and Soviet cinema. -

CFP Refocus: the Films of Andrei Tarkovsky

H-Announce CFP ReFocus: The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky Announcement published by Sergei Toymentsev on Wednesday, August 3, 2016 Type: Call for Publications Date: November 30, 2016 Location: United States Subject Fields: Art, Art History & Visual Studies, Cultural History / Studies, Film and Film History, Humanities, Russian or Soviet History / Studies ReFocus: The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky Andrei Tarkovsky (1932 -1986) is a renowned Russian filmmaker whose work, despite an output of only seven feature films in twenty years, has had a profound influence on international cinema. Famous for languid pacing, long takes, dreamlike imagery, spiritual depth and philosophical allegories, most of his films have gained cult status among cineastes and are often included in various kinds of ranking polls and charts dedicated to the "best movies ever made." Thus, for example, the British Film Institute's "50 Greatest Films of All Time" poll conducted for the film magazine Sight & Sound in 2012 honors three of Tarkovsky's films: Andrei Rublev (1966) is ranked at No. 26, Mirror (1974) at No. 19, and Stalker (1979) at No. 29. Beginning with the late 1980, Tarkovsky's highly complex cinema has continuously attracted scholarly and critical attention in film studies by generating countless hermeneutic challenges and possibilities for film scholars. Almost all intellectual vogues and methodologies in humanities, whether it's feminism, psychoanalysis, poststructuralism, diaspora studies or film-philosophy, have left their interpretative trace on the reception of his work. This ReFocus anthology on Andrei Tarkovsky invites chapter proposals of 200-400 words that would take yet another look at the director's legacy from interdisciplinary perspectives. -

Full Cinematic Retrospective of Director Andrei Tarkovsky This Summer at MAD

Full Cinematic Retrospective of Director Andrei Tarkovsky this Summer at MAD Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time presents the work of the revolutionary director and includes screenings—all on 35 mm—of all seven feature films and a behind-the-scenes documentary Stalker, 1976. Andrei Tarkovsky. New York, NY (June 8, 2015)—The Museum of Arts and Design presents a full cinematic retrospective of Andrei Tarkovsky’s work this summer with its latest cinema series, Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, from July 10 through August 28, 2015. Over the course of just seven feature films, Tarkovsky produced a poetic and enigmatic body of work that expanded the possibilities of cinema as an art form and transformed a wide range of genres including science fiction, war stories, film essays and historical dramas. Celebrating the legacy of this revolutionary director, the retrospective includes screenings of Tarkovsky’s seven feature films on 35 mm, as well as a behind-the-scenes documentary that reveals the process behind his groundbreaking practice and cinematic achievements. “Few directors have had as large of an influence on cinema as Andrei Tarkovsky,” says Jake Yuzna, MAD’s Director of Public Programs. “Working under censorship and with little support from the Soviet Union, Tarkovsky fought fiercely for his conceptualization of cinema as a singular and vital art form. Reconsidering the role of films in an age of increasing technology, Tarkovsky saw cinema as not merely a tool for communicating information, but as ‘a moral barometer in a sea of competing narratives.’” 2 COLUMBUS CIRCLE NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 P 212.299.7777 F 212.299.7701 MADMUSEUM.ORG Premiering on July 10 with Tarkovsky’s science fiction classic, Solaris, the retrospective showcases the director’s distinctive and influential aesthetic, characterized by expressive, sweeping takes, the evocative use of landscapes, and his method of “sculpting in time” with a camera. -

