Renaissanceternarysuspension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

Silent Music

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Philosophy Faculty Research Philosophy Department Fall 2010 Silent Music Andrew Kania Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/phil_faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Repository Citation Kania, A. (2010). Silent music. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68(4), 343-353. doi:10.1111/ j.1540-6245.2010.01429.x This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Silent Music Andrew Kania [This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Andrew Kania, “Silent Music” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68 (2010): 343-53, which has been published in final form at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540- 6245.2010.01429.x/abstract. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Please cite only the published version.] Abstract In this essay, I investigate musical silence. I first discuss how to integrate the concept of silence into a general theory or definition of music. I then consider the possibility of an entirely silent musical piece. I begin with John Cage’s 4′33″, since it is the most notorious candidate for a silent piece of music, even though it is not, in fact, silent. I conclude that it is not music either, but I argue that it is a piece of non-musical sound art, rather than simply a piece of theatre, as Stephen Davies has argued. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting Started

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/2/ Overview 2/3/ New features 2/4/ Understanding notation 2/5/ Technical support 3/ Use Guitar Pro 7 3/A/1/ Writing a score 3/A/2/ Tracks in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/3/ Bars in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/4/ Adding notes to your score. 3/A/5/ Insert invents 3/A/6/ Adding symbols 3/A/7/ Add lyrics 3/A/8/ Adding sections 3/A/9/ Cut, copy and paste options 3/A/10/ Using wizards 3/A/11/ Guitar Pro 7 Stylesheet 3/A/12/ Drums and percussions 3/B/ Work with a score 3/B/1/ Finding Guitar Pro files 3/B/2/ Navigating around the score 3/B/3/ Display settings. 3/B/4/ Audio settings 3/B/5/ Playback options 3/B/6/ Printing 3/B/7/ Files and tabs import 4/ Tools 4/1/ Chord diagrams 4/2/ Scales 4/3/ Virtual instruments 4/4/ Polyphonic tuner 4/5/ Metronome 4/6/ MIDI capture 4/7/ Line In 4/8 File protection 5/ mySongBook 1/ Introduction Welcome! You just purchased Guitar Pro 7, congratulations and welcome to the Guitar Pro family! Guitar Pro is back with its best version yet. Faster, stronger and modernised, Guitar Pro 7 offers you many new features. Whether you are a longtime Guitar Pro user or a new user you will find all the necessary information in this user guide to make the best out of Guitar Pro 7. 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/1/1 MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS macOS X 10.10 / Windows 7 (32 or 64-Bit) Dual-core CPU with 4 GB RAM 2 GB of free HD space 960x720 display OS-compatible audio hardware DVD-ROM drive or internet connection required to download the software 2/1/2/ Installation on Windows Installation from the Guitar Pro website: You can easily download Guitar Pro 7 from our website via this link: https://www.guitar-pro.com/en/index.php?pg=download Once the trial version downloaded, upgrade it to the full version by entering your licence number into your activation window. -

Book Two Sample

BOOK TWO BOOK TWO JB’s modern notation method for Guitar $19.99 ISBN 978-1-7336076-1-2 51999 9781733607612 BOOK TWO table of contents Introduction • Tuning The Guitar 3-4 • Four Finger Tips 4 Chapter 11) • Triplets 5 • C♯ on the A-String and B-String 6 • E♭ on the D-String and B-String 6 Chapter 12) • Time Signatures 10 • 6/8 Time Signature 11 Chapter 13) • Sixteenth Notes 14 • Counting Sixteenth Notes and Rests 15 • Clapping Exercises (First Set) 16 Chapter 14) • More Sixteenth Note Goodness 19 • Clapping Exercises (Second Set) 20 Chapter 15) • G♯ on the Low E-String, G-String, and High E-String 22 • A♭ on the Low E-String, G-String, and High E-String 23 Chapter 16) • D♯ on the D-String, and B-String 26 • D♭ on the A-String, and B-String 26 • Syncopation 27 Chapter 17) • Performance Marks; Tempo 32 • Dynamic 34 • Endings; Articulation & Expression 36 • Place Markers 38 Chapter 18) • Position Playing On The Board 40 • A♯ and G♭ ALL OVER THE BOARD 41 • Revisiting “Old Friends” 43-45 Chapter 19) • E♯ and C♭ Introduced 45 • Odd Time Signatures 46 • Cut-Time (2/2 Time Signature) 49 Chapter 20) • B♯ and F♭ Introduced 52 • More On Triplets 54 Appendix • Lead Sheets 59 • Chord Diagrams 60-62 1 Keep These Points In Mind: • For all of us, most keys we read are not in C Major. And thankfully, not in C# or C♭, as well. • Push and challenge yourself to be very accustomed to keys other than C Major. -

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Oranit Kongwattananon 1

Oranit Kongwattananon 1 Introduction Arvo Pärt, an Estonian composer, was born in 1935. He studied at Tallinn Conservatory under his composition teacher, Heino Eller, in 1958-1963. While studying, he worked as a sound engineer at the Estonian Radio, and continued working there until 1968, when he became a freelance composer. At the beginning of 1980, Arvo Pärt and his family emigrated to Austria where he received Austrian citizenship. Afterwards, he received a scholarship from Der Deutsche Akademische Austauschdienst (German Academic Exchange Service) in 1981-1982, so he and his family moved to West Berlin.1 Most of the works at the beginning of his career as a composer were for piano in neo- classical style. He won the first prize of the All-Union Young Composers’ Competition in Moscow in 1962, and turned his interest to serial music at this time. He studied from books and scores, which were difficult to obtain in the Soviet Union. The first work to which he applied serial techniques, Nekrolog, was composed in 1960. Although he was panned by the critics for this work, he nevertheless continued creating his works with serial techniques throughout the 1960s. One well-known piece called Credo, composed in 1968, was the last work combining tonal and atonal styles.2 For several years afterwards, Pärt turned his attention to studying tonal monody and two-part counterpoint exercises.3 Between 1968-1976 Pärt initiated a “self-imposed silence”; during which he published only one work, Symphony no. 3, whilst studing early music: At the beginning of this period, Pärt heard Gregorian chant for the first time in his life and was completely overwhelmed by what he heard: he immediately sought out other examples, and went on to make an intensive study of early music, including not only Gregorian chant, but also the music of the Notre Dame school, Gillaume de Machaut, 1 Wright, Stephen, “Arvo Pärt (1935- ),” in Music of the twentieth-century avant-garde: a biocritical sourcebook, ed. -

Presentation

Over 1200 Symbols More Beautiful than Ever SMuFL Compliant Advanced Support in Finale, Dorico, Sibelius & LilyPond Presentation © Robert Piéchaud 2016 v. 2.1.0 published by www.klemm-music.de — November 2 Presentation — Summary Foreword 3 November 2.1 Character Map 4 Clefs 5 Noteheads & Individual Notes 12 Noteflags 38 Rests 42 Accidentals (standard) 46 Microtonal & Non-Standard Accidentals 50 Articulations 63 Instrument Techniques 72 Fermatas & Breath Marks 105 Dynamics 110 Ornaments & Arpeggios 115 Repeated Lines & Other “Wiggles” 126 Octaves 132 Time Signatures & Other Numbers 134 Tempo Marking Items 141 Medieval Notation 145 Miscellaneous Symbols 150 Score Examples 163 Renaissance 163 Baroque 164 Bach 165 Early XXth Century 166 Ravel 167 XXIst Century 168 Requirements & Installation 169 Finale 169 Dorico 169 Sibelius 169 LilyPond 170 Free Technical Assistance 171 About the Designer 172 Credits 172 2 — November 2 Presentation — Foreword Welcome to November 2! November has been praised for years by musicians, publishers and engravers as one of the finest and most vivid fonts ever designed for music notation programs. For use in programs such as Finale, Dorico, Sibelius or LilyPond, November 2 now includes a astonishing variety of symbols, from usual shapes such as noteheads, clefs and rests to rarer characters like microtonal accidentals, special instrument techniques, early clefs or orna- ments, ranging from the Renaissance1 to today’s avant-garde music. Based on the principle that each detail means as much as the whole, crafted with ultimate care, November 2 is a font of unequalled coherence. While in tune with the most recent technologies, its inspiration comes from the art of tradi- tional music engraving. -

Standard Music Font Layout

SMuFL Standard Music Font Layout Version 1.0 (2014-06-16) Copyright © 2013–2014 Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH Acknowledgements This document reproduces glyphs from the Bravura font, copyright © Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH. Bravura is released under the SIL Open Font License and can be downloaded from http://www.smufl.org/fonts This document also reproduces some glyphs from the Unicode 6.2 code chart for the Musical Symbols range (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1D100.pdf). These glyphs are the copyright of their respective copyright holders, listed on the Unicode Consortium web site here: http://www.unicode.org/charts/fonts.html 2 Version history Version 0.1 (2013-01-31) . Initial version. Version 0.2 (2013-02-08) . Added tick barline. Changed names of time signature, tuplet and figured bass digit glyphs to ensure that they are unique. Add upside-down and reversed G, F and C clefs for cancrizans and inverted canons. Added Time signature + and Time signature fraction slash glyphs. Added Black diamond notehead, White diamond notehead, Half-filled diamond notehead, Black circled notehead, White circled notehead glyphs. Added 256th and 512th note glyphs. All symbols shown on combining stems now also exist as separate symbols. Added reversed sharp, natural, double flat and inverted flat and double flat glyphs for cancrizans and inverted canons. Added trill wiggle segment, glissando wiggle segment and arpeggiato wiggle segment glyphs. Added string Half-harmonic, Overpressure down bow and Overpressure up bow glyphs. Added Breath mark glyph. Added angled beater pictograms for xylophone, timpani and yarn beaters. Added alternative glyph for Half-open, per Weinberg. -