Russian Cinema Now, an 11-Film Showcase of Contemporary Films, May 31— Jun 13

BAMcinématek presents the 30th anniversary of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia for two weeks in a new 35mm print, alongside Russian Cinema Now, an 11-film showcase of contemporary films, May 31— Jun 13 In association with TransCultural Express: American and Russian Arts Today, a partnership with the Mikhail Prokhorov Fund to promote cultural exchange between American and Russian artists and audiences Three North American premieres, three US premieres, and special guests including legendary Fugees producer John Forté and friends and acclaimed directors Sergei Loznitsa and Andrey Gryazev The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAM Rose Cinemas and BAMcinématek. Brooklyn, NY/May 10, 2013—From Friday, May 31 through Thursday, June 13, BAMcinématek presents a two-week run of Russian master Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia in a new 35mm print for its 30th anniversary, alongside Russian Cinema Now, a series showcasing contemporary films with special guests and Q&As. Both programs are part of TransCultural Express: American and Russian Arts Today, a collaborative venture to promote cultural exchange and the Mikhail Prokhorov Fund’s inaugural artistic alliance with a US performing arts institution. For more information on TransCultural Express, download the program press release. A metaphysical exploration of spiritual isolation and Russian identity, Tarkovsky’s (Solaris, Stalker) penultimate film Nostalghia (1983) follows Russian expat and misanthropic poet Andrei (Oleg Yankovsky, The Mirror) as he travels to Italy to conduct research on an 18th-century composer. In the course of his study, he is overcome by melancholy and a longing for his home country—a sentiment reflective of the exiled Tarkovsky’s own struggle with displacement, this being his first film made outside of the USSR (the film’s Italian title translates as “homesickness”). -

9781474437257 Refocus The

ReFocus: The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky 66616_Toymentsev.indd616_Toymentsev.indd i 112/01/212/01/21 111:211:21 AAMM ReFocus: The International Directors Series Series Editors: Robert Singer, Stefanie Van de Peer, and Gary D. Rhodes Board of advisors: Lizelle Bisschoff (University of Glasgow) Stephanie Hemelryck Donald (University of Lincoln) Anna Misiak (Falmouth University) Des O’Rawe (Queen’s University Belfast) ReFocus is a series of contemporary methodological and theoretical approaches to the interdisciplinary analyses and interpretations of international film directors, from the celebrated to the ignored, in direct relationship to their respective culture—its myths, values, and historical precepts—and the broader parameters of international film history and theory. The series provides a forum for introducing a broad spectrum of directors, working in and establishing movements, trends, cycles, and genres including those historical, currently popular, or emergent, and in need of critical assessment or reassessment. It ignores no director who created a historical space—either in or outside of the studio system—beginning with the origins of cinema and up to the present. ReFocus brings these film directors to a new audience of scholars and general readers of Film Studies. Titles in the series include: ReFocus: The Films of Susanne Bier Edited by Missy Molloy, Mimi Nielsen, and Meryl Shriver-Rice ReFocus: The Films of Francis Veber Keith Corson ReFocus: The Films of Jia Zhangke Maureen Turim and Ying Xiao ReFocus: The Films of Xavier Dolan -

Tarkovsky Is for Me the Greatest, the One Who Invented a New Language, True to the Nature of Film As It Captures Life As a Reflection, Life As a Dream.”

stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press stop press Curzon Mayfair 38 Curzon Street 7 – 13 DECEMBER London W1J Features £10/£8 Curzon Members; www.curzoncinemas.com Documentaries £6.50 Box Office: 0871 7033 989 TARKOVSKY FESTIVAL – A RETROSPECTIVE As part of the celebration of the 75th Anniversary of one of the undisputed masters of world cinema, Andrei Tarkovsky (1932 – 1986), Curzon Cinemas and Artificial Eye present screenings of his feature films, documentaries about him, and the reading of a stage play related to his work. Most screenings will be introduced by an actor or member of the crew, followed by a Q&A. Related activities will take place across the capital. “Tarkovsky is for me the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.” Ingmar Bergman FRI 7 DECEMBER 7PM OPENING GALA PLUS Q&A: THE SACRIFICE (PG) – NEW PRINT Director: Andrei Tarkovsky / Starring: Erland Josephson, Susan Fleetwood, Gudrun Gisladottir / Russia 1986 / 148 mins / Russian with English subtitles Tarkovsky's final film unfolds in the hours before a nuclear holocaust. Alexander is celebrating his birthday when a crackly TV announcement warns of imminent nuclear catastrophe. Alexander makes a promise to God that he will sacrifice all he holds dear, if the disaster can be averted. The next day dawns and everything is restored to normality, but Alexander must now keep his vow. We hope to welcome on stage lead actress Gudrun Gisladottir, and Layla Alexander-Garrett, the interpreter on THE SACRIFICE. -