A New Look at Ars Subtilior Notation and Style in the Codex Chantilly, Ms. 564

A New Look at Ars Subtilior Notation and Style in the Codex Chantilly, Ms. 564 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Music Michael C. Evans March 2011 © 2011 Michael C. Evans. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled A New Look at Ars Subtilior Notation and Style in the Codex Chantilly, Ms. 564 by MICHAEL C. EVANS has been approved for the School of Music and the College of Fine Arts by Richard D. Wetzel Professor of Music History and Literature Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT EVANS, MICHAEL C., M.M., March 2011, Music History and Literature A New Look At Ars Subtilior Notation and Style in the Codex Chantilly, Ms. 564 Director of Thesis: Richard D. Wetzel The ars subtilior is a medieval style period marked with a high amount of experimentation and complexity, lying in between the apex of the ars nova and the newer styles of music practiced by the English and the Burgundians in the early fifteenth century. In scholarly accounts summarizing the period, however, musicologists and scholars differ, often greatly, on the precise details that comprise the style. In this thesis, I will take a closer look at the music of the period, with special relevance to the Codex Chantilly (F-CH-564), the main source of music in the ars subtilior style. In doing so, I will create a more exact definition of the style and its characteristics, using more precise language. -

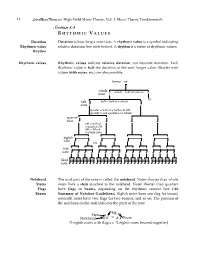

Rhythmic Values (Learnmusictheory.Net)

14 LearnMusicTheory.net High-Yield Music Theory, Vol. 1: Music Theory Fundamentals Section 1.4 R H Y T H M I C V ALUES Duration Duration is how long a note lasts. A rhythmic value is a symbol indicating Rhythmic value relative duration (see table below). A rhythm is a series of rhythmic values. Rhythm Rhythmic values Rhythmic values indicate relative duration, not absolute duration. Each rhythmic value is half the duration of the next longer value. Shorter note values (64th notes, etc.) are also possible. breve W whole whole = half of a breve note w w etc. half half = half of a whole note ˙ ˙ quarter = half of a half note OR quarter = one quarter of a whole quarter note œ 8th = half of œ œ œ a quarter OR 8th = 8th of a whole note eighth note œ œ etc. œ œ œ œ œ œ 16th note œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ 32nd note œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ Notehead The oval part of the note is called the notehead. Notes shorter than whole Stems notes have a stem attached to the notehead. Notes shorter than quarters Flags have flags or beams, depending on the rhythmic context (see 1.10 Beams Summary of Notation Guidelines). Eighth notes have one flag (or beam), sixteenth notes have two flags (or two beams), and so on. -

HORIZONTAL STRUCTURE One Way in Which Most Styles of Music Strive

CHAPTER XI HORIZONTAL STRUCTURE One way in which most styles of music strive to satisfy the listener is to present repeating patterns which are easily recognized by the listener. Certainly this represents a connection between music and mathematics, although the mathematics involved here is not deep for the mostpart. Duration of Notes Time durations in music are often measured in beats, which are the temporal units by which music is notated. Frequently one beat represents the time interval by which one is prone to “count off” the passing of time while the music is performed, although this is not always the case. The most basic notational unit, of course, is the note, and the duration of the note is indicated by such things as note stems, dots, and tuplet designations. The durational names of notes in Western music is based on the whole note, which has a duration in beats (often four) dictated by the time signature (discussed below). Notes whose duration has proportion 1/2n,n∈ Z+ with the duration of the whole note are named according to that proportion. Thus, if the whole note has a certain duration in beats, then the half note has half that duration, the quarternotehas one fourth that duration, etc. In the situation where a whole note gets four beats, then a half note gets two beats and the sixty-fourth note represents one eighth of a beat. We will use the term durational note to mean a note distinguished by its duration, such as half note, quarter note, independent of its associated pitch.