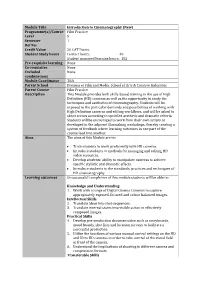

Module Title Introduction to Cinematography

Module Title Introduction to Cinematography (New) Programme(s)/Course Film Practice Level 5 Semester 1 Ref No: Credit Value 20 CAT Points Student Study hours Contact hours: 48 Student managed learning hours: 152 Pre-requisite learning None Co-requisites None Excluded None combinations Module Coordinator TBA Parent School Division of Film and Media, School of Arts & Creative Industries Parent Course Film Practice Description This Module provides both skills-based training in the use of High Definition (HD) cameras as well as the opportunity to study the techniques and aesthetics of cinematography. Students will be exposed to the particular demands and possibilities of working with High Definition cameras and editing workflows, and will be asked to shoot scenes according to specified aesthetic and dramatic criteria. Students will be encouraged to work from their own scripts as developed in the adjacent filmmaking workshops, thereby creating a system of feedback where learning outcomes in one part of the course feed into another. Aims The aims of this Module are to: Train students to work proficiently with HD cameras. Introduce students to methods for managing and editing HD video resources. Develop students’ ability to manipulate cameras to achieve specific stylistic and dramatic effects. Introduce students to the standards, practices and techniques of HD cinematography Learning outcomes On successful completion of this module students will be able to: Knowledge and Understanding 1. Work with a range of Digital Cinema Cameras to capture appropriately exposed, focused and colour balanced images. Intellectual Skills 2. Translate ideas into shot-sequences. 3. Translate internal states into visible action in effectively composed images. -

Paper VII, Philosophy and Film Semester V Aims: 1. to Acquaint

Paper VII, Philosophy and Film Semester V Aims: 1. To acquaint students with a new intriguing subject in Philosophy, i.e. Philosophy of Film. 2. To acquaint students with Film as an independent art form. 3. To acquaint students that the most powerful mass media of communication i.e. film has its pragmatic aspect and its own axiology. 4. To acquaint students with different aspects of Film philosophically. Unit I Ontology of Philosophy and Film Philosophy-in-Film, Philosophy-of-Film, Film Studies, Film Theories and Film Criticism Unit II Film Theories Auteur Theory, Marxist Film Theory, Feminist Film Theory, Formalist Film Theory and Screen Theory Unit III Philosophy Through Films Knowledge and Truth - Film Text: The Matrix; Problem of Identity - Film Text: Momento, Hindi Movies with themes of Duplicates; Ethics and Moral Responsibility - Film Text: Crimes and Misdemeanor, Social Political genre films; Philosophy of Religion - Film Text: The Rapture, Saint Films, Mythological films (Jai Santoshi Maa, Ramayan: The legend of Prince Ram, In the Name of the Rose); and Philosophy of Sci-Fiction Film – Film Text: Star Wars, Gravity Unit IV Praxis of Philosophy of Film 1 Film and Ethics – Film Text: Crime and Punishment, Deewar; Film and Psychoanalysis – Film Text: Psycho, Karthik Calling Karthik; Film and Society – Film Text: Corporate, Fashion, Page 3; Commercial vsArt Film – Mera Naam Joker, Anand; and Off-beat or Art Film – Film Text: Duvidha, Paar References: 1. Mary. M. Litch. Philosophy Through Film, 2002, New York : Routledge. 2. Paisly Livingstone and Carl Plantinga (ed) The Routledge Companion of Film and Philosophy. 2009 New York: Routledge 3. -

The Affirmative Aphasia of Tarkovsky's Mirror

„ Я [не] могу говорить”: The affirmative aphasia of Tarkovsky’s Mirror Emma Zofia Zachurski Mine is not a pleasant story, it does not possess the gentle harmony of invented tales; like the lives of all men who have given up trying to deceive themselves, it is a mixture of nonsense, madness and dreams… Taken from the opening of Hermann Hesse’s novel Demian: The Story of Emil Sinclair’s Youth (1919), Andrei Tarkovsky encounters this passage in 19821 and retroactively calls it the epigraph to his 1975 film Зеркало (Mirror). Hesse’s ‘mixture’ is only too relevant to the content of Mirror. Tarkovsky’s own return to the past refuses ‘gentle harmony’ as it unfolds in a non-linear assemblage of dreamlike mise-en- scène, stark historical documentary footage, lyrical readings of poetry by the filmmaker’s father Arseny Tarkovsky and a disorienting casting of actors and the filmmaker’s family members in multiple roles. However, neither the Hesse passage nor the Tarkovsky film are only interested in content. They both also share a sensitivity to form, to their language– the nonsense through which they make sense. In text this may be the nonsense of written language standing in for the sensations of the tactile, the aural and the visual that define the events of the past. Offering no more than paper and pen for these sensory experiences, text becomes ‘non-sense’ indeed. Tarkovsky, however, is not limited to text. He has access to the senses, his camera can directly record sound and vision. If Tarkovsky has access to the senses, though, does he also have access to sense? Tarkovsky offers a response: “In general, I view words as noise made by man”2. -

The Gospel According to Andrei: Biblical Narrative in the Films of Andrei Tarkovsky

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2020 The Gospel According to Andrei: Biblical Narrative in the Films of Andrei Tarkovsky Aurora J. Amidon Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020 Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Amidon, Aurora J., "The Gospel According to Andrei: Biblical Narrative in the Films of Andrei Tarkovsky" (2020). Senior Projects Spring 2020. 185. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020/185 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Amidon 1 The Gospel According to Andrei: Biblical Narrative in the Films of Andrei Tarkovsky Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Language and Literature and The Division of the Arts of Bard College by Aurora Amidon Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2020 Amidon 2 Acknowledgements To my parents, for raising me to value art over anything else--even if that meant showing me The Silence of the Lambs when I was nine. -

Tarkovsky's Legacy. Tarkovskian Inspirations in Contemporary Cinema

Marina Pellanda Tarkovsky’s legacy Tarkovskian inspirations in contemporary cinema THE STORY ACCORDING TO TARKOVSKY In his Répertoire, French writer Michel Butor imagined all men to be „continu- ously immersed like in a washtub“ in stories (Butor 1960, 1). Everything that is „other than us“, wrote the author, is known to us not because we have seen it but because someone has told us about it, with the configurations of meaning that make every narrated event something to communicate to others. In order to ex- ist, the story must allow itself first to be indiscriminately fragmented, and then forcibly reassembled. If we agree with Butor that narration seems to engulf us like water in a wash- tub, it is also true that every story remains essentially impossible to tell: as an in- tegral part of nature surrounding us, it is intolerant of any form of manipulation, since every manipulation is a meaningful organization of the awareness of time. Chained to the „present“ that is brought to life in every story, the imagination seems prevalently to be subject to a time that, along the lines of Schiller, we might define as „extraneous time“ (cfr. Morelli 1995, 13); nevertheless, it is often true that the user – be he a spectator or a reader – is allowed to proceed at an uneven pace through the event in which he is partaking, thereby tailoring the experi- ence to his own subjective needs. When this happens – for example in Sterne’s Tristram Shandy gentleman, or Joyce’s Ulysses or in the films of Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky who, while at the very back of a long shot and still out of focus, is slowly moving towards these pages – a standardization occurs that for some may be the emblem of an authentic waste of time, whereas for more insight- 549 Marina Pellanda ful eyes, it appears as a concession: the author grants the reader or spectator, the right to experience his own excursions through time.